Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Almaz

Almaz History

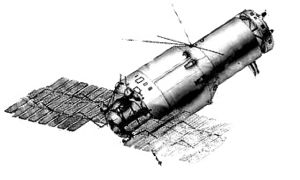

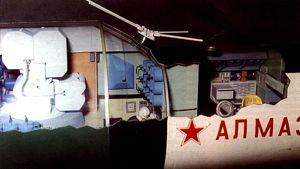

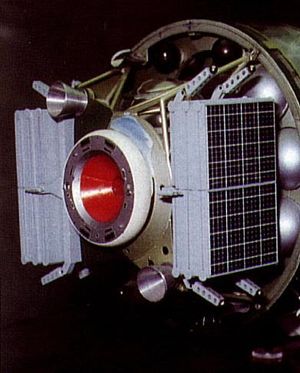

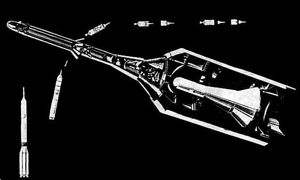

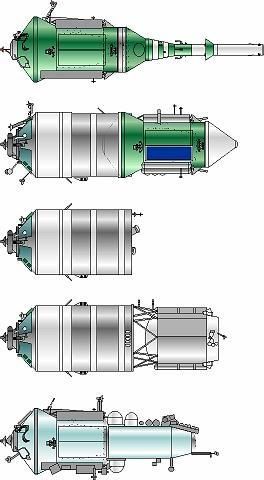

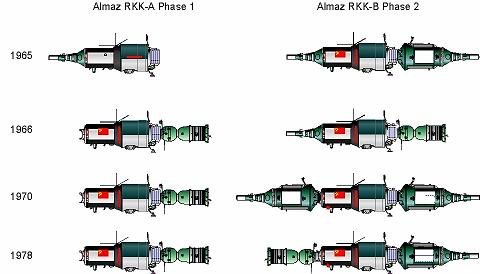

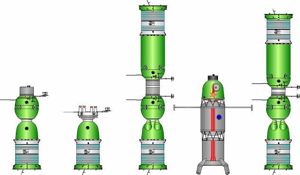

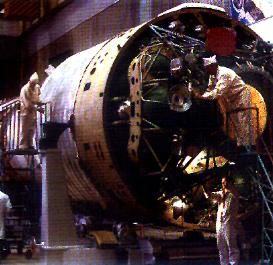

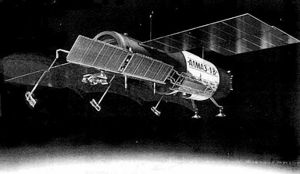

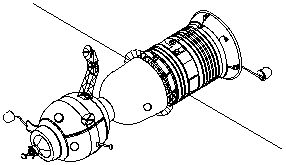

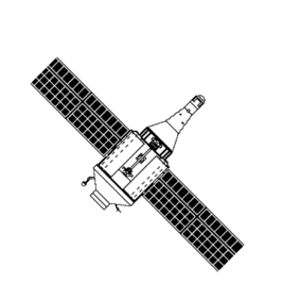

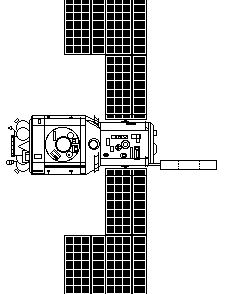

The changing configurations of the Almaz military space station throughout its long year history. The planned TKS ferry was replaced by the Soyuz from 1966 to 1970. From 1970 on Soyuz would be used for Phase 1 flights while the TKS would be used for Phase 2 flights.

Credit: © Mark Wade

AKA: 11F71;Mech.

The initial Almaz program of 1965 consisted of two phases. In the first phase, 20 tonne Almaz APOS space stations, complete with crew and re-entry capsule, would be put in orbit by a single launch of a Proton rocket. In phase two, sustained operations would be conducted with Almaz OPS stations serviced by 20 tonne TKS manned resupply vehicles.

In 1966 this plan was revised. The first phase would now consist of the Almaz OPS stations, visited by crews launched separately aboard 6.5 tonne Soyuz transport vehicles. In this phase the value of manned space reconnaissance and targeting would be evaluated. In the second phase sustained operations would be conducted with Almaz dual-docking port stations serviced by TKS manned resupply vehicles.

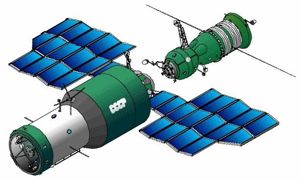

Almaz flights were delayed in 1970 when resources were diverted to a crash program to upstage the American Skylab. Partially completed Almaz stations were outfitted as civilian Salyut space station. Almaz first phase flights finally took place in 1973-1977. Three Soyuz crews successfully visited two Almaz stations. Second phase flights of Almaz-2 stations and TKS were to be flown in 1981-1982. Unmanned flight tests of the TKS, its VA re-entry capsule, and construction of dual-port Almaz stations were completed, but Phase 2 was cancelled in 1979. The three TKS already built were instead flown unmanned to civilian Salyut space stations in 1981-1985.

The nearly-complete second phase Almaz stations were converted into automated man-tended Almaz-T reconnaissance platforms. These were to be launched and visited by Soyuz crews in the first half of the 1980's. The first station was ready in 1980 but launch was held up politically until 1986. By that time the decision was taken to make the Almaz-T fully automated and eliminate the manned flights. Following an initial launch failure two Almaz-T automated stations flew in 1987-1991.

A final automated derivative was to be the Almaz-1V civilian earth resources satellite. This was authorised in 1986 but the Soviet Union collapsed before it was built. Attempts in the 1990's to interest commercial customers in earth-resource derivatives of the Almaz and TKS were unsuccessful. However Almaz and TKS derivatives were used as the Zvezda and Zarya and modules of the International Space Station.

William Thackeray, Barry Lyndon

Competing Concepts

On December 10, 1963, US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara announced the cancellation of the Dynasoar program, and the beginning of studies for a Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) - a military space station. Within the Soviet Union, two space station projects were in the preliminary design state. At design bureau OKB-1, Chief Designer Sergei Korolev planned a huge 75 tonne OS space station for launch atop his N1 booster. Vladimir Nikolayevich Chelomei headed the competing OKB-52 design bureau and was Korolev’s arch-rival. He had received approval for development of his UR-500 booster with the backing of Nikita Khrushchev. One payload planned for the booster was the 12 tonne TAS Heavy Automated Station. A heavier manned derivative was envisioned for launch by a later upgraded version of the Proton. But these were longer-term projects and MOL represented an immediate challenge.

The initial response was authorisation for Chief Designer Dmitri Ilyich Kozlov at the Samara Filial of Korolev's bureau to begin design of Soyuz-R. The Soyuz-R system consisted of two separately launched spacecraft derived from the Soyuz design, with the docked complex having a total mass of 13 tonnes. The small orbital station 11F71 would be equipped with photo-reconnaissance and ELINT equipment. To dock with the station Samara developed the Soyuz 7K-TK 11F72 transport spacecraft. Soyuz-R was included by the Defence Ministry in the 1964-1969 five-year space reconnaissance plan, issued on 18 June 1964.

On 12 October 1964, only two days before the overthrow of Khrushchev, Chelomei obtained permission to begin development of a larger manned military space station, the Almaz. This 20 tonne station would take three cosmonauts to orbit in a single launch of his uprated UR-500K Proton rocket. Therefore there were now two competing projects for the same mission - Almaz and Soyuz-R.

Almaz - 1965 Concept

On 1 January 1965 the decision was formalised in the decree of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and Council of Soviet Ministers 'On work on space stations at OKB-52'. This defined Almaz as an OOS - Manned Orbital Station - in specific reply to the USAF Manned Orbiting Laboratory programme. Two phases of the project - RKK A (Rocket-spacecraft complex A, the entire system including the Proton UR-500K launch vehicle) and RKK B were planned. The decree authorised Chelomei to proceed immediately with build of the Almaz RKK 'A' version. Flight of the first Almaz RKK-A was set for 1968. The draft project for the RKK-B, with three crew, 1 to 2 year life, was to be completed by 21 June 1967.

The two phases were defined in detail as follows:

- RKK-A / APOS - Autonomous Piloted Orbital Station. The first station was a self-contained concept similar to the MOL, equipped with a VA re-entry capsule and a one to three month active life. The station section was designated OPS - Orbital Piloted Station. The OPS and VA were given the article numbers 11F71 and 11F74 (assigned the same article number, this clearly indicated the OPS was considered a replacement for the Soyuz-R station). Total mass was 15 tonnes for the OPS and 4.9 tonnes for the VA. Access to the station was via an airlock in the heat shield of the VA. No dockings would be required in this phase, which was planned to last for three years. Project-construction work was to be completed by the end of 1969 of a bare-bones station. This first OPS Almaz 0101-1 would have only 70 of the 300 systems planned for the full 'B' complex.

- RKK-B / OPS+TKS, with a one year active life. In this case crews would be rotated by the TKS ferry spacecraft to the OPS. Both the OPS and TKS would be equipped with VA re-entry capsules. Almaz OPS itself was to weigh 17.8 tonnes, with 100 cubic metres of total internal volume, while the TKS ferry came in at 17.5 tonnes and 45 cubic metres. The OPS and TKS were each equipped with a VA re-entry capsule, with a mass of 4.2 tonnes each. The complete complex provided a grand total of 89.4 cubic metres of habitable volume for six crew. The TKS had enough guidance, consumables, and electricity to dock dozens of times with the station. It could also manoeuvre independently. The VA capsules were designed for ten reuses. Almaz was designed to accomplish both scientific and military research.

