Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Soyuz

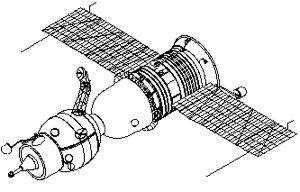

Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

The fundamental concept of the design can easily be summarized as obtaining minimum overall vehicle mass for the mission. This is accomplished by minimizing the mass of the re-entry vehicle. There were two major design elements to achieve this:

- Put all systems and space not necessary for re-entry and recovery outside of the re-entry vehicle, into a separate jettisonable 'living section', joined to the re-entry vehicle by a hatch. Every gram saved in this way saves two or more grams in overall spacecraft mass - for it does not need to be protected by heat shields, supported by parachutes, or braked on landing.

- Use a re-entry vehicle of the highest possible volumetric efficiency (internal volume divided by hull area). Theoretically this would be a sphere. But re-entry from lunar distances required that the capsule be able to bank a little, to generate lift and 'fly' a bit. This was needed to reduce the G forces on the crew to tolerable levels. Such a maneuver is impossible with a spherical capsule. After considerable study, the optimum shape was found to be the Soyuz 'headlight' shape - a hemispherical forward area joined by a barely angled cone (7 degrees) to a classic spherical section heat shield.

This design concept meant splitting the living area into two modules - the re-entry vehicle, with just enough space, equipment, and supplies to sustain the crew during re-entry; and a living module. As a bonus the living module provided an airlock for exit into space and a mounting area for rendezvous electronics.

The end result of this design approach was remarkable. The Apollo capsule designed by NASA had a mass of 5,000 kg and provided the crew with six cubic meters of living space. A service module, providing propulsion, electricity, radio, and other equipment would add at least 1,800 kg to this mass for the circumlunar mission. The Soyuz spacecraft for the same mission provided the same crew with 9 cubic meters of living space, an airlock, and the service module for the mass of the Apollo capsule alone!

The modular concept was also inherently adaptable. By changing the fuel load in the service module, and the type of equipment in the living module, a wide variety of missions could be performed. The superiority of this approach is clear to see: the Soyuz will remains in use at least 70 years later, while the Apollo was quickly abandoned. After studying a range of designs, the Chinese elected to copy the Soyuz layout for their Shenzhou spacecraft, rather than Apollo. Perversely, NASA copied the Apollo spacecraft layout for their Orion CEV, set to replace the shuttle after 2015. The Orion was in turn delayed. If Orion ever flies, will Soyuz still be flying when Orion is retired?

Origin

In the Soviet Union, manned spacecraft design in the late 1950's was solely handled by engineers within Sergei Korolev's design bureau. Korolev had designed the Vostok manned spacecraft that gave Russia the lead in the space race in the first half of the 1960's. Studies for a follow-on to Vostok, with the objective of sending a manned capsule on a circumlunar flight, began in 1959 under Tikhonravov. At this point it was assumed that any such flight would require use of launch vehicles derived from Korolev's R-7 ICBM. Since planned derivatives of the R-7 could not put more than six metric tons into orbit, it was immediately obvious that a circumlunar spacecraft would have to be assembled in low earth orbit from several R-7 launches. Therefore it would be necessary to perfect techniques for rendezvous, docking, and refueling of rocket stages in orbit. By 1960 to 1961 the studies, now dubbed 'L1', were expanded to cover automatic rendezvous and docking of several stages, and use of manipulators to assemble the stages.

Meanwhile the configuration of the re-entry vehicle for a Vostok follow-on was being investigated by other departments of Korolev's bureau. Lead for work on the re-entry problem was OKB-1's Gas Dynamics Department. There was no shortage of ideas. In 1959 Chief Designer Tsybin and Solovyev of the Spacecraft Department both offered designs for a winged manned spacecraft with a hypersonic lift-to-drag ratio of over 1.0. Prugnikov of the Warhead Department and Feoktistov of the Spacecraft Department proposed development of a ballistic capsule composed of variations of 'segmented spheres'. Korolev requested TsAGI, the state's Central Aerodynamic/Hydrodynamic Institute, to investigate all possible configurations. In a letter from A I Makarevskiy to Korolev on 9 September 1959 TsAGI set out its study plan. Aerodynamic characteristics at various angles of attack for a wide range of winged, spherical, elliptical, sphere-with cones, and conical shapes were to be analyzed at velocities from Mach 0.3 to Mach 25. The ballistic vehicle was to have a basic diameter of 2.5 m, a total internal volume of 3 to 3.5 cubic meters, and a living volume of 2 to 3 cubic meters. Separately considered for all configurations were aerodynamics of ejection seats or capsules with a diameter of 0.9 cubic meters and a length of 1.85 meters. Most of the work was promised for completion by the end of 1959. To exploit this database, Reshetin started a project group to conduct trade-off studies of the various configurations at the beginning of 1960. It was upgraded to a project sector, under the leadership of Timchenko, in 1961.

The 1960 studies considered various configurations of ballistic capsule, wing-canard schemes of conventional aircraft layout, and tailless hybrid configurations. As was done at General Electric, each configuration had a complete theoretical study, from the standpoint of aerodynamics, trajectories, resulting spacecraft masses, thermal protection requirements, and so on. By the end of 1960 it was found that the winged designs were too heavy for launch by the R-7 and in any case presented difficult re-entry heating problems that were beyond the existing technology. Studies of re-entry trajectories from lunar distances showed that a modest lift-to-drag ratio of 0.2 would be sufficient to lower G forces and allow the capsule to fly 3,000 to 7,000 km from its re-entry point and land on the Soviet territory. When the existing guidance accuracy were taken into account, this was increased to 0.3 to allow sufficient maneuverability to ensure the capsule could land within 50 km of the aim point.

These studies were the most complex ever undertaken, and Korolev obtained assistance from the most brilliant Soviet aerodynamicists, notably Likhushin at NII-1, and those refugees from Chelomei's take-over of their bureaus, Myasishchyev at TsAGI, and Tsybin at NII-88. In 1962 the classic Soyuz 'headlight' configuration was selected: a hemispherical forebody transition in a barely conical (7 degree) section to the section-of-a-sphere heat shield.

The Gas Dynamics Department had conceived of the modular scheme to reduce the mass of the re-entry vehicle in 1960. The Spacecraft Department's competing design was two modules, like Apollo. Further iterative studies in 1961 to 1962 reached the conclusion that the Soyuz should consist of four sections. From fore to aft these were the living module; the landing module; the equipment-propulsion module; and an aft jettisonable module, that would contain the electronics for earth orbit rendezvous (this was to be jettisoned after the last docking was completed and before translunar injection. Until the 1990's this compartment on the early Soyuz models was misidentified as a 'toroidal fuel tank' by Western space experts).

This configuration was selected only after considerable engineering angst. From the point of view of pulling the capsule away from the rocket in an emergency, positioning the capsule at the top of the spacecraft was ideal. But to use this layout with the living module concept, a hatch would have to be put through the heat shield to connect the two living areas. Korolev's engineers just could not accept the idea of violating the integrity of the shield (and would later get in bitter battles with other design bureaus when competing manned spacecraft - Kozlov's Soyuz VI and Chelomei's TKS - used such hatches).

Allegations have been made that the Korolev Soyuz design was based on General Electric's losing Apollo proposal. However study of the chronology of the two projects shows that early development work was almost simultaneous. Independently of General Electric, Korolev had arrived at the modular spacecraft approach and a similar capsule concept before the General Electric proposal was published. However there was plenty of time to incorporate detailed features of the General Electric design into Soyuz before it was finalized.

On May 7, 1963 Korolev signed the final draft project for Soyuz. The baseline consisted of a circumlunar Soyuz A (7K) manned spacecraft. This would be boosted around the moon by the Soyuz B (9K) rocket stage, which was fueled by the Soyuz V (11K) tanker. However Korolev understood very well that financing for a project of this scale would only be forthcoming from the Ministry of Defense. Therefore his draft project proposed two additional modifications of the Soyuz 7K: the Soyuz-P (Perekhvatchik, Interceptor) space interceptor and the Soyuz-R (Razvedki, intelligence) command-reconnaissance spacecraft. The Soyuz-P would use the Soyuz B rocket motor to boost it to intercepts in orbits of up to 6,000 km.

The Soyuz draft project was submitted to the expert commission on 20 March 1963. However only the reconnaissance and interceptor applications of the Soyuz could be understood and supported by the VVS air force and RVSN rocket forces. Korolev wanted to concentrate on the manned space exploration mission and felt he had no time to work on a Soyuz military 'side-line'. In 1963 his OKB-1 was working on the three-crew 3KV Voskhod, the two-crew 3KD Voskhod-2, the immense N1 11A52 launch vehicle , its smaller derivatives 11A53 (N11) and 11A54 (N111), and a large number of other unmanned spacecraft. Therefore it was decided that OKB-1 would concentrate only on development of the 7K spacecraft, while development of the 9K and 11K spacecraft would be passed to other design bureaus. The military projects Soyuz-P and Soyuz-R were ‘subcontracted' to OKB-1 Filial number 3, based in Samara.

