Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Soyuz 7K-OK

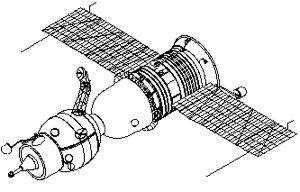

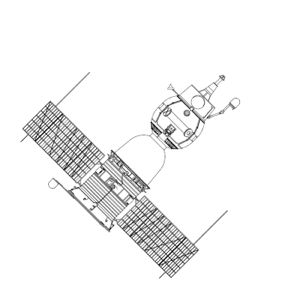

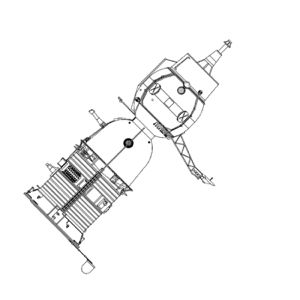

Soyuz Cutaway Cutaway of Soyuz 7K Credit: © Mark Wade |

AKA: 11F615;7K-OK. Status: Operational 1966. First Launch: 1966-11-28. Last Launch: 1970-06-01. Number: 17 . Thrust: 4.09 kN (919 lbf). Gross mass: 6,560 kg (14,460 lb). Unfuelled mass: 6,060 kg (13,360 lb). Specific impulse: 282 s. Height: 7.95 m (26.08 ft). Span: 9.80 m (32.10 ft).

The manned spacecraft became the first to complete automated orbital rendezvous, docking and crew transfer. It served as the basis for the Soyuz ferry used with the Salyut and Almaz space stations.

In the second quarter of 1963, when Korolev had begun design of the Voskhod multi-manned spacecraft, he instructed his bureau to begin design of a three-manned orbital version of the Soyuz, the 7K-OK. Korolev finally obtained approval for this spacecraft in the decree of 3 December 1963.

The 7K-OK earth-orbit version of Soyuz as developed in accordance with the decrees of 16 April 1962 and 3 December 1963 was to be capable of the following:

- Automatic rendezvous with other spacecraft

- Automatic approach and alignment

- Automatic docking

- Exit of crew into open space for transfer from spacecraft to spacecraft

- Astronavigation

- Maneuvering in orbit (changing of orbital parameters)

- Test of re-entry using body lift to modify the landing point and alleviate G-forces

- Test of the operation of radio equipment and tracking equipment

- Scientific research

The 7K Soyuz spacecraft was initially designed for rendezvous and docking operations in near earth orbit. In the definitive December 1962 Soyuz draft project, the Soyuz-A appeared as a two-place spacecraft. The Soyuz would have been launched on a lunar flyby after successive launches of 11K tanker spacecraft with a 9K translunar injection stage.

Korolev understood very well that financing for a project of this scale would only be forthcoming from the Ministry of Defense. Therefore his draft project proposed two additional modifications of the 7K: the Soyuz-P (Perekhvatchik, Interceptor) space interceptor and the Soyuz-R (Razvedki, intelligence) command-reconnaissance spacecraft. The VVS and the rocket forces supported these improved variants of the Soyuz. But Korolev had no time to work on what he considered a Soyuz 'side-line'. Therefore it was decided that OKB-1 would concentrate only on development of the Soyuz-A spacecraft, while the military projects Soyuz-P and Soyuz-R were 'subcontracted' to OKB-1 Filial number 3, based in Samara.

To Korolev's frustration, while Filial 3 received budget to develop the military Soyuz versions, his own Soyuz-A did not receive the support of the leadership for inclusion in the space program of the USSR. The 7K-9K-11K plan would have required five successful automatic dockings to succeed. This seemed impossible at the time. Instead Chelomei's LK-1 single-manned spacecraft, to be placed on a translunar trajectory in a single launch of his UR-500K rocket, was the preferred approach.

Korolev finally obtained approval for development of the 7K-OK earth orbital version of the Soyuz spacecraft in the decree of 3 December 1963.

The landing capsule could accommodate a crew of up to three. It was 2.16 m long and had a diameter of 2.2 m. On re-entry it produced a hypersonic L/D ratio of 0.2 to 0.3. It was equipped with 14 translation/orientation engines; 16 orientation engines; 6 re-entry orientation engines; 4 small correction engines; and 2 rendezvous and correction engines. The 11A511 launch vehicle designed for the spacecraft had a gross lift-off mass of 308 metric tons, was 45.6 m long, 10.3 m maximum span, and had a total burn time of 538.5 seconds. The design orbit was 205 km circular at 51.68 degrees inclination. The first flight took place on 28 November 1966 and the program was completed on 31 December 1971. Spacecraft used for space station operations had indexes 7KT.

On 25 October 1965, less than three months before his death, Korolev regained the project for manned circumlunar flight. This would use a derivative of the 7K-OK, the 7K-L1, launched by Chelomei's UR-500K, but with a Block D translunar injection stage from the N1. Originally Korolev considered that the 7K-L1, for either safety or mass reasons, could not be boosted directly by the UR-500K toward the moon. He envisioned launch of the unmanned 7K-L1 into low earth orbit, followed by launch and docking of a 7K-OK with the 7K-L1. The crew would then transfer to the L1, which would then be boosted toward the moon. This was the reason for the development of the 7K-OK.

After the death of Korolev's OKB-1 was headed by his assistant, Vasiliy Pavlovich Mishin. Kozlov considered work on his military versions of Soyuz in Samara.

In June 1965 Gemini 4 began the first American experiments in military space. In August 1965, the Soviet military ordered that urgent measures be taken to test manned military techniques in orbit at the earliest possible date. Modifications were to be made by Kozlov to the Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft for this purpose. However the first orbital launch of the 7K-OK in November 1966 a large number of failures occurred, indicating many errors in construction. The spacecraft was uncontrollable and was finally destroyed by the on-board APO destruct system.

On the second launch attempt on 14 December, the Soyuz incorrectly detected a failure of the launch vehicle at 27 minutes after an aborted launch attempt. The launch escape system activated while the vehicle was still fuelled on the pad, pulling the capsule away from the vehicle but exploding the launch vehicle and killing and injuring several people. Analysis of the failure indicated numerous problems in the escape system. In order not to inherit the problems of the 7K-OK, Kozlov's 7K-VI was completely redesigned. The final design owed little to the 7K-OK. After many twists and turns the Soyuz VI project was eventually cancelled.

As for the 7K-OK itself, after sinking to the bottom of the Aral Sea after a trouble-ridden third flight, it was taken into space by cosmonaut Komarov in April 1967. This disastrous flight ended in the cosmonaut being killed. The 7K-OK was redesigned to the extent possible and went on to accomplish 13 relatively successful manned and unmanned earth orbital flights. The 7K-OK was later modified to the space station ferry configuration 7KT with the addition of a docking tunnel. This configuration killed three cosmonauts aboard Soyuz 11 in 1971. Thereafter the spacecraft underwent a complete redesign, resulting in the substantially safer 7K-T, which flew dozens of times to Salyut and Almaz space stations until replaced by the Soyuz T in 1981.

Soyuz Guidance and Controls

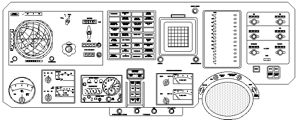

The re-entry maneuver was normally handled automatically by radio command. Spacecraft attitude in relation to the local motion along the orbit was determined by sun sensors, infrared horizon sensors and ion gauges, which could detect the spacecraft's direction of motion by the greater velocity of ions impacting the spacecraft in the direction of motion.

The cosmonaut could however take manual control of the spacecraft and manually re-enter. This was done by using the ingenious Vzor periscope device. This had a central view and eight ports arranged in a circle around the center. When the spacecraft was perfectly centered in respect to the horizon, all eight of the ports would be lit up. Alignment along the orbit was judged by getting lines on the main scope to be aligned with the landscape flowing by below. In this way, the spacecraft could be oriented correctly for the re-entry maneuver.

To decide when to re-enter, in the event of loss of communications with ground control, the cosmonaut had a little clockwork globe that showed current position over the earth. By pushing a button to the right of the globe, it would be advanced to the landing position assuming a standard re-entry at that moment.

This manual system would obviously only be used during daylight portions of the orbit. At night the dark mass of the earth could not have been lined up with the optical Vzor device. The automatic system would work day or night. However problems were found on Soyuz 1 when the ion gauges would not function in ion 'pockets' of low density in the re-entry maneuver portion of the orbit.