All together RKK-B Almaz was designated the PRKK (Piloted Rocket Space Complex). It consisted of the OPS (Almaz), the TKS, the VA's, and KSI's (Special Information Capsules - small capsules for returning film and experiment results from orbit). Three to four dockings of the TKS would rotate crews and bring fresh supplies to the station. Phase B was to last 5 to 6 years. Systems planned for the station included the Agat photo-reconnaissance system; the R1-P sextant; the AI-ZR astro-tracker, plus BsVM, STR, SNIR, BIPS, Kashtan and Igla.

OKB-52 began development of the Almaz on a crash basis. 500 people worked on the control system and engines alone, with another 1000 on all other systems.

Changes in Plan - the Soyuz as Ferry to Almaz

Meanwhile the Soyuz-R advanced project was completed by Kozlov, but the Soyuz-derived station had become too heavy for the planned Soyuz launch vehicle. The perceived urgent need for manned test of military technology space led the leadership to authorise Kozlov to develop yet another military Soyuz, the single-launch Soyuz-VI. These directions were embodied in the Central Party resolution of 24 August 1965, which instructed Kozlov’s KB to fly a military research variant of the Soyuz 7K-OK by 1967.

It seems that weight growth during the course of 1965 also made the Chelomei single-launch APOS concept too heavy for launch by the Proton booster. In January 1966 Korolev died unexpectedly. OKB-1 was leaderless for nearly a year until his deputy, Vasiliy Pavlovich Mishin, was selected as his replacement. This was perceived as giving Chelomei an opening to kill Soyuz-R, although the final result was a compromise that pleased no one. On 30 June 1966 Ministry of General Machine Building (MOM) Decree 145ss 'On approval of the 7K-TK as transport for the Almaz station' was issued. It was decided that the 11F71 Soyuz-R space station would be cancelled and the Almaz OPS would be developed in its place. Almaz was assigned the index number previously allocated to the Soyuz-R station, and Kozlov was ordered to hand over to Chelomei all of the work completed in relation to the station. However Kozlov's Soyuz 7K-TK ferry was to continue in development to transport crew to the Almaz OPS, at least in Phase A of the project.

G A Yefremov escorted the Soyuz-R material from Kozlov's Samara plant to Chelomei's TsKBM organisation. The documents showed what a complex development was required to achieve the military's requirements. In Samara, work continued with release of the technical documentation of the 7K-TK. However due to delays in the Almaz all work on further development of the 7K-TK was suspended on 28 December 1966. These schedule changes were embodied in Military-Industrial Commission (VPK) Decree 104 'On changes in the timeline for the Almaz program and suspension of the 7K-TK'. This was supplemented on the same day with the VPK Resolution no. 305 'On approval of work on the 7K-VI Zvezda and course of work on Almaz' . This ordered Kozlov to undertake first flight of the manned military research spacecraft 7K-VI - 11F73 Zvezda by the end of 1967. The revised Almaz Phase A now consisted of launch of three OPS stations without VA re-entry capsules. Three two-month expeditions would be launched to each station aboard 7K-TK transports. Each station of the initial series was to have a life of three to four months.

Two decrees during the course of 1967 reinforced these decisions and set an aggressive schedule: initial flight tests of Almaz-A/Soyuz 7K-TK in 1968 and entry of the system into service in 1969. (these were Ministry of General Machine Building (MOM) Decree 'On approval of work on Almaz' was issued on 9 February 1967 and Central Committee of the Communist Party and Council of Soviet Ministers Decree 'On full approval of the Almaz and 7K-TK programs' on 1 June 1967).

On 21 June 1967 the Military-Industrial Commission (VPK) Decree 'On approval of the Almaz draft project' was issued, followed by Central Committee of the Communist Party and Council of Soviet Ministers Decree 'On schedule of work on the Almaz space station' on 14 August. The revised program seemed on track for an early test flight. Almaz program development was overseen by the State Committee for Flight Technology, P Dementiev, Chairman.

To complicate matters Mishin, the new head of Korolev's design bureau, managed to kill Kozlov's Soyuz-VI project in December 1967. In its place a Soyuz-derived OIS orbital station was proposed, which seemed very similar to the earlier Soyuz-R.

Chelomei's revised Almaz draft project was presented to the Fourth Trials Directorate at Baikonur Cosmodrome in January 1968. First launch did not now seem possible until 1969. Chelomei continued to have difficulty maintaining top-level support for Almaz as the project met delay after delay. While Khrushchev was in power, Chelomei was ascendant - Sergei Nikitovich, the Secretary General's son, worked at his firm. But Chelomei was not seen as an experienced politician and had belittled Council of Ministers Deputy Chairman Dmitri Ustinov. When Brezhnev took power, Ustinov became the Communist Party Central Committee Secretary for Defence. Chelomei's influence waned.

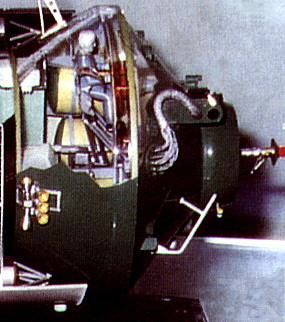

The official schedule for Almaz was held until 1969, when it became apparent that delays in subsystems deliveries would rule out any first flight until 1970. The mock-up of Almaz had been completed at Reutov in 1968 while production of station hulls was proceeding at Fili Factory 22. For Chelomei's ex-Myasischyev engineers, designing and building the structure of the station was trivial. Chertok asserted that Mishin's TsKBM could have done the same. However Almaz had a number of ambitious military and guidance systems that were desperately behind schedule. There was the large Agat camera which could be controlled in real-time by the cosmonauts and was capable of infrared detection. Using 'space binoculars' to determine if a target was clear and of interest, the entire array of sensors could be directed toward the target. Parts of the earth covered by cloud were examined using side-looking radar. All of this required high-precision guidance and orientation of the station. The station had to be pointed precisely for the target run while the panels remained oriented to the sun.

Chelomei developed the necessary complex guidance system within his own collective. His design bureau worked with the VNIIEM research institute on an electromechanical system of orientation using spherical gimbals and flywheels with great kinetic momentum (ancestors of the Mir’s 'gyrodynes'). These electrically-powered system could point the station with great precision without the expenditure of propellant.

Chelomei was also developing the Argon digital computer at the All-Union Institute of Digital Electronic Computer Technology (VNITsEVT). This computer was not in fact launched until 15 years later, for use aboard Mir! All of the technology for the Almaz station was similarly taking much longer than Chelomei expected. Therefore in the course of 1969 station spaceframes were being completed, but systems assembly had not even begun.

The DOS Program Civilian Space Station Threatens the Survival of Almaz

Other threats to the project's survival emerged. On 10 June 1969 President Nixon announced cancellation of the USAF MOL military space station program. The original impetus for development of Almaz was eliminated at a stroke. On 21 June 1969 the draft project for Mishin's OIS 11F730 military space station was issued jointly by TsKBEM and Kozlov's Filial 3. In the course of 1969 complete drawings were released for the OIS project including modules for the ferry spacecraft Soyuz 7K-S, 7K-S-I, and 7K-S-II.

On 3 July 1969 the second Soviet N1 lunar launch vehicle blew up on the pad. 17 days later, Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon, winning the moon race for the Americans. The whole reason the existence of Mishin's design bureau's simply vanished. A new high-priority project was needed.

In terms of space stations, Mishin was thinking on a much larger scale then Chelomei. Korolev had begun development of a Multi-Module Space Base (MKBS) before 1966. Mishin put Vitali Bezverbom in charge of the project. MKBS would have been a space port, which would be visited by various spacecraft, primarily reconnaissance satellites, where film would be received. The film would be replenished, the spacecraft refuelled and preventive maintenance and repairs conducted. Such work would require well-qualified crews. A number of base stations in low earth orbit would extend the working life of spacecraft, which otherwise would have to be returned to earth or de-orbited into the ocean.

MKBS also accommodated ABM and ASAT weapons, including a neutral particle beam. This was being developed by Gersh Budker at Novosibirsk. He gave a lecture to OKB-1 staff on the subject of a neutral particle beam weapon. Enthusiasm for the concept was such that there was no impediment to the start of research on including the device in the MKBS. It would be housed in a separate module of the station, as would the photographic and radar reconnaissance systems.

However MKBS was to be launched by the N1; as long as this was not available, there would be no MKBS. Almaz on the other hand did not require a new launch vehicle, although the UR-500 was in a period of intense 'baby sickness'. So while TsKBEM was in a period of analysis and instability, Reutov and Fili were building space station for the Ministry of Defence.

On one of these August 1969 days, Raushenbach, Legostayev, and Bashkin came to Mishin's deputy Chertok with a plan to take an Almaz spaceframe, install Soyuz systems, add a new docking tunnel with a hatch to reach the interior, and presto - a space station was finished. It would weigh only 18 tonnes, could be launched by a Proton UR-500K, and could be ready in one year. A new ECS would be required, but Oleg Suguchev and Ilya Lavrov confirmed this would not be a problem - they could develop a new system in one year, using existing pumps and components. Chertok checked with Isayev if the Soyuz engine unit could be adapted to handle a spacecraft of three times the mass and was told this was not a problem. Tentative discussions with potential allies within Chelomei's design bureau found support there as well.

The DOS 'long-duration orbiting station' was the result of this 'conspiracy' - an alliance of engineers at Mishin's TsKBEM Filial 1 and Chelomei's TsKBM (V N Bugayskiy, Khrunichev ZIKh factory director M I Rishiteh). They had got to know each other on the forced collaboration of the two bureaux on the L1 manned circumlunar project. They managed to go around their two chief designers and have the concept presented by D F Ustinov to the Central Committee of the USSR for Military Issues.

