Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Man-In-Space-Soonest

Project 7969 Designs

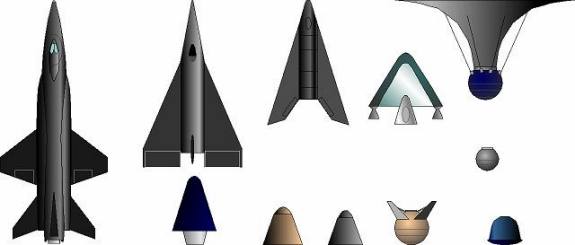

Project 7969 designs. From left, top row: North American X-15B; Bell Dynasoar; Northrop Dynasoar; Republic Demi body; Avco manoeuvrable drag cone. Second row: Lockheed; Martin; Aeronutronics; Goodyear; McDonnell; Convair

Credit: © Mark Wade

First Launch: 1958-04-24. Last Launch: 1958-04-24. Number: 1 .

Within a month the ARDC had established two research projects. The Manned Glide Rocket Research System would be a rocket-boosted winged follow-on to the X-15 that would reach 120 km altitude and Mach 21 - orbital velocity. The Task 27544 Manned Ballistic Rocket Research System would be a re-entry capsule, boosted by an ICBM, which would allow quick reaction delivery of critical cargo to any point on earth in less than an hour - or place a man in orbit. It was recommended that the second alternative be pursued as a priority, since development of re-entry vehicles and the Atlas ballistic missile would allow the first manned flight by 1960. It was seen as important to establish Air Force priority in this field since von Braun's Army team at Huntsville was known to be making similar proposals for rocket-powered troop transport.

In order to protect its precedence ARDC briefed the classified projects to the USAF Western Development Division (later the Ballistic Missile Division, BMD), in Inglewood; the Wright Air Development Center, in Dayton; the NACA at Langley; the prime aircraft contractors; and the American Rocket Society. In the absence of any funding from headquarters, ARDC had to rely on the contractors to invest their own funds in feasibility studies. McDonnell, a small aircraft company seeing a future business opportunity, began work in March 1956. Avco, the lead USAF contractor for ICBM re-entry vehicles, produced its first study by November 1956.

BMD formulated a long-range plan for Air Force dominance in space. On 29 July 1957 presentations were made at the Rand offices to the Air Force Scientific Board on competing concepts from ARDC and BMD. BMD had ambitious plans that extended to lunar flight (which would evolve into Project Lunex), while ARDC stuck to its two short-term projects. NACA's interest was confined to the Manned Glide Rocket Research System. They proposed a raised-top, flat-bottom glider configuration in a September 1957 feasibility report.

Russia launched Sputnik 1 on 4 October, creating a political furor and giving new priority and urgency to the military's space efforts. On 15 October the NACA held a technical conference to resolve the final configuration for the Manned Glide Rocket Research System. The agreed delta-winged flat-bottom configuration would evolve into the X-20 Dyna-Soar.

On 20 November Avco issued its second report, advocating a spherical manned reentry capsule brought down from orbit by a shuttlecock-like steel drag brake. Harrison Storms of North American conceived of a way to get an American into space as quickly as possible. North American had a warehouse full of partially-completed G-38 boosters for the just-canceled Navaho missile program. Storms proposed to cluster four of them together in order to launch an orbital version of the company's X-15 manned rocketplane. From the ARDC's point of view, the problem with either approach was the appalling reliability of either of these rocket boosters. The Atlas had only been launched twice so far, and not made it to burnout without veering off course. The Navaho G-38 had never been launched, although the prototype G-26 boosters were finally looking reliable on the last three flights after catastrophic results on the first four.

The ARDC still had no funds for research work, but the political furor over the Sputnik surprise mounted. Air Force efforts to do something were frustrated by the Eisenhower administration's disinterest in expanding the military-industrial complex into the space - at literally astronomical cost. An emergency committee chaired by physicist Edward Teller had proposed on 28 October that a crash space program, run by the Air Force, should be undertaken immediately. On 3 December Eisenhower's officially-sanctioned "civilian" satellite vehicle, the Vanguard, exploded on the pad on its first orbital launch attempt. But when the Air Force created a Directorate of Astronautics on 10 December, it was derided by Secretary of Defense McElroy and shut down three days later. No funds were forthcoming for either the Avco or North American proposals.

Headquarters USAF nevertheless ordered ARDC to prepare a comprehensive five year astronautics program. This was delivered to the Pentagon on 30 December. The plan foresaw development of reconnaissance, communications, and weather satellites, using recoverable data capsules. The manned program would begin with a manned capsule test system, followed by space stations, and an Air Force base on the Moon. Funding required would be $1.7 billion in FY 1959 alone.

Although this plan stalled in the offices of the civilian management of the Pentagon, the ARDC pushed ahead at full speed. On 20 to 31 January 1958 ARDC held a secret conference at Dayton where eleven airframers briefed their concepts for the first American manned spacecraft. There seemed to be a consensus that the basic Atlas ICBM alone was incapable of boosting sufficient payload to orbit for a manned capsule. The Atlas with an upper stage would be required. Most contractors proposed using the Hustler (later Agena) upper stage. This secret Lockheed vehicle was already under development for the deep black Corona reconnaissance satellite. A few contractors suggested using a solid propellant upper stage with the Atlas or he two-stage Titan-I booster. Only North American dissented, still advocating its cluster-of-Navaho-booster approach. Avco presented its drag-brake capsule concept, boosted by a Titan I. Lockheed, Martin, Aeronutronics, McDonnell, and Goodyear all advocated simple ballistic capsules of various forms, boosted by an Atlas with an upper stage. Bell and Northrop rejected the ballistic approach, one of them saying that a capsule 'would be only a stunt', and presented their Dyna-Soar designs. Republic presented the Ferri sled, a weird lifting vehicle.

On the last day of the conference, ARDC directed Wright Field to ignore the lifting concepts and concentrate on the fastest way of getting a man into space. BMD was to advise on the booster system to be used to accomplish that task. Overnight after the conference, von Braun's team launched the first US satellite using an Army Redstone booster. The Air Force was not only behind the Soviets, it was behind the Army. The first request for purchasing action, for a 24-hour environmental control system for the capsule, was issued a few days later.

The ARDC boiled down the 11 proposals to the three that had the best chance of quick realization - North American's X-15B, acceleration of the nascent program for the X-20 Dynasoar winged space glider, or one of the simple ballistic capsule designs, boosted by an existing launch vehicle. On 27 February they took these straight to Curtis LeMay, Air Force Vice Chief of Staff and former head of the Strategic Air Command. LeMay's main comment was: "Where's the bomb bay?" Nevertheless, he instructed ARDC to select one of the concepts and submit a detailed plan for an Air Force man-in-space program as soon as possible.

The next day, Roy W Johnson, former vice-president of General Electric and now head of the Pentagon's new Advanced Research Project Agency (ARPA), affirmed that "the Air Force has a long term development responsibility for manned space flight capability with the primary objective of accomplishing satellite flight as soon as technology permits." On 8 March BMD proposed an 11-step "Manned Space Flight to the Moon and Return" program. This began with instrumented and primate orbital missions, followed by a manned orbit of Earth; circumnavigation of the Moon, first with instruments, then primates; instrumented hard and soft landings on the Moon; a primate landing on the Moon; manned lunar circumnavigation; and a manned lunar landing.

On 10-12 March ARDC held a conference at BMD of 80 technical and biological specialists. The objective was to reach agreement on a plan to get a man-in-space - soonest - in accordance with LeMay's orders. Unfortunately for North American's X-15B, the consensus at the conference was that the "quick and dirty" approach was best. This would consist of a simple ballistic capsule using parachutes for a water landing, weighing around 1300 kg. The capsule would be 1.8 m in diameter and 2.4 m long, and completely automated - the human-factors people felt there was no certainty that a pilot could function under the stresses of space flight. This last point ruled out the piloted X-15B.