To Korolev's frustration, while Filial 3 received budget to develop the military Soyuz versions, his own Soyuz-A did not receive adequate financial support. The 7K-9K-11K plan would have required five successful automatic dockings to succeed. This seemed impossible at the time. Instead the road to the moon advocated by Vladimir Nikolayevich Chelomei was preferred. Chelomei was Korolev's arch-rival, and had the advantage of having Nikita Khrushchev's son in his employ. He attempted to break the stranglehold that ‘Korolev and Co.', also known as the ‘Podpilki' Mafia, had on the space program. Chelomei's LK-1 single-manned spacecraft, to be placed on a translunar trajectory in a single launch of his UR-500K rocket, was the preferred approach. Chelomei issued the advanced project LK-1 on 3 August 1964, the same day the historic decree was issued that set forth the Soviet plan to beat the Americans to the moon. Under this decree Chelomei was to develop the LK-1 for the manned lunar flyby while Korolev was to develop the N1-L3 for the manned lunar landing. The 7K-9K-11K system was canceled. But the Soyuz A itself would be developed by Korolev as the 7K-OK manned earth orbit spacecraft. Korolev kept his options open and had versions of it designed which would in the end be flown for manned orbital (7K-LOK) and circumlunar (7K-L1) missions.

The Soyuz spacecraft was initially designed for rendezvous and docking operations in near earth orbit, leading to piloted circumlunar flight. In the definitive December 1962 Soyuz draft project, the Soyuz-A appeared as a two-place spacecraft. The Soyuz would have been launched on a lunar flyby after successive launches of 11K tanker spacecraft with a 9K translunar injection stage.

To Korolev's frustration, while Filial 3 received budget to develop the military Soyuz versions, his own Soyuz-A did not receive the support of the leadership for inclusion in the space program of the USSR. The 7K-9K-11K plan would have required five successful automatic dockings to succeed. This seemed impossible at the time. Instead Chelomei's LK-1 single-manned spacecraft, to be placed on a translunar trajectory in a single launch of his UR-500K rocket, was the preferred approach. According to the historic decree of 3 August 1964 that set forth the Soviet plan to beat the Americans to the moon, Chelomei was to develop the LK-1 for the manned lunar flyby while Korolev was to develop the N1-L3 for the manned lunar landing. The Soyuz-A was cancelled.

In the second quarter of 1963, when Korolev had begun design of the Voskhod multi-manned spacecraft, he instructed his bureau to begin design of a three-manned orbital version of the Soyuz A, the 7K-OK. But the crush of work on other projects and the new lunar landing project resulted in development of the 7K-OK being stopped by the fall of 1964. Soyuz was pushed into the background.

On 14 October 1964 Khrushchev was ousted from power, and Chelomei lost his patron. Soon thereafter, Korolev quietly reanimated his Soyuz-A project - not the circumlunar version, but a 7K-OK orbital spacecraft. Korolev's stated plan was for two of these spacecraft to demonstrate rendezvous and docking in earth orbit - but this was really a cover in preparation for wresting the circumlunar program back from Chelomei.

On 25 October 1965, less than three months before his death, Korolev regained the project for manned circumlunar flight. This would use a derivative of the 7K-OK, the 7K-L1, launched by Chelomei's UR-500K, but with a Block D translunar injection stage from the N1. Originally Korolev considered that the 7K-L1, for either safety or mass reasons, could not be boosted directly by the UR-500K toward the moon. He envisioned launch of the unmanned 7K-L1 into low earth orbit, followed by launch and docking of a 7K-OK with the 7K-L1. The crew would then transfer to the L1, which would then be boosted toward the moon. This was his hidden reason for the development of the 7K-OK.

On the first orbital launch of the 7K-OK in November 1966 a large number of failures occurred, indicating many errors in construction. The spacecraft was uncontrollable and was finally destroyed by the on-board APO destruct system.

On the second launch attempt on 14 December, the Soyuz incorrectly detected a failure of the launch vehicle at 27 minutes after an aborted launch attempt. The launch escape system activated while the vehicle was still fuelled on the pad, pulling the capsule away from the vehicle but exploding the launch vehicle and killing and injuring several people. Analysis of the failure indicated numerous problems in the escape system.

The 7K-OK, after sinking to the bottom of the Aral Sea after a trouble-ridden third flight, was taken into space by cosmonaut Komarov in April 1967. This disastrous flight ended in the cosmonaut being killed when the parachute failed to deploy. The 7K-OK parachute system was redesigned to the extent possible given the constraints of the moon race and went on to accomplish 13 relatively successful manned and unmanned earth orbital flights. After the Soviets lost the moon race, a plan to beat the Americans in the space station race was conceived. The 7K-OK was modified to the space station ferry configuration 7K-OKS with the addition of a docking tunnel. This configuration killed three cosmonauts aboard Soyuz 11 in 1971. Thereafter the spacecraft underwent a complete redesign, resulting in the substantially safer 7K-T, which flew dozens of times to Salyut and Almaz space stations until replaced by the Soyuz T in 1981. This was later replaced by the Soyuz TM and TMA models for the Mir and ISS stations, mainly involving electronics upgrades. These provided the only American/European/Russian access to space after the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011.

| Sever Russian manned spacecraft. Study 1959. Sever was the original OKB-1 design for a manned spacecraft to replace the Vostok. It was designed to tackle such problems as maneuvering in orbit, rendezvous and docking, and testing of lifting re-entry vehicles. |

| L1-1960 Russian manned lunar flyby spacecraft. Study 1960. Circumlunar manned spacecraft proposed by Korolev in January 1960. The L1 would a man on a loop around the moon and back to earth by 1964. |

| L4-1960 Russian manned lunar orbiter. Study 1960. Lunar orbiter proposed by Korolev in January 1960. The spacecraft was to take 2 to 3 men to lunar orbit and back to earth by 1965. |

| Soyuz A Russian manned spacecraft. Study 1962. The 7K Soyuz spacecraft was initially designed for rendezvous and docking operations in near earth orbit, leading to piloted circumlunar flight. |

| Soyuz B Russian space tug. Study 1962. In the definitive December 1962 Soyuz draft project, the Soyuz B (9K) rocket acceleration block would be launched into a 225 km orbit by a Soyuz 11A511 booster. |

| Soyuz V Russian logistics spacecraft. Cancelled 1964. In the definitive December 1962 Soyuz draft project, the Soyuz B (9K) rocket acceleration block would be launched into a 225 km orbit by a Soyuz 11A511 booster. |

| L1-1962 Russian manned lunar flyby spacecraft. Study 1962. Early design that would lead to Soyuz. A Vostok-Zh manned tug would assemble rocket stages in orbit. It would then return, and a Soyuz L1 would dock with the rocket stack and be propelled toward the moon. |

| Soyuz P Russian manned combat spacecraft. Study 1963. In December 1962 Sergei Korolev released his draft project for a versatile manned spacecraft to follow Vostok. The Soyuz A was primarily designed for manned circumlunar flight. |

| Soyuz R Russian manned spacecraft. Cancelled 1966. A military reconnaissance version of Soyuz, developed by Kozlov at Samara from 1963-1966. It was to consist of an the 11F71 small orbital station and the 11F72 Soyuz 7K-TK manned ferry. |

| Soyuz A SA Russian manned spacecraft module. Study 1962. Original Soyuz design, allowing crew of three without spacesuits. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz A BO Russian manned spacecraft module. Study 1962. Original design with notional docking system with no probe and internal transfer tunnel. Living section. |

| Soyuz A PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. Study 1962. Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system but with no base flange for a shroud. Equipment-engine section. |

| L3-1963 Russian manned lunar lander. Study 1963. Korolev's original design for a manned lunar landing spacecraft was described in September 1963 and was designed to make a direct lunar landing using the earth orbit rendezvous method. |

| L4-1963 Russian manned lunar orbiter. Study 1963. The L-4 Manned Lunar Orbiter Research Spacecraft would have taken two to three cosmonauts into lunar orbit for an extended survey and mapping mission. |

| Soyuz 7K-TK Russian manned spacecraft. Cancelled 1966. To deliver crews to the Soyuz R 11F71 station Kozlov developed the transport spacecraft 11F72 Soyuz 7K-TK. |

| Soyuz PPK Russian manned combat spacecraft. Study 1964. The Soyuz 7K-PPK (pilotiruemiy korabl-perekhvatchik, manned interceptor spacecraft) was a revised version of the Soyuz P manned satellite inspection spacecraft. |