Almaz was converted to the DOS configuration by :

- Adding an Exit Section (PKhO) with a passive Soyuz docking system and airlock to the front of the station;

- Adding an Engine Section (AO) adapted from that of Soyuz to the rear of the station;

- Mounting Soyuz solar panels (SB) on the PKhO and AO.

At the end of 1969 Chelomei's Khrunichev factory had built 8 Almaz test stand and two flight articles. A Special Contingent within Chelomei's design bureau was formed at the end of 1968 to conduct crew tests on the ground of the stations in phase one and to make flights to Almaz in the second phase. Three-man crews had already been formed. They would conduct real-time tests on the ground during the flight and advise the flight crew of any problems.

But Mishin was opposed to the concept - he wanted to pursue the MKBS. Afanasyev and his deputy were equally opposed, and Tyulin wouldn't support the idea either. None of them wanted to take the risk. The only chance was to get to Ustinov through Communist party channels. The opportunity came in October 1969 on the flight of engineers and management to Baikonur for the Soyuz 6/7/8 flight. Feoktistov had prepared a briefing which he presented to Ustinov.

In the euphoria after the return of the Soyuz crews, the problem was how to get Ustinov to meet further with the DOS 'conspirators'. Mishin had prohibited any meetings by TsKBEM staff with the Communist Party Secretary unless Mishin was also present. Another obstacle was that Feoktistov was not a party member; how could his presence at a party meeting be explained to Mishin later?

In any event this was simply ignored. Feoktistov was present at a party meeting with Keldysh, Afanasyev, Tyulin, Serbin, and the Ministry of Defence's party cell: Strogonov, Kravtsev, and Popov. Keldysh was mainly worried how the project would affect the N1, but was reassured that the N1 had a dedicated work force, and the L3 lunar lander spacecraft engineers and workers that would work on DOS were currently idle and had no part of that work. It was finally decided to go ahead with the DOS no earlier than January, to allow time for Ministry Decrees, approval of a work plan by the VPK, preparation of a decree for signature by the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Soviet Ministers. Work began on the project in December 1969 under the initial auspices of the Academy of Sciences.

After the meeting, convinced of Ustinov's support, the 'conspirators' were left with just a year to build the station. Engineers immediately started switch from the dead-end L3 effort to DOS. Bushuev was worried that this only sealed the fate of the N1. It was in any case important that the matter be formalised quickly. Being discovered working on it would be an embarrassment.

The biggest new development required was the docking collar and hatch unit. Semenov (L1 manager, and later head of RKK Energia) was the obvious project leader - the L1 had only two flights to go and he had demonstrated on that project the ability to maintain good communications and relations with OKB-52 and Chelomei. But how did they know whether he would support the DOS concept?

The 'conspiracy' came out in the open on 6 December 1969 Afanasyev met with the Chief Designers - Pilyugin, Ryazanskiy, V Kuznetsov, and Chelomei's Deputy, Eydis. Mishin was 'sick' and Chelomei had sent his deputy, as usual, to avoid having to meet Mishin. Afanasyev started with the demand that an Almaz flight take place within less than two years, before the end of the Eighth Five Year Plan. He asked Eydis to install an Igla passive docking system to permit docking with the station of the existing Soyuz 7K-OK as opposed to the planned 7K-S. If Chelomei's bureau could not meet this requirement, then the 'conspirator's' DOS project could be authorised in its place.

An extensive discussion of the future course of the Soviet manned space program followed. Eydis pleaded that the Almaz program not be infringed upon. If an early station was desired, completion of an Almaz could be started on 1 January. The station would not have any military systems or ECS ready, but could be modified for docking with a 7K-OK. He noted that work on Almaz had been underway since 1965, all based on the requirements of the Ministry of Defence. TsUKOS and the General Staff wanted to conduct research in reconnaissance systems - infrared, wide-spectrum, high resolution, and television transmission. Their objectives went far beyond launch of a simple space station.

Throughout these discussions Afanasyev did not praise or criticise any of the speakers. Obviously he had to formally discuss the matter with Ustinov before any decision could be made. The decisive meeting came on 26 December 1969. Ustinov called the DOS 'conspirators' to Kuibyshev Street. Mishin was sent away to Kslovodsk and Chelomei and Glushko were not invited. No one wanted to listen to any more of Glushko's diatribes about Kuznetsov's engines.

Ustinov supported presentation of the DOS concept to the Central Committee. Chelomei categorically opposed DOS and was trying to kill it through military channels. But the allure of an '18 month' station - one which would not only beat the American Skylab, but be in space in time for the 24th Party Congress - seemed too alluring. Mishin also rejected DOS, but deputies at both design bureaux supported the concept and were eager to proceed.

DOS was therefore created only when the moon project failed. Chelomei was forced to work on DOS, and it severely impacted Almaz schedules. The Salyut name was later applied to both the DOS and Almaz stations, creating the impression in the outside world that they were built by one designer. This deception was a constant weight on the heart of the designers and workers who had to accept the compromise.

The official ministry decrees starting the DOS and reorganising the Almaz projects were issued in February 1970. The co-operative DOS crash program was to build a civilian space station to beat Skylab into orbit. The civilian station (later named Salyut) would use the Almaz spaceframe fitted out with Soyuz functional equipment. Mishin's OIS military station was cancelled and Chelomei's Almaz would continue, but as second priority to the civilian station. The Soyuz 7K-S station ferry, the 7K-ST, would be revised to be a more conservative modification of the Soyuz 7K-OK. The OIS cosmonaut group was to be incorporated into the Almaz group.:

The relevant Ministry of General Machine Building (MOM) Decree 105-41 'On creation of the DOS using Almaz as a basis' was issued on 9 February, followed by Decree 57ss 'On creation of the DOS using Almaz as a basis' on 16 February. The first station was to be completed within a year. On 15 February Ustinov had conferred with the Cabinet. They agreed that work would continue on both the lunar expedition and DOS. A formal declaration from Mishin and Chelomei to work together was required.

Almaz Survives and TKS is Authorised

On 5 May 1970 Smirnov and Afanasyev settled the future course of manned spaceflight at a DOS project review. Almaz and DOS would continue in the short term, but MKBS would follow in earth orbit. Mishin's attempt to replace Almaz with his DOS-A design was defeated.

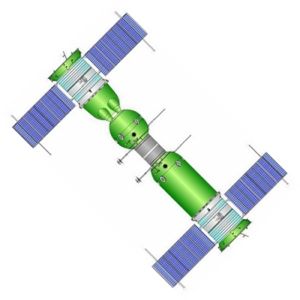

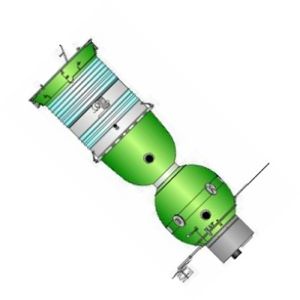

With this support Chelomei was able to obtain a formal go-ahead for development of the TKS ferry. On 16 June 1970 Decree 437-160 'On creation of the TKS and termination of the 7K-TK' was issued. The decree scheduled the first Almaz Phase 1 flights for 30 June 1972 and 2 October 1972. The crews to these phase 1 stations would be ferried by the Soyuz 7K-TK already in development. However for phase 2 the 11F72 Soyuz 7K-TK would be replaced by Chelomei’s own transport-supply spacecraft 11F72 TKS. This would consist of the 11F74 VA landing capsule (designed for the original one-launch Almaz station design), together with a new 11F77 functional-cargo block (FGB). The TKS would transport three crew and sufficient supplies for 90 days operation of the Almaz. TKS design was to be completed in fourth quarter 1972.

In parallel with DOS work Khrunichev started static, vibration, and thermal tests of the Almaz. In the second half of 1971 the first phase station design was changed from three crew to two crew. This was due to a reduction in crew size of the Soyuz 7K-T ferry crew seize after the death of the Soyuz 11 crew.

Design work began on the TKS had actually begun in 1969. To assure reliability all systems were qualification tested on dynamic, static, heat, and flammability test stands. These included complete ECS, docking, rendezvous, and electrical analogue system tests. At Zagorsk test stands were built for the payloads, engine tests, and vacuum trials. At Chkalovsk ECS and thermo-regulation system trial were conducted. Full scale stand was built for testing of the docking system as well as a full scale VA.

The Almaz DU engine unit was based on Polyot technology by Section 08-08, headed by Sergei Vladimirovich Yefimov. Development was very difficult, and when the time came for the first launch the State Commission wouldn't clear the spacecraft for launch because the engine system had not completed its test series at Zagorsk. Only when Chelomei threatened to take the matter to the Politburo was permission granted. The reliability of the system was ultimately proven on Almaz 305, which completed 760,000 engine firings.

The DU was controlled by 30 pressure data sensors and 60 temperature sensors. Dozens of radio commands were required to monitor, close, and open various elements of the system for each firing. Prior to flight the system was subjected to static, vibration, thermal vacuum, cold-soak, and flammability tests. Vibrations tests were conducted of the whole system fuelled. These took many months.

In assembly at the factory one tube was incorrectly assembled. Afanasyev and Chelomei went to the factory, and instructed that ten duplicate articles be tested in vibration and fire. These conclusively showed the incorrectly assembled element would not affect the system function. These tests included the first test of the DU in a vacuum chamber, where corrosion problems were studied in detail. Reliability, reliability was the constant refrain. Once it appeared that there was fire aboard the station; but it turned out only to be a sensor failure.