The capsule's life support system would be designed for single-crew missions of up to 48 hours. The preferred re-entry vehicle was the 'Discoverer' type being developed for the Corona project. For this kind of capsule, where the direction of G-forces was reversed between ascent and return, the pilot's couch proposed by Harold J von Beckh of ARDC's Aeromedical Field Laboratory was necessary. This was attached at pivot points at the head and feet of the pilot, so it would rotate freely to bring the pilot's back against the G forces, regardless of their direction. An ablative heat shield would allow re-entry deceleration to be kept below 9 G's, and the cabin temperature below 65 deg C. Multiple small solid propellant retro-rockets would brake the capsule back into the atmosphere at the end of its mission.

Nobody advocated using the Atlas alone as the booster. The medical specialists concluded that the occupant might be subjected to 20-G's in an abort from the Atlas, believed to be beyond the limit of human tolerance, whereas a two-stage vehicle would limit that to an acceptable 12-G's. Space Technology Laboratories, technical advisor to the Air Force for the ICBM program, believed the Atlas would be too unreliable. They favored using the Thor IRBM with the Nomad fluorine-hydrazine upper stage. A development program was sketched out, requiring flight of 10 Thor-Ables for initial tests and primate flights, to be followed by 20 Thor-Nomad flights. While all this was going on, NACA management was still committed to winged orbital flight, and had not participated in the Air Force capsule discussions. It was not until three days after the conference that NACA agreed to support the effort, although it declined to jointly manage the project with the Air Force.

ARDC sent its crash development plan for a manned orbital capsule to Headquarters USAF on 14 March. Based on this, on 19 March, the Air Force requested $133 million from ARPA for the program in FY 1959. While the Air Force was charging forward, Eisenhower had numerous high-level studies underway, all with the objective of preventing the extension of the military into space. He also approached the Russians on calling off the space race altogether, but got nowhere.

NACA held its own internal conference on manned spacecraft on 18 March at Ames at Moffett Field. Faget led the Langley majority group, advocating a ballistic capsule. This would be semi-conical, 2.13 m in diameter, 3.35 m long, using a heat sink heat-shield. The advantage over the Discoverer-type re-entry vehicle was that the pilot's seat would not have to pivot. The design was aerodynamically unstable compared to the self-righting Discoverer design, but attitude control jets were believed to be sufficient to keep the capsule from oscillating uncontrollably during re-entry.

John Becker from Langley offered a winged configuration, which would re-enter at a high angle of attack, using its flat under-side as a heat shield. He argued that a one-man vehicle would weigh 1390 kg, not significantly heavier than Faget's ballistic capsule, while limiting re-entry deceleration to 1 G.

The Ames concept was the blunt M-1 lifting body that the center had been refining for many months. This was a compromise between the pure ballistic and winged vehicles. Reentry deceleration would be kept to 2-G's, and the pilot could remain in control at all times.

All of these NACA discussions were held in a vacuum regarding the launch vehicle. It was felt that waiting for development of a two-stage vehicle would take too long; the Atlas ICBM alone should be sufficient. But no one at NACA had the 'need to know' to gain access to the classified performance characteristics of the Atlas.

Within ARDC a Man-in-Space Task Force was set up at BMD. While the final goal was to "… to land a man on the moon and return him safely to earth," the first phase was "Man-in-Space-Soonest." This was the program sketched out in March, and used the Thor-Nomad vehicle. Once the first human had been orbited, MISS-1 would be followed by MISS-2 - "Man-in-Space-Sophisticated". This would use a heavier version of the same capsule, demonstrating manned flight up to the 14-days required for a voyage to the moon and back. Phase 3, "Lunar Reconnaissance," would soft-land an unmanned probe equipped with a television camera on the lunar surface, to prove landing techniques and verify the nature of the lunar surface. Phase 4, "Manned Lunar Landing and Return," MALLAR, would orbit primates, then men, around the moon; and then land primates, and then men, on the moon and return them to earth. For the Phase 4 lunar flights a Super Titan launch vehicle, using fluorine-oxidizer second and third stages, would power the spacecraft toward the moon.

By 2 May the task force forwarded to Headquarters USAF the detailed designs, operational procedures, and schedule for Man-in-Space-Soonest. The Thor-Agena/WS-117L, Thor-Able, and Thor-Nomad boosters would be used. The first manned flight would be made on the tenth launch of the Thor-Nomad, in October 1960. The capsule had an abort system that used high-thrust solid fuel rockets at the base of the capsule to fire it clear of the booster in case of an emergency.

But suddenly there was a three-week delay. Avco had gotten back together with Convair, and on 30 April they back-doored to LeMay a convincing and highly detailed proposal for development of their minimum vehicle. This used the Atlas without an upper stage, and the same Avco drag brake design they had been working on for two years. Even BMD, which hated the idea of using the "bare" Atlas, had to admit it would save four months in development time. But ARDC, advised by Faget at NACA, still favored the simple ballistic capsule with a parachute landing. Therefore on 20 May, Lieutenant General Samuel E Anderson, Commander of ARDC, replied to LeMay that he had no confidence in Avco's design, and recommended that the Air Force proceed as per the 2 May plan. LeMay accepted the response, and the program lurched back into gear.

But ARPA was still reluctant to provide the $133 million required to start development. They felt the development of the Thor-Nomad would take longer than planned, and possibly require 30 vehicle launches rather than 20, causing a massive cost escalation. Convair convinced Air Force Under Secretary MacIntyre and Assistant Secretary Richard E Horner that using Atlas instead could cut the program cost below $100 million. BMD grumbled that this would mean cutting the orbital altitude of the 900 to 1360 kg capsule from 275 km to 185 km, leaving the capsule out of range of the tracking network for much of the time. Nonetheless they submitted a revised plan on 15 June, using the Atlas and bringing the budget to $99.3 million while moving up first manned flight to April 1960.

With these changes ARPA released modest budget funds for initial study contracts for MISS-1. Convair had won the booster race, but Avco was out of the running on the spacecraft. Up to this point McDonnell had invested more work than any other contractor on designing the spacecraft. They had over 70 staff working full-time on it, at their own expense. They had consulted extensively with Faget at Langley to keep abreast of NACA's latest information on capsule design. Therefore it was quite a blow when, on 16 June, Wright Field issued competitive design study contracts to North American and General Electric for the capsule. Each contract was nominally valued at $370,000 and was to run for three months. Each contractor was to complete design of the capsule and present a mock-up of their planned spacecraft. A down-select would be made in September, once fiscal year 1959 had begun.

On 25 June the Air Force completed a preliminary astronaut selection for the project. The list was prioritized according to the weight of the pilot due to the low payload available. The 150-175 pound group consisted of test pilots Bob or Robert Walker, Scott Crossfield, Neil Armstrong, and Robert Rushworth. In the 175 to 200 pound group were William Bridgeman, Alvin White, Iven Kincheloe, Robert White, and Jack McKay. It was the first astronaut selection in history. (Most historians assume the Bob Walker listing is an error for X-plane pilot Joseph Walker, although a Captain Robert P Walker, USAF, did graduate in the Edwards test pilot school class 54-C on 17 January 1955, together with Robert White).

While all of this was going on Eisenhower's plan to create a civilian space agency had developed into legislation, which was working its way through Congress. ARPA was not willing to put too much ARPA money into what might be another agency's project. Herbert York at ARPA put the brakes on by replacing the USAF's swift decision-making with committees and studies. He decided NACA would have to start clearing important decisions. An ARPA coordination meeting on 25-26 June with representatives from ARDC, BMD, Convair, Lockheed, Space Technology Laboratories, and NACA failed to reach a decision on the payload capability of the Atlas for the mission, the reliability, or on the use of a heat sink or ablation heat shield. They even started studying other booster possibilities. ARPA still withheld formal release of funds for the full-scale development program.