The Soyuz kept (to this day) the little globe and Vzor system. The Soyuz 7K-OK had no on-board inertial navigation system. To perform an orbital maneuver, the parameters for an orbital maneuver would be transmitted from the ground. When the time came for a maneuver, the spacecraft would align itself to the local vertical and direction of motion by the methods mentioned above (automatic or manual). Then three gyros would be spun up, the spacecraft maneuvered automatically or manually to the required attitude for the maneuver, and the main engine would fire automatically at the prescribed time to make the orbit change. There was a simple delta-v gauge showing the velocity change. Since the Soyuz thrust to weight was so low (around 0.06, or only half a meter per second) this meant the maneuvers could be handled manually without much error (on re-entry burns the practice was to count to five after the engine was supposed to shut off before overriding it!)

The Soyuz had a very limited maneuver capability, a source of some embarrassment during the ASTP joint flight where the Apollo did most of the maneuvering. The basic Soyuz was limited to being actively controlled for only 1 to 3 hours per day; the rest of the time was spent in a passive mode.

Crew Size: 3. Orbital Storage: 35 days. Habitable Volume: 9.00 m3. Spacecraft delta v: 390 m/s (1,270 ft/sec). Electric System: 0.50 average kW.

More at: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Family: Manned spacecraft, Space station orbit. Country: Russia. Engines: KTDU-35. Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK SA, Soyuz 7K-OK BO, Soyuz 7K-OK PAO. Flights: Soyuz 1, Soyuz 3, Soyuz 4, Soyuz 5, Soyuz 6, Soyuz 7, Soyuz 8, Soyuz 9. Launch Vehicles: R-7, Soyuz 11A511, N1, N1 1969. Propellants: Nitric acid/Hydrazine. Launch Sites: Baikonur, Baikonur LC1, Baikonur LC31. Agency: Korolev bureau, MOM. Bibliography: 121, 181, 185, 186, 187, 188, 2, 21, 23, 283, 32, 33, 36, 367, 376, 42, 474, 6, 60, 66, 82, 6899, 13125, 13126, 13127, 13128.

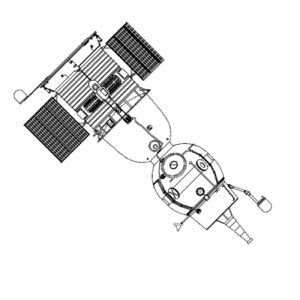

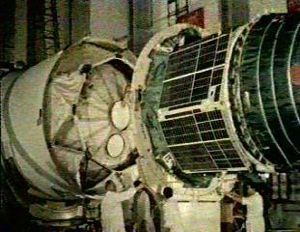

| Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Rotor Soyuz Heavily dented model of Soyuz capsule used in test of rotor recovery system. Credit: Jakob Terweij |

| Panel Soyuz 7K-OK Control panel of the initial earth orbit version of Soyuz. Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz OK panel Detail of left command panel of Soyuz OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

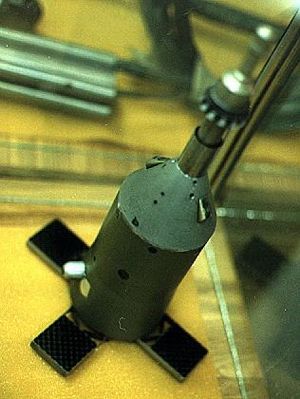

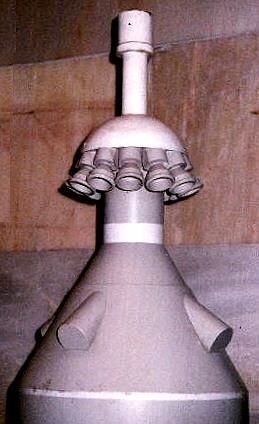

| Soyuz 7K-OK probe Soyuz 7K-OK docking probe Credit: © Mark Wade |

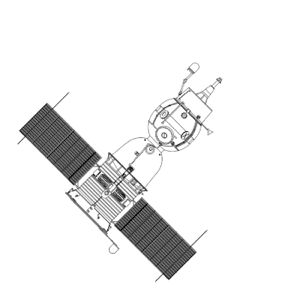

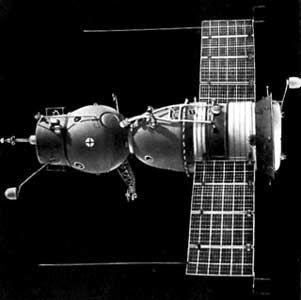

| Soyuz 4 and 5 Soyuz 4 and 5 in docked configuration Credit: © Mark Wade |

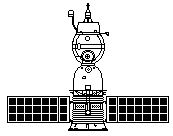

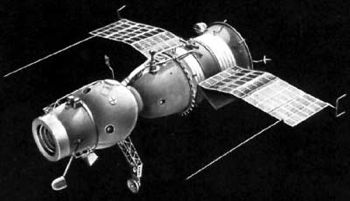

| Soyuz 7K-OK Icon Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Bottom Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Top Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz OM panel Detail of orbital module command panel of Soyuz OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Credit: © Mark Wade |

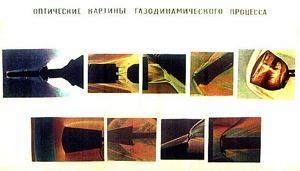

| Soyuz escape tower Soyuz launch escape system - air tunnel test model Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Gas dynamic tunnel Gas dynamic tunnel tests Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz OM interior Interior view of Soyuz 4 orbital module (through open side hatch) Credit: Andy Salmon |

| Soyuz OPS Soyuz escape tower (as used on early Soyuz launches) Credit: Andy Salmon |

| Soyuz 7K-OK Side Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz orbital module Soyuz 7K-OKS passive docking orbital module Credit: Andy Salmon |

| Soyuz control panel Soyuz orbital module control panel Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 7K-OK BO Soyuz 7K-OK Orbital Module with female docking unit Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Soyuz 1 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Soyuz 9 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Soyuz 2 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Soyuz 6 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Soyuz mated Soyuz spacecraft being mated to the booster upper stage. Credit: RKK Energia |

| Soyuz OK Panel |

1963 March 7 - . LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Soyuz 11A511.

- Korolev approves draft plan for 'Soyuz Complex' - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Chelomei,

Korolev.

Program: Lunar L1.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

Final design approval for Soyuz A spacecraft for earth orbit and circumlunar flight using orbital rendezvous, docking, and refuelling technques. Except for change of orbital module from cylindrical to spherical design, and changes to rendezvous radar tower arrangement, this design was essentially identical to the Soyuz 7K-OK that flew three years later. Additional Details: here....

1963 March 21 - . LV Family: N1. Launch Vehicle: N1 1964.

- Presidium of Inter-institution Soviet - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Chelomei,

Glushko,

Keldysh,

Korolev.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

The expert commission report on Soyuz is reviewed by the Chief Designers from 10:00 to 14:00. The primary objective of the Soyuz project is to develop the technology for docking in orbit. This will allow the spacecraft to make flights of many months duration and allow manned flyby of the moon. Using docking of 70 tonne components launched by the N1 booster will allow manned flight to the Moon, Venus, and Mars. Keldysh, Chelomei and Glushko all support the main objective of Soyuz, to obtain and perfect docking technology. But Chelomei and Glushko warn of the unknowns of the project. Korolev agrees with the assessment that not all the components of the system - the 7K, 9K, and 11K spacecraft - will fly by the end of 1964. But he does argue that the first 7K will fly in 1964, and the first manned 7K flight will come in 1965.

1963 December 3 - .

- Soyuz circumlunar spacecraft approved. - .

Nation: Russia.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

Decree 'On approval of work on the Soyuz 7K-9K-11K circumlunar complex' was issued. This elaborated on the Soyuz design made under the prior decree of 16 April 1962. Initial design work was authorised on the Soyuz 7K earth orbit basic version - capable of automatic rendezvous and docking with other spacecraft; and the 9K and 11K tanker / refuelable rocket blocks to put the 7K in high altitude or circumlunar orbits.

November 1964 - .

- No direction on space from new Soviet leadership. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bushuyev,

Korolev,

Okhapkin.

Program: Lunar L1,

Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Spacecraft: LK-1,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

After the triumph of the Voskhod-1 flight, Korolev gathers a group of his closest associates in his small office - Chertok, Bushuyev, Okhapkin, and Turkov. Firm plans do not exist yet for further manned spaceflights. Following the traditional Kremlin celebrations after the return of the Voskhod 1 crew, he has heard no more from the new political management. Khrushchev's old enthusiasm for space does not exist in the new leadership. Korolev is angry. "The Americans have unified their forces into a single thrust, and make no secret of their plans to dominate outer space. But we keep our plans secret even to ourselves. No one has agreed on our future space plans - the opinion of OKB-1 differs from that of the Minister of Defense, which differs from that of the VVS, which differs from that of the VPK. Some want us to build more Vostoks, others more Voskhods, while within this bureau our priority is to get on with the Soyuz. Brezhnev's only concern is to launch something soon, to show that space affairs will go better under his rule than Khruschev's." Korolev however does not think the new leadership will support continuation of Chelomei's parallel lunar project. Okhapkin speaks up. "Do not underestimate Chelomei. He is of the same design school as Tupolev and Myasishchev. If we give him the will and the means, his products will equal those of the Americans. Now is the right moment to combine forces with Chelomei".