| Soyuz VI Russian manned combat spacecraft. Cancelled 1965. To determine the usefulness of manned military space flight, two projects were pursued in the second half of the 1960's. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Tether Russian manned spacecraft. Study 1965. Korolev was always interested in application of artificial gravity for large space stations and interplanetary craft. He sought to test this in orbit from the early days of the Vostok program. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Russian manned spacecraft. Development of a three-manned orbital version of the Soyuz, the 7K-OK was approved in December 1963. Launched 1966 - 1969. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK (Soyuz 2, 5, passive) Null |

| Soyuz 7K-OK SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 17 launches, 1966.11.28 (Cosmos 133) to 1970.06.01 (Soyuz 9). Post-Soyuz 1 modification, allowing crew of three without spacesuits. Analogue sequencer and computers operate spacecraft. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 17 launches, 1966.11.28 (Cosmos 133) to 1970.06.01 (Soyuz 9). Heavy-duty male/female docking system with no internal transfer tunnel. Igla automatic rendezvous and docking system. Living section. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 17 launches, 1966.11.28 (Cosmos 133) to 1970.06.01 (Soyuz 9). Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK (Soyuz 9, non docking) Null |

| Soyuz 7K-L1 Russian manned lunar flyby spacecraft. The Soyuz 7K-L1, a modification of the Soyuz 7K-OK, was designed for manned circumlunar missions. Lunar flyby and return satellite, Russia. Launched 1967 - 1970. |

| Soyuz 7K-L1P Technology satellite, Russia. Launched 1967. |

| Soyuz OB-VI Russian manned space station. Cancelled 1970. In December 1967 OKB-1 chief designer Mishin managed to have Kozlov's Soyuz VI project killed. In its place he proposed to build a manned military station based on his own Soyuz 7K-OK design. |

| Soyuz 7K-L1 SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 12 launches, 1967.03.10 (Cosmos 146) to 1970.10.20 (Zond 8). Increased heat shield protection and presumably reaction control system propellant for re-entry from lunar distances. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz 7K-L1 SOK Russian manned spacecraft module. 12 launches, 1967.03.10 (Cosmos 146) to 1970.10.20 (Zond 8). Separates before trans-lunar injection. Jettisonable support cone. |

| Soyuz 7K-L1 PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 12 launches, 1967.03.10 (Cosmos 146) to 1970.10.20 (Zond 8). Modification of Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Aelita satellite Russian infrared astronomy satellite. Cancelled 1982. The Aelita infrared astronomical telescope spacecraft was derived from the Soyuz manned spacecraft and had an unusually long gestation. |

| Soyuz 7K-L1A Russian manned lunar orbiter. Hybrid spacecraft used in N1 launch tests. |

| Soyuz 7K-L1S Alternate designation for [Soyuz 7K-L1A] manned lunar orbiter. |

| Soyuz Kontakt Russian manned spacecraft. Cancelled 1974. Modification of the Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft to test in earth orbit the Kontakt rendezvous and docking system. |

| Soyuz 7K-OK (Soyuz 6, non docking, special) Null |

| LK Russian manned lunar lander. The LK ('Lunniy korabl' - lunar craft) was the Soviet lunar lander - the Russian counterpart of the American LM Lunar Module. Manned Lunar lander test satellite, Russia. Launched 1970 - 1971. |

| Soyuz 7KT-OK Russian manned spacecraft. This was a modification of Soyuz 7K-OK with a lightweight docking system and a crew transfer tunnel. Launched 1971. |

| Soyuz 7K-LOK Russian manned lunar orbiter. The two-crew LOK lunar orbiting spacecraft was the largest derivative of Soyuz developed. Manned Lunar orbit and return satellite, Russia. Launched 1972. |

| Soyuz 7K-LOK SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 2 launches, 1971.06.26 (N-1 6L) to 1972.11.23 (LOK). Increased heat shield protection and presumably reaction control system propellant for re-entry from lunar distances. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz 7K-OKS SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 2 launches, 1971.04.23 (Soyuz 10) to 1971.06.06 (Soyuz 11). Post-Soyuz 1 modification, allowing crew of three without spacesuits. Analogue sequencer and computers operate spacecraft. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz 7K-LOK BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 2 launches, 1971.06.26 (N-1 6L) to 1972.11.23 (LOK). Living section. |

| Soyuz 7K-OKS BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 2 launches, 1971.04.23 (Soyuz 10) to 1971.06.06 (Soyuz 11). Lightweight male/female docking system with roller-type probe, internal transfer tunnel. Living section. |

| Soyuz 7K-OKS PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 2 launches, 1971.04.23 (Soyuz 10) to 1971.06.06 (Soyuz 11). Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Soyuz 7K-T Russian manned spacecraft. Launched 1972 - 1981. |

| Soyuz 7K-T SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 23 launches, 1972.06.26 (Cosmos 496) to 1981.05.14 (Soyuz 40). Post-Soyuz 11 modification for crew of two in spacesuits. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz 7K-T BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 23 launches, 1972.06.26 (Cosmos 496) to 1981.05.14 (Soyuz 40). Lightweight male/female docking system with roller-type probe, internal transfer tunnel (Collar Length: 0.22 m. Probe Length: 0. Living section. |

| Soyuz 7K-T PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 23 launches, 1972.06.26 (Cosmos 496) to 1981.05.14 (Soyuz 40). Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Soyuz 7K-T/AF (Soyuz 13) Null |

| Soyuz 7K-TM Russian manned spacecraft. The Soyuz 7K-T as modified for the docking with Apollo. Launched 1974 - 1975. |

| Soyuz 7K-T/A9 Russian manned spacecraft. Version of 7K-T for flights to Almaz. Known difference with the basic 7K-T included systems for remote control of the Almaz station and a revised parachute system. Russian orbital launch vehicle variant. |

| Soyuz 7K-S Russian manned spacecraft. The Soyuz 7K-S had its genesis in military Soyuz designs of the 1960's. Launched 1974 - 1976. |

| Soyuz ASTP SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 4 launches, 1974.04.03 (Cosmos 638) to 1975.07.15 (Soyuz 19 (ASTP)). Post-Soyuz 11 modification for crew of two in spacesuits. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz ASTP BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 4 launches, 1974.04.03 (Cosmos 638) to 1975.07.15 (Soyuz 19 (ASTP)). Universal docking system designed for ASTP with three petaled locating system and internal transfer tunnel. No automated rendezvous and docking system. Living section. |

| Soyuz ASTP PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 4 launches, 1974.04.03 (Cosmos 638) to 1975.07.15 (Soyuz 19 (ASTP)). Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Soyuz 7K-MF6 Russian manned spacecraft. Soyuz 22. Soyuz 7K-T modified with installation of East German MF6 multispectral camera. Used for a unique solo Soyuz earth resources mission. Launched 1976. |

| Soyuz 7K-MF6 SA Russian manned spacecraft module. One launch, 1976.09.15, Soyuz 22. Post-Soyuz 11 modification for crew of two in spacesuits. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz 7K-MF6 BO Russian manned spacecraft module. One launch, 1976.09.15, Soyuz 22. MKF6 Camera replaced docking system and Igla automatic rendezvous and docking system deleted. Four windows, BO separated after retrofire. Living section. |

| Soyuz 7K-MF6 PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. One launch, 1976.09.15, Soyuz 22. Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Progress Russian logistics spacecraft. Progress took the basic Soyuz 7K-T manned ferry designed for the Salyut space station and modified it for unmanned space station resupply. Cargo satellite operated by RKK, Russia. Launched 1978 - 1990. |

| Soyuz T Russian manned spacecraft. Soyuz T had a long gestation, beginning as the Soyuz VI military orbital complex Soyuz in 1967. Launched 1978 - 1986. |

| Progress OKD Russian manned spacecraft module. 43 launches, 1978.01.20 (Progress 1) to 1990.05.06 (Progress 42). Fuel module for refueling space stations. |

| Progress GO Russian manned spacecraft module. 43 launches, 1978.01.20 (Progress 1) to 1990.05.06 (Progress 42). Igla automatic rendezvous and docking system. Cargo section. |

| Progress PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 43 launches, 1978.01.20 (Progress 1) to 1990.05.06 (Progress 42). Derived from Soyuz 7K-OK basic PAO service module with pump-fed main engines and separate RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Soyuz T SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 18 launches, 1978.04.04 (Cosmos 1001) to 1986.03.13 (Soyuz T-15). Significantly improved Soyuz re-entry capsule, based on development done in Soyuz 7K-S program. Accommodation for crew of three in spacesuits. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz T BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 18 launches, 1978.04.04 (Cosmos 1001) to 1986.03.13 (Soyuz T-15). Lightweight male/female docking system with flange-type probe, internal transfer tunnel. Igla automatic rendezvous and docking system. Living section. |