While all of this was going on, NACA Langley, expecting to receive the project in FY 1959, worked independently to complete its own in-house manned capsule design. The original flat-bottomed concept of March was refined, first to the Soyuz-like configuration that McDonnell was working on, and finally to the rounded-bottom, conical configuration finally adopted for the Mercury capsule. Faget continued to work closely through the back door with McDonnell despite the fact that the USAF had already down-selected to North American and General Electric.

On 10 July Brigadier General Homer A Boushey of Headquarters USAF informed ARDC that Eisenhower's Bureau of the Budget, firmly in favor of placing the manned space flight program in the new civilian agency, was blocking further release of funds for the program. On 16 July the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 was passed by Congress, and NASA was created out of the NACA and some Army and Navy rocket laboratories. But ARPA told the Air Force there was still a chance the White House would support MISS if costs could be kept to under $50 million in FY 1959. They could present the project as so far along, and with so low a cost to complete, that it would be a big setback to start all over with NASA.

But BMD couldn't make the figures come out this way. Funding of only $50 million in FY 1959 would delay the first American in space to early 1962. Instead, on 24 July, General Bernard Schriever at BMD issued the sixth revision to the MISS development plan. This had a total cost of $106.6 million with the bare Atlas as the booster. Salient features included establishment of a worldwide tracking network, resolving quickly the heat sink versus ablation heat shield issue, and continuing with design of the Thor WS-117L and Thor-Able as backups in case the Atlas proved to be unreliable. Assuming immediate authorization from ARPA, Schriever promised release of the final tender documents to the contractors within 24 hours, and orbiting of the first man in space by June 1960.

The next day there was one last session with ARPA Director Johnson at the Pentagon. BMD pointed out that only full, unrestricted, immediate program approval to go ahead with MISS would give the United States a real chance to be "soonest" with a man in space. Johnson flatly refused. Eisenhower saw no valid role for the military in manned space flight. NACA didn't plan to spend more than $40 million on their manned space program in FY 1959, fiscally much more attractive than the $107 million the Air Force was asking for.

On that day - 25 July 1958 - America gave up its chance to put the first man into space. A manager like Schriever could undoubtedly have rammed the project through on the promised schedule. The collection of scientists and tinkerers at NACA had no chance.

Air Force participation in what was now a NASA program continued briefly. It was not quite clear that the new civilian agency would be given the lead in the manned space capsule program. Harrison Storms at North American was informally told he would be given the MISS capsule contract. In mid-September, action was replaced by a committee - a joint NASA-ARPA Manned Satellite Panel to draw up recommendations. NASA became operational on 30 September 1958, and the Air Force took only a logistical support role in the new program.

NASA ran a new competition for the manned capsule, which was to be produced to Faget's precise specifications. McDonnell, which had worked so closely with Langley, unsurprisingly won the award in January 1959. NASA would spend over $400 million on Mercury, but not fly the first American in orbit aboard an Atlas until February 1962. McDonnell's corporate commitment, preparation, and kowtowing to Faget's preferences were noted by Harrison Storms at North American. He vowed not to make the same mistake again. Four years later he convinced North American's management to take the same approach, and won the biggest plum of all, the Apollo moon-landing contract.

| Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1959. North American was the final selected vendor for Manned-In-Space-Soonest. The 1360-kg ballistic capsule would be launched by an Atlas booster to an 185-km altitude orbit. |

| Aeronutronics Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Aeronutronics' proposal for the Air Force initial manned space project was a cone-shaped vehicle 2.1 m in diameter with a spherical tip of 30 cm radius. It does not seem to have been seriously considered. |

| Avco Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. AVCO's proposal for the Air Force initial manned space project was a 690 kg, 2. |

| Bell Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Bell's preferred concept for the Air Force initial manned space project was the boost-glide vehicle they had been developing for the Dynasoar program. |

| Convair Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Convair's proposal for the Air Force initial manned space project involved a large-scale manned space station. When pressed, they indicated that a minimum vehicle - a 450 kg, 1. |

| Goodyear Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Goodyear's proposal for the Air Force initial manned space project was a 2.1 m diameter spherical vehicle with a rearward facing tail cone and ablative surface. |

| Lockheed Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Lockheed's proposal for the Air Force initial manned space project was a 20 degree semiapex angle cone with a hemispherical tip of 30 cm radius. The pilot was in a sitting position facing rearward. |

| Martin Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Martin's proposal for the Air Force manned space project was a zero-lift vehicle launched by a Titan I with controlled flight in orbit. The spacecraft would be boosted into a 240 km orbit for a 24 hour mission. |

| McDonnell Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. McDonnell's design for the Air Force initial manned space project was a ballistic vehicle coordinated with Faget's NACA proposal and resembling the later Soviet Soyuz descent module. |

| Northrop Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Northrop's proposal for the Air Force initial manned space project was a boost-glide vehicle based on work done for the Dynasoar project. |

| Project Mer American manned spacecraft. Study 1956. April 1958 design of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics for a Manned Earth Reconnaissance spacecraft - consisting of a cylindrical fuselage and telescoping, inflatable wings for flight in the atmosphere. |

| Republic Project 7969 American manned spacecraft. Study 1958. Republic's studies for the Air Force or NACA initial manned space project started at the beginning of 1958. Their unique concept was a lifting re-entry vehicle, termed the Ferri sled. |

| MISS Flight 1 In the USAF Man-In-Space Soonest program plan issued on 15 June 1958 targeted the first manned flight for April 1960. Ten days later the first astronaut group was identified - consisting of Robert Walker, Scott Crossfield, Neil Armstrong, and Robert Rushworth. But a month later the project was stopped, and NASA was handed the program in September 1959. NASA's project Mercury wouldn't orbit an American until 1962. |

People: Bridgeman, White, Alvin, Walker, Joseph, Crossfield, McKay, White, Robert, Rushworth, Kincheloe, Armstrong. Country: USA. Launch Vehicles: Thor, Thor Able. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral LC17A. Bibliography: 491, 59, 7668.

1955 January 1 - .

- Military space projects under study. - .

Spacecraft Bus: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Lunex.

In 1955-1957 many Air Force officers in widely scattered field units, without coordinated effort, prepared papers and studies proposing military space projects. Small groups at Headquarters Air Research and Development Command, at the Ballistic Missile Division, at Holloman Air Force Base, and at Wright Air Development Center (WADC) sensed danger in the Government's unwillingness to give the new technology the urgent support they felt it deserved. Programs were proposed which called for organized space experiments, "at the earliest practicable date." Such experiments included orbiting satellites, manned and unmanned, a manned space station and a spacecraft voyage to the moon. (Bowen, Lee, The Threshold of Space, Sep 1960, published by the Air Force Historical Liaison Ofc, p.7)

1955 June 28 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas B.

- Quarles Committee studies best method of furnishing the United States with a sattelite by end of 1958. - .

Related Persons: Quarles,

Schriever.

Spacecraft Bus: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

SCORE.

Quarles Committee studies best method of furnishing the United States with a sattelite by end of 1958. A committee, appointed by Secretary of the Air Force, D. A. Quarles, to recommend the best method of furnishing the United States with a satellite between the dates of June and December 1958, was briefed at Western Development Division (WDD). The Atlas project was reviewed and the potential of Atlas as a booster vehicle in a selected satellite system was presented. The committee was advised that WDD was qualified to manage the program if so directed but that such a program would interfere, to some extent with the high priority of the Atlas development effort. (Memo, Col C. H. Terhune, Dep Cmdr Tech Opns, WDD, to Brig Gen B. A. Schriever, Cmdr WDD, 28 Jun 55, subj: Visit of DOD Satellite Committee, 28 Jun 55.)

1955 July 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Vanguard.

- USA to launch 10-kg satellite in 1958 without military missiles. - .

Spacecraft Bus: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Eisenshower announced that the USA would launch 10-kg satellites in 1958 without the use of military missiles. The President announced that the United States, as part of its International Geophysical Year contributions, would attempt to launch a number of 21 pound satellites without the use of military missiles. The project, named Vanguard, although organized in the Department of Defense under Navy management, would be completely removed from military significance. (Bowen, The Threshold of Space, p.10.)