1965 August 18 - .

- Soyuz development program reoriented; Soyuz 7K-OK earth orbit version to be built in lieu of Soyuz A. - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz A-1,

Soyuz A-2,

Soyuz A-3,

Soyuz A-4,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft: LK-1,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,

Soyuz V.

Military-Industrial Commission (VPK) Decree 180 'On the Order of Work on the Soyuz Complex--approval of the schedule of work for Soyuz spacecraft' was issued. It set the following schedule for the new Soyuz 7K-OK version: two spacecraft to be completed in fourth quarter 1965, two in first quarter 1966, and three in second quarter 1966. Air-drop and sea trails of the 7K-OK spacecraft are to be completed in the third and fourth quarters 1965, and first automated docking of two unmanned Soyuz spacecraft in space in the first quarter of 1966. Korolev insists the automated docking system will be completely reliable, but Kamanin wishes that the potential of the cosmonauts to accomplish a manual rendezvous and docking had been considered in the design. With this decree the mission of the first Soyuz missions has been changed from a docking with unmanned Soyuz B and V tanker spacecraft, to docking of two Soyuz A-type spacecraft. It is also evident that although nothing is official, Korolev is confident he has killed off Chelomei's LK-1 circumlunar spacecraft, and that a Soyuz variant will be launched in its place.

1965 August 28 - .

- Korolev secretly puts Voskhod production on back burner. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Gemini 5,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5,

Voskhod 6.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod,

Gemini.

It is becoming clear that in order to ever get Soyuz into space it is necessary to clear all decks at OKB-1. After Voskhod-2 the Soviet manned space plans are in confusion. The Americans have flown Gemini 5, setting a new 8-day manned space endurance record - the first time the Americans are ahead in the space race. They rubbed salt into the Soviet wound by sending astronauts Cooper and Conrad on a triumphal world tour. This American success is very painful to Korolev, and contributes to his visibly deteriorating health. In the absence of any coherent instructions from the Soviet leadership, Korolev makes a final personal decision between the competing manned spacecraft priorities. Work on completing a new series of Voskhod spacecraft and conducting experiments with artificial gravity are unofficially dropped and development and construction of the new Soyuz spacecraft is accelerated. The decision is shared only with the OKB-1 shop managers. One of Korolev's "conspirators" lays on Chertok's table the resulting new Soyuz master schedule. The upper left of the drawing has the single word "Agreed" with Korolev's signature. The only other signatures are those of Gherman Semenov, Turkov and Topol - Korolev has ordered all other signature blocks removed. Chertok is enraged. The plan provides for the production of thirteen spacecraft articles for development and qualification tests by December 1965! These include articles for thermal chamber runs, aircraft drop tests, water recovery tests, SAS abort systems tests, static and vibration tests, docking system development rigs, mock-ups for zero-G EVA tests aboard the Tu-104 flying laboratory, and a full-scale mock-up to be delivered to Sergei Darevskiy for conversion to a simulator. Chertok is enraged because the plan does not include dedicating one spaceframe to use as an 'iron bird' hot mock-up on which the electrical and avionics systems can be integrated and tested. Instead two completed Soyuz spacecraft are to be delivered to OKB-1's KIS facility in December and a third in January 1966. These will have to be used for systems integrations tests there before being shipped to Tyuratam for spaceflights.

1965 September 22 - .

- Tereshkova manoeuvres - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Feoktistov,

Korolev,

Ponomaryova,

Tereshkova.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 5.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Tereshkova confides to Kamanin that Ponomaryova is not ready for her scheduled spaceflight. Kamanin does not believe it - he has heard it from no other cosmonauts, and he has spoken to Ponomaryova often over the years. Flight plans for 1965-1966 are reviewed. The pluses and minuses of each cosmonaut in advanced training for Voskhod flights is reviewed. The latest plan for the Voskhod-3 flight is for a 20-day flight with two cosmonauts (in an attempt to upstage the planned Gemini 7 14-day flight). This is followed by another tense phone call from Korolev, then Feoktistov complaining about inadequate VVS support for the Soyuz landing system trials at Fedosiya (no Mi-6 helicopter as promised; incorrect type of sounding rockets for atmospheric profiles; insufficient data processing capacity; inadequate motor transport). When Kamanin appeals to Finogenov on the matter, he is simply told that if "Korolev is unhappy with out facilities, let him conduct his trials elsewhere". Without the support of the VVS leadership, it is up to Kamanin to try to improve the situation using only his own cajoling and contacts.

1965 October 25 - . Launch Vehicle: Proton.

- L1 manned circumlunar mission taken from Chelomei, given to Korolev. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Chelomei,

Korolev.

Spacecraft: LK-1,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Central Committee of the Communist Party and Council of Soviet Ministers Decree 'On the Concentration of Forces of Industrial Design Organisations for the Creation of Rocket-Space Complex Means for Circling the Moon--work on the UR-500K-L1 program' was issued. As a result of a presentation to the Military Industrial Commission, Afanasyev backed Korolev in wresting control of the manned circumlunar project from Chelomei. The Chelomei LK-1 circumlunar spacecraft was cancelled. In its place, Korolev would use a derivative of the Soyuz 7K-OK, the 7K-L1, launched by Chelomei's UR-500K, but with a Block D translunar injection stage from the N1. He envisioned launch of the unmanned 7K-L1 into low earth orbit, followed by launch and docking of a 7K-OK with the 7K-L1. The crew would then transfer to the L1, which would then be boosted toward the moon. This was the original reason for the development of the 7K-OK.

1965 November 24 - .

- Kamanin and Korolev - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Afanasyev, Sergei,

Korolev,

Pashkov,

Smirnov,

Tyulin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5,

Voskhod 6.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

Kamanin has his first face-to-face meeting with Korolev in 3 months - the longest delay in three years of working together. Their relationship is at low ebb. Despite having last talked about the next Voskhod flight by the end of November, Korolev now reveals that the spacecraft are still incomplete, and that he has abandoned plans to finish the last two (s/n 8 and 9), since these would overlap with planned Soyuz flights. By the first quarter of 1966 OKB-1 expects to be completing two Soyuz spacecraft per quarter, and by the end of 1966, one per month. Voskhod s/n 5, 6, and 7 will only be completed in January-February 1966. Korolev has decided to delete the artificial gravity experiment from s/n 6 and instead fly this spacecraft with two crew for a 20-day mission. The artificial gravity experiment will be moved to s/n 7. Completion of any of the Voskhods for spacewalks has been given up; future EVA experiments will be conducted from Soyuz spacecraft. Korolev says he has supported VVS leadership of manned spaceflight in conversations with Tyulin, Afanasyev, Pashkov, and Smirnov.

1965 November 30 - .

- Problems with the Igla system for Soyuz - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gagarin,

Korolev,

Mnatsakanian.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5,

Voskhod 6.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

After a meeting with Kamanin, Korolev tells Chertok in confidence that Gagarin is training for a flight on a Soyuz mission. Chertok responds that it will take him at least a year to complete training, but that doesn't matter, since Mnatsakanian's Igla docking system will not be ready than any earlier than that. Korolev explodes on hearing this. "I allowed all work on Voskhod stopped so that the staff can be completely dedicated to Soyuz. I will not allow the Soyuz schedule to slip a day further". Turkov had been completing further Voskhods only on direct orders from the VPK and on the insistence of the VVS. Aside from military experiments, further Voskhod flights were meant to take back the space endurance record from the Americans. Korolev has derailed those plans without openly telling anyone in order to get the Soyuz flying.

1965 December 4 - .

- Voskhod trainers - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gorbatko,

Popovich,

Volynov.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

At LII Kamanin reviews progress on the Voskhod trainer. It should be completed by 15 December, and Volynov and Gorbatko can then begin training for their specific mission tasks. The Volga docking trainer is also coming around. Popovich is having marital problems due to his wife's career as a pilot. Popovich will see if she can be assigned to non-flight duties.

1965 December 31 - . LV Family: N1. Launch Vehicle: N1 1964.

- Daunting year ahead - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soviet Lunar Landing,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 1.

Spacecraft: LK,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Kamanin looks ahead to the very difficult tasks scheduled for 1966. There are to be 5 to 6 Soyuz flights, the first tests of the N1 heavy booster, the first docking in space. Preparations will have to intensify for the first manned flyby of the moon in 1967, following by the planned first Soviet moon landing in 1967-1969. Kamanin does not see how it can all be done on schedule, especially without a reorganization of the management of the Soviet space program.