| Soyuz T PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 18 launches, 1978.04.04 (Cosmos 1001) to 1986.03.13 (Soyuz T-15). Improved PAO service module derived from Soyuz 7K-S with pressure-fed main engines and unitary RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Soyuz TM Russian manned spacecraft. Launched 1986 - 2002. |

| Soyuz TM SA Russian manned spacecraft module. 34 launches, 1986.05.21 (Soyuz TM-1) to 2002.04.25 (Soyuz TM-34). Significantly improved Soyuz re-entry capsule, based on development done in Soyuz 7K-S program. Accommodation for crew of three in spacesuits. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz TM BO Russian manned spacecraft module. 34 launches, 1986.05.21 (Soyuz TM-1) to 2002.04.25 (Soyuz TM-34). Lightweight male/female docking system with flange-type probe, internal transfer tunnel. Kurs automatic rendezvous and docking system . Living section. |

| Soyuz TM PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. 34 launches, 1986.05.21 (Soyuz TM-1) to 2002.04.25 (Soyuz TM-34). Further improvement of Soyuz T PAO service module with pressure-fed main engines and unitary RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Progress M Russian logistics spacecraft. Progress M was an upgraded version of the original Progress. New service module and rendezvous and docking systems were adopted from Soyuz T. Cargo satellite operated by RKK > RAKA, Russia. Launched 1989 - 2009. |

| Progress M OKD Russian manned spacecraft module. Operational, first launch 1989.08.23 (Progress M-1). Fuel module for refueling space stations. |

| Progress M GO Russian manned spacecraft module. Operational, first launch 1989.08.23 (Progress M-1). Two Kurs-type rendezvous antennas. Cargo section. |

| Progress M PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. Operational, first launch 1989.08.23 (Progress M-1). Improved PAO service module derived from Soyuz 7K-S with pressure-fed main engines and unitary RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| Progress-M-VDU 14, 38 (11F615A55, 7KTGM) Null |

| Soyuz TM (APAS, Soyuz TM 16) Null |

| Progress M2 Russian logistics spacecraft. Cancelled 1993. As Phase 2 of the third generation Soviet space systems it was planned to use a more capable resupply craft for the Mir-2 space station. |

| Progress M VBK Russian manned spacecraft module. Two launched, 1993-1994. This payload return capsule was brought to the Mir space station aboard a Progress M freighter. It was loaded by the cosmonauts aboard the station, then reinstalled in the Progress M. Ballistic landing capsule - return of experimental materials from Mir space station. |

| Progress M1 Russian logistics spacecraft. Progress M1 was a modified version of the Progress M resupply spacecraft capable of delivering more propellant than the basic model to the ISS or Mir. Cargo satellite operated by RAKA, Russia. Launched 2000 - 2004. |

| Progress M-SO Russian docking and airlock module for the International Space Station. Delivered to the station by the Progress service module, which was jettisoned after docking. |

| Soyuz TMA Russian three-crew manned spacecraft. Designed for use as a lifeboat for the International Space Station. After the retirement of the US shuttle in 2011, Soyuz TMA was the only conveying crews to the ISS. Except for the Chinese Shenzhou, it became mankind's sole means of access to space. Launched 2002 - 2011. |

| Soyuz TMA SA Russian manned spacecraft module. Operational. First launch 2002.10.30. Reentry capsule. |

| Soyuz TMA BO Russian manned spacecraft module. Operational. First launch 2002.10.30. Lightweight male/female docking system with flange-type probe, internal transfer tunnel. Kurs automatic rendezvous and docking system with two Kurs antennae, no tower. Living section. |

| Soyuz TMA PAO Russian manned spacecraft module. Operational. First launch 2002.10.30. Further improvement of Soyuz T PAO service module with pressure-fed main engines and unitary RCS/main engine propellant feed system. Equipment-engine section. |

| DSE-Alpha Russian manned lunar flyby spacecraft. Study 2005. Potential commercial circumlunar manned flights were offered in 2005, using a modified Soyuz spacecraft docked to a Block DM upper stage. |

| Progress-M 1M - 29M (11F615A60, 7KTGM) Null |

| Soyuz TMA-M Manned spcecraft satellite, Russia. Launched 2010 - 2016. |

| Soyuz MS Russian three-crew manned spacecraft. Evolved from the Soyuz TMA incorporating numerous minor improvements identified over time. New digital computer, more redundancy in attitude control and docking systems, modernized electronics and solar power. Launched 2016 - on. |

| Progress MS Russian logistics spacecraft. Incorporated systems evolved from the Soyuz TMA. New digital computer, more redundancy in attitude control and docking systems, modernized electronics and solar power. Cargo satellite operated by RKK > RAKA, Russia. Launched 2015 - 2017. |

| Progress-M1 01M - 02M (11F615A70, 7KTGM) Null |

| Soyuz 7K-L3S Version of the Soyuz designed to be used in a combined lunar orbit / robot soil return mission to upstage the Americans prior to Apollo 11. |

| VBK-Raduga Reentry capsule which allowed returning materials from the space station Mir. They were launched and finally deorbited together with Progress-M cargo craft. |

People: Tsybin, Chelomei, Mishin, Mnatsakanian, Beregovoi, Komarov, Shatalov, Lazarev, Filipchenko, Nikolayev, Yazdovsky, Kolodin, Grechko, Khrunov, Gagarin, Yeliseyev, Gorbatko, Volynov, Kubasov, Sevastyanov, Shonin, Volkov. Country: Russia. Flights: Soyuz 1, Soyuz 2A, Soyuz s/n 3/4, Soyuz s/n 5/6, Soyuz s/n 7, Soyuz 3, Soyuz 4, Soyuz 4/5, Soyuz 5, Soyuz sn 14, Soyuz s/n 15+16, Soyuz 6, Soyuz 7, Soyuz 8, Soyuz 9. Launch Sites: Baikonur, Plesetsk. Agency: RVSN, MOM.

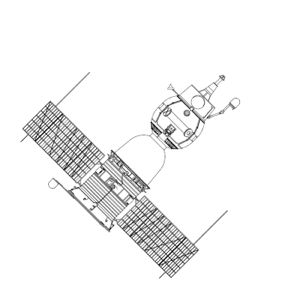

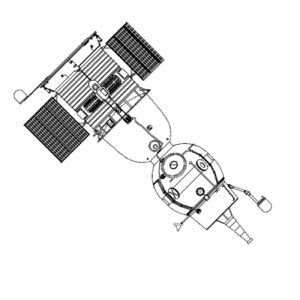

| Soyuz 4 and 5 Soyuz 4 and 5 in docked configuration Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz TM cabin Soyuz TM cabin during ascent Credit: RKK Energia |

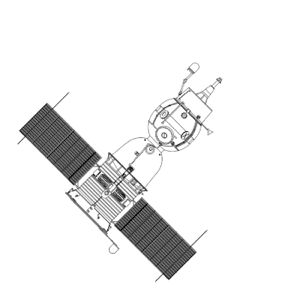

| Soyuz TM from space Credit: RKK Energia |

| Soyuz-MS 1 - 12 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

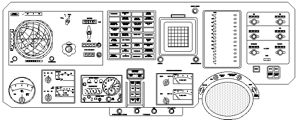

| Soyuz OM panel Detail of orbital module command panel of Soyuz OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

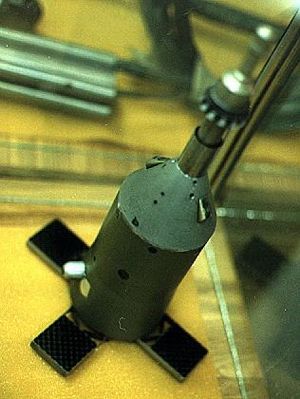

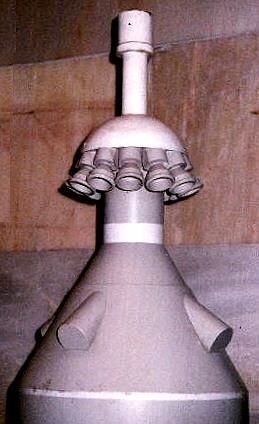

| Soyuz escape tower Soyuz launch escape system - air tunnel test model Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz OK panel Detail of left command panel of Soyuz OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Bottom Credit: © Mark Wade |

| LOK Descent Module LOK Descent Module and Orbital Module Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK probe Soyuz 7K-OK docking probe Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Panel Soyuz 7K-OK Control panel of the initial earth orbit version of Soyuz. Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Gas dynamic tunnel Gas dynamic tunnel tests Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Icon Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

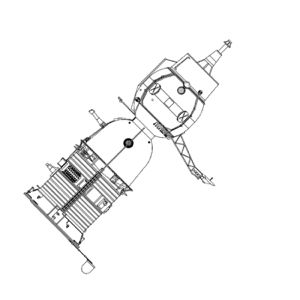

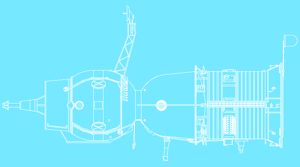

| Soyuz 7K-OK Side Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Top Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Icon Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz Icon Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Background Soyuz Background Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz orbital module Soyuz 7K-OKS passive docking orbital module Credit: Andy Salmon |

| Soyuz OPS Soyuz escape tower (as used on early Soyuz launches) Credit: Andy Salmon |

| Soyuz OM interior Interior view of Soyuz 4 orbital module (through open side hatch) Credit: Andy Salmon |

1959 March 1 - .

- OKB-1 preliminary work on circumlunar spacecraft - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Feoktistov.

