Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Apollo

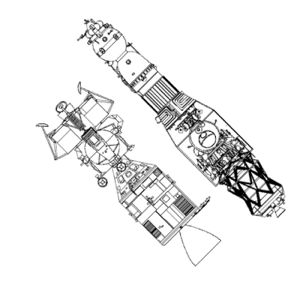

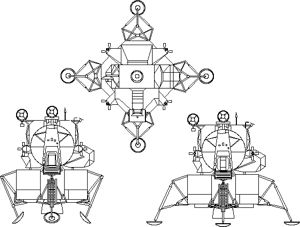

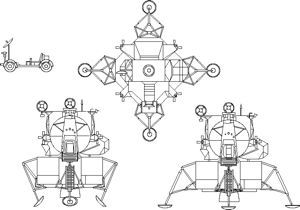

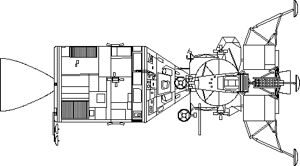

Apollo vs N1-L3 Apollo CSM / LM vs L3 Lunar Complex Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo Lunar Landing American manned lunar expedition. Begun in 1962; first landing on the moon 1969; sixth and final lunar landing 1972. The project that succeeded in putting a man on the moon. |

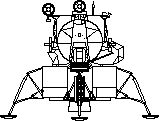

| Apollo LM American manned lunar lander. |

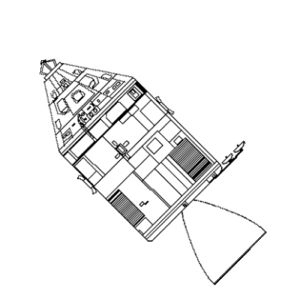

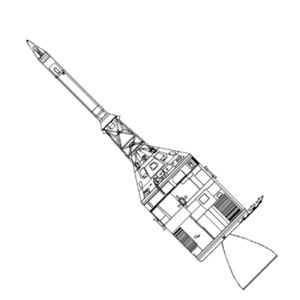

| Apollo CSM The Apollo Command Service Module was the spacecraft developed by NASA in the 1960's as a standard spacecraft for earth and lunar orbit missions. Manned spacecraft for earth orbit and lunar orbit satellite operated by NASA, USA. Launched 1967 - 1975. |

| Apollo CM American manned spacecraft module. 22 launches, 1964.05.28 (Saturn 6) to 1975.07.15 (Apollo (ASTP)). |

| Apollo SM American manned spacecraft module. 22 launches, 1964.05.28 (Saturn 6) to 1975.07.15 (Apollo (ASTP)). |

| Apollo LM DS American manned spacecraft module. 10 launches, 1968.01.22 (Apollo 5) to 1972.12.07 (Apollo 17). |

| Apollo LM AS American manned spacecraft module. 10 launches, 1968.01.22 (Apollo 5) to 1972.12.07 (Apollo 17). |

| Apollo A American manned space station. Study 1961. Apollo A was a lighter-weight July 1961 version of the Apollo spacecraft. |

| Apollo X American manned space station. Study 1963. |

| Apollo Martin 410 American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. The Model 410 was Martin's preferred design for the Apollo spacecraft. |

| Apollo Direct TLM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. Final letdown, translation hover and landing on the lunar surface from 1800 m above the surface was performed by the terminal landing module. Engine thrust could be throttled down to 1546 kgf. |

| Apollo Direct SM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. The Service Module housed the fuel cells, environmental control, and other major equipment items required for the mission. |

| Apollo Direct RM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. The retrograde module supplied the velocity increments required during the translunar portion of the mission up to a staging point approximately 1800 m above the lunar surface. |

| Apollo Direct CM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. Conventional spacecraft structures were employed, following the proven materials and concepts demonstrated in the Mercury and Gemini designs. |

| Apollo Direct 2-Man American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. A direct lunar lander design of 1961, capable of being launched to the moon in a single Saturn V launch through use of a 75% scale 2-man Apollo command module. |

| LM Langley Lighter American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. This early open-cab Langley design used cryogenic propellants. The cryogenic design was estimated to gross 3,284 kg - to be compared with the 15,000 kg / 2 man LM design that eventually was selected. |

| LM Langley Lightest American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. Extremely light-weight open-cab lunar module design considered in early Langley studies. |

| LM Langley Light American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. This early open-cab single-crew Langley lunar lander design used storable propellants, resulting in an all-up mass of 4,372 kg. |

| Apollo ULS American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1962. An Apollo unmanned logistic system to aid astronauts on a lunar landing mission was studied. |

| Apollo W-1 American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. Martin's W-1 design for the Apollo spacecraft was an alternative to the preferred L-2C configuration. The 2652 kg command module was a blunt cone lifting body re-entry vehicle, 3.45 m in diameter, 3.61 m long. |

| Apollo M-1 American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. Convair/Astronautics preferred M-1 Apollo design was a three-module lunar-orbiting spacecraft. |

| Apollo D-2 American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1962. The General Electric design for Apollo put all systems and space not necessary for re-entry and recovery into a separate jettisonable 'mission module', joined to the re-entry vehicle by a hatch. |

| Apollo R-3 American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. General Electric's Apollo horizontal-landing alternative to the ballistic D-2 capsule was the R-3 lifting body. This modified lenticular shape provided a lift-to-drag ratio of just 0. |

| Apollo L-2C American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. Martin's L-2C design was the basis for the Apollo spacecraft that ultimately emerged. The 2590 kg command module was a flat-bottomed cone, 3. 91 m in diameter, 2.67 m high, with a rounded apex. |

| Apollo Lenticular American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. The Convair/Astronautics alternate Lenticular Apollo was a flying saucer configuration with the highest hypersonic lift to drag ratio (4.4) of any proposed design. |

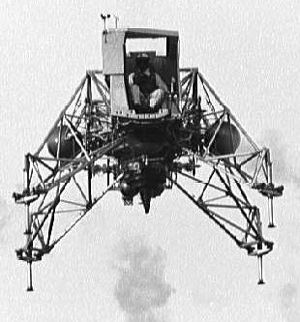

| Apollo LLRV American manned lunar lander test vehicle. Bell Aerosystems initially built two manned lunar landing research vehicles (LLRV) for NASA to assess the handling characteristics of Apollo LM-type vehicles on earth. |

| Apollo LLRF American Lunar Landing Research Facility. The huge structure (76.2 m high and 121.9 m long) was used to explore techniques and to forecast various problems of landing on the moon. |

| Apollo LES American test vehicle. Flight tests from a surface pad of the Apollo Launch Escape System using a boilerplate capsule. |

| Apollo LM Shelter American manned lunar habitat. Cancelled 1968. The LM Shelter was essentially an Apollo LM lunar module with ascent stage engine and fuel tanks removed and replaced with consumables and scientific equipment for 14 days extended lunar exploration. |

| Apollo LM Taxi American manned lunar lander. Cancelled 1968. The LM Taxi was essentially the basic Apollo LM modified for extended lunar surface stays. |

| Apollo CSM Boilerplate American manned spacecraft. Boilerplate structural Apollo CSM's were used for various systems and booster tests, especially proving of the LES (launch escape system). |

| Apollo CSM Block I American manned spacecraft. The Apollo Command Service Module was the spacecraft developed by NASA in the 1960's as a standard spacecraft for earth and lunar orbit missions. |

| FIRE American re-entry vehicle technology satellite. 2 launches, 1964.04.14 (FIRE 1) and 1965.05.22 (FIRE 2). Suborbital re-entry test program that used a subscale model of the Apollo Command Module to verify the configuration at high reentry speed. Reentry Technology satellite built by Republic Aviation Corporation for NASA. |

| Apollo LM Truck American lunar logistics spacecraft. Cancelled 1968. The LM Truck was an LM Descent stage adapted for unmanned delivery of payloads of up to 5,000 kg to the lunar surface in support of a lunar base using Apollo technology. |