1966 January 6 - .

- No sign of Soviets catching up in space - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Voskhod.

Flight: Gemini 10,

Gemini 11,

Gemini 8,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod,

Gemini.

Kamanin reviews the American and Soviet space plans as known to him. In 1965 the Americans flew five manned Gemini missions, and the Soviets, a single Voskhod. In 1966, the Americans plan to accomplish the first space docking with Gemini 8, demonstrate a first-orbit rendezvous and docking with Gemini 10, demonstrate powered flight using a docked Agena booster stage with Gemini 11, and rendezvous with an enormous Pegasus satellite. Against this, the Soviets have no program, no flight schedule. Kamanin can only hope that during the year 2-3 Voskhod flights and 2-3 Soyuz flights may be conducted.

1966 January 8 - .

- Space trainers - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Mozzhorin,

Tyulin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Voskhod 3,

Voskhod 4,

Voskhod 5.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

Tyulin and Mozzhorin review space simulators at TsPK. The 3KV and Volga trainers are examined. Tyulin believes the simulators need to be finished much earlier, to be used not just to train cosmonauts, but as tools for the spacecraft engineers to work together with the cosmonauts in establishing the cabin arrangement. This was already done on the 3KV trainer, to establish the new, more rational Voskhod cockpit layout. Tyulin reveals that the female Voskhod flight now has the support of the Central Committee and Soviet Ministers. He also reveals that MOM has promised to accelerate things so that four Voskhod and five Soyuz flights will be conducted in 1966. For 1967, 14 manned flights are planned, followed by 21 in 1968, 14 in 1969, and 20 in 1970. This adds up to 80 spaceflights, each with a crew of 2 to 3 aboard. Tyulin also supports the Kamanin position on other issues - the Voskhod ECS should be tested at the VVS' IAKM or Voronin's factory, not the IMBP. The artificial gravity experiment should be removed from Voskhod and replaced by military experiments. He promises to take up these matters with Korolev.

1966 January 14 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Korolev's death - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Beregovoi,

Korolev,

Kuznetsov, Nikolai F,

Kuznetsova,

Mishin,

Petrovskiy,

Ponomaryova,

Shatalov,

Shonin,

Solovyova,

Tereshkova,

Volynov,

Yerkina.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

Korolev dies at age 59 during what was expected to be routine colon surgery in Moscow. The day began for Kamanin with firm plans finally in place for the next three Voskhod and first three Soyuz flights. Volynov and Shonin will be the crew for the first Voskhod flight, with Beregovoi and Shatalov as their back-ups. That will be followed by a female flight of 15-20 days, with the crew begin Ponomaryova and Solovyova, with their back-ups Sergeychik (nee Yerkina) and Pitskhelaura (nee Kuznetsova). Tereshkova will command the female training group. Training is to be completed by March 15. After this Kamanin goes to his dacha, only to be called by General Kuznetsov around 19:00, informing him that Korolev has died during surgery.

Kamanin does not minimise Korolev's key role in creating the Soviet space program, but believes the collectives can continue the program without him. In truth, Kamanin feels Korolev has made many errors of judgment in the last three years that have hurt the program. Mishin, Korolev's first deputy, will take over management of Korolev's projects. Kamanin feels that Mishin is a clever and cultured engineer, but he is no Korolev. Over the next three days the cosmonauts console Korolev's widow.

Korolev's surgery was done personally by Petrovskiy, the Minister of Health. Korolev was told the surgery would take only a few minutes, but after five hours on the operating table, his body could no longer endure the insult, and he passed away.

1966 January 24 - .

- New space schedules - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Afanasyev, Sergei,

Chelomei,

Korolev,

Malinovskiy,

Petrovskiy.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz,

Lunar L1.

Flight: Soviet Lunar Landing,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 1.

Spacecraft: LK,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

The VVS General Staff reviews a range of documents, authored by Korolev before his death, and supported by ministers Afanasyev and Petrovskiy. The schedules for the projects for flying around and landing on the moon are to be delayed from 1966-1967 to 1968-1969. A range of other space programs will similarly be delayed by 18 to 24 months. An institute for tests of space technology will be established at Chelomei's facility at Reutov. The IMBP will be made the lead organization for space medicine. Responsibility for space technology development will be moved from MOM to 10 other ministries. 100 million roubles have been allocated for the establishment of new research institutes. Kamanin is appalled, but Malinovskiy favours getting rid of the responsibility for these projects. The arguments over these changes - which reduce the VVS role in spaceflight - will be the subject of much of Kamanin's diary over the following weeks.

1966 February 19 - .

- Soyuz trainer - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Soyuz,

Voskhod.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

A meeting is held with the Deputy Minister of MAP, OKB-1 leaders, and 20 developers of subsystems to nail down completion of the Soyuz trainer. It was supposed to be completed by 31 March, with cosmonaut training to start 15 April. In fact OKB-1 has not even begun work on it, and they only consider it long-term work. MOM in fact has insisted that the trainers be finished early, so that they can be used as development tools by the engineers in cooperation with the cosmonauts. OKB-1 engineers don't see it that way.

1966 March 6 - .

- Soviet design bureaux reorganised and renamed. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Afanasyev, Sergei,

Mishin,

Okhapkin.

Spacecraft: LK,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Decree 'On renaming OKB-1 as TsKBEM and OKB-52 as TsKBM' was issued. In 1966 Afanasyev reorganised the military industrial complex. OKB-1 was redesignated TsKBEM. Sergei Osipovich Opakhin was made First Deputy within the new organization.

However within TsKBEM there were no relative priorities for the projects competing for resources. The R-9 and RT-2 ICBM's, the orbital, circumlunar, and lunar orbiter versions of Soyuz, the LK lunar lander, the N1 booster -- all were 'equal'. It seemed folly to be pursuing the orbital ferry version of the Soyuz when no space station had to be funded. But it was felt flying the spacecraft would solve reliability questions about the design, so it was pursued in parallel with the L1 and L3 versions.

1966 March 18 - .

- Earth-to-Space equipment for the 7K-OK, 7K-L1, and 7K-L1S - . Related Persons: Mishin, Chertok. Spacecraft: Soyuz, Soyuz 7K-L1, Soyuz 7K-L1S, Soyuz 7K-OK. Message from BE Chertok on the development of Earth-to-Space equipment for the 7K-OK, 7K-L1, and 7K-L1S' (Mishin Diaries 3-9)..

1966 March 23 - .

- Inconsistent Soviet lunar program - .

Related Persons: Mishin,

Chertok.

Spacecraft: Block D,

Soyuz,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK,

Soyuz Kontakt.

Acting director Mishin held a brainstorming session with this top managers to address "...our inconsistent lunar program". He noted then-current contradictory approaches: 1. Return to a two-launch scheme (podsadka, as baseline); 2. Keep with direct landing; 3. Use a Block D with storable propellants; 4. Use the 7K-OK as the designated return spacecraft. He noted that the L1 program was a diversion for the bureau to the core objective of landing a cosmonaut on the moon (the L3 program). Among the advantages of continuing with the L1, he noted that it "Utilizes the 7K-OK" - evidently there was no purpose for the spacecraft beyond the L1 mission in the podsadka scenario. He asks for frank opinions from his managers. V Rauschenbach noted that they "..have to do the L-1 … and therefore we will have to use a 2-launch scheme based on the L1-S". BE Chertok: discussed the rendezvous and docking systems for the various spacecraft: L1-S - "Igla"; LOK - "Kontakt" (since "Igla" cannot be used on the LOK (due to mass considerations); or a new system for the LOK. (Mishin Diaries 1-226) Here we have an indication that the L1 podsadka version did use the Igla system, which makes complete sense, since the Soyuz 7K-OK missions conducted dress rehearsals for podsadka using this system to rendezvous and dock two 7K-OK spacecraft in earth orbit.

1966 April 1 - .

- Production rates for the podsadka program. - .

Related Persons: Mishin.

Spacecraft: Block D,

Soyuz,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Ministry of Defense directive laid out the production rate for both the L1, Block D, and 7K-OK for the podsadka program. Ministry of Defense directive (Mishin Diaries 1-234) laid out the production rate for both the L1, Block D, and 7K-OK for the podsadka program:

7K-L1: one unit per month beginning 15 Sept 66

7K-OK for podsadka delivery of crews to L1: 1 unit per month beginning Oct 66

Block D deliveries: 1 unit 15 Sept; 1 unit 15 Oct; 1 further unit in October; and 1 unit per month thereafter.(Mishin Diaries 1-234)

1966 April 20 - .

- L1 accelerated program plan for 14 L1 and 6 7K-OK podsadka spacecraft. - .