Program: Lunar L1.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned space station. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Sever.

The first design sketched out was known as Sever (North). The reentry capsule had the same configuration as the ultimate Soyuz design but was 50% larger. By summer 1959 Feoktistov had reduced the size to that of the later Soyuz, while retaining the three-man crew size.

1961 April 10 - .

- Vostok preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Korolev,

Moskalenko,

Nelyubov,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Rudnev,

Titov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Sever.

Kamanin plays badminton with Gagarin, Titov, and Nelyubov, winning 16 to 5. At 12:00 a meeting is held with the cosmonauts at the Syr Darya River. Rudnev, Moskalenko, and Korolev informally discuss plans with Gagarin, Titov, Nelyubov, Popovich, Nikolayev, and Bykovsky. Korolev addresses the group, saying that it is only four years since the Soviet Union put the first satellite into orbit, and here they are about to put a man into space. The six cosmonauts here are all ready and qualified for the first flight. Although Gagarin has been selected for this flight, the others will follow soon - in this year production of ten Vostok spacecraft will be completed, and in future years it will be replaced by the two or three-place Sever spacecraft. The place of these cosmonauts here does not indicate the completion of our work, says Korolev, but rather the beginning of a long line of Soviet spacecraft. Korolev predicts that the flight will be completed safely, and he wishes Yuri Alekseyevich success. Kamanin and Moskalenko follow with their speeches. In the evening the final State Commission meeting is held. Launch is set for 12 April and the selection of Gagarin for the flight is ratified. The proceedings are recorded for posterity on film and tape.

1962 February 10 - .

- Sever spacecraft trials - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Voronin. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Sever. Two officers start a 15 day test aboard a mock-up of the Sever spacecraft, but without the participation of the IAKM. The whole thing was planned by Voronin's OKB in GKNII..

1962 February 13 - .

- Sever trial - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Bushuyev, Vershinin, Voronin, Yazdovskiy. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Sever. Vershinin, Bushuev and others are at OKB-124 for Voronin's Sever experiment. It was a bit mistake not to include IAKM in the 15-day experiment. This is Yazdovskiy's doing. He wanted to get a second source due to problems with IAKM's equipment.

1962 August 8 - .

- Additional Vostok missions; launch preparations. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gagarin,

Korolev,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Rudenko,

Titov.

Program: Vostok,

Soyuz.

Flight: Vostok 3,

Vostok 4,

Vostok 5,

Vostok 6,

Vostok 6A,

Vostok 7,

Vostok 8,

Vostok 9.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V,

Vostok.

Kamanin discusses with Rudenko the need for construction and flight of ten additional Vostok spacecraft. Korolev still plans to have the first Soyuz spacecraft completed and flying by May 1963, but Kamanin finds this completely unrealistic. The satellite is still only on paper; he doesn't believe it will fly until 1964. If the Vostoks are not built, Kamanin believes the Americans will surpass the Russians in manned spaceflight in 1963-1964. From 13:00 to 14:00 Nikolayev spends an hour in his spacesuit in the ejection seat. Kamanin finds many mistakes in the design of the ejection seat. There is no room for error in disconnect of the ECS, in release of the seat, and so on. At 17:00 the State Commission holds a rally to fete Gagarin and Titov in the square in front of headquarters. Kamanin finds the event very warm but poorly organised. At 19:00 Smirnov chairs the meeting of the State Commission in the conference hall of the MIK. Korolev declares the spacecraft and launch vehicle ready; Kamanin declares the cosmonauts ready. Nikolayev is formally named the commanding officer of Vostok 3, and Popovich of Vostok 4. Rudenko gets Popovich's name wrong - his second serious mistake. He had earlier called the meeting for the wrong time.

1962 August 9 - .

- Vostok 3 rollout - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Keldysh,

Korolev,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Smirnov.

Program: Vostok,

Soyuz.

Flight: Vostok 3,

Vostok 4.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

At the MIK Popovich finally trains in his suit in the seat 'as planned'. At 11:30 Smirnov, Korolev, and Keldysh inspect the new space food prepared for the flight, then meet with the cosmonauts. The Soyuz spacecraft is discussed - the cosmonauts want to have a mock-up commission. Afterwards the pilots conduct more training in their flight suits. At 21:00 Vostok 3 is rolled out from Area 10 to the pad. There was a two hour delay due to the need to reinspect the fasteners on the ejection seat - use of unauthorised substitutes was detected on other seats.

1962 November 1 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Chelomei takes over Lavochkin and Myasishchev OKBs - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Chelomei, Khrushchev, Lavochkin, Myasishchev. Program: Lunar L1. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-L1. At Khrushchev's decision Chelomei takes over Lavochkin's OKB-301 and Myasishchev's OKB-23. Lavochkin had built objects 205, 207, 400 (SA-1,2,5); Chelomei UR-96 ABM-1..

1962 November 16 - .

- Meeting of the Soviet Ministers - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Vostok,

Soyuz.

Flight: Vostok 7,

Vostok 8,

Vostok 9.

They agree to a plan for a national centrifuge facility: specifications to be determined in 1963, and the facility completed by 1967. They are not if favour of building more Vostoks - they want to move on to the Soyuz spacecraft. But this will produce an 18 to 24 month gap in Soviet manned spaceflight, during which the Americans will certainly catch up (Cooper's one-day Mercury flight is already scheduled).

1962 December - .

- Soyuz draft project completed. - . Nation: Russia. Program: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz A, Soyuz B, Soyuz P, Soyuz R, Soyuz V. The draft project for a versatile manned spacecraft included the Soyuz-A circumlunar spacecraft, the military Soyuz-P fighter and Soyuz-R reconn bird..

1962 December 6 - .

- Soviet Space Plans for 1963-1964 - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Smirnov,

Ustinov.

Program: Soyuz,

Vostok,

DS.

Flight: Vostok 7,

Vostok 8,

Vostok 9.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V,

Vostok,

Zenit-2 satellite,

Zenit-4.

Meeting of the Interdepartmental Soviet of the Academy of Sciences reviews space exploration plans. In the next two years, 5-6 Luna probes will be sent to the moon, including soft landers with a mass of 100 kg, and orbiters to map the surface. There will be flybys and landings of Mars and Venus. Two Zond spacecraft will study the space environment out to 20 million kilometres from the earth. In earth orbit, 10 Zenit spy satellites, 10 to 12 Vostok manned spacecraft, 4 to 6 Soyuz spacecraft, and 10 to 12 Kosmos satellites will be launched. The Kosmos will fly missions in meteorology, communications, television transmission, and heliographic, and geological studies. Kamanin finds this a good program, but it nearly all relies on a single launch pad and one-time transmission of data from a few satellites. The military plan is not reviewed; it must go through the VPK Military-Industrial Commission first. An Expert Commission is to be formed on the Soyuz spacecraft. Smirnov and Korolev have dictated a letter to Ustinov asking that eight more Vostoks be built. On the other hand, some on the general staff want 60 cosmonauts trained in the next two to three years, to support 8 to 10 flights of single-place spacecraft and 7 to 8 flights of multiplace spacecraft.

1963 January 21 - .

- VVS Review of Soyuz - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 11.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz P,

Soyuz R,

Soyuz V.

The primary objective of the design is to achieve docking to two spacecraft in earth orbit. Secondary objectives are the operation of scientific and military equipment from the spacecraft. Three different spacecraft, all launched by an R-7 derived booster, are required to achieve this:

- 7K spacecraft, capable of carrying three men into space and returning them to earth. The 5.5 tonne spacecraft has three modules, including the BO living module and the SA re-entry capsule

- 9K booster stage, with a fuelled mass of 18 tonnes. After docking with the 7K this is capable of boosting the combined spacecraft to earth escape velocity. The 9K is equipped with a 450 kgf main engine and orientation engines of 1 to 10 kgf. It will have 14 tonnes propellant when full loaded. Four sequential docking with a tanker spacecraft will be required to fill the tanks before the final docking with the 7K.

- 11K tanker, with a mass of 5 tonnes.