Meanwhile work on the DOS station began in February 1970 using Almaz s/n 121 and 122. The first station was shipped in February 1971 to Baikonur, where work continued to complete it day and night without break. The station was launched on 19 April 1971 as Salyut 1. The triumph turned to tragedy when the Soyuz-11 crew died due to de-pressurisation of their re-entry capsule during return to the earth after completion of a 21 day mission aboard the station.

Collaboration of the two chief designers did lead to some agreements, although these were contrary to government decrees. Chelomei was anxious to develop Almaz while Mishin wished to move on with the N1 booster to MKBS and the moon. On 3 February 1972 Mishin and Chelomei sent a joint letter to Afanasyev. They proposed that Almaz would take over the DOS role as a civilian station after the four DOS-1's had been launched. Faced for once with a show of unanimity, Afanasyev rejected the plan. He replied that under no circumstances was Almaz to be used for scientific research. On the other hand, DOS would require substantial rework to be capable of military research. Therefore, the designers were to keep to original plan:

- Complete build of 4 DOS-1 as per Decree of Central Committee and Soviet Ministers #105-41 of 9 February 1970

- Continue scientific research on DOS only

- Almaz to be resupplied by the Soyuz 7K-T developed for DOS, to be followed by the Soyuz 7K-S, developed to the TTZ specification of the Ministry of Defence

- For flight trials of the MKBS, to return from the MOK large station, use the TKS of Almaz, developed according tot he decree 437-160 of 16 June 1970

- Apollo to dock with Soyuz-M 7K-M as per decree of 14 July 1972.

Salyut 2 - Almaz Phase 1 Flight Tests Begin

Meanwhile progress toward completion of the first flight Almaz was accelerating. Initial equipment to be qualified were the STR Thermo-regulation System and SNIP Pressurisation Control System. These had to be tied into the ECS and installed in phase 1 article 4, s/n 64688, as well as the 'docked' 7K-T mock-up. For these trials two cosmonaut crews rotated shifts over a 90 day stand test. This was completed on 21 April 1972.

By June 15, 1972 the first Almaz was reaching a high level of completion and firm flight schedules could be finally be established. These were contained in Ministry of General Machine Building (MOM) Decree 'On schedule of work for the Almaz and TKS programs'. On 29 July a Proton rocket failed to place the second DOS station into orbit. Brezhnev then personally selected Almaz for the next space station launch. There was just enough time to beat the scheduled to beat the American Skylab station, scheduled for launch in April 1973. OPS-1 / Salyut 2 was delivered to Baikonur in January 1973. The first ten day flight trials of the first OPS were planned for March 1973.

Equipment delays continued to plague the project. Chelomei wrote a letter to S A Smirnov on 28 September 1972 noting systems that still needed to be delivered:

- Agat-1 + Film Camera from 16 SPKM - due 29 September 1972

- Star tracker AI-3P and Sextant P-IP by TsKB Geofizika due 15 October 1972

- Slide projector 118K by TsKB Geofizika due 15 October 1972

- VIPS-R, due 15 October 1972

Chelomei wrote to the Central Committee on 16 October 1972 and listed equipment still undelivered:

- From the Electronics Ministry: 11M02 Chemical data distributor, BKIR, BKIR-T power distribution units. 11V030 special logic unit and 11V0929

- From Ministry of Radio Industry: 11R91 Kashtan time synchroniser, 11M66 Argon digital computer

- From from Arsenal KB: 11V027 RI-P sextant and 11V028 AI-3R star tracker

On 21 November 1972 Chelomei was notified that launch would be delayed due to aircraft trials of a revised backup parachute system for the Soyuz 7K-T ferry. It was commonly believed that Mishin was intentionally delaying these tests to make Chelomei miss his schedule. The Soyuz 7K-T 11615A-8 differed in detailed equipment from the Soyuz 7K-T 11615 model used to dock with the civilian DOS stations. This included control panels for operation of Almaz electrical systems by remote control from aboard the Soyuz.

Almaz 0101-1 was delivered to Baikonur on 15 December 1972. The flight trials State Commission was established by the decree 888-303 of 27 December 1972 and was headed by Deputy Commander of the RVSN rocket forces, Col-Gen M A Grigoriev. Trials of the OPS were conducted at Chelomei’s Area 92-2 (laboratory bunker area), with electrical and integration tests at Area 92-1 (Proton MIK), prior to joining the station to the rocket. The station was also moved to Mishin’s MIK KO and MIK at Area 2B and 2 for fitting of the Igla rendezvous equipment, vacuum trials and fit checks with the Soyuz 7K-T. Full-up system tests of Almaz began in January 1973. Fuelling of the station were done back at Chelomei’s Area 91 at the 91-2 and ZNS 11G141 propellant facilities.

Preparation of Almaz for flight met fully all military requirements for radio maskirovka deception operations. The ground-based analogue OPS , 11F71-100, was readied for use by a parallel crew to mime the flight activities of Salyut 2.

Chelomei was so enraged with Mishin's delays in qualifying the Soyuz and its marginal technical characteristics that he sent a letter to the Soviet leadership on 28 February 1973. In this he complained:

- Soyuz 7K-T could not be used with Almaz because Mishin did not act according to the requirements of the decree

- The 7K-T did not have the propulsive capability for multiple docking attempts with Almaz

- The 7K-T did not have the docking equipment and necessary backups systems to guarantee crew safety in all flight modes

- The 7K-T electrical system did not have the capability to provide full function unless recharged by the OPS for 2 to 3 days after docking.

Therefore he recommended that Almaz should be unmanned (!) for Phase I flights until the TKS was available.

Chelomei's recommendations was not taken up, but it appears that Mishin did respond to pressure on the re-qualification of the Soyuz parachute system. Almaz was ready for launch on 1 March 1973 but planned launches on 5 , 15, and 25 March were scrubbed due to Mishin's Soyuz not being ready.

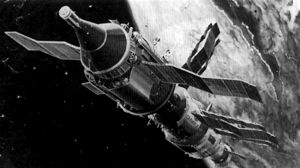

Almaz 0101-1 finally entered orbit under the cover name Salyut 2 on 3 April 1973. The first 12 days of operation were normal. Two orbital corrections were made, and the Agat camera and ASA-34 topographical/star camera were operated successfully. But before a crew could be launched the station was lost. At 12:30 Moscow time on 14 April the station moved out of tracking range. When it returned at 03:16 telemetry showed the station had de-pressurised. On 16 April at 09:12 radio communications with the station ceased.

At first the station loss was attributed to a short in electrical equipment started a fire in pressure vessel, leading to rupture of hull and de-pressurisation. This would be consistent with the fire in Salyut 1. But study of telemetry later showed that the cause was a hole in the nitrogen tank of the engine unit pressurisation system. This prevented operation of the low thrust stabilisation engines and elevated temperatures in the bay, causing loss of proper radio telemetry, de-pressurisation, and then loss of main engines. It was theorised that debris from an explosion of the third stage of the Proton booster may have penetrated the nitrogen tank. Officially it was reported that control was lost on April 25, 1973, and the OPS ceased operations on 29 April.

The same day that communications were lost with Salyut-2 the American Skylab station was rolled out to the pad. It was launched a month later and the Soviet Union lost the chance to conduct the first fully successful space station mission. Salyut 2 decayed from orbit and re-entered on 28 May 1973 in the Pacific Ocean 3000 km east of New Guinea..

Had the station continued in operation, it would have been manned by two crews: Artyukhin and Popovich aboard Soyuz 12 (back-ups Volynov, Zholobov), followed by Demin and Sarafanov (backups Rozhdestvensky and Zudov) aboard Soyuz 13.

DOS Ascendant Again - TKS VA Capsule Development Plans Changed

Following three successful Skylab missions came the shocking news that Mishin had been authorised to build a new-design fifth DOS station using Almaz facilities. Chelomei wrote a bitter letter to Afanasyev on 28 December 1973. He noted that the K-00534 TTT requirements for Almaz of the Ministry of Defence envisioned a two phase program. Instead his Khrunichev ZIKh factory was hijacked for DOS production. Now it had been further assigned to build DOS-5 for Mishin. Therefore, he concluded that the first phase of Almaz could not be completed. He asked Afanasyev how to resolve this situation.

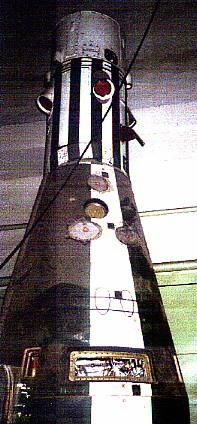

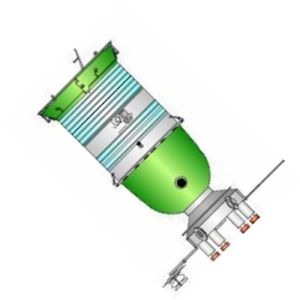

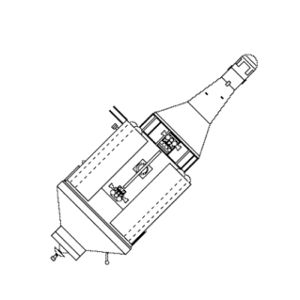

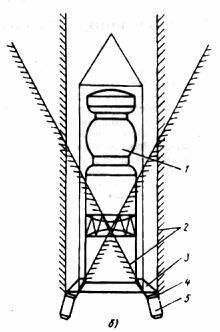

It was clear that the phased development plan for Almaz was wrecked. Therefore a decision had to be made as to how to develop the VA re-entry capsule for Almaz-2 and TKS. V A Ozertskovskiy, head of section test, defined the generic parameters for VA development. Flight trials would be necessary to develop the SAS abort system to pull the VA away from the Proton rocket in case of an emergency situation. Therefore it was suggested that one Proton launch would handle two VA's in the 82LB72 configuration. This plan was approved in 1974. Two VA's were enclosed in a cylindrical housing called the LVI. The external geometry of the 82LB2 was exactly the same as the TKS' FGB+VA. Originally two launches of two pairs of capsules were planned: VA#030 (technology article) with analogue #009 in 1975, to be followed by VA 009A with SAS and 009 analogue inside the shroud in 1976.