1956 March - .

- Manned Ballistic Rocket Research System - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft Bus: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Spacecraft: Project 7969.

Project 7969, entitled 'Manned Ballistic Rocket Research System,' was initiated by the Air Force with a stated task of recovering a manned capsule from orbital conditions. By December of that year, proposal studies were received from two companies, and the Air Force eventually received some 11 proposals. The basis for the program was to start with small recoverable satellites and work up to larger versions. The Air Force Discoverer firings, which effected a successful recovery in January 1960, could be considered as the first phase of the proposed program. The Air Force program was based upon a requirement that forces no higher than 12g be imposed upon the occupant of the capsule. This concept required an additional stage on the basic or 'bare' Atlas, and the Hustler, now known as the Agena, was contemplated. It was proposed that the spacecraft be designed to remain forward during all phases of the flight, requiring a gimballed seat for the pilot. Although the Air Force effort in manned orbital flight during the period 1956-58 was a study project without an approved program leading to the design of hardware, the effort contributed to manned space flight. Their sponsored studies on such items as the life-support system were used by companies submitting proposals for the Mercury spacecraft design and development program. Also, during the 2-year study, there was a considerable interchange of information between the NACA and the Air Force.

1956 April 1 - .

- Army Ballistic Missile Agency requested permission to use its Jupiter C missile to launch a satellite. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Army Ballistic Missile Agency requested permission to use its Jupiter C missile to launch a satellite. The Army Ballistic Missile Agency requested that the Department of Defense grant permission to use its Jupiter C missile to launch a satellite, "in view of Vanguard delays and increasing evidence that the Soviets would be first in space--an event certain to inflict 'serious damage' to the prestige of the United States. The Army's proposal was rejected by the Department of Defense, presumably in line with the policy announced by the President on 29 July 1955, that the United States would remain strictly within its International Geophysical Year satellite commitment without using military missiles, thus clearly demonstrating United States intent to explore space for peaceful purposes. (Bowen, Threshold of Space, pp, 10-11.)

1956 May 1 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas Able.

- Rand Corporation studies a lunar instrument carrier, based on use of an Atlas booster. - . Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest. Rand Corporation issued a series of reports on the feasibility of a lunar instrument carrier, based on use of an Atlas booster. (Early BMD-ARDC General Space Chronology, II Feb 59, prep by AFBMD Hist Ofc.).

1956 October 3 - .

- USAF study urges military space program based on using ballistic missiles as boosters. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Western Development Division released a short study report entitled, "Ballistic Missiles, Satellites and Space Vehicles. " The paper recommended a detailed survey of technical developments which might anticipate "logical extensions of our present ballistic missile and satellite programs." Advanced systems were foreseen in the next 20 years which might well furnish equipment and technology for manned exploration of space including voyages to the moon and near by planets. The paper also recommended that the Air Force plan an orderly development of space programs aimed at these far reaching but reasonable long term objectives. (Paper, Ballistic Missiles, Satellites and Space Vehicles, 1956 to 1976, dtd 3 Oct 56, prep by Col L. D. Ely, Asst for Tech Groups, Tech Operations, WDD.)

1956 November 1 - .

- USAF recommends 1955-1970 program leading to manned interplanetary space exploration. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

USAF recommends 1955-1970 program for ballistic missiles, satellite reconnaissance systems, recoverable satellites, and manned interplanetary space exploration. Air Research and Development Command Guided Missile and Space Vehicle Committee report, based primarily on Western Development Division-Ramo -Wooldridge sources, contained a technological forecast (1955-1970) and program recommendations for ballistic missiles, satellite reconnaissance systems, recoverable satellites, manned interplanetary space exploration, and related facilities, funds and manpower requirements. It was estimated that program costs would reach $800 million by fiscal year 1961 and continue at a level of $500 million a year until 1970, then soar to $1.9 billion in 1971. (Early BMD-ARDC General Space Chronology, 11 Feb 59.)

1957 February 5 - . LV Family: Minuteman.

- USAF requests study of second generation ballistic missiles. - . Spacecraft Bus: Man-In-Space-Soonest. The Air Force authorized Ramo-Wooldridge (Guided Missile Research Division) to begin a study of second generation ballistic missiles and space vehicles. (Early BMD-ARDC General Space Chronology, 11 Feb 59.).

1957 July 29 - .

- Air Force presentation on space capabilities and plans. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Lunex.

Air Force Ballistic Missile Division (Western Development Division was redesignated Air Force Ballistic Missile Division, 1 Jun 1957) presented to the Scientific Advisory Board Ad Hoc Committee, meeting at Rand Corporation, a summary of follow on ballistic missile weapon systems and advanced space programs which it was prepared to undertake. These programs included development of high thrust space vehicles capable of earth orbital and lunar flights. (AFBMD Presentation to the Scientific Advisory Board Ad Hoc Committee to Study Advanced Weapons Technology and Environment, 29 Jul 57, prep by AFBMD.)

1957 October 9 - .

- Second generation ballistic missiles and military satellites - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Lunex.

Scientific Advisory Board Ad Hoc Committee urges development of second generation ballistic missiles and military satellite systems for reconnaissance, communications and weather. The Scientific Advisory Board Ad Hoc Committee on Advanced Weapons Technology and Environment published its review of "... problems of national defense in cislunar space, with particular regard to their impact on future weapons technology and the operating environment in which these weapons might function. " The committee report urged development of second generation missiles not only for their primary weapon system value but for their use as space boosters. The next priority, in the committee's analysis, was to develop military satellite systems for reconnaissance, communications and weather prediction. The Air Force should also plan on reaching the moon and, despite the failure of the committee to define any specific military application resulting from occupation of the moon, appropriate steps should be taken to develop a space technology to support advanced exploration of space. The committee was also concerned that, while it appeared to be the plan of the Air Research and Development Command to place all ballistic missile programs under the management of the Ballistic Missile Division, there was not yet " . . ar official understanding that Air Force Ballistic Missile Division is a permanent organization set up to cover this role into the future." The committee therefore urged that "... Air Force Ballistic Missile Division be recognized at the earliest possible date as a permanent organization for ballistic missiles and satellite projects. " (Rpt of the Scientific Advisory Board Ad Hoc Committee to Study Advanced Weapons Technology and Environment, 9 Oct 57.)

1957 October 15 - .

- US government officials attempted to belittle this Russian Sputnik. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Despite the focus of worldwide interest and public acclaim on the launch of Russian satellites (Sputnik I, 4 October; Sputnik II, 3 November) many high ranking government officials attempted to belittle this Russian scientific achievement. On 9 October the White House announced that the "United States would not become engaged in a space race with other nations and that Project Vanguard would not be accelerated." Nevertheless, the Secretary of the Air Force, James H. Douglas, called upon a committee of distinguished scientists and Air Force officers headed by Dr. Edward Teller to propose a line of positive action. The committee's report, completed 22 October, contained a strong recommendation for a unified program--a recommendation which was disregarded, "in favor of a divided program that, in the opinion of many, tended to dissipate rather than concentrate the expanded effort. " (Bowen, Threshold of Space p. 13.)

1957 November 5 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF briefed the Armed Forces Policy Council on a reconnaissance satellite program. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The Air Force briefed the Armed Forces Policy Council on a reconnaissance satellite program and possible combinations of vehicles that could be used for "cold war and scientific programs." The Air Force recommended using the available intermediate range ballistic missile as a booster to hasten launching an orbital system as early as March 1958. If approved this program would require an additional six Thors and $12 million to cover additional costs. (Ltr, Co0 R. J. Nunzia.o, Asst for Spec Prog, DCS/Dev, Hq USAF, to SAFRD, 12 Nov 57, subj: Outer Space Vehicle.)