Related Persons: Mishin.

Spacecraft: Soyuz,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

A VPK Military-Industrial Commission resolution on the L1 program plan was issued and included the total accelerated program for build of 14 L1 and 6 7K-OK podsadka spacecraft. The schedule:

7K-L1:

1 unit 3rd quarter 66

4 units 4th quarter 66

3 units 1st quarter 67

3 units 2nd quarter 67

3 units 3rd quarter 67

7K-OK for delivery of crews to L1:

3 units 4th quarter 66

3 units 1st quarter 67. (Mishin Diaries 1-234)

1966 April 26 - .

- Soyuz simulators - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Leonov,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Shonin,

Solovyova,

Titov,

Volynov,

Zaikin.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

The simulators and partial-task trainers continue very much behind schedule. There is talk of moving responsibility for them from Darevskiy's bureau to OKB-1. Popovich's fitness for future flight and command assignments is questionable. Nevertheless, he will join Titov, Leonov, Volynov, Shonin, Zaikin, Gagarin, and Solovyova at the Zhukovskiy Academy, from which they will be expected to graduate with advanced degrees in engineering in October 1967. Nikolayev, Bykovsky, and Gorbatko will finish one or two years later, since they will be preoccupied with flight assignments on the 7K-OK.

1966 April 27 - .

- VPK Resolution No. 101 (Mishin Diaries 1-266) mandated an aggressive L1 flight test program. - .

Related Persons: Mishin.

Spacecraft: Block D,

Soyuz,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

No 1 - August - Proton-2 (this may refer to the Proton / Block D full-mass mockup that was tested in October 1966 but then abandoned for safety reasons).

2-4: Flyby of the moon with the unpiloted version:

No 2 - October

No 3 - November

No 4 - December

No 5 - No 9: 7K-L1 flyby of the moon at intervals of one month with crew delivery by 7K-OK

No 10 - No 14: Direct flyby of the moon at one month intervals.This indicates that podsadka was the baseline approach for early missions, for both safety and launch mass considerations. Only the last five missions would be direct flights. It was probably anticipated that by then the Proton booster would be reliable enough and that improvements to the Block D and the weight reduction on the L1 would make the single-launch approach feasible. (Mishin Diaries 1-266)

1966 May 10 - .

- Voskhod 3 spiked - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Burnazyan,

Mishin,

Smirnov,

Tyulin.

Program: Voskhod,

Soyuz.

Flight: Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

A meeting of the VPK Military Industrial Commission begins with Tyulin, Mishin, Burnazyan, and Kamanin certifying the readiness for launch of Voskhod 3 on 25-28 May. Then Smirnov drops a bombshell: Voskhod 3 should be cancelled because: an 18-day flight will be nothing new; further work on Voskhod 3 will only interfere with completion of the Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft, which is to be the primary Soviet piloted spacecraft; and a new spaceflight without any manoeuvring of the spacecraft or a docking in orbit will only highlight the lead the Americans have. Kamanin argues that the long work of preparing for the flight is finally complete, and that it will set two new space records (in manned flight altitude and duration). Furthermore the flight will include important military experiments, which cannot be flown on early Soyuz flights. Smirnov and Pashkov appear not to be swayed by these arguments, but back down a bit. The State Commission for the flight may continue its work.

1966 May 15 - .

- Soyuz 7K-OK flight preparations. - . Nation: Russia. Flight: Soyuz 1, Soyuz 2A. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK. Decree 144 'On assessing preparations for flights of the 7K-OK spacecraft' was issued..

1966 June 15 - .

- Soyuz 7K-OK crew training. - . Nation: Russia. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz. Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK. OKB-1 Decree 144 'On preparation of crews ior the 7K-OK Spacecraft and civilian cosmonauts' was issued..

1966 July 2 - .

- Soyuz crew manoeuvres - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Anokhin,

Bykovsky,

Dolgopolov,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Grechko,

Khrunov,

Kolodin,

Komarov,

Makarov,

Malinovskiy,

Mishin,

Nikolayev,

Rudenko,

Smirnov,

Tsybin,

Tyulin,

Ustinov,

Volkov,

Voronov,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Kamanin is back from leave and orients himself. VVS General Rudenko has been visited by Mishin, Tsybin, and Tyulin. They want to replace Kamanin's crews for the first Soyuz mission in September-October with a crew made up of OKB-1 engineers: Dolgopolov, Yeliseyev, and Volkov as the prime crew, Anokhin, Makarov, and Grechko as back-ups. Kamanin believes this absurd proposal, made only three months before the planned flight date, shows a complete lack of understanding on the part of OKB-1 management of the training and fitness required for spaceflight. Kamanin has had eight cosmonauts (Komarov, Gorbatko, Khrunov, Bykovsky, Voronov, Kolodin, Gagarin, and Nikolayev) training for this flight since September 1965. Yet Mishin and Tyulin have been shopping this absurd proposal to Smirnov, Ustinov, and Malinovskiy, who do not know enough to reject it.

1966 July 4 - .

- Soyuz simulators - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Burnazyan,

Keldysh,

Mishin.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

The 7K-OK simulator consists of a mock-up of the BO living compartment and SA re-entry capsule only. The interiors are not yet fitted out with equipment, and development of the optical equipment to allow the cosmonauts to train with simulated dockings is proceeding very slowly. Mishin has promised a dozen times to speed up the work on the trainers, but produced nothing. Meanwhile Mishin is proceeding to train his cosmonaut team for Soyuz flights in September. It is said that he has other leaders, including Burnazyan and Keldysh, on his side.

1966 July 22 - . LV Family: N1.

- Revised L1 flight schedule is released. - .

Related Persons: Mishin.

Spacecraft: Soyuz,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

As a result of the review two days earlier (Mishin Diaries 1-266), a revised L1 flight schedule is released. No 1P - For 1M1 (N1 functional mockup) - 15 September

No 2P - 15 October & No 3P - October: Orbital flights with 2x (indecipherable) (1P, 2P and 3P were prototype L1's without heat shields and recovery possibilities).

Number 4 and 5: 2 units:Direct unpiloted flight with return to earth (November-December)

Numbers 6 to 10: 5 units: Flyby of the moon; 7K-L1 with crew transfer from 7K-OK (January to May 1967)

Numbers 11 to 14 (15): 4 units: Direct flyby of the moon by 7K-L1 (June-September) - launches every 1 to 1.5 months until completion (Mishin Diaries 1-266)

1966 July 26 - .

- Soyuz hatch problem - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Alekseyev, Semyon,

Anokhin,

Gorbatko,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Mishin,

Severin,

Sharafutdinov,

Shcheglov,

Skvortsov,

Smirnov,

Tsybin,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Yastreb.

Training of the new cosmonaut cadre is reviewed. English language courses are proving to be a particular problem. There have been some potential washouts - Sharafutdinov has done poorly in astronomy, Shcheglov suffered an injury at the beach, Skvortsov damaged his landing gear on a MiG-21 flight.

At 15:00 a major review is conducted, with Komarov, Khrunov, Gorbatko, Kamanin, and other VVS officer meeting with OKB-1 leaders Mishin, Tsybin, Severin, Alekseyev, Anokhin, and other engineers. Film is shown of the difficulties in the zero-G aircraft of cosmonauts attempting to exit from the 660 mm diameter hatch. In four sets of ten attempts, the cosmonaut was only to get out of the hatch half the time, and then only with acrobatic contortions - the inflated suit has a diameter of 650 mm, only 10 mm less than the hatch. Mishin finally concedes the point. But installation of the hatch in Soyuz s/n 3 and 4 is not possible - the spacecraft are essentially complete, and to add the hatch would delay their flight 6 to 8 months. Then Mishin makes the astounding assertion that Gorbatko and Khrunov are not adequately trained to be engineer-cosmonauts, and without this he will not allow them into space. He suggests OKB-1 engineers Anokhin and Yeliseyev instead. After outraged response, Severin finally sinks this suggestion by pointing out that no space suit has been prepared for Anokhin, and that it will take two to three months to make one. Kamanin is astounded that Mishin has pushed Anokhin all the way up to Smirnov and the VPK without even knowing he could not possibly fly due to this restriction. It again points out their poor management. Finally Mishin agrees that spacecraft s/n 5 and 6 and on will have 720 mm hatches. The ECS for the suits for those missions will have to be changed from a backpack configuration, with the equipment rearranged around the waist of the cosmonaut. The crews for the flight will be an experienced VVS pilot cosmonaut as commander, and (Kamanin realizes he may have to concede) a VVS engineer as flight engineer cosmonaut. They will have to complete training by 1 October 1966.