| Apollo MSS American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1965. The Apollo Mapping and Survey System was a kit of photographic equipment that was at one time part of the basic Apollo Block II configuration. |

| Apollo LM Lab American manned space station. Study 1965. Use of the Apollo LM as an earth-orbiting laboratory was proposed for Apollo Applications Program missions. |

| Apollo SA-11 From September 1962 NASA planned to fly four early manned Apollo spacecraft on Saturn I boosters. Cancelled in October 1963 in order to fly all-up manned Apollo CSM on more powerful Saturn IB. |

| Apollo Experiments Pallet American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1965. The Apollo Experiments Pallet was a sophisticated instrument payload that would have been installed in the Apollo CSM for dedicated lunar or earth orbital resource assessment missions. |

| Apollo LM CSD American manned combat spacecraft. Study 1965. The Apollo Lunar Module was considered for military use in the Covert Space Denial role in 1964. |

| Apollo SA-12 From September 1962 NASA planned to fly four early manned Apollo spacecraft on Saturn I boosters. Cancelled in October 1963 in order to fly all-up manned Apollo CSM on more powerful Saturn IB. |

| Apollo LMSS American manned space station. Cancelled 1967. Under the Apollo Applications Program NASA began hardware and software procurement, development, and testing for a Lunar Mapping and Survey System. The system would be mounted in an Apollo CSM. |

| Apollo SA-13 From September 1962 NASA planned to fly four early manned Apollo spacecraft on Saturn I boosters. Cancelled in October 1963 in order to fly all-up manned Apollo CSM on more powerful Saturn IB. |

| Apollo SA-14 From September 1962 NASA planned to fly four early manned Apollo spacecraft on Saturn I boosters. Cancelled in October 1963 in order to fly all-up manned Apollo CSM on more powerful Saturn IB. |

| Apollo LASS S-IVB American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1966. The Douglas Company (DAC) proposed the "Lunar Application of a Spent S-IVB Stage (LASS)". The LASS concept required a landing gear on a S-IVB Stage. |

| Apollo SMLL American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1966. North American Aviation (NAA) proposed use of the SM as a lunar logistics vehicle (LLV) in 1966. The configuration, simply stated, put a landing gear on the SM. |

| Apollo CMLS American manned lunar habitat. Study 1966. |

| Apollo 204 The planned first manned flight of the Apollo CSM, the Apollo C category mission. The crew was killed in a fire while testing their capsule on the pad on 27 January 1967, still weeks away from launch. Set back Apollo program by 18 months. |

| Apollo 205 Planned second solo flight test of the Block I Apollo CSM on a Saturn IB. Cancelled after the Apollo 204 fire. |

| Apollo 207 Planned Apollo D mission. Two Saturn IB launches would put Apollo CSM and LM into orbit. CSM crew would dock with LM, test it in earth orbit. Cancelled after Apollo 204 fire. |

| Apollo LTA American technology satellite. 3 launches, 1967.11.09 (LTA-10R) to 1968.12.21 (LTA-B). Apollo Lunar module Test Articles were simple mass/structural models of the Lunar Module. |

| Apollo 503 Cancelled Apollo E mission - test of the Apollo lunar module in high earth orbit. Lunar module was not ready. Instead mission flown only with CSM into lunar orbit as Apollo 8. |

| Apollo RM American logistics spacecraft. Study 1967. In 1967 it was planned that Saturn IB-launched Orbital Workshops would be supplied by Apollo CSM spacecraft and Resupply Modules (RM) with up to three metric tons of supplies and instruments. |

| Apollo 7 First manned test of the Apollo spacecraft. Although the systems worked well, the crew became grumpy with head colds and talked back to the ground. As a result, NASA management determined that none of them would fly again. |

| Apollo 8 First manned flight to lunar orbit. Speed (10,807 m/s) and altitude (378,504 km) records. Mission resulted from audacious decision to send crew around moon to beat Soviets on only second manned Apollo CSM mission and third Saturn V launch. |

| Apollo 120 in Telescope American manned space station. Study 1968. Concept for use of a Saturn V-launched Apollo CSM with an enormous 10 m diameter space laboratory equipped with a 3 m diameter astronomical telescope. |

| Apollo LMAL American manned space station. Study 1968. |

| Apollo LPM American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1968. The unmanned portion of the Lunar Surface Rendezvous and Exploration Phase of Apollo envisioned in 1969 was the Lunar Payload Module (LPM). |

| Apollo LASS American manned lunar habitat. Cancelled 1968. In the LASS (LM Adapter Surface Station) lunar shelter concept, the LM ascent stage was replaced by an SLA 'mini-base' and the position of the Apollo Service Module (SM) was reversed. |

| Apollo ELS American manned lunar habitat. Cancelled 1968. The capabilities of a lunar shelter not derived from Apollo hardware were surveyed in the Early Lunar Shelter Study (ELS), completed in February 1967 by AiResearch. |

| Apollo 9 First manned test of the Lunar Module. First test of the Apollo space suits. First manned flight of a spacecraft incapable of returning to earth. If rendezvous of the Lunar Module with the Apollo CSM had failed, crew would have been stranded in orbit. |

| Apollo 10 Final dress rehearsal in lunar orbit for landing on moon. LM separated and descended to 10 km from surface of moon but did not land. Speed record (11,107 m/s). |

| Apollo 11 First manned lunar landing. The end of the moon race and public support for large space programs. The many changes made after the Apollo 204 fire paid off; all went according to plan, virtually no problems. |

| Apollo ALSEP American lunar lander. 7 launches, 1969.07.16 (EASEP) to 1972.12.07 (ALSEP). ALSEP (Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package) was the array of connected scientific instruments left behind on the lunar surface by each Apollo expedition. |

| Apollo LRM American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1969. Grumman proposed to use the LM as a lunar reconnaissance module. But NASA had already considered this and many other possibilities (Apollo MSS, Apollo LMSS); and there was no budget available for any of them. |

| Apollo 12 Second manned lunar landing. Precision landing near Surveyor 3 that landed in 1967. Lightning struck the booster twice during ascent. Decision was made to press on to moon, despite possibility landing pyrotechnics damaged. |

| Apollo MET American lunar hand cart. Flown 1971. NASA designed the MET lunar hand cart to help with problems such as the Apollo 12 astronauts had in carrying hand tools, sample boxes and bags, a stereo camera, and other equipment on the lunar surface. |

| Apollo 13 Fuel cell tank exploded en route to the moon, resulting in loss of all power and oxygen. Only through use of the still-attached LM as a lifeboat could the crew survive to return to earth. Altitude (401,056 km) record. |

| Apollo: Soviets Recovered an Apollo Capsule! The truth only emerged 32 years later - the Soviets recovered an Apollo space capsule in 1970… the original article. |

| Apollo Rescue CSM American manned rescue spacecraft. Study 1970. Influenced by the stranded Skylab crew portrayed in the book and movie 'Marooned', NASA provided a crew rescue capability for the first time in its history. |

| Apollo 14 Third manned lunar landing. Only Mercury astronaut to reach moon. Five attempts to dock the command module with the lunar module failed for no apparent reason - mission saved when sixth was successful. Hike to Cone Crater frustrating; rim not reached. |