1957 November 7 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- Three Thor IRBM's to be diverted for an early satellite capability. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Three Thor IRBM's to be diverted from the missile test program and used for an early satellite capability. In response to the nation's urgent need to demonstrate at least an early space vehicle capability it was suggested that three Thor boosters be made available from the missile test program and from these an early satellite or space capability could be obtained. Accordingly, Air Force headquarters requested Air Research and Development Command to conduct an engineering study which would " . . . provide sufficient information to this headquarters within the next 30 45 days on which a decision can be based as to the feasibility, capability and cost of such a program. " An immediate release of $100,000 enabled the command to fund preliminary design studies. (Msg, 11-033, ARDC to AFBMD, 13 Nov 57.)

1957 November 12 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- Crash space program using the Thor IRBM as the booster. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

USAF requested the Department of Defense approve a crash space program using the Thor IRBM as the booster. Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Research and Development, R. E. Horner, requested the Department of Defense approve a space program that would furnish an early demonstration of space capability and "provide important development test vehicles leading to larger reconnaissance and scientific satellites." To hasten action three Thor missiles, 114,116 and 118 ". . could be made available in a relatively short period of time with minimum interference to the IRBM program. " These boosters could be used to orbit a recoverable animal satellite prior to 1 July 1958. Thor, it was also suggested, would be a practical vehicle to furnish the Air Force satellites with specific military capabilities. (Memo, Asst SAF (R&D), R. E. Homer, to SOD, 1Z Nov 57, subj: Outer Space Vehicle.)

1957 November 13 - .

- Plan for a program leading to the development of man-carrying vehicle systems for space operation. - . Related Persons: Schriever. Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest, Lunex, . Major General Bernard A. Schriever, AFBMD Commander, directed preparation of a plan for a program leading to the development of man-carrying vehicle systems for space operation..

1957 November 13 - .

- USAF to prepare a plan for a 15 year program of manned space exploration. - .

Related Persons: Schriever.

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Major General B. A. Schriever, Commander of Air Force Ballistic Missile Division directed preparation of a plan for a 10 15 year program leading to development of man carrying vehicle systems for space exploration. A preliminary plan for an orderly space development effort and ultimate manned flight had, in fact, already been prepared and awaited presentation to General S. E. Anderson, Commander of Air Research and Development Command. The plan envisioned manned space flight with a minimum of new development through the use of existing knowledge, experimental programs, missile-boosters, and facilities available throughout the command. (Memo, Col L. D. Ely, Dir Tech Divs, Weapon Systems, AFBMD, to Col C. H. Terhune, Dep Cmdr, Weapon Systems, AFBMD, 13 Dec 57, subj: Manned Space Flight Program; Cmdrs Reference Book, Chronology of Man in Space Effort, 23 Mar 59, prep by AFBMD.)

1957 November 20 - .

- USAF studies human spaceflight requirements. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Air Force Missile Development Center (AFMDC) was investigating vital environmental elements applicable to manned space flight. One of two technical development projects was titled, "Human Factors of Space Flight. " The investigation covered exposure to space radiation, tolerance to high g loads and weightlessness, problems of descent and recovery from space, and physical and environmental problems of sealed cabins. A second study, "Biodynamics of Human Factors for Aviation", investigated tolerance to abrupt deceleration, total pressure changes, abrupt wind blasts and aircraft crash forces. These studies were symptomatic of a renaissance of scientific interest in space research throughout the Air Research and Development Command. (Memo, Maj D. L. Carter, Dep Dir, Tech Div, Weapon Sys, AFBMD, to Col C. H. Terhune, Dep Cmdr, Weapon Sys, 19 Dec 57, subj: Meeting With Major Simons, AFMDC.)

1957 November 20 - .

- USAF to acquire recognized competence in astronautics and space technology. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Air Force headquarters affirmed the necessity for the Air Force to acquire recognized competence in "astronautics and space technology." Therefore the Air Research and Development Command was instructed to prepare by 1 December 1957 an astronautics program with estimates of its funding requirements. The plan was to review those space programs already underway and make a projection of development in astronautics and space technology over the next five years. (Msg, Cmdr ARDC, to Comdr AFBMD, 20 Nov 57.)

1957 November 26 - .

- Parameters to be set for 15-year USAF manned space program. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Air Research and Development Command began a strong effort to orient the work of the command to meet accelerating demands of space technology. A Ballistic Missile Space Vehicle Working Group, appointed by the Commander on 18 January 1957, was convened to establish "new Research and Development Parameters for the Technical Program. " The group's work, essentially, was to predict Air Force space vehicle requirements and developments over the next 15 year time period. (Ltr, Col R. V. Dickson, Asst Dep Cmdr (R&D), to Cmdr AFBMD, 26 Nov 57, subj: Ballistic Missile/Space Vehicle Working Group.)

1957 December 6 - .

- USAF recommends vigorous space program with immediate goal of landing on the moon. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The Air Force Scientific Advisory Board Ad Hoc Committee on Space Technology recommended, because "Sputnik and the Russian ICBM capability have created a national emergency, " acceleration of specific military programs and a vigorous space program with the immediate goal of landings on the moon. (Rpt, SAB Ad Hoc Committee on Space Technology, 6 Dec 57.)

1957 December 9 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan I.

- AVCO Corporation proposed development of a manned satellite system to the Air Force. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The basic elements of the proposal included a Titan rocket to boost a manned satellite into a 110 nautical mile earth orbit. The satellite would be a spherical capsule containing instrumentation and a life support system capable of sustaining one man for three or four days. A novel feature of the system would be development of a stainless steel cloth parachute which would lower the capsule safely through re-entry deceleration. As the air pressure increased the parachute would automatically expand to its full size and land the capsule at a survival, if bone jarring, rate of 35 feet per second. AVCO asked $500,000 for a three month study and mockup of the capsule device and estimated, as a rough guess", a total development cost of $100 million. The ballistic missile division, however, was not convinced that this was the best approach to the manned reentry problem. The division' s position was that when the Air Force identified its space goals and established specific technical requirements it would then be wiser to "ask for bids and put it (development) on an open competitive basis. " (Memo, Col L. D. Ely, to Col C. H. Terhune, 17 Dec 57, subj: AVCO Proposal for Manned Satellite.)

1957 December 10 - .

- USAF to increase space research funding by 50 percent. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Although the tempo of space technology research within recent months had been significantly accelerated by the Air Research and Development Command, a further increase was yet desirable. A plan, which would increase space research by 50 percent or more by fiscal 1959 and place management responsibility for the over-all space technology program within command headquarters, now adopted. (Ltr, Lt Gen S. E. Anderson, Cmdr ARDC, was to Cmdr AFMDC, 10 Dec 57, subj: Space Technology.)

1957 December 10 - .

- USAF establishes Directorate of Astronautics. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Lieutenant General D. L. Putt, Deputy Chief of Staff Development at Air Force headquarters, announced establishment of the Directorate of Astronautics, to be headed by Brigadier General Homer A. Boushey. There was, however, an adverse Department of Defense reaction to this action. The Secretary of Defense objected to the use of the term "astronautics" and William Holaday, Defense Director of Guided Missiles, publicly stated the Air Force "wanted to grab the lime light and establish a position. " Just three days later General Putt directed that the organizational change be cancelled. (Bowen, Threshold of Space, p. 20.)

1957 December 16 - .

- Space technology development to be managed by the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The Scientific Advisory Committee to the Secretary of the Air Force met at the ballistic missile division. The committee reviewed Air Force plans for advanced ballistic missile and space programs and recommended that space technology development be managed by the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division. (Early BMD-ARDC General Space Chronology, 11 Feb 59, prep by AFBMD Hist Ofc.)

1957 December 18 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF proposes accelerated astronautics program for 1958-1959. - .

Related Persons: Schriever.