Fifty articles of the VA were built for development, including articles for development test stands, hatch tests, static test, and drop test, static and dynamic test, medical article #004, and those for development of the ADU rocket unit of the SAS abort system. From 1974-1977 five launches were undertaken from area 51 at Baikonur of the SAS system (three using VA #005, two using VA #007). These were attached to a complete mock-up of the FGB including the hatch tunnel and connector umbilical. When the 'Abort' command was sent, the 86 tonne thrust motor of the ADU pulled the VA capsule away from the pad. 10 seconds from the abort command the ADU/TUD/NO separated and the landing systems went into operation. The braking parachute deployed for seven seconds, followed by the main chute with 1770 square meters of area. The capsule made a soft landing 2 km away. All five tests went well.

Salyut 3 - Almaz is the First Successful Soviet Manned Space Station

Meanwhile the second Almaz was launched as Salyut 3 on 25 June 1974. Following the successful Soyuz 14 and unsuccessful Soyuz 15 missions, on 23 September 1974 the station ejected a KSI film return capsule, which was recovered damaged but with the film intact. On 25 January 1975 Salyut 3 fired its manoeuvring engines for the last time and braked itself from orbit over the Pacific Ocean.

The station had a planned life of eight months and had the special objective of locating and transmitting to the ground the co-ordinates of mobile objects at sea and in the air. For this purpose 14 type of photo cameras, and various optical sensors (pointing scope, panoramic viewer, periscope) were carried as well as infrared sensors. Semi-active radar (SAR) was not flown but was planned in the future. Salyut 3 was equipped with the Agat-1 camera, which had a 6.375 m focal length using 3 m folding optics, an OD-4 Vzor pointing scope, POU panoramic camera, as well as topographic and star cameras. In addition its Volga infrared apparatus had a 100 m resolution. The Vzor OD-4 could sight an object at sea, then train all of the sensors on that object. Skylab was visually hunted by the station using the Sokol instrument, demonstrating use of the sensor array in space-to-space warfare and reconnaissance.

Of the 17 orbits per day the station would fly, seven did not pass over the USSR and were useless for communication. To fill the gap two tracking ships were used for Salyut 3. The vessel Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was stationed off Sable Island in the Atlantic, at 51 deg N, which provided 5 to 6 orbit per day coverage. The ship Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov was stationed off Cuba, at 21 deg N, and provided coverage on 2 orbits. The result was communications opportunities on every orbit.

On 4 July 1974 Soyuz 14 docked with the Salyut 3 space station after 15 revolutions of the earth and began the first military space station mission. The planned experimental program included manned military reconnaissance of the earth's surface, assessing the fundamental value of such observations, and some supplemental medico-biological research. All objectives were successfully completed and the spacecraft was recovered on July 19, 1974 at 12:21 GMT, landing within 2 km of the aim point 140 km SE Dzhezkazgan. After the crew's return research continued in the development of the on-board systems and the principles of remote control of such a station.

In August 1974 Soyuz 15 was to conduct the second phase of manned operations aboard Salyut 3, but the Igla rendezvous system failed and no docking was made. As Chelomei had complained, Soyuz had no reserves or backup systems for repeated manual docking attempts and had to be recovered after a two-day flight. The state commission found that the Igla docking system of the Soyuz needed serious modification. This could not be completed before Salyut 3 decayed. Therefore the planned Soyuz 16 spacecraft became excess to the program (it was later flown as Soyuz 20 to a civilian Salyut station, even though over its two year rated storage life).

The Salyut 3 KSI film capsule was ejected on 23 September 1974 but suffered damage to the landing sequencer from the hot plasma sheath generated during re-entry. Therefore the heat shield did not separate, nor did the main parachute open. The capsule was deformed by the hard landing but all the film was recoverable.

On 24 January 1975 trials of a special system aboard Salyut-3 were carried out with positive results at ranges from 3000 m to 500 m. These were undoubtedly the reported tests of the on-board 23 mm Nudelmann aircraft cannon (other sources say it was a Nudelmann NR-30 30 mm gun). Cosmonauts have confirmed that a target satellite was destroyed in the test.

The next day the station was commanded to retrofire to a destructive re-entry over the Pacific Ocean. Although only one of three planned crews managed to board the station, that crew did complete the first completely successful Soviet space station flight.

Almaz Phase 2 Development

Meanwhile Phase 2 of the Almaz project continued, with the Central Committee of the Communist Party and Council of Soviet Ministers Decree 476-13 'On course of work on Almaz and the TKS' being issued on 19 January 1976. Six full-up TKS flight spacecraft were originally planned, together with nine separate unpiloted launches of the VA capsule. Two unmanned TKS flights would be followed by four manned missions (later changed to five manned flights). The decree set forth the following program for completion of Almaz Phase 1 and Phase 2:

- First quarter 1976 - Unmanned flight tests of VA capsule

- Second quarter 1976 - Completion of draft project of OPS with two docking ports for service by rotating crews

- End 1976 - Unmanned flight tests of TKS

- End 1977 - End of Phase 1 with flight of OPS-3

- End 1977 - First flight test of OPS-4 with two docking ports with return capsule on front port

- End 1978 - Manned TKS flights

- End 1980 - Acceptance into service of OPS/TKS/VA systems

However soon after this decree was issued Marshal Grechko suffered a heart attack. With this Chelomei lost his most active patron and was unable to withstand the slow strangulation of his projects by Ustinov and Glushko.

VA capsules would be tested two at a time in the special 82LB72 Proton booster configuration. The original two-launch program had been expanded to five launches of two capsules in the LVI housing. The last two launches in 1978 were to be manned. The plan was:

| Planned Date | Planned VA numbers/Mission | Actual Result |

| Nov 1976 | 009A and 009 | Cosmos 881 / 882 |

| 2nd Qtr 1977 | 009 and 009A | LV exploded |

| 4th Qtr 1977 | 102A and 102 | Cosmos 997 / 998 |

| 1978 | 008A manned / 103 | LV shutdown; LES fired. Unmanned |

| 1978 | 103A manned and dummy mass | Cosmos 1100/1001 unmanned |

The VA capsule had a hypersonic lift to drag ratio of 0.25, allowing it to generate lift during re-entry. This allowed the BSU-V manned capsule guidance system to manoeuvre the spacecraft to its landing point using the optimum path for minimal heating and G-forces. The reusable heat shield material developed for the VA was far superior to that used on the Soyuz capsule and was used as well on Chelomei’s K-1 and LKS manned spacecraft designs. The SAS system abort system for the VA separated the capsule with 15 G's of acceleration from the booster in case of a malfunction and soft landed the capsule 1.0-1.5 km from the launch pad. In the lab the 92-2 LVI mock-up was used to test automatic systems, conduct trials tests, use of the TDU engine at the centre of mass, hermetic sealing of the LVI section, and separation of the DU.

Salyut 5 - Completion of Almaz Phase 1

The second successful Almaz phase 1 flight, Salyut 5, was launched on 22 June 1976. It had taken only 60 days and 1450 man-hours to prepare Almaz 0101-2 for flight, using the services of 368 officers and 337 non-commissioned officers. The station operated for 409 days, during which the crews of Soyuz 22 and 24 visited the station. The tracking ships Academician Sergei Korolev and Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin were stationed in the Atlantic and Caribbean to provide communications when out of tracking range of the USSR.

Soyuz 23 was to have docked but its long-distance rendezvous system failed. Soyuz 25 was planned, but the mission would have been incomplete due to low orientation fuel on Salyut 5, so it was cancelled. The film capsule was recovered 22 February 1977 (and sold at Sotheby's, New York, on December 11, 1993!). The station was deorbited on 8 August 1977.

Soyuz 21 with Volynov and Zholobov aboard hard-docked with the station on 6 July 1976 after failure of the Igla system at the last stage of rendezvous. Towards end of the two month mission an early return to earth was requested due to the poor condition of flight engineer Zholobov (who was suffering from space sickness and psychological problems). The crew landed in very bad physical and mental condition 200 km SW of Kokchetav on August 25, 1976 at 18:33 GMT. It was determined that they had become emotional, not followed their physical training, and developed an unreasonable desire to return to earth. The possibility also existed that there were toxic gases in the station.

The hard-luck flights continued with Soyuz 23 on 14 October 1976. The ferry spacecraft, with Rozhdestvensky and Zudov aboard, suffered a docking system failure. Sensors indicated an incorrect lateral velocity, causing unnecessary firing of the thrusters during rendezvous. The automatic system was turned off, but no fuel remained for a manual docking by the crew of . The capsule landed in Lake Tengiz in -20 deg C conditions in a snowstorm. The wet parachute filled and dragged the capsule below the surface, cooling the capsule. Heating systems had to be turned in the capsule to conserve battery power. Amphibious vehicles attempted to recover the spacecraft but could not reach it. Finally swimmers managed to attach a cable to a helicopter. The capsule was dragged for kilometres across the icy sea. Only in the morning was the crew able to emerge from the capsule. The recovery crews were surprised they were still alive.