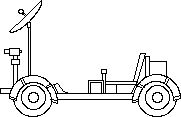

| Apollo LRV American manned lunar rover. The Apollo Lunar Roving Vehicle was one of those sweet pieces of hardware that NASA and its contractors seemed to be able to develop so effortlessly during the short maturity of the Apollo program. The Lunar Rover was the only piece of equipment from NASA's ambitious post-Apollo lunar exploration plans to actually fly in space, being used on Apollo missions 15, 16, and 17 in 1971-1972. The design was based on three years of studies for light, two-crew, open-cockpit 'Local Science Survey Modules'. Although Bendix built a prototype, Boeing ended up with the production contract. |

| Apollo 15 First use of lunar rover on moon. Beautiful images of crew prospecting at edge of Hadley Rill. One of the three main parachutes failed, causing a hard but survivable splashdown. |

| Apollo 16 Second Apollo mission with lunar rover. CSM main engine failure detected in lunar orbit. Landing almost aborted. |

| Apollo 17 Final Apollo lunar landing mission. First geologist to walk on the moon. |

| Apollo 18 Apollo 18 was originally planned in July 1969 to land in the moon's Schroter's Valley, a river-like channel-way. The original February 1972 landing date was extended when NASA cancelled the Apollo 20 mission in January 1970. Apollo 18 in turn cancelled on 2 September 1970 because of congressional cuts in FY 1971 NASA appropriations. |

| Apollo 19 Apollo 19 was originally planned to land in the Hyginus Rille region, which would allow study of lunar linear rilles and craters. Apollo 19 in turn cancelled on 2 September 1970 because of congressional cuts in FY 1971 NASA appropriations. |

| Apollo 20 Apollo 20 was originally planned in July 1969 to land in Crater Copernicus, a spectacular large crater impact area. Later Copernicus was assigned to Apollo 19, and the preferred landing site for Apollo 20 was the Marius Hills, or, if the operational constraints were relaxed, the bright crater Tycho. The planned December 1972 flight was cancelled on January 4, 1970, before any crew assignments were made. |

| Apollo ASTP Docking Module American manned space station module. Docking Module 2. The ASTP docking module was basically an airlock with docking facilities on each end to allow crew transfer between the Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft. |

| Apollo CM Escape Concept American manned rescue spacecraft. Study 1976. Escape capsule using Apollo command module studied by Rockwell for NASA for use with the shuttle in the 1970's-80's. Mass per crew: 750 kg. |

People: Schirra, Shepard, Cooper, Borman, Lovell, McDivitt, Gordon, Aldrin, Pogue, Irwin, Conrad, Eisele, Armstrong, Mitchell, Stafford, Young, Collins, Brand, Swigert, Worden, Kerwin, Bean, Cunningham, Scott, Engle, Roosa, Anders, Evans, Haise, Cernan, Chapman, Schmitt, Duke, Schweickart, Lousma, Mattingly, McCandless. Country: USA. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, Apollo CSM, Jupiter nose cone, Pegasus satellite, PFS. Flights: Apollo SA-11, Apollo SA-12, Apollo SA-13, Apollo SA-14, Apollo 204, Apollo 205, Apollo 207, Apollo 503, Apollo 7, Apollo 8, Apollo 9, Apollo 10, Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 13, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16, Apollo 17, Apollo 18, Apollo 19, Apollo 20. Launch Vehicles: Saturn I, Saturn IB, Uprated Saturn I, Saturn V. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral. Agency: NASA Huntsville, NASA Houston. Bibliography: 4889, 9246.

| Apollo with Vanes Credit: NASA |

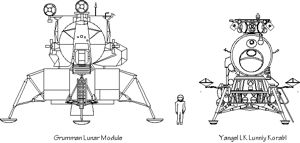

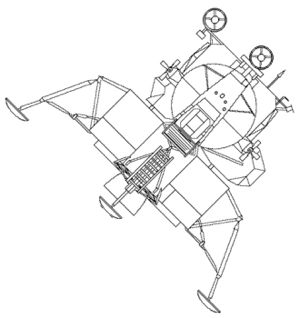

| LM vs LK US Lunar Module compared to Soviet LK lunar lander Credit: © Mark Wade |

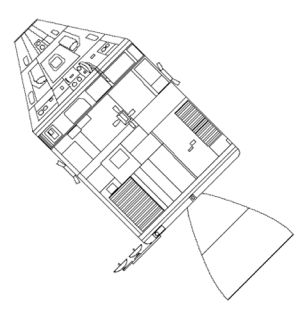

| Apollo CSM Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Lunar rover Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Lunar Module 3 view Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apolo LM Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM and LM Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM Interior Interior of the Apollo Command Service Module on display at Kennedy Space Centre, Florida. Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo Lunar Module Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM Apollo CSM with Launch Escape Tower Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Lunar Module Lunar Module front view Credit: © Mark Wade |

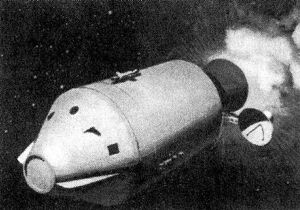

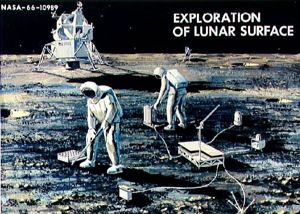

| Apollo Artist concept of Apollo Lunar Mission Touchdown on Lunar Surface Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Artist concept of Apollo Lunar Mission Exploration of Lunar Surface Credit: NASA |

| Apollo One-twentieth size engineering model of the Apollo Lunar Excursion Module Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp. artist's concept of Lunar Module 5 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Artist's concept of a Saturn launch Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Artist's concept of a Saturn launch Credit: NASA |

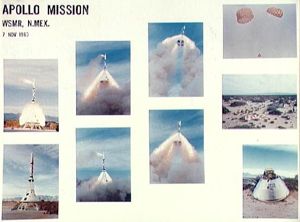

| Apollo Little Joe II lift-off from launch area #3 at White Sands Credit: NASA |

| Apollo View of the lift-off of Little Joe II Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Boilerplate 6 and firing sequence of Apollo-Little Joe Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Apollo Mission (BP-6) composite Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Launch of Saturn 7 at Launch Complex 37, Merritt Island launch area, Florid Credit: NASA |

| Apollo First night launch of a Saturn I launch vehicle Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Night time view of Apollo Spacecraft 009 atop Saturn 1B launch vehicle Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Apollo/Saturn 201 launched from Kennedy Space Center Credit: NASA |

| Apollo KSC Launch Complex 34 during Apollo/Saturn Mission 202 pre-launch alert Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Apollo/Saturn Mission 202 launch Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Lift-off of Saturn Mission 203 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Artist's concept of prototype of Apollo Space suit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Space suit A-3H-024 with Lunar Excursion Module astronaut restraint harness Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Test subject wears Apollo overgarment designed for use on lunar surface Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Astronaut John Bull wears newly designed Apollo pressure suit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo Portrait of Scientist-Astronauts whose selection was announced June 29, 196 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo LLTV Lunar Landing Training vehicle piloted by Neil Armstrong during training Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Early morning view of Apollo 4 unmanned spacecraft on launch pad Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Apollo 4 unmanned mission launched from Pad A, Launch Complex 39 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Launching of the Apollo 4 unmanned space mission Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Apollo 4 unmanned mission launched from Pad A, Launch Complex 39 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Brazil, Atlantic Ocean, Africa, Sahara & Antarctica seen from Apollo 4 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Brazil, Atlantic Ocean, Africa & Antarctica seen from Apollo 4 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Atlantic Ocean, Antarctica as seen from the Apollo 4 unmanned spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 4 Apollo spacecraft 017 is hoisted aboard U.S.S. Bennington Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 5 Mating of Lunar Module-1 with Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter-7 Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 5 Apollo 5 lift-off Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 5 Apollo 5 lift-off Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 5 Apollo 5 lift-off Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 6 F-1 engines of Apollo/Saturn V first stage leave trail of flame after lift-off Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 6 Recovery of Apollo 6 unmanned spacecraft Credit: NASA |

1953 March - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Research on 1 million lb thrust engine begun. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Research on 1-million-pound thrust plus engine begun at Rocketdyne, the feasibility of which was established in March 1955..