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Major General B. A. Schriever again offered a well defined astronautics program at an estimated cost of $16 million in fiscal 1958 and $112 million in 1959. In addition, $10 million in 1958 and $2O million in 1959 would be needed to procure Thor hardware and acquire a Thor space launch complex. Furthermore, said Schriever, although use of all resources qualified to participate in the program was endorsed it was ". . . imperative that the total Air Force effort in the ballistic missile and space field must be managed by one agency and that agency must be the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division. " Schriever also proposed creation of a research and development command committee, chaired by the missile division, to formulate and recommend technical development in space technology. "The committee would meet periodically and make recommendations to the commander, AFBMD, for formulation of the Air Force program." "(Ltr, Maj Gen B. A. Schriever, Qmdr AFBMD, to Lt Gen S. E. Anderson, Cmdr ARDC, 18 Dec 57, subj: Proposal for Future Air Force Ballistic Missile and Space Technology Development.)

1957 December 20 - .

- The technical program of the Air Force reoriented toward state of the art development. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The technical program of the Air Force research and development structure was being reoriented toward state of the art development. This would "..... provide the United States significant capabilities in the area of space technology. " Air Force Ballistic Missile Division was instructed to review and revise its technical programs to insure that they were contributing to the development of a sound space technology. (Ltr, Maj Gen J. W. Sessums, V/Cmdr ARDC, to Cmdr AFBMD, 20 Dec 57, subj: Space Technology.)

1957 December 27 - .

- USAF ready to undertake manned space program. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

An appraisal of Air Research and Development Command research and engineering resources revealed that the command was well prepared to undertake immediate development of a manned space program. The ballistic missile division possessed the resources to embark on vehicle development and command headquarters was ready with a " . . . Fairly comprehensive program laid out in support of the manned aspects of space flight. " In specific terms this involved support from the School of Aviation Medicine, the Aeromedical Laboratory at Wright Air Development Center (WADC), and the Aeromedical Field Laboratory at AFMDC. (Memo, Col L. D. Ely, to Col C. H. Terhune, 30 Dec 57, subj: Telephone Call from General Flickinger and Visit of Colonel Karstens, School of Aviation Medicine.)

1957 December 30 - .

- USAF 15 year plan for astronautics - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

USAF Air Research and Development Command completed a 15 year plan for astronautics research and technical development. From this effort was distilled a five year astronautics program which, on this date, was presented to Air Force headquarters. (Ltr, Brig Gen M. C. Demler, D/Cmdr, R&D, Hq ARDC, to Cmdr AFBMD, 30 Dec 57, no subject.)

1957 December 31 - .

- USAF astronautics program under review. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The astronautics program "package" was under review by Air Force headquarters. Some additional data from AFBMD was requested - cost information, amount of money needed to perform specific tasks and the desirable priority to be assigned each task. (MFR, Brig Gen 0.J. Ritland, V/Cmdr, AFBMD, 31 Dec 57, subj:. Telephone Call from Col Nunziato.)

1958 During the Year - .

- Project Mer - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft Bus: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Spacecraft: Project Mer.

The Navy space proposal to the Advanced Research Projects Agency, during the tenure of that organization's interim surveillance over national space projects, was known as Project Mer. This plan involved sending a man into orbit in a collapsible pneumatic glider. The glider and its occupant would be launched in the nose of a giant launch vehicle. After the glider had been placed in orbit, it would be inflated, and then flown down to a water landing.

1958 January 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF recommendation for a strong astronautics program, including animal and lunar flights. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Air Force Ballistic Missile Division's recommendation for a strong astronautics program, forwarded to Lt General D. L. Putt, Deputy Chief of Staff, Development, at Air Force headquarters, included the following specific proposals: (1) Thor plus a Vanguard second stage would be used as the basic booster to provide a vehicle with a recoverable data capsule: first orbital flight with telemetry only by September 1958, followed by four additional flights during the remainder of fiscal 1959. (2) Develop a recoverable animal carrying satellite using rhesus monkeys; four flights during fiscal 1959. (3) Lunar impact missions could be attempted with a high probability of success by adding a Vanguard third stage to the Thor and Vanguard second stage vehicle; four vehicles should be planned for this mission beginning during the last quarter of 1958, (4) Four vehicles should be assigned the mission of circumlunar flight. Total cost of these programs was estimated at $26.8 million during fiscal 1958, and $30.4 million in fiscal 1959 including ground equipment and Thor production would have to be increased by two units per, month if the entire astronautics program were adopted as proposed. (Msg, WDG-I -Z, Cmdr AFBMD, to Cmdr AIDC, 3 Jan 58.)

1958 January 9 - .

- Secretary of Defense McElroy intentions to create ARPA to handle space program. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The first clarification to emerge from the nation's amorphous space policies was revealed on 15 November 1957 when Secretary of Defense McElroy told a press conference he was thinking of centralizing control of space research and development in a special agency, This was the first public announcement of the future birth of ARPA, as it was later called-the Advanced Research Projects Agency. Confirmation of this intent was stated in the President's State -of-the -Union message to Congress on 9 January 1958, when he said that Secretary McElroy "has already decided to concentrate into one organization all the anti-missile and satellite technology undertaken within the Department of Defense. " (History, HqARDC, 1 Jan 31 Dec 1958, Vol 1,prep by ARDC Hist Div, p.7.)

1958 January 13 - .

- The Air Force Ballistic Missile Division continued to study anticipated man-in-space problems. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Chief problems were safe re-entry and recovery of a manned space capsule. Deceleration through re-entry might well exceed the. limits of human tolerance. Experimental evidence, however, suggested that forces high as 18 g's might be tolerated for short periods and that an actual series of tests conducted in Berlin had human subjects enduring 15 g's as long as two minutes without harmful effects., The effect of weightlessness was far more difficult to assess and nearly impossible to simulate for any appreciable length of time other than through actual orbital experimentation. The weight of evidence suggested that manned entry into space and return to earth would be a difficult, but far from impossible, task and the scientific and engineering arts could control the space environment within limits of human tolerance. (Memo, Col L. D. Ely, to Col C. H. Terhune, 13 Jan 58, subj: Additional Human Factors Information.)

1958 January 16 - .

- Aeronutronic concept of an Air Force astronautics program. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Lunex.

Representatives of Aeronutronic Systems, Inc. , visited the ballistic missile division to present their concept of an Air Force astronautics program. Their program was based on use of existing hardware and conservative evaluation of new equipment. to be obtained through technical evolution. Test flight of earth satellites and lunar vehicles would acquire necessary data concerning the space environment. Specific goals included biomedical experiments, development of precision orbital flight, recovery and reconnaissance systems, and lunar impact. From this background of successful technical achievement the program would move to manned satellite flights, lunar flights and manned space exploration. This program was designed to lead to manned flight in approximately four to six years. (Memo, Col L., D. Ely, to Col C. H. Terhune, 23'Jan 59, subj: Astronautics Briefing by Aeronutronic Systems, Inc.)

1958 January 16 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- First draft plan for USAF space weapons. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The first rough draft of a development plan for the Air Force space weapons development and technology program was completed by the ballistic missile division. This was oriented to meet five basic requirements: reconnaissance, communications, manned space flight, technical development and experimental support. To accomplish these objectives it was necessary to make maximum use of Air Force missile hardware and pursue a "daring and bold merger of the aeronautics and manned aircraft experience of the last decade with the rocket and ballistic missile experience in recent years." The program' s fiscal 1958 funding needs were estimated to be as follows: astronautics, $16 million; additional Thor hardware and launch complex for the advanced astronautics program, $10 million. (Memo,. Col C. H. Terhune, Dep Cmdr, Weapon Sys, AFBMD, to Cmdr ARDC, 16 Jan 58, subj: AF Astronautics Development Program.)

1958 January 22 - .

- Command concept of the ARDC missile division's space mission. - .

Related Persons: Schriever.

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Lt General S. E. Anderson, Commander, Air Research and Development Command. outlined the command concept of the missile division's space mission. This was in reply to General Schriever's proposals of 18 December 1957. Said Anderson: "It is our intention to make maximum use of the peculiar talents of your Division while at the same time bringing capabilities of all elements of the Command to bear upon the problems in this area. " Therefore it was the view of the commander that the division should concentrate on ". .,. the development and model improvements. of certain scheduled space systems to include both planning and management associated therewith.: " In application this policy meant that the division would in "certain instances perform technical developments in astronautics.," The Deputy Commander for Research and Development at Command Headquarters was to retain over-all responsibility for formulation of the Astronautics Technical Development Program. (Ltr, Anderson to Schriever, ZZ Jan 58, subj: Proposal for Future Air Force Ballistic Missile and Space Technology Development.)