The system will conduct fuellings and dockings in a 250 km altitude parking orbit, and be boosted up to 400,000 km altitude on lunar flyby missions. The system will be ready in three years. Military variants proposed are the Soyuz-P and Soyuz-R. Each spacecraft will have 400 kg of automatic rendezvous and docking equipment. Manual docking will be possible once the spacecraft are within 300 m of each other.

Korolev still insists on an unguided landing and categorically rejects the use of wings. A parachute will deploy and slow the capsule to 10 m/s. Then a retrorocket will fire just before impact with the earth to provide a zero-velocity soft landing. Korolev still insists that spacesuits will not be carried for the crew. First test flight of the 7K, without docking, could not occur until the second half of 1964.

1963 February 1 - . LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Soyuz 11A511.

- Soyuz 'leaves drafting boards' - . Nation: Russia. Program: Lunar L1. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz A. Soyuz 'leaves drafting boards'..

1963 February 16 - .

- Plethora of projeects - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Vershinin. Program: Vostok, Soyuz. Flight: Vostok 5, Vostok 6, Vostok 6A, Vostok 7. Spacecraft: Raketoplan, Soyuz A, Vostok. Vershinin says the Soviet Union can't work on the Vostok, Soyuz, and Raketoplan manned spacecrafft all at the same time. But he still wants fo fly four Vostoks by the end of the year..

1963 March 21 - . LV Family: N1. Launch Vehicle: N1 1964.

- Presidium of Inter-institution Soviet - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Chelomei,

Glushko,

Keldysh,

Korolev.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

The expert commission report on Soyuz is reviewed by the Chief Designers from 10:00 to 14:00. The primary objective of the Soyuz project is to develop the technology for docking in orbit. This will allow the spacecraft to make flights of many months duration and allow manned flyby of the moon. Using docking of 70 tonne components launched by the N1 booster will allow manned flight to the Moon, Venus, and Mars. Keldysh, Chelomei and Glushko all support the main objective of Soyuz, to obtain and perfect docking technology. But Chelomei and Glushko warn of the unknowns of the project. Korolev agrees with the assessment that not all the components of the system - the 7K, 9K, and 11K spacecraft - will fly by the end of 1964. But he does argue that the first 7K will fly in 1964, and the first manned 7K flight will come in 1965.

1963 September - .

- Korolev earth orbit rendezvous L3 manned lunar lander design. - . Nation: Russia. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: L3-1963. This L3 design was a 200 tonne direct-lander requiring three launches of his giant N1 rocket and assembled in low earth orbit..

1963 November 30 - .

- 1964 Flight Plans - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Vostok,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Vostok 7,

Vostok 8,

Vostok 9.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V,

Voskhod.

Four Vostoks are planned for 1964, one of these with dogs and other biological specimens, which will fly for ten days at altitudes of up to 600 km. This is to be followed by an eight day manned flight, then two Vostoks on a ten-day group flight. The altitude for these latter flights will be decided after the results of the dog flight. Then, by the end of the year, the first Soyuz flights will be made. Two to three of the new spacecraft are being prepared. Therefore the crews must start training for circumlunar flights and cislunar navigation. Kamanin decides that he must select 3-4 navigators, 1-2 mathematicians, and 2-3 astronomers to make up a training group of cosmonaut-navigators for these flights.

1963 December 7 - .

- Crews for 1964 - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Nikolayev,

Rudenko,

Tereshkova.

Program: Vostok,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz A-1,

Soyuz A-2,

Soyuz A-3,

Soyuz A-4,

Vostok 7,

Vostok 8,

Vostok 9.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V,

Voskhod.

Kamanin meets with Rudenko, to discuss selection of three crews for Vostok and three crews for Soyuz flights in 1964. Ioffe reports that the Soyuz docking simulator will be completed by 25 December. Tereshkova, Nikolayev, and Bykovsky are in Indonesia on a public relations tour, to be followed by Burma.

1963 December 16 - .

- Yerkina wedding - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Dementiev,

Korolev,

Ponomaryova,

Tereshkova,

Tsybin,

Yerkina.

Program: Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz A-1,

Soyuz A-2,

Soyuz A-3,

Soyuz A-4.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A.

The cosmonaut weds at the TsPK cosmonaut centre, and 80 guests attend. Of the female cosmonauts, only Ponomaryova is not yet married. However the next female flight will be made no earlier than 1965-1966. Tereshkova looks tired after her tour to Southeast Asia - and she's supposed to go to Ghana on 10 January! Korolev claims that the Soyuz schedule, as laid out in the resolution of 4 December 1963, is still realistic. He will have the first Soyuz flight in August 1964 and the second and third in September 1964. Ivanovskiy doesn't believe it will be possible to make any flights until 1965. Korolev and Tsybin disccuss Shcherbakov's design for a rocket-propelled high-altitude glider. This concept was supported by the VVS, but Dementiev was against it and it was killed in the bureaucracy.

1964 February 12 - . LV Family: N1. Launch Vehicle: N1 1962.

- Kremlin meeting on lunar landing plans - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Lunar L3.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: L3-1963.

VVS officers meet with O G Ivanovskiy for two hours. The Communist Party plans a lunar expedition in the 1968-1970 period. For this the N1 booster will be used, which has a low earth orbit payload of 72 tonnes. The minimum spacecraft to take a crew to the lunar surface and back will have a minimum payload of 200 tonnes; therefore three N1 launches will be required to launch components, which will have to be assembled in orbit. However all of these plans are only on paper, and Kamanin does not see any way the Soviet Union can beat the Americans to the moon, who are already flying Apollo hardware for that mission.

1964 June 23 - .

- Soyuz crews. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Beregovoi, Rudenko, Shatalov. Program: Lunar L1. Flight: Soyuz A-1, Soyuz A-2, Soyuz s/n 3/4. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz A. Kamanin discusses candidates for the first five Soyuz flights. Rudenko wants Beregovoi and Shatalov named as flight commanders, but Kamanin wants the commanders to be cosmonauts with previous flight experience..

November 1964 - .

- No direction on space from new Soviet leadership. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bushuyev,

Korolev,

Okhapkin.

Program: Lunar L1,

Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Spacecraft: LK-1,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

After the triumph of the Voskhod-1 flight, Korolev gathers a group of his closest associates in his small office - Chertok, Bushuyev, Okhapkin, and Turkov. Firm plans do not exist yet for further manned spaceflights. Following the traditional Kremlin celebrations after the return of the Voskhod 1 crew, he has heard no more from the new political management. Khrushchev's old enthusiasm for space does not exist in the new leadership. Korolev is angry. "The Americans have unified their forces into a single thrust, and make no secret of their plans to dominate outer space. But we keep our plans secret even to ourselves. No one has agreed on our future space plans - the opinion of OKB-1 differs from that of the Minister of Defense, which differs from that of the VVS, which differs from that of the VPK. Some want us to build more Vostoks, others more Voskhods, while within this bureau our priority is to get on with the Soyuz. Brezhnev's only concern is to launch something soon, to show that space affairs will go better under his rule than Khruschev's." Korolev however does not think the new leadership will support continuation of Chelomei's parallel lunar project. Okhapkin speaks up. "Do not underestimate Chelomei. He is of the same design school as Tupolev and Myasishchev. If we give him the will and the means, his products will equal those of the Americans. Now is the right moment to combine forces with Chelomei".

1965 March 1 - .

- Soyuz 7K-PPK cancelled. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Chelomei. Program: Almaz. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz PPK. Based on successful test flights of Chelomei's unmanned interceptor-sputnik prototypes (Polyot 1 and 2), the Soyuz 7K-PPK manned interceptor version is cancelled..

1965 April 2 - .

- VVS role in space - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Artyukhin,

Belyayev,

Beregovoi,

Brezhnev,

Demin,

Katys,

Korolev,

Leonov,

Ponomaryova,

Rudenko,

Shatalov,

Solovyova,

Tereshkova,

Volynov.

Program: Voskhod,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A.

Kamanin visits Korolev and tells him that in an upcoming meeting between the cosmonauts and Brezhnev and Kosygin, they are going to push for the VVS to be given a leading role in the exploration of space, including the necessity to improve the cosmonaut training centre with 8 to 10 simulators for Voskhod and Soyuz spacecraft, and development within the VVS of competence in space technology. Korolev is not opposed to this, but says he doubts the VVS leadership will support acquiring the new mission. Kamanin then indicates to Korolev his proposed crews for the upcoming Voskhod missions: Volynov-Katys, Beregovoi-Demin, Shatalov-Artyukhin. Kamanin hopes that Korolev will support Volynov as the prime candidate against Marshall Rudenko's favouring of Beregovoi. Kamanin then raises the delicate issue of Korolev's unfavourable opinion of Tereshkova. After her flight, Korolev angrily said: "I never want to have anything to do with these women again". Kamanin does not believe his remarks were meant seriously, and broaches the subject of training Soloyova and Ponomaryova for a female version of Leonov's spacewalk flight. Korolev says he will seriously consider the suggestion.