1955 March - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Feasibility of million-pound-thrust liquid-fueled rocket engine established - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The feasibility of a million-pound-thrust liquid-fueled rocket engine established by the Rocketdyne Division of North American Aviation, Inc..

1956 January 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First test of 400,000+ lb thrust engine. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. First U.S.-built complete liquid-rocket engine having a thrust in excess of 400,000 pounds was fired for the first time at Santa Susana, Calif..

1956 November 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Million pound thrust test stand activiated. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocket test stand capable of testing engines to 1 million pounds thrust activated at Edwards AFB, which became operational in March 1957..

1957 April - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Studies of a large clustered-engine booster - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency, Redstone Arsenal, Ala., began studies of a large clustered-engine booster to generate 1.5 million pounds of thrust, as one of a related group of space vehicles. During 1957-1958, approximately 50,000 man-hours were expended in this effort.

1957 December 30 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I first proposed. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Von Braun produces 'Proposal for a National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Plan'. First mention of 1,500,000 lbf booster (Saturn I).

1958 February 10 - .

- Expanded NACA program of space flight research proposed - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

A greatly expanded NACA program of space flight research was proposed in a paper, "A Program for Expansion of NACA Research in Space Flight Technology," written principally by senior engineers of the Lewis Aeronautical Laboratory under the leadership of Abe Silverstein. The goal of the program would be "to provide basic research in support of the development of manned satellites and the travel of man to the moon and nearby planets." The cost of the program was estimated at $241 million per year above the current NACA budget.

1958 June 23 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Preliminary design begun on F-1 - 1.5 million pounds thrust rocket engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The U.S. Air Force contracted with NAA, Rocketdyne Division, for preliminary design of a single-chamber, kerosene and liquid-oxygen rocket engine capable of 1 to 1.5 million pounds of thrust. During the last week in July, Rocketdyne was awarded the contract to develop this engine, designated the F-1.

1958 July 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I initial contract. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. ARPA gives Von Braun team contract to develop Saturn I (called 'cluster's last stand' due to design concept)..

1958 August 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rocketdyne gets F-1 engine contract. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocketdyne Division of North American announced an Air Force contract for a 1-million-pound thrust engine..

1958 August 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I project initiated by ARPA. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA provided the Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) with authority and initial funding to develop the Juno V (later named Saturn launch vehicle. ARPA Order 14 described the project: "Initiate a development program to provide a large space vehicle booster of approximately 1.5 million pounds of thrust based on a cluster of available rocket engines. The immediate goal of this program is to demonstrate a full-scale captive dynamic firing by the end of calendar year 1959." Within AOMC, the Juno V project was assigned to the Army Ballistic Missile Agency at Redstone Arsenal Huntsville, Ala.

1958 September 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Redstone Arsenal begins Saturn I design studies. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Saturn design studies authorized to proceed at Redstone Arsenal for development of 1.5-million-pound-thrust cluster first stage..

1958 September 11 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Letter contract for the development of the Saturn H-1 rocket engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. A letter contract was signed by NASA with NAA's Rocketdyne Division for the development of the H-1 rocket engine, designed for use in a clustered-engine booster..

1958 October 11 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Contract for development of the H-1 engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Pioneer I, intended as a lunar probe, was launched by a Thor-Able rocket from the Atlantic Missile Range, with the Air Force acting as executive agent to NASA. The 39-pound instrumented payload did not reach escape velocity..

1958 October 25 - .

- Stever Committee report on the civilian space program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

The Stever Committee, which had been set up on January 12, submitted its report on the civilian space program to NASA. Among the recommendations:

- A vigorous, coordinated attack should be made upon the problems of maintaining the performance capabilities of man in the space environment as a prerequisite to sophisticated space exploration.

- Sustained support should be given to a comprehensive instrumentation development program, establishment of versatile dynamic flight simulators, and provision of a coordinated series of vehicles for testing components and subsystems.

- Serious study should be made of an equatorial launch capability.

- Lifting reentry vehicles should be developed.

- Both the clustered- and single-engine boosters of million-pound thrust should be developed.

- Research on high-energy propellant systems for launch vehicle upper stages should receive full support.

- The performance capabilities of various combinations of existing boosters and upper stages should be evaluated, and intensive development concentrated on those promising greatest usefulness in different categories of payload.

1958 November 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- F-1 engine gets highest priority. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA requested DX priority for 1.5-million-pound-thrust F-1 engine project and Project Mercury..

1958 November 1 - .

- Contract for lunar mapping photography - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

A contract was signed by the University of Manchester, Manchester, England, and the Air Force (AF 61(052)-168) for $21,509. Z. Kopal, principal investigator, was to provide topographical information on the lunar surface for production of accurate lunar maps. Additional Details: here....

1958 November 5 - .

- Space Task Group (STG) organized to implement the manned satellite project - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth,

Glennan.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

The Space Task Group (STG) was officially organized at Langley Field, Va., to implement the manned satellite project (later Project Mercury), NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan had approved the formation of the Group, which had been working together for some months, on October 7. Its members were designated on November 3 by Robert R. Gilruth, Project Manager, and authorization was given by Floyd L. Thompson, Acting Director of Langley Research Center. STG would report directly to NASA Headquarters.

1958 December 3 - .

- Army / NASA cooperative agreements - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Glennan,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker and NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan signed cooperative agreements concerning NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Army Ordnance Missile Command AOMC, and Department of the Army relationships. The agreement covering NASA utilization of the von Braun team made "the AOMC and its subordinate organizations immediately, directly, and continuously responsive to NASA requirements."

1958 December 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- ABMA Briefing to NASA - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. Von Braun briefs NASA on plans for booster development at Huntsville with objective of manned lunar landing. Initally proposed using 15 Juno V (Saturn I) boosters to assemble 200,000 kg payload in earth orbit for direct landing on moon..

1958 December 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn H-1 engine first full-power firing - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The H-1 engine successfully completed its first full-power firing at NAA's Rocketdyne facility in Canoga Park, Calif..

1958 December 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rocketdyne gets contract to develop F-1 engine. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA awarded contract to Rocketdyne of North American to build single-chamber 1.5-million-pound-thrust rocket engine..

1958 December 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Military and NASA consider future launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Representatives of Advanced Research Projects Agency, the military services, and NASA met to consider the development of future launch vehicle systems. Agreement was reached on the principle of developing a small number of versatile launch vehicle systems of different thrust capabilities, the reliability of which could be expected to be improved through use by both the military services and NASA.

1959 January 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- 1 million pound engine demonstrated. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocketdyne demonstrated 1-million-pound-thrust liquid-propellant rocket combustion chamber at full power..

1959 January 2 - .

- Von Braun predicted manned circumlunar flight within ten years - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Glennan,

Silverstein,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

In a staff report of the House Select Committee on Astronautics and Space Exploration, Wernher von Braun of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency predicted manned circumlunar flight within the next eight to ten years and a manned lunar landing and return mission a few years thereafter. Administrator T. Keith Glennan, Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden, Abe Silverstein, John P. Hagen, and Homer E. Newell, all of NASA, also foresaw manned circumlunar flight within the decade as well as instrumented probes soft-landed on the moon. Roy K. Knutson, Chairman of the Corporate Space Committee, NAA, projected a manned lunar landing expedition for the early 1970's with extensive unmanned instrumented soft lunar landings during the last half of the 1960's.

1959 January 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- NASA Large Booster Review Committee - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC), the Air Force, and missile contractors presented to the ARPA-NASA Large Booster Review Committee their views on the quickest and surest way for the United States to attain large booster capability. The Committee decided that the Juno V approach advocated by AOMC was best and NASA started plans to utilize the Juno V booster.

1959 January 19 - .

- Contract with Rocketdyne for development of the F-1 engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA signed a definitive contract with Rocketdyne Division, NAA, for $102 million covering the design and development of a single-chamber, liquid-propellant rocket engine in the 1- to l.5-million-pound-thrust class (the F-1, to be used in the Nova superbooster concept). NASA had announced the selection of Rocketdyne on December 12.