Soyuz 24 brought repair equipment and equipment for a change of cabin atmosphere. This special apparatus was designed to allow the entire station to be vented through the EVA airlock. Because of this the planned EVA was cancelled. However analysis after arrival showed no toxins in the air. The crew changed the cabin air anyway, then returned to earth. The mission, although a short 18 days, was characterised as busy and successful mission, accomplishing nearly as much as the earlier Soyuz 21's 50 day mission. The Soyuz was recovered February 25, 1977 9:38 GMT 37 km NE Arkalyk. The KSI film return capsule followed them a day later and was recovered successfully. It was sold at Sotheby's in 1993 and is now in the US National Air and Space Museum.

As on Salyut 3, during the flight of Salyut 5 a 'parallel crew' was aboard a duplicate station on the ground. They conducted the same operations in support of over 300 astrophysical, geophysical, technological, and medical/biological experiments. Astrophysics studies included an infrared telescope-spectrometer in the 2-15 micrometer range which also obtained solar spectra. Earth resources studies were conducted as well as Kristall, Potok, Diffuziya, Sfera, and Reatsiya technology experiments. Presumably Salyut 5 was equipped with a SAR side-looking radar for reconnaissance of land and sea targets even through cloud cover.

A third crew was to be launched to the station aboard Soyuz 25 but the flight was cancelled. It seemed that propellant reserves aboard the station had dipped too low to support another mission; in the opinion of Glushko (Mishin's successor). He therefore refused to ready another Soyuz for the mission. The spacecraft allocated for Soyuz-25 flew as Soyuz 30 to a civilian Salyut station.

This marked the end of Almaz Phase 1 and a state commission reviewed the results. The P-100 antenna demonstrated radio communications and photo television transmission of information to within 4 deg of the horizon (7 deg specification) at ranges of up to 1500 km . Photographic resolution was 15 to 20 lines/mm. The Pechora-1 television imagery transmission system worked well. All communications demonstrated, including: relay of data via Molniya-1 satellite when the station was out of sight of the USSR; automated processing of telemetry; and clear television downlink to the TsUP ground control centre and Ostankino tracking centre. Stage 1 trials were therefore declared to be successfully completed and decrees 46-13 of 19 January 1976 and 534-165 of 27 July 1996 allowed long-term use of station to proceed. Articles 104 and 105 released for use as production Almaz-2 stations.

However the overall results of the Salyut 3 and 5 flights were said to have demonstrated to the Soviet military that manned reconnaissance was not worth the expense. There was minimal time to operate the equipment after the crew took the necessary time for maintenance of station housekeeping and environmental control systems. The experiments themselves showed good results and especially the value of reconnaissance of the same location in many different spectral bands and parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. However this technology could best be exploited on unmanned satellites.

Almaz Phase 2 Tests Begin

10 December 1976 the first Proton 82LB72 VA test vehicle was placed on the pad. The VA capsules included the Probki radioactive sensor system within the Kaktus gamma ray altimeter, which set off the DU braking unit for a soft landing of the capsule. In place of space suits telemetry equipment was installed.

Launch of mission LVI-1 came at 04:00 on 15 December. At 176 seconds the ADU escape tower separated from the LVI. Once the final stage had shut down in orbit, by command from the launch vehicle sequencer, the VA 009A (also given as 009P) and its TDU separated from the LVI. Two seconds later VA 009 (or 009L) was ejected. Fifteen minutes after launch all systems of the both VA capsules were in operation. The guidance system detected the direction of flight and oriented each spacecraft for retro-fire, and the pair began the return to earth after less than one revolution. At an external atmospheric pressure of 165 mm (10 km altitude) the NO section jettisoned, the three-cupola drogue parachute ejected, and the antennae and altimeter were deployed. The Komara landing radio beacon (installed on the landing section of the parachute) was activated when the spacecraft was 1.0 to 1.5 m above the ground - which occurred at the same moment on both 009 and 009A. The Kaktus special system tripped the soft landing PRSP (parachute landing propulsion system). The soft landing was accomplished with higher accuracy than Soyuz, both capsules being recovered at 44 deg N, 73 deg E, on December 15, 1976 3:00 GMT. The flights were officially given the designations Cosmos 881 (VA 009A) and Cosmos 882 (VA 009). US intelligence believed them to be tests of recoverable manned spaceplane prototypes.

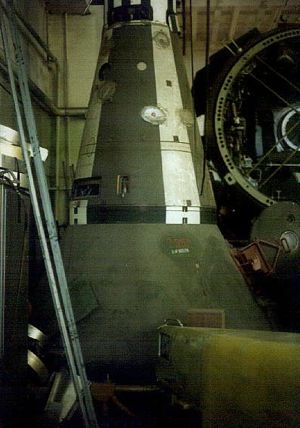

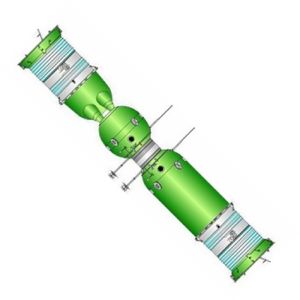

While the tests of the VA were behind schedule, the first complete TKS was delivered to Baikonur at the beginning of 1977 and launched on 17 July 1977 as Cosmos 929. The TKS manoeuvred extensively, making orbital altitude changes equivalent to a total of nearly 300 m/s of delta V. The VA capsule (serial number given as 009) returned to earth August 16, 1977. The FGB of the TKS remained in controlled flight until it was deorbited on February 2, 1978 after 201 days aloft.

The next LVI-2 VA test came a month later, on 2 August. A repeat test of the VA capsules from LVI-1 were atop the Proton (VA's 009P and 009L). However the booster failed at 49 seconds after launch. The SAS launch escape system pulled the top capsule (009P) away from the exploding Proton rocket and it was successfully recovered. The lower capsule was lost with the booster.:

Given the circumstances the plans to crew the upper VA in the next test was abandoned. LVI-3 (VA's 102P and 102L / Cosmos 997 and Cosmos 998) was launched unmanned four months behind the original schedule on 30 March 1978. Both capsules were recovered after one orbit. One source indicates that one of the capsules was 009P, on its third launch and second flight to orbit. This was said to have demonstrated the multiple re-entry capability of the heat shield and the first planned reuse of a spacecraft (Gemini 2 was refurbished and reflown as MOL-1 in the 1960's, but was not designed for that purpose).

On 15 August 1978 a VA integrity test was conducted at the large vacuum chamber at Monino with cosmonaut Sergei Vladimirovich Chelomei (son of the chief designer) suited in the capsule. At the beginning of the test a valve opened in his helmet. His suit protracted him from a deep vacuum as designed by pumping oxygen at a high rate to match the loss through the helmet. Although the chamber was repressurised barely in time, Chelomei survived the incident.

On 20 April 1979 LVI-4 VA (VA s/n 103 and s/n 008) was awaiting launch. The booster ignited, but then shut down on the pad. This triggered the launch escape system, which pulled the top capsule away from the booster. The parachute system failed and the capsule crashed to the ground. The lower capsule remained in the rocket. The top capsule was to have been manned, but the inability to demonstrate two consecutive failure-free launches of the Proton/TKS-VA combination made that (luckily) impossible.:

The launch vehicle was undamaged, and just a month later, with a switch of payload, LVI-4 was orbited as Cosmos 1100 and 1101 on 23 May 1979. The pair launched were the 102P/102L twins from LVI-3. One capsule failed when the automatic system suffered an electrical distribution failure and it did not land correctly, spending two orbits in space, while the other landed as planned after one orbit. The launch again successfully demonstrated the reusability of the VA capsule.

Almaz Phase 2 Cancelled

Chelomei felt that development of the TKS was given second priority to construction of additional DOS civilian stations by V Bugaiskiy (chief designer of NPO Mashinostroyeniya's Branch Number 1 in Fili, responsible for the FGB module). The Fili branch had developed close ties with NPO Energia and as a result of their collaboration on the DOS programme. It was only after Bugaiskiy's replacement by D Polukhin that the TKS programme was accelerated. But the damage had been done - by the time Almaz 104 would be ready for launch the TKS would still not be man-rated.

Almaz OPS-4 was originally to be built with a single docking port for the TKS. The first TKS launched to the station would also have carried life support systems that were deleted from the station, allowing the Almaz to be fitted with its own VA return capsule. The lack of a guaranteed man-rated TKS to support the planned OPS-4 flight date resulted in a last-minute revision to the station. The station would have to be capable of being supported initially by crews transported in the existing Soyuz spacecraft. Therefore the VA return capsule was deleted from OPS-4 and in its place a Soyuz docking port was built. OPS 104 would be launched with a Soyuz docking port forward and a TKS docking port aft.

But at the beginning of 1978 project funding was cut back and the first launch further delayed, meaning a crewed TKS could make the first flight after all. In December 1978 four TsKBM cosmonaut engineers were selected and began training for missions to Almaz OPS-4.

The final revised flight plan for Almaz OPS-4 was as follows:

- December 1980: Launch of Almaz-2 OPS-4

- January 1981: TKS-1: Planned first manned flight of the TKS. Crew Berezovoi, Glazkov, Makrushin. Would have docked with the Almaz OPS-4 military space station, three month duration.

- April 1981: TKS-2: Second manned TKS flight to OPS-4, four month duration. Crew Kozelsky, Artyukhin, Romanov.

- August 1981: TKS-3: Third TKS flight to OPS-4 military space station, crew Sarafanov, Preobrazhensky, Yuyukov.

- April 1982: Soyuz Almaz 4: Soyuz flight to dock with the Almaz OPS 4 space station, crew Malyshev, Laveykin.

This was the last iteration of the full-time manned Almaz program. At the end of 1978 it was decided to consolidate the Almaz and DOS projects into a single Mir space station. The existing partially-completed Almaz-2 spaceframes would be converted into man-tended automatic radar reconnaissance satellites. OPS-4 11F71 s/n 106 at that point was already in electrical tests preparatory to shipment to Baikonur. Instead it remained on the ground.