1965 April 20 - .

- Cosmonaut tours - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Nikolayev,

Tereshkova.

Program: Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz A.

The demand for cosmonaut appearances is constant; over 90% of such requests have to be denied. Tereshkova and Nikolayev are especially in demand - France wants them for two or three days, and there are also requests from Mongolia, Finland, Norway, Greece, Iran, Rumania, USA, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and many others. As far as progress on cosmonaut trainers, General Ponomaryov, who has no interests in space, is hampering development efforts. So far his interference has delayed completion of the docking trainer by six months.

1965 July 6 - .

- Soyuz hot mock-up - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-LOK.

Chertok argues for the necessity of adding one Soyuz to production and using it as an iron bird - a hot mock-up on which avionics and electrical systems can be integrated and tested. Gherman Semenov and Turkov convince Korolev that this cannot be done within the existing schedules.

1965 August 18 - .

- Soyuz development program reoriented; Soyuz 7K-OK earth orbit version to be built in lieu of Soyuz A. - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz A-1,

Soyuz A-2,

Soyuz A-3,

Soyuz A-4,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft: LK-1,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

Military-Industrial Commission (VPK) Decree 180 'On the Order of Work on the Soyuz Complex--approval of the schedule of work for Soyuz spacecraft' was issued. It set the following schedule for the new Soyuz 7K-OK version: two spacecraft to be completed in fourth quarter 1965, two in first quarter 1966, and three in second quarter 1966. Air-drop and sea trails of the 7K-OK spacecraft are to be completed in the third and fourth quarters 1965, and first automated docking of two unmanned Soyuz spacecraft in space in the first quarter of 1966. Korolev insists the automated docking system will be completely reliable, but Kamanin wishes that the potential of the cosmonauts to accomplish a manual rendezvous and docking had been considered in the design. With this decree the mission of the first Soyuz missions has been changed from a docking with unmanned Soyuz B and V tanker spacecraft, to docking of two Soyuz A-type spacecraft. It is also evident that although nothing is official, Korolev is confident he has killed off Chelomei's LK-1 circumlunar spacecraft, and that a Soyuz variant will be launched in its place.

1965 August 20 - .

- Soyuz crews - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Artyukhin,

Beregovoi,

Bykovsky,

Demin,

Feoktistov,

Gagarin,

Katys,

Komarov,

Korolev,

Nikolayev,

Volynov.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 1,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 2,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-L1,

Voskhod.

Kamanin calls Korolev, finds he is suffering from very low blood pressure (100/60). Kamanin suggests that candidates for the commander position in the first two Soyuz missions would be Gagarin, Nikolayev, Bykovsky, or Komarov. Korolev agrees basically, but says that he sees Bykovsky and Nikolayev as candidates for the first manned lunar flyby shots. Kamanin suggests Artyukhin and Demin for the engineer-cosmonaut role on the first Soyuz flights, but Korolev disagrees, saying Feoktistov has to be aboard. However Korolev agrees with Kamanin's selection for the next Voskhod flight - Volynov/Katys as prime crew, Beregovoi/Demin as backups. Later Kamanin corresponds with Stroev over modification of an Mi-4 helicopter as a lunar lander simulator.

1965 August 24 - .

- Soyuz-VI program started.. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Kozlov.

Flight: Gemini 4,

Soyuz VI Flight 1.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz VI,

Gemini,

MOL.

Central Committee of the Communist Party and Council of Soviet Ministers Decree 'On expansion of military space research and on 7K-VI Zvezda' was issued. In June 1965 Gemini 4 began the first American experiments in military space. At the same time the large military Manned Orbital Laboratory space station was on the verge of being given its final go-ahead. These events caused a bit of a panic among the Soviet military, where the Soyuz-R and Almaz projects were in the very earliest stages of design and would not fly until 1968 at the earliest. VPK head Leonid Smirnov ordered that urgent measures be taken to test manned military techniques in orbit at the earliest possible date. Modifications were to be made to the Voskhod and Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft to assess the military utility of manned visual and photographic reconnaissance; of inspection of enemy satellites from orbit; attacking enemy spacecraft; and obtaining early warning of nuclear attack. The decree instructed Kozlov to fly by 1967 a military research variant of the Soyuz 7K-OK 11F615.

1965 August 28 - .

- Korolev secretly puts Voskhod production on back burner. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Gemini 5,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5,

Voskhod 6.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod,

Gemini.

It is becoming clear that in order to ever get Soyuz into space it is necessary to clear all decks at OKB-1. After Voskhod-2 the Soviet manned space plans are in confusion. The Americans have flown Gemini 5, setting a new 8-day manned space endurance record - the first time the Americans are ahead in the space race. They rubbed salt into the Soviet wound by sending astronauts Cooper and Conrad on a triumphal world tour. This American success is very painful to Korolev, and contributes to his visibly deteriorating health. In the absence of any coherent instructions from the Soviet leadership, Korolev makes a final personal decision between the competing manned spacecraft priorities. Work on completing a new series of Voskhod spacecraft and conducting experiments with artificial gravity are unofficially dropped and development and construction of the new Soyuz spacecraft is accelerated. The decision is shared only with the OKB-1 shop managers. One of Korolev's "conspirators" lays on Chertok's table the resulting new Soyuz master schedule. The upper left of the drawing has the single word "Agreed" with Korolev's signature. The only other signatures are those of Gherman Semenov, Turkov and Topol - Korolev has ordered all other signature blocks removed. Chertok is enraged. The plan provides for the production of thirteen spacecraft articles for development and qualification tests by December 1965! These include articles for thermal chamber runs, aircraft drop tests, water recovery tests, SAS abort systems tests, static and vibration tests, docking system development rigs, mock-ups for zero-G EVA tests aboard the Tu-104 flying laboratory, and a full-scale mock-up to be delivered to Sergei Darevskiy for conversion to a simulator. Chertok is enraged because the plan does not include dedicating one spaceframe to use as an 'iron bird' hot mock-up on which the electrical and avionics systems can be integrated and tested. Instead two completed Soyuz spacecraft are to be delivered to OKB-1's KIS facility in December and a third in January 1966. These will have to be used for systems integrations tests there before being shipped to Tyuratam for spaceflights.

1965 September 1 - . LV Family: N1. Launch Vehicle: N1 1964.

- Voskhod/Soyuz crewing plans - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Anokhin,

Artyukhin,

Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Katys,

Kolodin,

Komarov,

Korolev,

Matinchenko,

Nikolayev,

Ponomaryova,

Solovyova,

Volynov.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L3.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 5.

Spacecraft: LK,

LK-1,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Voskhod.

Kamanin meets with Korolev at 15:00 to discuss crew plans. As Soyuz pilot candidates, Kamanin proposes Gagarin, Nikolayev, Bykovsky, Komarov, Kolodin, Artyukhin, and Matinchenko. Korolev counters by proposing supplemental training of a supplemental group of engineer-cosmonauts from the ranks of OKB-1. He calls Anokhin, his lead test pilot, informs Korolev that there are 100 engineers working at the bureau that are potential cosmonauts candidates, of which perhaps 25 would complete the selection process. Kamanin agrees to assist OKB-1 in flight training of these engineer-cosmonauts. Kamanin again proposes Volynov and Katys as prime crew for the Voskhod 3 12-15 day flight. Korolev reveals that, even though Kamanin will have the crew ready by October, the spacecraft for the flight may not yet even be ready by November - Kamanin thinks January 1966 is more realistic. The discussion turns to the female EVA flight - Ponomaryova as pilot, Solovyova as spacewalker. It is decided that a group of 6 to 8 cosmonauts will begin dedicated training in September for lunar flyby and landing missions. Korolev advises Kamanin that metal fabrication of the N1 superbooster first article will be completed by the end of 1965. The booster will have a payload to low earth orbit of 90 tonnes, and later versions with uprated engines will reach 130 tonnes payload. Korolev foresees the payload for the first N1 tests being a handful of Soyuz spacecraft.

1965 September 8 - .

- American vs Soviet programs - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Gemini 5.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Kamanin reviews a speech by President Johnson to the US Congress. From 1954-1965 the USA spent 34 billion dollars on space, $ 26.4 billion of that in just the last four years. The Soviet Union has spent a fraction of that, but the main reason for being behind the US is poor management and organisation structure, in Kamanin's view. With the US now having the lead in space, and the Gemini 5 results showing they openly used the manned flight for military reconnaissance, the Soviet leadership has awakened to the threat. They are demanding answers - how many cosmonauts does the US have in training? What are Soviet plans for use of hydrogen-oxygen fuel cells in space? What are the flight schedules for Voskhod and Soyuz? In contradiction to these demands, Kamanin is finding it difficult to obtain funding to keep the Tu-104 weightlessness trainer flying....