1959 January 27 - .

- NASA National Space Vehicle Program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

After consultation and discussion with DOD, NASA formulated a national space vehicle program. The central idea of the program was that a single launch vehicle should be developed for use in each series of future space missions. The launch vehicle would thus achieve a high degree of reliability, while the guidance and payload could be varied according to purpose of the mission. Four general-purpose launch vehicles were described: Vega, Centaur, Saturn, and Nova. The Nova booster stage would be powered by a cluster of four F-1 engines, the second stage by a single F-1, and the third stage would be the size of an intercontinental ballistic missile but would use liquid hydrogen as a fuel. This launch vehicle would be the first in a series that could transport a man to the lunar surface and return him safely to earth in a direct ascent mission. Four additional stages would be required in such a mission.

1959 February 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Booster name changed from Juno V to Saturn - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Johnson, Roy, von Braun. Program: Apollo. The Army proposed that the name of the large clustered-engine booster be changed from Juno V to Saturn, since Saturn was the next planet after Jupiter. Roy W. Johnson, Director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency, approved the name on February 3..

1959 February 4 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Early agreement required on Saturn upper stages - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Roy,

Medaris,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Maj. Gen. John B. Medaris of the Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) and Roy W. Johnson of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) discussed the urgency of early agreement between ARPA and NASA on the configuration of the Saturn upper stages. Several discussions between ARPA and NASA had been held on this subject. Johnson expected to reach agreement with NASA the following week. He agreed that AOMC would participate in the overall upper stage planning to ensure compatibility of the booster and upper stages.

1959 February 5 - .

- Working Group on Lunar Exploration established by NASA - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

A Working Group on Lunar Exploration was established by NASA at a meeting at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Members of NASA, JPL, Army Ballistic Missile Agency, California Institute of Technology, and the University of California participated in the meeting. The Working Group was assigned the responsibility of preparing a lunar exploration program, which was outlined: circumlunar vehicles, unmanned and manned; hard lunar impact; close lunar satellites; soft lunar landings (instrumented). Preliminary studies showed that the Saturn booster with an intercontinental ballistic missile as a second stage and a Centaur as a third stage, would be capable of launching manned lunar circumnavigation spacecraft and instrumented packages of about one ton to a soft landing on the moon.

1959 February 15 - .

- NASA Booster Development Plan for 60's - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. NASA issues plan for development in next decade of Vega (later cancelled as too similar to Agena), Centaur, Saturn, and Nova launch vehicles. Juno V renamed Saturn I..

1959 February 17 - .

- Exploration of the moon a NASA responsibility - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Roy.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Roy W. Johnson, Director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), testified before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics that DOD and ARPA had no lunar landing program. Herbert F. York, DOD Director of Defense Research and Engineering, testified that exploration of the moon was a NASA responsibility.

1959 February 20 - .

- Long-range objectives of the NASA space program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

In testimony before the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden and DeMarquis D. Wyatt described the long-range objectives of the NASA space program: an orbiting space station with several men, operating for several days; a permanent manned orbiting laboratory; unmanned hard-landing and soft-landing lunar probes; manned circumlunar flight; manned lunar landing and return; and, ultimately, interplanetary flight.

1959 March - .

- Heatshield test of Mercury at lunar reentry speeds - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

H. Kurt Strass and Leo T. Chauvin of STG proposed a heatshield test of a fullscale Mercury spacecraft at lunar reentry speeds. This test, in which the capsule would penetrate the earth's radiation belt, was called Project Boomerang. An advanced version of the Titan missile was to be the launch vehicle. The project was postponed and ultimately dropped because of cost.

1959 March 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Thrust chamber of the Saturn F-1 engine successfully static-fired - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The thrust chamber of the F-1 engine was successfully static-fired at the Santa Susana Air Force-Rocketdyne Propulsion Laboratory in California. More than one million pounds of thrust were produced, the greatest amount attained to that time in the United States.

1959 March 13 - .

- Saturn System Study - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) submitted the "Saturn System Study" which had been requested by the Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA on December 18, 1958. From the 1375 possible configurations screened, and the 14 most promising given detailed study, the Atlas and Titan families were selected as the most attractive for upper staging. Either the 120-inch or the 160inch diameter was acceptable. The study included the statement: "An immediate decision by ARPA as to choice of upper stages on the first generation vehicle is mandatory if flight hardware is to be available to meet the proposed Saturn schedule." Additional Details: here....

1959 April 1-8 - .

- Goett Committee to study advanced manned space flight missions - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett.

Program: Apollo.

John W. Crowley, Jr., NASA Director of Aeronautical and Space Research, notified the Ames, Lewis, and Langley Research Centers, the High Speed Flight Station (later Flight Research Center), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Office of Space Flight Development that a Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight would be formed. Harry J. Goett of Ames was to be Chairman of the Committee, which would assist NASA Headquarters in carrying out its responsibilities in long-range planning and basic research on manned space flight.

1959 April 2-5 - .

- Advanced manned space program to follow Project Mercury - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

The advanced manned space program to follow Project Mercury was discussed at a NASA Staff Conference held in Williamsburg, Va. Three reasons for such a program were suggested:

- Preliminary step to development of spacecraft for manned interplanetary exploration.

- Extended duration work in the space environment.

- Support of the military space mission.

1959 April 7 - .

- Research into rendezvous techniques - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan requested $3 million for research into rendezvous techniques as part of the NASA budget for Fiscal Year 1960. In subsequent hearings, DeMarquis D. Wyatt, Assistant to the NASA Director of Space Flight Development, explained that these funds would be used to resolve certain key problems in making space rendezvous practical. Among these were the establishment of referencing methods for fixing the relative positions of two vehicles in space; the development of accurate, lightweight target-acquisition equipment to enable the supply craft to locate the space station; the development of very accurate guidance and control systems to permit precisely determined flight paths; and the development of sources of controlled power.

1959 April 8 - .

- Network of stations for deep-space probes - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Testifying before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Francis B. Smith, Chief of Tracking Programs for NASA, described the network of stations necessary for tracking a deep-space probe on a 24-hour basis. The stations should be located about 120 degrees apart in longitude. In addition to the Goldstone, Calif., site, two other locations had been selected: South Africa and Woomera, Australia.

1959 April 9-28 - .

- Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight members nominated - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Members of the new Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight were nominated by the Ames, Lewis, and Langley Research Centers, the High Speed Flight Station (HSFS) (later Flight Research Center), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the Office of Space Flight Development OSFD), and the Office of Aeronautical and Space Research (OASR). They were: Alfred J. Eggers, Jr. (Ames); Bruce T. Lundin (Lewis); Laurence K. Loftin, Jr. (Langley); De E. Beeler (HSFS); Harris M. Schurmeier (JPL); Maxime A. Faget (STG) ; George M. Low of NASA Headquarters OSFD) ; and Milton B. Ames, Jr. (part-time) (OASR).

1959 April 15 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn A-1.

- Use of Titan for Saturn upper stages - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

In response to a request by the DOD-NASA) Saturn Ad Hoc Committee, the Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) sent a supplement to the "Saturn System Study" to the Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA describing the use of Titan for Saturn upper stages. Additional Details: here....

1959 May 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Unmanned Lunar Soft Landing Vehicle - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Surveyor. The Army Ordnance Missile Command submitted to NASA a report entitled "Preliminary Study of an Unmanned Lunar Soft Landing Vehicle," recommending the use of the Saturn booster..

1959 May 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First H-1 engine for the Saturn delivered - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The first Rocketdyne H-1 engine for the Saturn arrived at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA ). The H-1 engine was installed in the ABMA test stand on May 7, first test-fired on May 21, and fired for 80 seconds on May 29. The first long-duration firing - 151.03 seconds - was on June 2.