1966 July 30 - .

- Beregovoi pushed for Soyuz mission - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Anokhin,

Beregovoi,

Burnazyan,

Gagarin,

Keldysh,

Khrunov,

Krylov,

Malinovskiy,

Mishin,

Rudenko,

Shonin,

Tsybin,

Tyulin,

Vershinin,

Volynov,

Zakharov.

Program: Soyuz,

Voskhod.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Yastreb.

Mishin, Rudenko, and others have met with Beregovoi and support his selection as commander for the first Soyuz mission. Kamanin does not believe he is fit for the assignment, due to his age, his height and weight (that are the limit of the acceptable for the Soyuz). Gagarin reports that during a visit to OKB-1 the day before, he discovered that they were still going all out to prepare their own crews and train their own cosmonauts for Soyuz flights. Kamanin reassures him that the full power of the VVS, the General Staff, and the Ministry of Defence is behind the position that only VVS pilots will command the missions. Mishin is gloating over the latest spacesuit tests. Khrunov tried exiting from the Soyuz hatch in the Tu-104 zero-G aircraft. Using his full dexterity and strength, he had more success than in earlier tests. But Kamanin notes that designing a spacecraft hatch only 10 mm wider than the cosmonaut is hardly the basis for practical spaceflight or training. Later Kamanin plays tennis with Volynov and Shonin. Their Voskhod 3 flight is still not officially cancelled. They have been fully trained for the flight for months now, but no go-ahead is given. On Saturday, Tsybin presents to the General Staff OKB-1's concept for training of engineer cosmonauts. Tyulin, Burnazyan, and Keldysh have approved the plan, except they have substituted VVS engineer cosmonauts for those from OKB-1 for the first Soyuz flights. So this is the result of months of controversy - a position that there is no fundamental opposition to cosmonaut candidates from OKB-1. Kamanin sees the absolute need for his draft letter to be sent from the four Marshals (Malinovskiy, Zakharov, Krylov, and Vershinin) to the Central Committee. Mishin continues to "assist" the situation - it has been two weeks since he promised to submit the names and documentation for his candidates to the VVS, and he has done nothing.

1966 August 3 - .

- Sea tests of Soyuz - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Anokhin,

Brezhnev,

Gagarin,

Kubasov,

Mishin,

Smirnov,

Ustinov,

Volkov,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Mishin sends a letter to Kamanin, linking acceptance of his eight cosmonaut candidates from OKB-1 to continuation of sea recovery tests of the Soyuz capsule at Fedosiya. Kamanin's early hopes for Mishin have been dashed - not only is he no Korolev, but his erratic management style and constant attempts to work outside of accepted channels and methods, are ruining the space program. Later Gagarin briefs Kamanin on the impossibility of meeting Brezhnev, who has flown south for vacation without reacting to Gagarin's letter. Most likely, the letter will be referred to Ustinov, who will pass it to Smirnov, with instructions to suppress this "revolt of the military". Gagarin requests permission to resume flight and parachute training in preparation for a space mission assignment. Kamanin agrees to allow him to begin three months before the mission to space. This will be no earlier than 1967, as Gagarin will not be assigned to the first Soyuz flights.

Kamanin decides to smooth over matters with OKB-1. He calls Mishin, and then Tsybin, and agrees to begin processing of Anokhin, Yeliseyev, Volkov, and Kubasov as soon as he receives their personnel files and security clearances. Mishin promises to deliver the Soyuz mock-up of the Tu-104 zero-G aircraft soon - it slid from 20 July, then from 7 August.

1966 August 5 - .

- Showdown on spacesuits - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Alekseyev, Semyon,

Anokhin,

Bushuyev,

Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Litvinov,

Mishin,

Nikolayev,

Severin,

Tsybin,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Yastreb.

At a meeting at LII MAP Zazakov, Litvinov, Mishin, Tsybin, Bushuev, Severin, Alekseyev, and Komarov spar over the hatch and spacesuit problem. Severin only agrees to modifying the ECS under immense pressure, but the modified suit will not be ready until November. Severin could not get Mishin to agree to an increased hatch diameter from Soyuz s/n 8 - Mishin will only "study the problem". An arrangement of the ECS around the waist of the cosmonaut is finally agreed. Mishin and Litvinov categorically rejected any modification of the hatch in the first production run of Soyuz.

In turn, Factory 918 insisted on a final decision on Soyuz crews. They cannot build 16 of the custom-built spacesuits for all possible candidates for the flights (8 from VVS and 8 from OKB-1). It was therefore agreed that the commanders of the first two missions would be Komarov and Bykovsky, with Nikolayev and Gagarin as their backups. It was finally decided to assume that the other crew members would be either Khrunov and Gorbatko from the VVS, or Anokhin and Yeliseyev from OKB-1.

1966 August 10 - .

- Soyuz schedule has been delayed again - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Demin,

Gagarin,

Mishin,

Tereshkova,

Tyulin.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Soyuz s/n 5/6.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Soyuz s/n 1 and 2 will be flown unpiloted by October 1966 Manned flights aboard Soyuz s/n 3, 4, 5, 6 will not take place until the first quarter of 1967. Later Mishin tours the cosmonaut training centre - the first time in his life he has visited the place. Mishin admires the new construction from Demin's balcony on the 11th floor of cosmonaut dormitory, then goes to Tereshkova's apartment on the seventh floor, and then Gagarin's apartment. Mishin insists on drinking a toast of cognac on each visit. Tyulin reveals this is a peace mission - they want to normalize relations and get on with cosmonaut training. At Fedosiya the auxiliary parachute of a Soyuz capsule failed to open during a drop test. Kamanin believes that the Soyuz parachute system is even worse than that of Vostok. His overall impression of the Soyuz is poor: the entire spacecraft looks unimpressive. The small dimensions of hatch, antiquated communication equipment, and inadequate emergency recovery systems are only the most noticeable of many discrepancies. If the automatic docking system does not function, then the entire Soviet space program will collapse in failure.

1966 August 23 - .

- Soyuz recovery training at sea - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Afanasyev, Sergei,

Burnazyan,

Bykovsky,

Gorbatko,

Grechko,

Keldysh,

Khrunov,

Kolodin,

Komarov,

Kubasov,

Nikolayev,

Smirnov,

Volkov,

Voronov.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Yastreb.

Nikolayev, Bykovsky, Komarov, Khrunov, Gorbatko, Kolodin, and Voronov complete two parachute jumps each, with landing at sea. Training in sea-recovery by helicopter, with the cosmonauts in spacesuits, will be completed over the next two days. Smirnov is ready to sign a letter from Afanasyev, Burnazyan and Keldysh creating a new civilian cosmonaut training centre under the Ministry of Medium Machine Building, separate from the VVS centre. The letter is not coordinated with the Defence Ministry, and contradicts the letter sent by the four marshals to the Central Committee. Kamanin prepares a vigorous refutation of the letter's position. The physicians' board on OKB-1 candidates has only cleared Yeliseyev for flight - they could not agree on Volkov, Kubasov, and Grechko. OKB-1 only submitted four candidates for review, not the eight promised.

September 1966 - .

- N1 two-launch moon scenario proposed - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bushuyev,

Korolev.

Program: Lunar L3,

Lunar L1,

Soyuz.

Spacecraft: LK,

Molniya-1,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Bushuyev proposed a two launch variation on Korolev's single-launch scheme. The increased-payload version of the N1 with six additional engines was not planned to fly until vehicle 3L. 1L and 2L were to be technology articles for ground test with only the original 24 engine configuration. At that time the first Apollo test flight was planned by the end of 1966, and the US moon landing no later than 1969. The Soviets expected the first test of their LK lander in 1969, and concluded they could not expect to land a Soviet man on the moon until 1972. Additional Details: here....

1966 September 2 - .

- Cosmonaut civilian program training groups - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Dobrovolsky,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Khrunov,

Kolodin,

Komarov,

Leonov,

Nikolayev,

Shatalov,

Volynov,

Voronov,

Zholobov.

Program: Soyuz,

Lunar L1,

Lunar L3.

Flight: Soviet Lunar Landing,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 1,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 2,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 3,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Soyuz s/n 5/6,

Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft: LK,

Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Kamanin organises the cosmonauts into the following training groups:

- Soyuz 7K-OK: Gagarin, Komarov, Nikolayev, Bykovsky, Khrunov, Gorbatko, Voronov, Kolodin

- L1: Volynov, Dobrovolskiy, Voronov, Kolodin, Zholobov, Komarov, Bykovskiy

- L3: Leonov, Gorbatko, Khrunov, Gagarin, Nikolayev, Shatalov

Rudenko agrees with Kamanin's plan, except he urges him to assign more cosmonauts to the Soyuz 7K-OK group, and include OKB-1 cosmonauts in the 7K-OK, L1, and L3 groups, and Academy of Science cosmonauts in the L1 and L3 groups.