1958 January 24 - .

- Five year plan for an Air Force Astronautics Program. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Mercury,

Lunex,

Project 7969.

The Air Research and Development Command convened a committee to prepare a final planning draft of an Air Force Astronautics Program for presentation to Mr. W. M. Holaday. The Air Force proposed five year space program included development of research and test vehicles, satellite reconnaissance systems, a lunar based intelligence system, defense systems, logistic requirements of lunar transport, and strategic communications. If the program wei.accepted in its entirety, $1.156 billion in initial funding would be needed in fiscal 1959. (Memo, Col L. D. Ely, Dir Tech Div, to Col C. H. Terhune, AFBMD, 28 Jan 58, subj: Trip Report.) The Air Force invited the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to participate in "a research vehicle program to explore and solve the problems of manned space flight. " Specifically, the Air Force objective was to achieve the earliest possible manned orbital flight which would significantly contribute to development of "follow-on scientific and military space systems." An immediate decision was therefore necessary to determine the best approach to the design of an orbiting research vehicle--should it be a glide vehicle or one designed only to accomplish the satellite mission? Inasmuch as both NACA and the Air Force were well along in their investigations of the best approach to be taken in the design of a manned orbiting research vehicle it was suggested that, "These efforts should be joined at once and brought promptly to a conclusion. " Accordingly NACA was invited to collaborate with Air Research and Development Command on an over-all evaluation of relevant space plans and projects and any program resulting from the joint evaluation would be, it was suggested, "managed and funded along the lines of the X-15 effort. " Specific guide lines were furnished the Advisory Committee to facilitate its response to the Air Force request. (Ltr, Lt Gen D. L. Putt, DCS/D, Hq USAF, to Dr. H. L. Dryden, Dir NACA, 31 Jan 58, no subject.)

1958 January 31 - .

- Wright Air Development Center to find the quickest way to put a man in space. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Air Research and Development Command headquarters directed the Wright Air Development Center to "investigate and evaluate" the quickest way to put a man in space and recover him. Since the crux of the problem was the obvious lack of large high performance booster, the center requested the assistance of the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division in finding a solution to the problem., (Chronological Space History, 1958, prep by AFBMD.)

1958 January 31 - .

- Expedited man-in-space projects. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Mercury,

Dynasoar,

Project 7969.

Air Force headquarters instructed the Air Research and Development Command to expedite man-in-space projects. Air Force headquarters instructed the Air Research and Development Command, in collaboration with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics to " expedite the evaluation of existing or planned projects, appropriate available proposals and other competitive proposals with a view to providing an experimental system capable of an early flight of a manned vehicle making an orbit of the earth." Furthermore, it was asserted that it was "vital to the prestige of the nation that such a feat be accomplished at the earliest technically practicable date--if at all possible before the Russians. " It was therefore important that the evaluation determine whether the objective of a manned space flight could be accomplished more readily under the Dyna Soar program or by means of an orbiting satellite. The minimum time to the first orbital flight and the associated costs were to be determined. The approach to this objective was also to furnish tangible contributions to the over-all Air Force astronautics program. Furthermore, the hazard accompanying such a flight was to be the minimum dictated by sound engineering and experimental flight safety practices. If at all possible, pilot safety was to be secured by furnishing an emergency escape system. (Ltr, Lt Gen D. L. Putt, DCS/D, Hq USAF, to Cmdr, ARDG, 31 Jan 58, subj: Advanced Hypersonic Research Aircraft.)

1958 February 1 - .

- NACA informs the Air Force that it was working on a manned space capsule. - . Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest, Mercury, Project 7969. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics informed the Air Force that it was working on the design of a space capsule and would coordinate on the Air Force space program late in March..

1958 February 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF to use Thor to boost spysats and moon missions by the end of the year. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Secretary of the Air Force James H. Douglas urged the Secretary of Defense to approve Air Force use of Thor missiles to boost test satellites into orbit before the close of the calendar year. The Secretary of Defense was also advised that in the face of the impending establishment of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), the Air Force continue managing development of military space reconnaissance projects, first under the general direction of the Director of Guided Missiles and then under the general direction of ARPA. (Memo, SAF J. H. Douglas, to SOD, 1 Feb 58, subj: Reconnaissance Satellite.) Experimental preliminary steps to a manned space program were directed by Air Force headquarters. development command was assigned authority to develop a recoverable satellite and the first launch date was set for October 1958. The command was also instructed to conduct a moon impact program although the authority to conduct such a program had not yet been granted. Necessary planning action would be taken in order to expedite the program immediately upon approval from the Department of Defense. " (Ltr, Brig Gen H. A. Boushey, DCS/D, Hq USAF, to Cmdr ARDC, 3 Feb 58, subj: Astronautics Program.)

1958 February 7 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- Advanced Research Projects Agency established. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The Department of Defense established the Advanced Research Projects Agency. ARPA was to direct and conduct space research leading toward operational systems. In pursuit of these objectives the agency was authorized management of projects which would be conducted by military departments and it was also empowered to contract directly with individuals, private business organizations, scientific institutions and public agencies. (DOD Dir 5105.15, 7 Feb 58, subj: Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.)

1958 February 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- Blue Scout, Thor to be used for re-entry tests, recoverable satellites, and moon impact probes. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Air Research and Development Command headquarters forwarded further instructions to the missile division as a guide to planning for a space program. The research command was to proceed, when Department of Defense approval was obtained, with development of a ballistic research and test system (WS 609A, later called Blue Scout), specifically designed to satisfy most research flight test requirements. In addition, the Thor missile was to be used as a booster for (1) "Able" re-entry tests; (2) recoverable satellites; (3) and moon impact. The latter program was not yet finally approved but planning actions were authorized to "expedite this project immediately upon receipt of DOD approval" and $1 million had been set aside to cover initial project costs. (Msg, RDX-2-I-E, Hq ARDC to AFBMD, 10 Feb 58.)

1958 February 11 - . LV Family: Thor, Atlas, Titan, Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Thor Able, Thor Agena A.

- 14 Thor boosters to be used during year for space and ICBM missions. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The ballistic missile division informed command headquarters that as many as 14 Thor boosters would be available during the calendar year for special purpose flights. These were tentatively allocated as follows: three were assigned to Phase I "Able" series flights, six were assigned to the program for recoverable satellites, and five were assigned to Phase II "Able" for continued development leading to a Thor ICBM capability. (For a time Thor plus a second stage and warhead was considered as a means of acquiring an early emergency ICBM inventory well ahead of Atlas and Titan.) However, only eight additional launchings could be scheduled through 1958--three for Phase I "Able", three for recoverable satellites to be launched one a month beginning in October, and two in support of Phase II "Able" precisely guided reentry vehicles. Thus this appeared to be the maximum effort possible in the category of space related experimental flights essential to a more advance program. If a greater effort was desirable it would be necessary to obtain additional launching facilities, a problem that might be quickly and easily solved by modifying Navaho launch stands to accept Thor vehicles. (Msg, WDT 2-7E, AFBMD to ARDC, 11 Feb 58.)

1958 February 14 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF to use Thor for variety of space missions. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

KH-1.

The Secretary of the Air Force forwarded to the Secretary of Defense, recommendations on space priorities. These recommendations "should be undertaken promptly by the Air Force. " Other than the first project, converting Thor into an intercontinental range weapon by adding a second stage, the recommendations concerned the following space proposals: (1) develop and orbit a satellite equipped with a small television transmitter to furnish weather information. A Thor plus a second stage could accomplish the first orbital launch by September 1958.: (2) Develop a recoverable satellite equipped to carry a variety of payloads which might be ejected from orbit by decelerating devices. This project would also use a Thor booster with an added Vanguard second stage which could be launched by July 1958. (3) A Thor-Hustler (later called Agena) second stage to launch a 300 pound scientific satellite by October 1958., (4) As previously recommended, the Air Force was prepared to launch a moon rocket by using a Thor plus two Vanguard upper stages. Said the secretary: "In addition to the scientific data that can be obtained from such a flight, the United States could make a major international psychological gain by beating the Russians to the moon. I urge that this Air Force approach be used. " (Memo, SAF J. H. Douglas to the SOD, 14 Feb 58, subj: Thor and WS 117L Program.)