1959 May 6 - .

- Jastrow Committee on lunar exploration created. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA created a committee to study problems of long-range lunar exploration to be headed by Dr. Robert Jastrow..

1959 May 9 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas Vega.

- High-resolution photographs of the moon using Vega rocket - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Rosen, Milton.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Lunar Orbiter.

Milton W. Rosen of NASA Headquarters proposed a plan for obtaining high-resolution photographs of the moon. A three-stage Vega would place the payload within a 500-mile diameter circle on the lunar surface. A stabilized retrorocket fired at 500 miles above the moon would slow the instrument package sufficiently to permit 20 photographs to be transmitted at a rate of one picture per minute. Additional Details: here....

1959 May 25-26 - .

- Tentative manned space flight priorities - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

Tentative manned space flight priorities were established by the Research Steering Committee: Project Mercury, ballistic probes, environmental satellite, maneuverable manned satellite, manned space flight laboratory, lunar reconnaissance satellite, lunar landing, Mars Venus reconnaissance, and Mars-Venus landing. The Committee agreed that each NASA Center should study a manned lunar landing and return mission, the study to include the type of propulsion, vehicle configuration, structure, anti guidance requirements. Such a mission was an end objective; it did not have to be supported on the basis that it would lead to a more useful end. It would also focus attention at the Centers on the problems of true space flight.

1959 May 25-26 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- National booster program, Dyna-Soar, and Mercury discussed - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

The national booster program, Dyna-Soar, and Project Mercury were discussed by the Research Steering Committee. Members also presented reviews of Center programs related to manned space flight. Maxime A. Faget of STG endorsed lunar exploration as the present goal of the Committee although recognizing the end objective as manned interplanetary travel. George M. Low of NASA Headquarters recommended that the Committee:

- Adopt the lunar landing mission as its long-range objective.

- Investigate vehicle staging so that Saturn could be used for manned lunar landings without complete reliance on Nova.

- Make a study of whether parachute or airport landing techniques should be emphasized.

- Consider nuclear rocket propulsion possibilities for space flight.

- Attach importance to research on auxiliary power plants such as hydrogen-oxygen systems.

1959 May 25-26 - .

- First meeting of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Goett,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

The first meeting of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight was held at NASA Headquarters. Members of the Committee attending were: Harry J. Goett, Chairman; Milton B. Ames, Jr. (part-time); De E. Beeler; Alfred J. Eggers, Jr.; Maxime A. Faget; Laurence K. Loftin, Jr.; George M. Low; Bruce T. Lundin; and Harris M. Schurmeier. Observers were John H. Disher, Robert M. Crane, Warren J. North, Milton W. Rosen (part-time), and H. Kurt Strass.

The purpose of the Committee was to take a long-term look at man-in-space problems, leading eventually to recommendations on future missions and on broad aspects of Center research programs to ensure that the Centers were providing proper information. Committee investigations would range beyond Mercury and Dyna-Soar but would not be overly concerned with specific vehicular configurations. The Committee would report directly to the Office of Aeronautical and Space Research.

1959 May 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First H-1 engine for Saturn I fired. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. ABMA static fired a single H-1 Saturn engine at Redstone Arsenal, Ala..

1959 May 27 - .

- STG staff discusses the possibility of an advanced manned spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Faget,

Gilruth,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Director Robert R. Gilruth met with members of his STG staff (Paul E. Purser, Charles J. Donlan, James A. Chamberlin, Raymond L. Zavasky, W. Kemble Johnson, Charles W. Mathews, Maxime A. Faget, and Charles H. Zimmeman) and George M. Low from NASA Headquarters to discuss the possibility of an advanced manned spacecraft.

1959 June - .

- Recoverable Interplanetary Space Probe study - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: RISP. A report entitled "Recoverable Interplanetary Space Probe" was issued at the direction of C. Stark Draper, Director of the Instrumentation Laboratory, MIT. Several organizations had participated in this study, which began in 1957..

1959 June 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Construction begins of the first Saturn launch complex - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Construction of the first Saturn launch area, Complex 34, began at Cape Canaveral, FIa..

1959 June 4 - .

- Post-Mercury program using maneuverable Mercury spacecraft - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Gilruth. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Mercury. At an STG staff meeting, Director Robert R. Gilruth suggested that study should be made of a post-Mercury program in which maneuverable Mercury spacecraft would make land landings in limited areas..

1959 June 5 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

1959 June 18 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- NASA funded study of a lunar exploration program based on Saturn - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA authorized $150,000 for Army Ordnance Missile Command studies of a lunar exploration program based on Saturn-boosted systems. To be included were circumlunar vehicles, unmanned and manned; close lunar orbiters; hard lunar impacts; and soft lunar landings with stationary or roving payloads.

1959 Summer - .

- STG worked on advanced design concepts of earth orbital and lunar missions - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

Members of STG - including H. Kurt Strass, Robert L. O'Neal, Lawrence W. Enderson, Jr., and David C. Grana - and Thomas E. Dolan of Chance Vought Corporation worked on advanced design concepts of earth orbital and lunar missions. The goal was a manned lunar landing within ten years, rather than an advanced Mercury program.

1959 June 25-26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Study and research areas for manned flight to and from the moon - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Mercury. Members of the Research Steering Committee determined the study and research areas which would require emphasis for manned flight to and from the moon and for intermediate flight steps:. Additional Details: here....

1959 June 25-26 - .

- Research Steering Committee briefed on technical studies - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

Alfred J. Eggers, Jr., of the Ames Research Center told the members of the Research Steering Committee of studies on radiation belts, graze and orbit maneuvers on reentry, heat transfer, structural concepts and requirements, lift over drag considerations, and guidance systems which affected various aspects of the manned lunar mission. Eggers said that Ames had concentrated on a landing maneuver involving a reentry approach over one of the poles to lessen radiation exposure, a graze through the outer edge of the atmosphere to begin an earth orbit, and finally reentry and landing. Additional Details: here....

1959 June 25-26 - .

- Steps toward a manned lunar landing - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

At the second meeting of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight, held at the Ames Research Center, members presented reports on intermediate steps toward a manned lunar landing and return.

Bruce T. Lundin of the Lewis Research Center reported to members on propulsion requirements for various modes of manned lunar landing missions, assuming a 10,000-pound spacecraft to be returned to earth. Lewis mission studies had shown that a launch into lunar orbit would require less energy than a direct approach and would be more desirable for guidance, landing reliability, etc. From a 500,000 foot orbit around the moon, the spacecraft would descend in free fall, applying a constant-thrust decelerating impulse at the last moment before landing. Research would be needed to develop the variable-thrust rocket engine to be used in the descent. With the use of liquid hydrogen, the launch weight of the lunar rocket and spacecraft would be 10 to 11 million pounds. Additional Details: here....

1959 June 25-26 - .

- Projected manned space station - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

A report on a projected manned space station was made to the Research Steering Committee by Laurence K. Loftin, Jr., of the Langley Research Center. In discussion, Chairman Harry J. Goett expressed his opinion that consideration of a space laboratory ought to be an integral and coordinated part of the planning for the lunar landing mission. George M. Low of NASA Headquarters warned that care should be exercised to assure that each step taken toward the goal of a lunar landing was significant, since the number of steps that could be funded was extremely limited.

1959 August 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Static firing of the first Saturn planned for early 1960 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) directed the Army Ordnance Missile Command to proceed with the static firing of the first Saturn vehicle, the test booster SA-T, in early calendar year 1960 in accordance with the $70 million program and not to accelerate for a January 1960 firing. ARPA asked to be informed of the scheduled firing date.

1959 August-September - .

- Meetings of the STG New Projects Panel to discuss an advanced manned space flight program - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. Meetings of the STG New Projects Panel to discuss an advanced manned space flight program. .