OPS-4 systems would have been similar to those of Salyut 3 and 5 (see Almaz OPS for full technical description), with the major addition of side-looking radar antennae for all weather observation of the earth’s surface and the major deletion of the Agat-1 reconnaissance camera. A range of military anti-satellite and anti-ballistic missile sensors, later flown aboard the TKS Cosmos 1686 to Salyut 7, were originally to have been ferried by TKS spacecraft to Almaz. These included an infrared telescope and the Ozon spectrometer. The TKS was also capable of refuelling the station, which required some changes to the Almaz engine system compared to the first generation models.

OPS-4 was to be equipped with the Mech-A side-looking radar. The large folded antenna array for this system was mounted on the forward cylinder of the station. The vast amounts of digital data generated by the radar would be transmitted to the ground directly or via relay satellites using the Biryuza data transmission system with the Aist antenna. The large Agat-1 optical reconnaissance system was deleted and OPS-2 was equipped only with the ASA-34 topographic camera to provide optical correlation of the ground areas imaged by the radar system. For self-defence against the American space shuttle OPS-4 was equipped with the Nudelman Shchit-2 space-to-space gun, an improved version of the weapon carried on the Almaz OPS-1 stations.

At the time of cancellation, design work had begun on OPS-5 (designated "Zvezda"), which would be equipped with docking ports for TKS vehicles at both ends of the station.

TKS Design Lives On - Almaz-T

An official resolution in February 1979 cancelled Almaz and the planned military experiments into the Mir project. Mir’s docking ports were to be reinforced to accommodate 20 tonne space station modules based on Chelomei's TKS manned ferry spacecraft in place of the lighter modules planned by Glushko. NPO Energia was made responsible for the overall space station, but subcontracted the work to Chelomei’s KB Salyut due to the press of in-house work. The subcontractor began work in the summer of 1979.

However Almaz was not completely dead. Work on an unmanned version of Almaz had already begun in 1976. The military research institute 50-TsNII-KS GUKOS conducted studies in 1976-1980 on the third generation of satellite systems., on a 10 to 15 year development cycle. Operations analysis had indicated that two automatic Almaz-T would be a necessary adjunct to Yantar and Tselina satellites. The final results of the studies were summarised in the reports 'Basic Direction of Military Space Unit Development to 1995' and 'Program for Military Space Units, 1981-1990'. Approval of these plans by the Central Committee and Soviet Ministers was issued on 2 June 1980. This covered the period through 1990 and included the Almaz-T multimode reconnaissance system. In 1981 Almaz-T was ready for flight trials, but Ustinov mothballed it. The Mech-K requirement included control of the station to within 1.5 minutes of azimuth, stabilisation of sensor to within 3 minutes of arc using gyrodynes, 10-15 g/rev, 500 kWt power.

Three automated Almaz-T were to be built from existing Almaz spaceframes (11F71-B, s/n 104 to 106; falsely designated Almaz-K or 11F667). These were given the Mech-K (Sword) code name.

Meanwhile it was still planned that two of the TKS would be flown manned to Salyut stations. In September/October 1979 three crews were formed for flights TKS-2 and TKS-3:

- TKS-2: Glazkov/Makrushin/Stepanov

- TKS-3: Sarafanov/Romanov/Preobrazhensky

- Backups: Artyukhin/Yuyukov/Berezovoi

On 20-28 November 1979 GKNII conduced state ground trials test of TKS using two crews. Many problems were uncovered requiring rework.

On April 25, 1981 TKS-1 was launched unmanned as Cosmos 1267. The VA capsule was recovered on 24 May 1981. The FGB docked with Salyut 6 on June 19 at 10:52 AM MT after 57 days of autonomous flight. It remained attached to Salyut 6 until they were both deorbited and destroyed on Salyut July 29, 1982.

Despite the success of Cosmos 1267, Ustinov was not finished with Chelomei. He cancelled the entire remaining Almaz program. A decree of 19 December 1981 halted further work on manned flights of the TKS and reoriented the flights as tests of modules for the Mir station. The TKS training group was dissolved. Work on Almaz-T was halted. Ustinov officially wanted Chelomei’s TsKBM to concentrate on ICBM development. Chelomei hid the three Almaz-T and OPS-4 space stations in a corner of his complex, labelling them as 'radioactive material'.

On 2 March 1983 TKS-2 was launched unmanned as Cosmos 1443. Aboard were 2700 kg of payload and 4000 kg of propellant. This time the VA remained attached and the TKS docked with just two days after launch. TKS-2 separated from Salyut 7 on 14 August. The VA re-entry capsule separated and the space station deorbited itself on September 19, 1983. The VA capsule continued in space for four more days, demonstrating autonomous flight, before successfully re-entering on 23 August 1983. It landed 100 km south-east of Arkalsk and returned 350 kg of material from the station.

Ustinov was old and losing his grip. Manned ‘flights’ of TKS were not completely dead. In 1982 a cosmonaut training group was formed again to fly the TKS and also to operate the military experiments aboard TKS-3 after it had docked with Salyut 7. These crews were:

- First Crew: Vasyutin, Savinykh, Volkov

- Second Crew: Aleksandrov, Saley, Viktorenko

- Backups: Solovyov, Serebrov, Moskalaneko.

Very quietly the Almaz-T project was resumed as well. It was planned that the man-tended spacecraft would be periodically visited for refuelling and repair by TKS or Soyuz and Progress spacecraft. Chelomei was finally forced to retire in October 1983. The bizarre deaths of Chelomei and Ustinov within days of each other in December 1984 opened the way for the program to be publicly resumed. A small group of cosmonauts was put into training for Soyuz flights to the man-tended Almaz-T.

Salyut 7 problems resulted in a complete breakdown of the TKS-3 plans. The first crew was bumped and instead a repair crew of Dzhanibekov and Savinykh was launched aboard Soyuz T-13 on 6 June 1985. The first ‘TKS’ crew was only completed with the launch to Salyut of Soyuz T-14 with Grechko, Vasyutin, and Volkov aboard on 17 September 1985. Grechko returned with Dzhanibekov aboard Soyuz T-13 on 26 September, clearing the aft port of Salyut for the TKS.

TKS-3 was launched unmanned as Cosmos 1686 on 27 September 1985. All VA landing systems, the ECS, seats, and manned controls had been removed and replaced with high-resolution photo apparatus and optical sensor experiments (infrared telescope and Ozon spectrometer) of the Ministry of Defence. The TKS successfully docked with Salyut 7 and remained with it for the rest of its life. For almost two months the crew of Vasyutin, Savinykh, and Volkov conducted military experiments. However Vasyutin became sick and the crew returned prematurely on 21 November 1985, leaving the station unmanned. Salyut 7 was moved to a higher orbit to await the second ‘TKS’ crew, but then control of the station was lost. There were plans to return it aboard Buran for inspection, but first flight of the spaceplane was delayed. Salyut 7 and Cosmos 1686 burned up in the atmosphere together in a fiery show over Argentina on February 7, 1991.

Almaz-T and Almaz-1V - the Last Gasp

Although Ustinov was dead, the Soviet military showed no interest in use of the Almaz-T. The Ministry of Defence was satisfied with the performance of its new electro-optical satellites. Finally the Academy of Sciences agreed to take the project over and use the first spacecraft on a science mission. A VPK decree of 12 April 1986 required Almaz 1V to be developed for international earth resources missions, including a 3 band sounder with 5 to 7 m resolution and a high-resolution scanning infrared system. The existing military Almaz-T’s would be flown as prototypes of this design.

In the second half of 1986 the first Almaz-T s/n 303 was readied for launch. General V V Favorskiy ordered it to be completed and launched with a full-up lab module in place of trials equipment. Unfortunately the Proton second stage exploded on the way to orbit on 29 November 1986.

At the beginning of 1987 it was decided not to man the Almaz-T, instead operate it in a fully automatic mode. Thus was the final Almaz cosmonaut training group disbanded.

Almaz 304 was finally launched on 25 July 1987 as Cosmos 1187. Its side-looking radar had a 20-25 m ground resolution and functioned throughout its two year service life.

Almaz 305 flew as Almaz 1 on March 31, 1991. This was the first launch of the station in post-Soviet times and the first time under its real name. :The station returned images of 10 to 15 meter resolution through 17 October 1992. The spacecraft surveyed the territory of the Soviet Union and of other countries for purposes of geology, cartography, oceanography, ecology and agriculture, and study of the ice situation at high latitudes. Almaz-1 had a 10-15 m radar ground resolution, a 10 to 30 km radiometer resolution over a 600 km swath, and an 18 month service life. Its engines completed 760,000 engine firings during that time.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, funding for the full-up Almaz-1V commercial version dried up. Attempts to interest foreign investors in the planned second generation of Almaz-1V were unsuccessful.

Thus, with a whimper, ended a 25 year program.

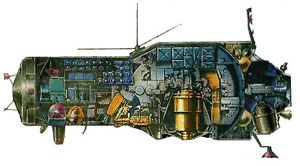

Almaz-1 Technical Description

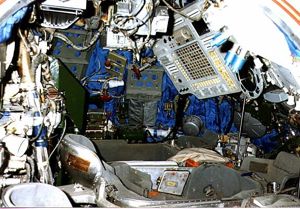

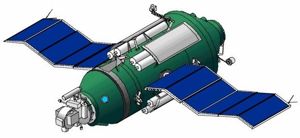

The Almaz station consisted of (from fore to aft): a 2.9 m diameter smaller diameter pressurised cylindrical section (2.9 m diameter x 3.8 m long), a conical 1.2 m long transition section, a large 4.15 m diameter x 4.1 m long cylindrical section, and a globular airlock section, with a total pressurised volume of 92.4 cu. m. The compartments of the station were, from fore to aft:

- In some variants that never flew, the VA re-entry capsule, with couches for a crew of three, and a hatch in the heat shield through which the station could be accessed

- In the variants without the VA, a short cylindrical unpressurised transition section (1.0 m long x 2.9 m diameter). Some orientation rocket engines were arranged around the periphery of this transition section. Deployable structures form extending from the top of the section formed a plume shield around each engine cluster.