These cosmonaut assignments were in constant flux, and many cosmonauts were assigned to train for more than one program - resulting in multiple claims in later years that 'I was being trained for the first moon flight'.

1966 September 21 - .

- Soyuz simulators still incomplete - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Darevskiy,

Tsybin.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Darevskiy now reports that the 7K-OK will not be finished until the end of October at the earliest. Poor quality optic systems and unreliable equipment from OKB-1 are blamed. Tsybin promises to resolve all issues, with OKB-1-providing equipment within a week

1966 September 29 - .

- Cosmonaut leave cancelled to support Soyuz missions in December - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gagarin,

Mishin.

Program: Soyuz.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Mishin claims he will be ready to fly two piloted 7K-OK spacecraft in the second-half of December 1966. No one but Mishin believes this is possible. The tests of many subsystems are not finished, with the parachutes and ECS far from completion of qualification tests. However in order not to give Mishin any excuses, Kamanin orders Gagarin to cancel all cosmonaut leave for the rest of the year, and to accelerate training to be ready for Soyuz flights by 1 December.

1966 November 3 - .

- Soyuz parachute fails in drop test. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gorbatko,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Mishin,

Tyulin.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

In a test of the reserve parachute at Fedosiya, the Soyuz capsule was dropped from the aircraft at 10,500 m. The drogue chute deployed normally, as did the main parachute. They were then jettisoned and the reserve parachute deployed normally. However descent on both main and auxiliary chutes occurs only with noticeable pulsations of their cupolas, with the capsule revolving at one RPM. In this case it finally led to failure of the lines of the reserve chute at 1500 m, after which it crashed to earth. Contributing to the problem was the jettison of the remaining hydrogen peroxide reaction control system fuel from the capsule during the descent. It is normally expected that 30 kg of the 70 kg load of propellant will remain after re-entry. When this was vented, it burned the parachute lines. Each line will normally carry a load of 450 kg, but after being burnt by the peroxide, they can be torn apart by hand. Meanwhile there is still no agreement on crew composition. Komarov, Bykovsky, Khrunov and Gorbatko can be ready for flight by10 December. However the VPK representatives, Tyulin and Mishin insist that their OKB-1 candidates be flown in stead of Khrunov and Gorbatko.

1966 November 11 - .

- Soyuz crew dispute drags on - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Kubasov,

Makarov,

Mishin,

Volkov,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Kamanin visits OKB-1. Mishin certifies that unmanned Soyuz s/n 1 and 2 will fly by 26 November, and the manned spacecraft s/n 3 and 4 by the end of December. The departure of cosmonauts for the range must take place not later than 12-15 December. There remains only 30 days for training of the crews, the member of which have still have not been agreed. Mishin ignores common sense and still insists on the preparation of only his own engineers (Yeliseyev, Kubasov, Volkov, Makarov). The argument over the Soyuz crews continues without resolution up to the Central Committee level, then back down through the VPK and State Commission, over the next week.

1966 November 18 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- N1 facilities tour - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Kubasov,

Mishin,

Nikolayev,

Rudenko,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Rudenko and Kamanin meet with Mishin at Area 31 (18-20 kilometers east of Area 2). Launch preparations are reviewed, and Mishin satisfies them that the two Soyuz will be launched on 26-27 November. The State Commission will meet officially tomorrow at 16:00. For today, they tour the N1 horizontal assembly building at Area 13. Korolev planned the N1 as early as 1960-1961. It will have a takeoff mass of 2700-3000 tonnes and will be able to orbit 90-110 tonnes. The first stage of rocket has 30 engines, and the booster's overall height is114 m. The construction of the assembly plant, considered a branch of the Kuibyshev factory, began in 1963 but is still not finished. Two factory shops are in use, and the adjacent main assembly hall is truly impressive - more than 100 m in length, 60 m high, and 200 wide. Work on assembly of the ground test version of the rocket is underway. Assembly will be completed in 1967, and it will be used to test the systems for transport to the pad, erection of the booster, servicing, and launch preparations. The booster is to be ready for manned lunar launches in 1968. The construction site of the N1 launch pads occupies more than one square kilometre. Two pads are located 500 meter from each other. Between and around them is a mutli-storied underground city with hundreds of rooms and special equipment installations.

Only late in the night Rudenko and Mishin finally agree that the crews for the first manned Soyuz flights will be: Basic crews: Komarov, Bykovsky, Khrunov, Yeliseyev; Back-up crews: Gagarin, Nikolayev, Gorbatko, Kubasov. Meanwhile poor weather in Moscow is delaying zero-G training for the flight. In the last week only one weightless flight on the Tu-104 was possible - and a minimum of 24 flights need to be flown before the launch. It was therefore decided to ferry one Tu-104 to Tyuratam and train the cosmonauts here - it made its first flight today.

1966 November 19 - .

- First Soyuz Launch Commission - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Afanasyev, Sergei,

Grechko,

Keldysh,

Kerimov,

Krylov,

Kurushin,

Malinovskiy,

Mishin,

Mnatsakanian,

Pashkov,

Petrovskiy,

Pravetskiy,

Rudenko,

Ryazanskiy,

Serbin,

Smirnov,

Tkachev,

Ustinov,

Vershinin,

Zakharov.

Program: Soyuz,

Lunar L1,

Lunar L3.

Flight: Soviet Lunar Landing,

Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 1,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 2,

Soyuz 7K-L1 mission 3.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

Rudenko has reached agreement with Mishin that L1 and L3 crews will also consist of a VVS pilot as commander, and an OKB-1 flight engineer. Kamanin is depressed. Despite the support six marshals (Malinovskiy, Grechko, Zakharov, Krylov, Vershinin and Rudenko), Mishin has won this argument with the support of Ustinov, Serbin, Smirnov, Pashkov, Keldysh, Afanasyev, and Petrovskiy. Later the State Commission meets, for the first time in a long time at Tyuratam. Kerimov chairs the session, with more than 100 attendees, including Mishin, Rudenko, Krylov, Pravetskiy, Kurushin, Ryazanskiy, Mnatsakanian, and Tkachev. All is certified ready,. Launch of the active spacecraft is set for 26 November, and the passive vehicle on 27 November.

1966 November 20 - .

- Soyuz first flight plan - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Feoktistov,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Pravetskiy,

Rudenko,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Yastreb.

Feoktistov briefs the State Commission on the flight plan for the upcoming mission at 10:00. Each spacecraft will be in space for four days, and will demonstrate orbital manoeuvre, rendezvous and automatic spacecraft docking. If the passive vehicle can be placed in orbit within 20 kilometres of the previously launched active spacecraft, then docking can be accomplished on the first or second orbit of passive vehicle. If they are more than 20 kilometres apart, then 24 hours will be needed to manoeuvre the spacecraft to a rendezvous. Kamanin and Rudenko take a zero-G flight aboard the Tu-104 (Pravetskiy was bumped at the airfield "due to space limitations"). The Tu-104 needs good visibility of the horizon in order to fly the zero-G parabola. The aircraft is accelerated to maximum speed and then pulls up into a sharp climb (going from 7,000 to 10,000 m). At the end of the climb 20-25 seconds of weightlessness is available for training the cosmonauts. Komarov, Bykovsky, Khrunov and Yeliseyev are aboard today. Khrunov practiced moving from the BO living module of the passive vehicle to that of the active spacecraft. Yeliseyev practiced exiting and entering the BO hatches with his bulky spacesuit and 50- kilogram ECS system strapped to his leg.

Mishin receives an encrypted telegram from Okhapkin and Tsybin. They propose that one of the cosmonauts on the first mission will back away from the docked spacecraft on a 10-m long safety line and film the other cosmonaut moving from one spacecraft to the other. Kamanin believes only Khrunov (with more than 50 Tu-104 weightless flights), has enough training to accomplish the task. After a sauna with Rudenko and an attempt to watch a film (aborted due to projector failure), Kamanin takes a walk in a drizzly, evocative night. He visits the cottages used by Korolev and the cosmonauts for the first missions. A light burns in Korolev's cottage - Mishin is working late. Kamanin recalls his many confrontations with Korolev, but also remembers how well he managed people compared to Mishin. Even if he had already decided personally what to do, he took the time to listen to other opinions and everyone felt their views had been considered.

1966 November 21 - .

- Soyuz crews agreed officially - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Anokhin,

Bykovsky,

Feoktistov,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Kamanin,

Kerimov,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Kubasov,

Mishin,

Nikolayev,

Rudenko,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-L1,

Soyuz 7K-LOK,

Soyuz 7K-OK.