1959 August 12 - .

- NASA's future manned space program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Parachute,

CSM Source Selection.

The STG New Projects Panel (proposed by H. Kurt Strass in June) held its first meeting to discuss NASA's future manned space program. Present were Strass, Chairman, Alan B. Kehlet, William S. Augerson, Jack Funk, and other STG members. Strass summarized the philosophy behind NASA's proposed objective of a manned lunar landing : maximum utilization of existing technology in a series of carefully chosen projects, each of which would provide a firm basis for the next step and be a significant advance in its own right. Additional Details: here....

1959 August 18 - .

- First major new NASA project to be a second-generation reentry capsule - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

At its second meeting, STG's New Projects Panel decided that the first major project to be investigated would be the second-generation reentry capsule. The Panel was presented a chart outlining the proposed sequence of events for manned lunar mission system analysis. The target date for a manned lunar landing was 1970.

1959 August 31 - .

- Lunar flights to originate from space platforms in earth orbit - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

A House Committee Staff Report stated that lunar flights would originate from space platforms in earth orbit according to current planning. The final decision on the method to be used, "which must be made soon," would take into consideration the difficulty of space rendezvous between a space platform and space vehicles as compared with the difficulty of developing single vehicles large enough to proceed directly from the earth to the moon.

1959 September 1 - .

- Mercury spacecraft modified to withstand lunar reentry conditions - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

McDonnell Aircraft Corporation reported to NASA the results of several company-funded studies of follow-on experiments using Mercury spacecraft with heatshields modified to withstand lunar reentry conditions. In one experiment, a Centaur booster would accelerate a Mercury spacecraft plus a third stage into an eccentric earth orbit with an apogee of about 1,200 miles, so that the capsule would reenter at an angle similar to that required for reentry from lunar orbit. The third stage would then fire, boosting the spacecraft to a speed of 36,000 feet per second as it reentered the atmosphere.

1959 September - .

- MIT study of the guidance and control design for a variety of space missions - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Guidance, CSM Source Selection. A study of the guidance and control design for a variety of space missions began at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory under a NASA contract..

1959 September 16-18 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan IIIC.

- Plans for advanced launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Glennan.

Program: Apollo.

The ARPA-NASA Booster Evaluation Committee appointed by Herbert F. York, DOD Director of Defense Research and Engineering, April 15, 1959, convened to review plans for advanced launch vehicles. A comparison of the Saturn (C-1) and the Titan-C boosters showed that the Saturn, with its substantially greater payload capacity, would be ready at least one year sooner than the Titan-C. In addition, the cost estimates on the Titan-C proved to be unrealistic. On the basis of the Advanced Research Projects Agency presentation, York agreed to continue the Saturn program but, following the meeting, began negotiations with NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan to transfer the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (and, therefore, Saturn ) to NASA.

1959 September 28 - .

- Lenticular-shaped vehicle proposed for the lunar mission - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

At the third meeting of STG's New Projects Panel, Alan B. Kehlet presented suggestions for the multimanned reentry capsule. A lenticular-shaped vehicle was proposed, to ferry three occupants safely to earth from a lunar mission at a velocity of about 36,000 feet per second.

1959 October 21 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Transfer to NASA of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Development Operations Division - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Eisenhower,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

After a meeting with officials concerned with the missile and space program, President Dwight D. Eisenhower announced that he intended to transfer to NASA control the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Development Operations Division personnel and facilities. The transfer, subject to congressional approval, would include the Saturn development program.

1959 November 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Transfer of Saturn I project to NASA announced. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Eisenhower, von Braun. Program: Apollo. President Eisenhower announced his intention of transferring the Saturn project to NASA, which became effective on March 15, 1960..

1959 November 2 - .

- Planning of advanced spacecraft systems begun - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Faget,

Gilruth,

Johnson, Caldwell.

Program: Apollo.

At an STG meeting, it was decided to begin planning of advanced spacecraft systems. Three primary assignments were made:

- The preliminary design of a multi-man (probably three-man) capsule for a circumlunar mission, with particular attention to the use of the capsule as a temporary space laboratory, lunar landing cabin, and deep-space probe;

- Mission analysis studies to establish exit and reentry corridors, weights, and propulsion requirements;

- Test program planning to decide on the number and purpose of launches.

1959 November 19 - .

- Importance of weight of end vehicle in the lunar landing mission - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

In a memorandum to the members of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight, Chairman Harry J. Goett discussed the increased importance of the weight of the "end vehicle" in the lunar landing mission. This was to be an item on the agenda of the third meeting of the Committee, to be held in early December. Abe Silverstein, Director of the NASA Office of Space Flight Development, had recently mentioned to Goett that a decision would be made within the next few weeks on the configuration of successive generations of Saturn, primarily the upper stages, Silverstein and Goett had discussed the Committee's views on a lunar spacecraft. Goett expressed the hope in the memorandum that members of the Committee would have some specific ideas at their forthcoming meeting about the probable weight of the spacecraft.

In addition, Goett informed the Committee that the Vega had been eliminated as a possible booster for use in one of the intermediate steps leading to the lunar mission. The primary possibility for the earth satellite mission was now the first-generation Saturn and for the lunar flight the second-generation Saturn.

1959 November 27 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Study group to recommend upper-stage configurations - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

While awaiting the formal transfer of the Saturn program, NASA formed a study group to recommend upper-stage configurations. Membership was to include the DOD Director of Defense Research and Engineering and personnel from NASA, Advanced Research Projects Agency, Army Ballistic Missile Agency, and the Air Force. This group was later known both as the Saturn Vehicle Team and the Silverstein Committee (for Abe Silverstein, Chairman).

1959 December 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Plan for transferring the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and Saturn to NASA - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Eisenhower,

Glennan,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The initial plan for transferring the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and Saturn to NASA was drafted. It was submitted to President Dwight D. Eisenhower on December 1 1 and was signed by Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker and Secretary of the Air Force James H. Douglas on December 16 and by NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan on December 17.

1959 December 7 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Engineering and cost study for a new Saturn configuration - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA and NASA requested the Army Ordnance Missile Command AOMC to prepare an engineering and cost study for a new Saturn configuration with a second stage of four 20,000-pound-thrust liquid-hydrogen and liquid-oxygen engines (later called the S-IV stage) and a modified Centaur third stage using two of these engines later designated the S-V stage). Additional Details: here....

1959 December 8-9 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Army Ballistic Missile Agency mission possibilities - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

H. H. Koelle told members of the Research Steering Committee of mission possibilities being considered at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. These included an engineering satellite, an orbital return capsule, a space crew training vehicle, a manned orbital laboratory, a manned circumlunar vehicle, and a manned lunar landing and return vehicle. He described the current Saturn configurations, including the "C" launch vehicle to be operational in 1967. The Saturn C (larger than the C-1) would be able to boost 85,000 pounds into earth orbit and 25,000 pounds into an escape trajectory.

1959 December 8-9 - .

- Steps to manned lunar flight and capsule-laboratory spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

At the third meeting of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight held at Langley Research Center, H. Kurt Strass reported on STG's thinking on steps leading to manned lunar flight and on a particular capsule-laboratory spacecraft. The project steps beyond Mercury were: radiation experiments, minimum space and reentry vehicle (manned), temporary space laboratory (manned), lunar data acquisition (unmanned), lunar circumnavigation or lunar orbiter (unmanned), lunar base supply (unmanned), and manned lunar landing. STG felt that the lunar mission should have a three-man crew. A configuration was described in which a cylindrical laboratory was attached to the reentry capsule. This laboratory would provide working space for the astronauts until it was jettisoned before reentry. Preliminary estimates put the capsule weight at about 6,600 pounds and the capsule plus laboratory at about 10,000 pounds.