- A 2.9 m diameter x 3.8 m long pressurised cylindrical section. Mounted on the outside of this section was the NR-23 self-defence gun. The interior housed:

- Work compartment, with a volume of 6.77 cu. m., housed station control equipment

- Living area, with a volume of 8.4 cu m

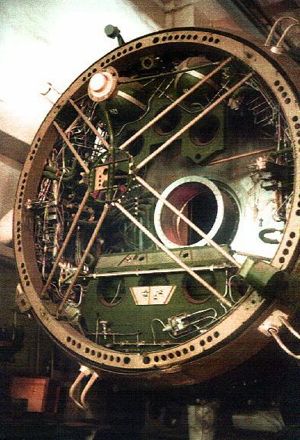

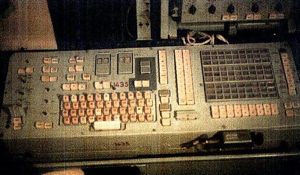

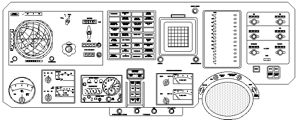

- Conical 1.2 m long transition section, housing the main station control console, including the station’s manual controls, the large POU-11 panoramic view screen for selecting targets for the other station sensors, the keyboard and printer of the BIPS encrypted teletype system, and the eyepiece of the ODU-5 sighting scope.

- The 4.15 m diameter x 4.1 m long large cylinder with the main reconnaissance apparatus had a total volume of 65.23 cu m. Most of the space was taken up by the large Agat-1 reconnaissance telescope and the Rakkord film developing system.

- The egg-shaped transit section air lock had a net volume of 7.8 cu m. The transit section had an EVA hatch on the ‘ceiling’, opposite the KSI airlock (see below). The aft hatch was equipped with a drogue apparatus of the TKS docking system. When not in use as an airlock the transit section served as the sanitation and hygiene area of the station. Around the transit section were arranged the engines of orientation and stabilisation, armatures of the thermo-regulation system, the EPU experimental pneumatic unit, and reserve air tanks for stabilisation and change of atmosphere in the station.

- The cylindrical airlock for loading and jettisoning KSI film return capsules protruded into the ‘floor’ of the section and had a total volume of 4.2 cu m. A small manipulator outside of the airlock was used to move KSI capsules from externally mounted positions on the Almaz or TKS to the airlock for film loading.

- DU engine unit. The unpressurised DU was arranged around the transit section and included two primary (3900 N thrust RD-0225) and two backup main motors for correction of orbit and manoeuvres, together with orientation engines, propellant tanks, nitrogen pressurisation tanks, and other engine system equipment. An external scientific equipment section was mounted on the outside of the DU, as were the distance measuring antennae of the Igla docking system, the Grafit command-signal antenna, and two large steer able solar panels. Within the DU were two systems umbilicals, one for use when the station was still attached to the last stage of the launch vehicle, the other for use after separation.

Weapons

- Nudelmann NR-23 23 mm (or NR-30 30 mm) cannon. This was a self-defence weapon used for defending the station against interception by American spacecraft. It was an adaptation of a standard Soviet single-barrel aircraft cannon that had been deployed since 1949. Range was from 500 to 3000 m against co-orbital targets. The NR-23 had a total mass of 39 kg. It fired a 23 mm, 200 g projectile at a muzzle velocity of 690 m/s and a rate of 950 rounds per minute. When being fired, this would have produced a recoil equivalent to 2185 N of thrust. The station was easily stabilised during firing by the two main engines of 3900 N each and the attitude control engines of 390 N each.

- Gun sight Sokol-1 (see below). The sight was used in fixed mode for gunfire operations. The entire station was moved by manual or remote control in order to track the target. Firing of the gun was controlled by the PKA Programming-Control Apparatus, which computed the lead required to destroy the target despite the 1 to 5 second transit time of the projectiles from the gun to the target.

- The Agat-1 photo apparatus by 16 SPKM was the highest-resolution device aboard. Its Kameta-11A long-focus mirror lens-objective had a 6.375 m focal length using 3 m folding optics. A multi-channel split image prism allowed the image to be fed to cameras equipped with large-format film of various types (black and white, spectrozonal, etc. ) and was also linked to Pechora television system. Detailed images would be taken after aligning the station using the OD-5 or POU-11 sighting systems.

- The OD-5 Telescope Optical System was used for wide-angle shifting magnification and was equipped with a scanning head mirror. Two magnification settings were available, one providing 2.5x – 8x magnification, the other 25x-80x. Field of view was from 32 deg to 9.5 deg (for 2.5x-8x magnification); and 3 deg to 1 deg (for 25x to 80x magnification). The camera could be pointed (in relation to the station’s long axis): +30 deg left or right; +50 deg forward to 15 deg aft. Official purposes of the camera were given as: detailed reconnaissance of areas of earth’s surface in interest of national economy and science; meteorological observations; observation of breeding grounds, forest, and steppe conditions; determination of the extent of change due to disaster (hurricane, earthquakes, man-made disaster); observation of the surface of earth.

- The POU-11 Panoramic Survey Unit allowed the sensor suite operator to observe a large area of the earth’s surface via a 340 mm diameter viewing screen. Targets of interest for the detailed sensors could be designated on the screen. The POU-11 had a magnification of 1:1 and a field of view of 60 deg.

- The Sokol-1 PKO Circular Observing Periscope. This panoramic periscope was used for observation of space and earth and for tracking space and surface targets. Magnification was from 1.5x to 6.0x with corresponding fields of view from 40 deg to 10 deg. Observation angles: horizontal to +210 deg; vertical –10 deg below to 90 deg (zenith).

- The Volga System allowed observation of the earth’s surface in the infrared range. This was the first USSR space-based infrared apparatus, with a spectral range from 3.2 to 5.2 mkm. Field of vision was 8.5 deg with a surface resolution of 100 to 120 m; Thermal resolution was 2.5 out of 20 units. Official purposes included observations in support of the national economy, hydrology, farming, forestry, and ecological monitoring.

- The Yantar-II infrared apparatus was designed for detection of explosions and other high temperature events (e.g. missile launches) in the infrared range. Two overlapping spectral ranges were available: 1.7 to 3.2 mkm and 2.5 to 3.2 mkm. Field of view was 10 deg left or right of the station, and 78 deg in azimuth.

- The ASA-34R: photographic apparatus was used for high precision topographic photography. It included the SA-34R topographic camera and the SA-33R star camera for geodesic determination of position. The camera had a 65 deg field of view and a 4 mkm positional accuracy using a 180 x 180 mm film frame format. The SA-33R cartographic apparatus was equipped with a 2:30 objective and would photograph fixed stars down to Magnitude 6.0 at the same moment the SA-34R took its image of the earth’s surface. Precision was 4 mkm using 75 x 120 mm film frame. The camera was used to map the earth and earth resources.

- The AFA-M315 / KFK-100 photo apparatus had a an objective focal length of 31/100 mm. Field of view of the imager was 100/55 deg. Resolution (lines/mm) 40/20, 50/30. Film formats 70 x 80 mm, 70 x 80 mm.

- The AI-3R 11V028 star tracker and R-1R 11V027 sextant by Arsenal KB and TsKB Geofizika were used to orient the station for photography or combat operations. They operated in 10 deg to 30 deg angles from zenith; had a magnification of 2x to 10x; could accommodate a range of angle motion of 60 grads/deg with a maximum error of 10-15 grad/sec.

- The DSI sensor of velocity of observation determined the slewing angle for use with the Agat-1 and other cameras in order to compensate image blurring.

- The Rakkord film developing system developed film from the camera systems and allowed the cosmonauts to make both contact sheets and full-size prints. The system was hermetically sealed to prevent fumes from entering the cabin atmosphere.

- The SPMK K-3 motion picture film camera was used for on-board and exterior hand-held photography

- The Zenit-YeM still camera was used for on-board and exterior hand-held photography

- The KSI capsules were used for return of developed film from the station to the earth. The capsules were placed in a cylindrical airlock with a total volume of 4.2 cu m. A small manipulator outside of the airlock was used to move additional KSI capsules from externally mounted positions on the Almaz or TKS to the airlock for film loading. The capsule was 1.35 m long and 0.85 m in diameter and came in two parts: a re-entry heat shield, and an internal payload container. Payloads of 90 cc volume and 120 kg could be accommodated. At capsule ejection the Almaz station was oriented with its nose in the direction of motion pitched down 30 deg from horizontal. As a result the capsule was pneumatically ejected at a 60 deg angle towards the earth and against the direction of motion of the station. A timer spun the capsule up, fired a solid rocket to brake the capsule for return to the earth, and then spun the capsule down. The 0.51 m long retrorocket assembly was jettisoned and the capsule entered the earth’s atmosphere. Following re-entry, it deployed a small drogue chute was deployed, and the re-entry shell separated from the payload container. The main chute followed, bringing the film to the earth. A radio beacon announced the location of the container to recovery forces

- The Pechora-1 television system was used to transmit images from the camera systems, especially the Agat-1, to the ground