The weather continues to deteriorate, and Kamanin considers moving the Tu-104 and cosmonauts to Krasnovodsk in order to get the 24 necessary zero-G flights before launch. At 11:00 the State Commission meets at Area 31. Present are Kerimov, Mishin, Rudenko, Kamanin, Komarov, Bykovsky, Khrunov, Yeliseyev, Anokhin and others. Mishin describes the status of preparations of Soyuz s/n 1, 2, 3, 4 for launch. He notes that the L1 and L3 lunar spacecraft are derived from the 7K-OK, and that these flights will prove the spacecraft technology as well as the rendezvous and docking techniques necessary for subsequent manned lunar missions. Feoktistov and the OKB-1 engineers say a launch cannot occur before 15 January, but Mishin insists on 25 December. That will leave only 20 days for cosmonaut training for the mission, including the spacewalk to 10 m away from the docked spacecraft. Faced with the necessity for the crews to train together as a team prior to flight, Mishin at long last officially agrees to the crew composition for the flights: Komarov, Bykovsky, Khrunov, and Yeliseyev as prime crews, with Gagarin, Nikolayev, Gorbatko, and Kubasov as back-ups. However a new obstacle appears. KGB Colonel Dushin reports that Yeliseyev goes by his mother's surname. His father, Stanislav Adamovich Kureytis , was a Lithuanian sentenced to five years in 1935 for anti-Soviet agitation. He currently works in Moscow as Chief of the laboratory of the Central Scientific Research Institute of the Shoe Industry. Furthermore Yeliseyev had a daughter in 1960, but subsequently annulled the marriage in 1966.

Later Feoktistov works with the crews on spacecraft s/n 1 to determine the feasibility of the 10-m EVA. The cosmonauts suggest a telescoping pole rather than a line be used to enable the cosmonaut to be in position to film the joined spacecraft. Bushuyev is tasked with developing the new hardware.

1966 November 24 - .

- Apollo program delays give Soviets opportunity to leapfrog Americans - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Khrunov,

Komarov,

Yeliseyev.

Program: Soyuz,

Voskhod.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A,

Soyuz s/n 3/4,

Soyuz s/n 5/6,

Soyuz s/n 7,

Voskhod 3.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Voskhod.

Komarov, Bykovsky, Khrunov, and Yeliseyev have completed zero-G training in the Tu-104 at Tyuratam, and need to get back to Moscow to complete simulator training. But continued bad weather at Moscow means that they will have to be flown by Il-14 to Gorkiy, and then get to Moscow by train. Kamanin notes reports on NASA's reorganised flight program for the Apollo program. Under the new schedule, the first attempt at a manned lunar landing will be possible in the first half of 1968. The first manned flight of the Apollo CSM has slipped from December 1966 to the first quarter of 1967. This makes it possible that the Soviets can make 3 to 5 manned spaceflights before the first Apollo flight - the flights of Soyuz s/n 3 and 4 in December 1966, Voskhod 3 in January 1967, and Soyuz s/n 3 and 4 in February 1967.

1966 November 25 - .

- Soyuz launch commission - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Belousov,

Gagarin,

Gorbatko,

Kolodin,

Mishin,

Nikolayev.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK,

Yastreb.

Gagarin, Nikolayev, Gorbatko, Kolodin and Belousov arrive at Tyuratam for Tu-104 zero-G training, while the prime crews successfully arrive at Moscow for simulator training. The State Commission meets. After extensive detailed reports, Mishin certifies that the boosters and spacecraft at 09:00 on 26 November. S/N 2 would be launched first, on 28 November at 14:00, followed by s/n 2 24 hours later. The go-ahead is given for launch. In zero-G tests, the reserve cosmonauts find it is necessary to grip the handrail from above with both hands to move easily with the ECS strapped to the leg. The previously approved method, with one hand on top, the other below the handrail, was only good with the ECS configured as a backpack. The hardest part of the EVA will be getting on the spacesuits beforehand, especially in achieving a seal between the gloves and the suit

1966 November 26 - .

- Soyuz vehicles rolled out to pads for dual launch - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Mishin,

Rudenko,

Vershinin.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

The boosters were rolled out to the pads over eight hours late, at 17:30. There were delays in integrating the spacecraft in its fairing with the rocket, due to the much greater length of the Soyuz fairing and SAS abort tower (making the whole vehicle 46 m long). There was even concern that the assembled rocket would topple over in its horizontal carriage due to the forward centre of gravity. Mishin is getting out of control - publicly screaming at his staff. He demeans the competence of the cosmonauts and extols the quality of his own engineer-cosmonauts in front of the leadership. He yet again insists on crew changes. Kamanin discusses Mishin's public hysterics and tantrums with Rudenko. Rudenko agrees that the man is unstable and unsuitable, but says that he has powerful forces behind him on the Central Committee and Council of Ministers. No one except Vershinin dares oppose him. Rudenko's only course is to let the State Commission and government decide who will fly.

1966 November 28 - .

- Cosmos 133 - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Belyayev,

Gagarin,

Kerimov,

Mishin,

Nikolayev,

Rudenko,

Yegorov.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Four years behind Korolev's original promised schedule, the countdown is underway for the first Soyuz spacecraft. A new closed circuit television system allows the rocket to be observed from several angles during the final minutes. Mishin, as per tradition, personally stays with the rocket until the last moment. Rudenko, Kerimov, and Kamanin observe the launch from the bunker, while Gagarin, Nikolayev, Belyayev and Yegorov observe from the observation post. The launch is perfect, within 0.2 seconds of the 16:00 launch time. The separation of the first stage strap-ons can be seen with the naked eye in the clear sky. The spacecraft is given the cover designation Cosmos 133 after launch. By 22:00 the spacecraft is in deep trouble. For unknown reasons the spacecraft consumed its entire load of propellant for the DPO approach and orientation thrusters within a 15-minute period, leaving the spacecraft in a 2 rpm spin. At the insertion orbital perigee of 179 kilometres, the spacecraft will have a life of only 39 orbits. It is decided to attempt to stop the spin on the 13th orbit using other thrusters and the ion flow sensors to determine attitude. Then the re-entry sequence will be commanded on the 16th orbit, with the spacecraft to use solar sensors to orient itself for retrofire on the 17th orbit.

1966 November 28 - . 11:00 GMT - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC31. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Soyuz 11A511.

- Cosmos 133 - .

Payload: Soyuz 7K-OK (A) s/n 2. Mass: 6,450 kg (14,210 lb). Nation: Russia.

Agency: MOM.

Program: Soyuz.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

Duration: 1.97 days. Decay Date: 1966-11-30 . USAF Sat Cat: 2601 . COSPAR: 1966-107A. Apogee: 219 km (136 mi). Perigee: 173 km (107 mi). Inclination: 51.80 deg. Period: 88.40 min.

First test flight of Soyuz 7K-OK earth orbit spacecraft. A planned 'all up' test, with a second Soyuz to be launched the following day and automatically dock with Kosmos 133. This was to be followed by a manned link-up in December 1966. However Kosmos 133's attitude control system malfunctioned, resulting in rapid consumption of orientation fuel, leaving it spinning at 2 rpm. After heroic efforts by ground control and five attempts at retrofire over two days, the craft was finally brought down for a landing on its 33rd revolution. However due to the inaccuracy of the reentry burn, it was determined that the capsule would land in China. The APO self destruct system detected the course deviation and the destruct charge of several dozen kilogrammes of explosive was thought to have destroyed the ship on November 30, 1966 at 10:21 GMT. But stories persisted over the years of the Chinese having a Soyuz capsule in their possession....

1966 November 29 - .

- Cosmos 133 fails to land on first attempt - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.

At 10:00 the re-entry command sequence is transmitted, but there is some doubt if the sequence was correct. Mishin decides to abort the landing attempt. Later telemetry shows that the command sequence was indeed correct. Attempts are made on orbits 18 and 19 to orient the spacecraft using data from the ion flow sensors, but these were not successful. After orbit 20 the spacecraft's orbital track no longer passed over Soviet ground stations, and another attempt for a solar-oriented re-entry would have to wait for orbit 32. But the spacecraft would possibly decay out of orbit before that time. Commands were transmitted to the spacecraft to raise its orbit, but from orbits 20 to 29 there was no tracking that allowed verification if the manoeuvres had been made. After an uncertain night, telemetry was received in the morning that showed the spacecraft had accepted all three commands for firing of the engines using the ion flow sensors for orientation. However on the first manoeuvre, the engines cut off after 10 seconds, after 13 seconds on the second, and 20 seconds on the third. In all three cases the spacecraft became unstable as soon as the engine firing began, developing large angular oscillations, which resulted in the engines being automatically shut down prior to delivering the total planned total impulse.

1966 November 30 - .

- Cosmos 133 lost on re-entry - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Soyuz.

Flight: Soyuz 1,

Soyuz 2A.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-OK.