1958 February 24 - .

- USAF design of a life support system for manned spacecraft. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Wright Air Development Center and Air Force Missile Development Center recommended industrial sources and provided the money to study and design a life support system for manned spacecraft. WADC issued a purchase request valued at $445,954 for procurement of the study.

1958 February 26 - .

- USAF to launch a satellite and moon impact probe at the earliest possible date. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

KH-1.

Air Force headquarters affirmed its strong support to demonstrate at the earliest possible date a capability to launch a satellite and to follow as soon thereafter as practicable with a moon impact. "Until such time as the Department of Defense approved early satellite launchings in support of 117L, and launch of a moon impact payload, the research command was directed to "take all actions necessary to be in position to accomplish both projects at the earliest time feasible." The command was further advised to design the first satellite as simply as possible and consider it a "warm up for subsequent more sophisticated vehicles. " Simplicity and an early launch date were considered more important than demonstrating a capability to recover payloads or otherwise demonstrate an advanced state of competence.. (Msg, AFCVC 56978, Hq USAF to ARDC, 26 Feb 58.)

1958 February 28 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF to be responsible for manned space flight. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

Advanced Research Projects Director, Mr. R. W. Johnson declared the Air Force had a ". . . long term development responsibility for manned space flight capability". In pursuit of this objective the Air For ce was told to develop a Thor booster with a suitable second stage vehicle "as an available device for experimental flights with laboratory animals." Provision for the recovery of the orbiting animals in "furtherance of the objective of manned flight" was also authorized. (Memo, R. W. Johnson, Dir, ARPA, to SAF, 28 Feb 58, subj: Reconnaissance Satellites and Manned Space Exploration.)

1958 March 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- WS 117L acceleration approved using Thor boosters. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

KH-1.

The Secretary of Defense approved acceleration of the 117L military satellite system, including test vehicles launched with the Thor booster--a series of orbital experiments that were also considered. The ballistic missile division was instructed to submit a complete development plan and fiscal estimate by 15 March 1958 for "review and approval."

1958 March 4 - .

- Space projects to use same procedures as IRBM/ICBM programs. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

The Air Force Chief of Staff directed that space projects which depended on the use of ballistic missile components use the same procedures as IRBM/ICBM programs. The Air Force Chief of Staff directed that space projects which depended on the use of ballistic missile components "if... will be administered in the same manner and by the same procedures as the ICBM/IRBM programs. " The decision process would be identical and, as in the "ballistic missile programs,approved development plans will constitute action documents. " (Memo, Maj Gen J. E. Smart, AF Asst Vice Chief of Staff, to Air Staff distribution, 4 Mar 58, subj: Space Projects Involving ICBM/IRBM Components.)

1958 March 5 - . LV Family: Thor, Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Thor Agena A, Atlas Agena A.

- USAF lead role in space reaffirmed. WS 117L to be prioritized. - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

KH-1,

WS-117.

The Office of the Secretary of Defense, in the first significant forward step to accelerate development of a space capability, reiterated the space role of the Air Force. In addition to its missile programs the Air Force was responsible for the 117L system and "... has a recognized long term development responsibility for manned space flight capability with the primary objective of accomplishing satellite flight as soon as technology permits." Furthermore, the Air Force was told it was to carry forward and accelerate the Atlas 117L project "under the highest national priority in order to attain an initial operational capability in the earliest possible date," But the proposed interim system using a Thor booster combined with a second stage and recoverable capsule "should not be pursued. " The Department of Defense did agree that a Thor booster with a suitable second stage "may be the most promptly and readily available device for experimental flights with laboratory animals" and development of such hardware including a system for recovery of animals was authorized. (Msg 03-014, Cmdr ARDC, to Cmdr AFBMD, 5 Mar 58.)

1958 March 8 - .

- USAF Objective: "Manned Space Flight to the Moon and Return" - .

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest,

Lunex.

The Air Force Ballistic Missile Division proposed an over-all space objective about which all other experimental projects would be oriented. This goal was briefly stated as "Manned Space Flight to the Moon and Return. " To achieve this ultimate accomplishment many other space projects and programs would be necessary. The final goal would furnish an objective and a means to develop an integrated space program instead of isolated space ventures whose value might be unrelated to any national purpose. Admittedly, achieving this goal would require much preliminary work and completion of the following programs: Instrumented Satellite Flights and Return; Animals in Satellite Orbit and Return; Biomedical Experiments in Satellite Flights; Man in Satellite Orbit and Return; Instruments and Equipment Around Moon and Return; Animal Around Moon and Return; Instrumented Hard Landing on Moon; Instruments -Equipment Soft Landing on Moon and Return; Animal Soft Landing on Moon and Return; Man Around Moon and Return; Manned Landing on the Moon and Return (Memo, Col L. D. Ely, to Co) C. H. Terhune, 8 Mar 58, subj: Meeting with Hq ARDC Biomedical and Behavioral Sciences Panels, 10-12 Mar.)

1958 March 10 - .

- MISS Working Conference - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Caldwell,

Schriever.

Spacecraft: Mercury,

Project 7969,

Man-In-Space-Soonest.

A working conference in support of the Air Force 'Man-in-Space Soonest' (MISS) was held at the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division in Los Angeles, California. General Bernard Schriever, opening the conference, stated that events were moving faster than expected. By this statement he meant that Roy Johnson, the new head of the Advanced Research Projects Agency, had asked the Air Force to report to him on its approach to putting a man in space soonest. Johnson indicated that the Air Force would be assigned the task, and the purpose of the conference was to produce a rough-draft proposal. At that time the Air Force concept consisted of three stages: a high-drag, no-lift, blunt-shaped spacecraft to get man in space soonest, with landing to be accomplished by a parachute; a more sophisticated approach by possibly employing a lifting vehicle or one with a modified drag; and a long-range program that might end in a space station or a trip to the moon.

1958 March 12 - . Launch Vehicle: Thor.

- USAF accelerated development plan for the man in space program. - .

Related Persons: Schriever.

Spacecraft: Man-In-Space-Soonest.

An Air Research and Development Command meeting held at the ballistic missile division to prepare an abbreviated development plan for the man in space program. The general Air Research and Development Command headquarters outline of the immediate planning task centered about designing a manned vehicle within a weight limitation of 2, 700-3,000 pounds which would have to contain a man, a life support system with a capacity to remain aloft for 48 hours, telemetry-communications, and a recovery system. The Air Force Ballistic Missile Division approach was directed to a more distant goal, "Man on the Moon and Return. " By the second day of the conference general agreement on program objectives had been reached. Technical recommendations included selection of an improved thrust Thor with a fluorine-hydrazine second stage, 2, 700-3, 000 pound spacecraft and a General Electric guidance system. As then planned the complete experimental and test program would require approximately 30 Thor boosters, 8 to 12 Vanguard second stages and about 20 fluorine-hydrazine second stages for testing and advanced phases of the program. By the third day an abbreviated dra.ft development plan had been completed. The conference was pervaded by a strong sense of urgency, motivated by the dramatic Air Force mission to get a man in space at the earliest possible time. Those attending the conference anticipated accelerated program approval and scheduled contractor selection to begin on or about 10 April 1958., (Memo, Col C. H. Terhune, Dep Cmdr, Tech Operations, to Maj Gen B. A. Schriever, Cmdr, AFBMD, 25 Mar 58, subj: Man in Space Meeting at AFBMD, lu-12 March 58.)

1958 March 14 - .