1965 September 22 - .

- Tereshkova manoeuvres - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Feoktistov,

Korolev,

Ponomaryova,

Tereshkova.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 5.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Tereshkova confides to Kamanin that Ponomaryova is not ready for her scheduled spaceflight. Kamanin does not believe it - he has heard it from no other cosmonauts, and he has spoken to Ponomaryova often over the years. Flight plans for 1965-1966 are reviewed. The pluses and minuses of each cosmonaut in advanced training for Voskhod flights is reviewed. The latest plan for the Voskhod-3 flight is for a 20-day flight with two cosmonauts (in an attempt to upstage the planned Gemini 7 14-day flight). This is followed by another tense phone call from Korolev, then Feoktistov complaining about inadequate VVS support for the Soyuz landing system trials at Fedosiya (no Mi-6 helicopter as promised; incorrect type of sounding rockets for atmospheric profiles; insufficient data processing capacity; inadequate motor transport). When Kamanin appeals to Finogenov on the matter, he is simply told that if "Korolev is unhappy with out facilities, let him conduct his trials elsewhere". Without the support of the VVS leadership, it is up to Kamanin to try to improve the situation using only his own cajoling and contacts.

1965 October 22 - .

- Gagarin writes a letter to Brezhnev - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Belyayev, Biryuzov, Brezhnev, Bykovsky, Gagarin, Grechko, Leonov, Nikolayev, Titov. Program: Lunar L1, Voskhod, Soyuz. Gagarin has sent a letter to Brezhnev, complaining of the poor organisation of the Soviet space program. The Kremlin has received it... reaction is awaited. The letter specifically cites the multitude of space projects and de-emphasis of manned efforts.. Additional Details: here....

1965 October 26 - .

- Thoughts on Gemini 6 - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Gemini 6.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Kamanin notes the aborted first launch attempt of Gemini 6, but expects the Americans to achieve the first space docking, using the crew as pilots to fly the spacecraft. He curses Korolev and Keldysh for wasting three years trying to develop a fully automated system for Soyuz, which has put the Soviet Union well behind the Americans. He does not see any equivalent Soviet achievement until the end of 1966...

1965 November 1 - .

- OKB-1 learns of Gagarin letter - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Brezhnev,

Gagarin,

Korolev,

Tsybin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Tsybin has learned through his Ministry of Defence contacts of Gagarin's letter to Brezhnev. He hears that they have criticized the space policy of the Minister of Defence and proposed that the VVS manage Soviet manned spaceflight. The letter also reportedly requests production of a new series of Voskhods to fill in the manned spaceflight gap created by delays in the Soyuz program. Korolev is remarkably unperturbed that he had not heard of the letter, and that Gagarin never said anything to him about it.

1965 November 24 - .

- Kamanin and Korolev - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Afanasyev, Sergei,

Korolev,

Pashkov,

Smirnov,

Tyulin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5,

Voskhod 6.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

Kamanin has his first face-to-face meeting with Korolev in 3 months - the longest delay in three years of working together. Their relationship is at low ebb. Despite having last talked about the next Voskhod flight by the end of November, Korolev now reveals that the spacecraft are still incomplete, and that he has abandoned plans to finish the last two (s/n 8 and 9), since these would overlap with planned Soyuz flights. By the first quarter of 1966 OKB-1 expects to be completing two Soyuz spacecraft per quarter, and by the end of 1966, one per month. Voskhod s/n 5, 6, and 7 will only be completed in January-February 1966. Korolev has decided to delete the artificial gravity experiment from s/n 6 and instead fly this spacecraft with two crew for a 20-day mission. The artificial gravity experiment will be moved to s/n 7. Completion of any of the Voskhods for spacewalks has been given up; future EVA experiments will be conducted from Soyuz spacecraft. Korolev says he has supported VVS leadership of manned spaceflight in conversations with Tyulin, Afanasyev, Pashkov, and Smirnov.

1965 November 25 - .

- New cosmonauts - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Babiychuk,

Korolev,

Voronin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1,

.

Flight: Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft Bus: Vostok.

Spacecraft: Voskhod.

Kamanin meets the 22 new cosmonaut candidates. Some higher officers have questioned the need for so many cosmonauts in training - 32 are already available. But Kamanin sees plans for 40 to 50 manned spaceflights over the next 3 to 4 years. He expects to see some of these cosmonauts walking on the moon, and others on expeditions to other planets. Later Kamanin has to call Korolev after a dispute breaks out between Voronin and Babiychuk and Frolov. Voskhod 3 will not be cleared for flight because the trials of the long-duration environmental control system will not be undertaken at designer Voronin's institute. Furthermore it is still the position of the military that Voskhod 4 should conduct some military experiments.

1965 November 30 - .

- Problems with the Igla system for Soyuz - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gagarin,

Korolev,

Mnatsakanian.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5,

Voskhod 6.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

After a meeting with Kamanin, Korolev tells Chertok in confidence that Gagarin is training for a flight on a Soyuz mission. Chertok responds that it will take him at least a year to complete training, but that doesn't matter, since Mnatsakanian's Igla docking system will not be ready than any earlier than that. Korolev explodes on hearing this. "I allowed all work on Voskhod stopped so that the staff can be completely dedicated to Soyuz. I will not allow the Soyuz schedule to slip a day further". Turkov had been completing further Voskhods only on direct orders from the VPK and on the insistence of the VVS. Aside from military experiments, further Voskhod flights were meant to take back the space endurance record from the Americans. Korolev has derailed those plans without openly telling anyone in order to get the Soyuz flying.

1965 December 4 - .

- Voskhod trainers - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gorbatko,

Popovich,

Volynov.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

At LII Kamanin reviews progress on the Voskhod trainer. It should be completed by 15 December, and Volynov and Gorbatko can then begin training for their specific mission tasks. The Volga docking trainer is also coming around. Popovich is having marital problems due to his wife's career as a pilot. Popovich will see if she can be assigned to non-flight duties.

1965 December 8 - .

- Soyuz VI - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gorbatko,

Volynov.

Flight: Gemini 7,

Soyuz VI Flight 1,

Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz VI,

Gemini.

Kamanin meets with an engineering delegation from Kuibyshev. They are seeking a close relationship with the cosmonaut cadre in development of the military reconnaissance version of Soyuz, which they are charged with developing. They have already been working with the IAKM for over a year in establishing he basic requirements. Kamanin finds this refreshing after the arms-length relationship with Korolev's bureau. Meanwhile Gemini 7 orbits above, and there is not the slightest word on the schedule for Volynov-Gorbatko's Voskhod 3 flight, which would surpass the new American record.

1965 December 31 - . LV Family: N1. Launch Vehicle: N1 1964.

- Daunting year ahead - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soviet Lunar Landing,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 1.

Spacecraft: LK,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Kamanin looks ahead to the very difficult tasks scheduled for 1966. There are to be 5 to 6 Soyuz flights, the first tests of the N1 heavy booster, the first docking in space. Preparations will have to intensify for the first manned flyby of the moon in 1967, following by the planned first Soviet moon landing in 1967-1969. Kamanin does not see how it can all be done on schedule, especially without a reorganization of the management of the Soviet space program.

1966 January 8 - .

- Space trainers - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Mozzhorin,

Tyulin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

Tyulin and Mozzhorin review space simulators at TsPK. The 3KV and Volga trainers are examined. Tyulin believes the simulators need to be finished much earlier, to be used not just to train cosmonauts, but as tools for the spacecraft engineers to work together with the cosmonauts in establishing the cabin arrangement. This was already done on the 3KV trainer, to establish the new, more rational Voskhod cockpit layout. Tyulin reveals that the female Voskhod flight now has the support of the Central Committee and Soviet Ministers. He also reveals that MOM has promised to accelerate things so that four Voskhod and five Soyuz flights will be conducted in 1966. For 1967, 14 manned flights are planned, followed by 21 in 1968, 14 in 1969, and 20 in 1970. This adds up to 80 spaceflights, each with a crew of 2 to 3 aboard. Tyulin also supports the Kamanin position on other issues - the Voskhod ECS should be tested at the VVS' IAKM or Voronin's factory, not the IMBP. The artificial gravity experiment should be removed from Voskhod and replaced by military experiments. He promises to take up these matters with Korolev.

1966 January 14 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Korolev's death - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Beregovoi,

Korolev,

Kuznetsov, Nikolai F,

Kuznetsova,

Mishin,

Petrovskiy,

Ponomaryova,

Shatalov,

Shonin,

Solovyova,

Tereshkova,

Volynov,

Yerkina.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.