1959 December 8-9 - .

- Configurations for manned lunar landing by direct ascent - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Several possible configurations for a manned lunar landing by direct ascent being studied at the Lewis Research Center were described to the Research Steering Committee by Seymour C. Himmel. A six-stage launch vehicle would be required, the first three stages to boost the spacecraft to orbital speed, the fourth to attain escape speed, the fifth for lunar landing, and the sixth for lunar escape with a 10,000-pound return vehicle. One representative configuration had an overall height of 320 feet. H. H. Koelle of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency argued that orbital assembly or refueling in orbit (earth orbit rendezvous) was more flexible, more straightforward, and easier than the direct ascent approach. Bruce T. Lundin of the Lewis Research Center felt that refueling in orbit presented formidable problems since handling liquid hydrogen on the ground was still not satisfactory. Lewis was working on handling cryogenic fuels in space.

1959 December 9 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Goett Committee - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. Committee formed to recommend post-Mercury space program. After four meetings, and studying earth-orbit assembly using Saturn II or direct ascent using Nova, tended to back development of Nova..

1959 December 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn upper stage study. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. NASA team completed study design of upper stages of Saturn launch vehicle..

1959 December 29 - .

- Space Exploration Program Council proposed - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

In a memorandum to Don R. Ostrander, Director of Office of Launch Vehicle Programs, and Abe Silverstein, Director of Office of Space Flight Programs, NASA Associate Administrator Richard E. Horner described the proposed Space Exploration Program Council, which would be concerned primarily with program development and implementation. The Council would be made up of the Directors of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Goddard Space Flight Center, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, the Office of Space Flight Programs, and the Office of Launch Vehicle Programs. Horner would be Chairman of the Council which would have its first meeting on January 28-29, 1960 (later changed to February 10-11, 1960).

1959 December 31 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- NASA approval of Saturn development program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Silverstein,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

NASA accepted the recommendations of the Saturn Vehicle Evaluation Committee Silverstein Committee on the Saturn C-1 configuration and on a long-range Saturn program. A research and development plan of ten vehicles was approved. The C-1 configuration would include the S-1 stage (eight H-1 engines clustered, producing 1.5 million pounds of thrust), the S-IV stage (four engines producing 80,000 pounds of thrust), and the S-V stage two engines producing 40,000 pounds of thrust.

1960 January 14 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Super booster program to be accelerated - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Eisenhower,

Glennan,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower directed NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan "to make a study, to be completed at the earliest date practicable, of the possible need for additional funds for the balance of FY 1960 and for FY 1961 to accelerate the super booster program for which your agency recently was given technical and management responsibility."

1960 January 28 - .

- NASA's Ten-Year Plan presented to Congress - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Glennan.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

In testimony before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Richard E. Horner, Associate Administrator of NASA, presented NASA's ten-year plan for 1960-1970. The essential elements had been recommended by the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight. NASA's Office of Program Planning and Evaluation, headed by Homer J. Stewart, formalized the ten-year plan.

On February 19, NASA officials again presented the ten-year timetable to the House Committee. A lunar soft landing with a mobile vehicle had been added for 1965. On March 28, NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan described the plan to the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences. He estimated the cost of the program to be more than $1 billion in Fiscal Year 1962 and at least $1.5 billion annually over the next five years, for a total cost of $12 to $15 billion. Additional Details: here....

1960 January - .

- Name Apollo suggested - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Gilruth,

Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

At a luncheon in Washington, Abe Silverstein, Director of the Office of Space Flight Programs, suggested the name "Apollo" for the manned space flight program that was to follow Mercury. Others at the luncheon were Don R. Ostrander from NASA Headquarters and Robert R. Gilruth, Maxime A. Faget, and Charles J. Donlan from STG.

1960 January - .

- Manned lunar landing and return (MALLAR) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Chance Vought Corporation completed a company-funded, independent, classified study on manned lunar landing and return (MALLAR), under the supervision of Thomas E. Dolan. Booster limitations indicated that earth orbit rendezvous would be necessary. A variety of lunar missions were described, including a two-man, 14-day lunar landing and return. This mission called for an entry vehicle of 6,600 pounds, a mission module of 9,000 pounds, and a lunar landing module of 27,000 pounds. It incorporated the idea of lunar orbit rendezvous though not specifically by name.

1960 February 1 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Lunar Exploration Program Based Upon Saturn Systems - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency submitted to NASA the study entitled "A Lunar Exploration Program Based Upon Saturn-Boosted Systems." In addition to the subjects specified in the preliminary report of October 1, 1959, it included manned lunar landings.

1960 February 10-11 - .

- NASA Space Exploration Council - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The first meeting of the NASA Space Exploration Council was held at NASA Headquarters. The objective of the Council was "to provide a mechanism for the timely and direct resolution of technical and managerial problems . . . common to all NASA Centers engaged in the space flight program." Additional Details: here....

1960 February 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Lunar Program Based on Saturn Systems - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing. Study issued by Huntsville of lunar landing alternatives using Saturn systems. Huntsville transferred from Army to NASA. Vought study on modular approach to lunar landing. Internally NASA decides on lunar landing as next objective after Mercury..

1960 February 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Eleven companies submitted contract proposals for the Saturn second stage - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Eleven companies submitted contract proposals for the Saturn second stage (S-IV): Bell Aircraft Corporation; The Boeing Airplane Company; Chrysler Corporation; General Dynamics Corporation, Convair Astronautics Division; Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc.; Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation; Lockheed Aircraft Corporation; The Martin Company; McDonnell Aircraft Corporation; North American Aviation, Inc.; and United Aircraft Corporation.

1960 March 1 - .

- NASA established the Office of Life Sciences Programs - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA established the Office of Life Sciences Programs with Clark T. Randt as Director. The Office would assist in the fields of biotechnology and basic medical and behavioral sciences. Proposed biological investigations would include work on the effects of space and planetary environments on living organisms, on evidence of extraterrestrial life forms, and on contamination problems. In addition, the Office would arrange grants and contracts and plan a life sciences research center.

1960 March 3-5 - .

- Advanced manned space flight program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

At a NASA staff conference at Monterey, Calif., officials discussed the advanced manned space flight program, the elements of which had been presented to Congress in January. The Goddard Space Flight Center was asked to define the basic assumptions to be used by all groups in the continuing study of the lunar mission. Some problems already raised were: the type of heatshield needed for reentry and tests required to qualify it, the kind of research and development firings, and conditions that would be encountered in cislunar flight. Additional Details: here....

1960 March 8 - .

- Preliminary guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. STG formulated preliminary guidelines by which an "advanced manned spacecraft and system" would be developed. These guidelines were further refined and elaborated; they were formally presented to NASA Centers during April and May..

1960 March 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I transferred to NASA. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Development Operations Division and the Saturn program were transferred to NASA after the expiration of the 60-day limit for congressional action on the President's proposal of January 14. (The President's decision had been made on October 21, 1959.) By Executive Order, the President named the facilities the "George C. Marshall Space Flight Center." Formal transfer took place on July 1.

1960 Spring - .

- Chance Vought study of the lunar orbit rendezvous method - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, Apollo Lunar Landing, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. Thomas E. Dolan of the Chance Vought Corporation prepared a company-funded design study of the lunar orbit rendezvous method for accomplishing the lunar landing mission..

1960 March 28 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Two H-1's fired together. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Two of Saturn's first-stage engines passed initial static firing test of 7.83 seconds duration at Huntsville, Ala..

1960 April 1-May 3 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

STG's Robert O. Piland, during briefings at NASA Centers, presented a detailed description of the guidelines for missions, propulsion, and flight time in the advanced manned spacecraft program:

- The spacecraft should be capable ultimately of manned circumlunar reconnaissance. As a logical intermediate step toward future goals of lunar and planetary landing many of the problems associated with manned circumlunar flight would need to be solved.