Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Saturn V

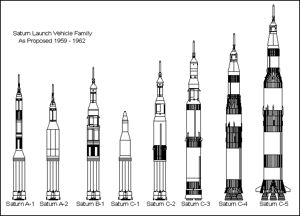

Saturn V Geneology

Credit: © Mark Wade

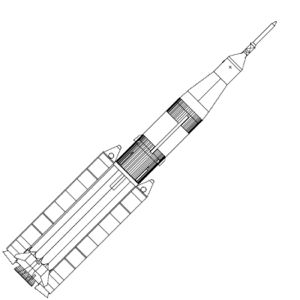

AKA: SaturnV. Status: Retired 1973. First Launch: 1967-11-09. Last Launch: 1973-05-14. Number: 13 . Payload: 118,000 kg (260,000 lb). Thrust: 33,737.90 kN (7,584,582 lbf). Gross mass: 3,038,500 kg (6,698,700 lb). Height: 102.00 m (334.00 ft). Diameter: 10.06 m (33.00 ft). Apogee: 185 km (114 mi).

The Saturn launch vehicle was the penultimate expression of the Peenemuende Rocket Team's designs for manned exploration of the moon and Mars. The designs were continuously developed and improved, starting from the World War II A11 and A12 satellite and manned shuttle launcher, through the designs made public in the Collier's Magazine series of the early 1950's, until the shock of the first Sputnik launch brought sudden real interest from the U.S. government. On December 30 1957 Von Braun produced a 'Proposal for a National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Plan'. This had the first mention of a 1,500,000 lbf booster (Juno V, later Saturn I). By July of the following year Huntsville had in hand the contract from ARPA to proceed with design of the Juno V.

Following transfer of the Peenemuende Rocket Team from the US Army to NASA, a year after the first plan was mooted, Von Braun briefed NASA on plans for booster development at Huntsville with objective of manned lunar landing. It was initially proposed that 15 Juno V (Saturn I) boosters assemble a 200,000 kg payload in earth orbit for direct landing on moon. NASA produced two months later, on February 15, 1959, its plan for development in the next decade of Vega (later cancelled after NASA discovered the USAF was secretly developing the similar Hustler (Agena) upper stage), Centaur, Saturn, and Nova launch vehicles (Juno V renamed Saturn I at this point). Throughout the initial planning, Presidential decision, and landing mode debate for the Apollo lunar landing goal, a variety of Saturn and Nova configurations were considered. Of these, only the C-1 and C-5 were taken through to further development.

| Configuration | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | LEO Payload - kg | Escape Payload - kg |

| Saturn A-1 | 8 x H-1 | 2 x LR89 | 2 x LR115 | |||

| Saturn A-2 | 8 x H-1 | 4 x S-3 | 2 x LR115 | |||

| Saturn B-1 | 8 x H-1 | 4 x LR89 | 5 x LR115 | 2 x LR115 | ||

| Saturn C-1 | 8 x H-1 | 6 x LR115 | 2 x LR115 | 9,000 | 2,200 | |

| Saturn C-2 | 8 x H-1 | 1 x J-2 | 6 x LR115 | 2 x LR115 | 20,000 | 6,800 |

| Saturn C-3 | 2 x F-1 | 4 x J-2 | 6 x LR115 | 2 x LR115 | ||

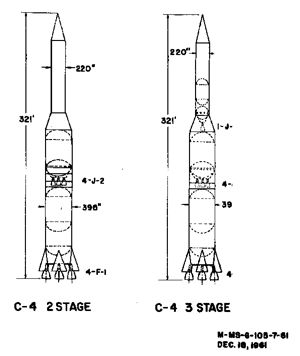

| Saturn C-4 | 4 x F-1 | 4 x J-2 | 1 x J-2 | |||

| Saturn C-5 | 5 x F-1 | 5 x J-2 | 1 x J-2 | 127,000 | 45,000 | |

| Nova Basic | 6 x F-1 | 1 x F-1 | 4 x J-2 | 68,000 | 16,000 | |

| Nova A | 4 x F-1 | 4 x J-2 | 5 x LR115 | 1 x 2700 kgf | 68,000 | 27,000 |

| Nova B | 6 x F-1 | 8 x J-2 | 7 x LR115 | 1 x LR115 | 112,000 | 47,000 |

| Nova C | 6 x F-1 | 8 x J-2 | 1 x Nerva | 68,000 | 38,000 | |

| Nova D | 6 x F-1 | 8 x J-2 | 1 x Nerva | 112,000 | 65,000 | |

| Nova N-F1 | 8 x F-1 | 4 x F-1 | 1 x J-2 | 70,000 | ||

| Nova N-M1 | 8 x F-1 | 4 x M-1 | 1 x J-2 | 180,000 | 90,000 |

After the Saturn V drawings had been issued, Marshall engineers immediately turned to considering further developments of the basic launch vehicle. These would be required for Apollo Applications, Manned Orbiting Research Laboratory, Mars fly-by, and Mars landing missions in the 1970's and 1980's.

Contracts were let for a variety of trade studies. There were limits to how far the core stack could be stretched, dictated by the 410 foot maximum overhead crane height in the Vertical Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center (this did not prevent 470 foot versions being proposed, including the nuclear NERVA third stage, for manned missions to Mars - they'd just have to raise the roof, darn it). Given these limits, a variety of strap-on solid motors were considered.

The most feasible, lowest development cost improvement would have used upgraded F-1 motors, an S- IC first stage stretch, modest upgrades to the J-2 upper stage motors, and proven 120 inch solid rocket motor strap-ons. If a follow-on Saturn V production contract had ever been issued, it probably would have been for this configuration. More advanced versions would have used Flox oxidizer (liquid fluorine mixed with the liquid oxygen oxidizer - nasty to handle, but increased performance with minimal changes to the existing motors and pumps), new technology engines (plug nozzles or high-pressure combustion engines - the ancestors of the Shuttle SSME's). Instead America abandoned its heavy lift capability and further manned exploration of space. The two unused flightworthy Saturn V's from the initial production run of 15 became tourist displays at Cape Canaveral and Huntsville. A third Saturn V, exhibited in Houston, is made up of static test article stages.

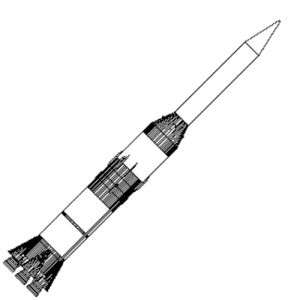

Saturn II First Stage Derivatives

There was a large payload gap between the Saturn IB's 19,000 kg low-earth orbit capacity and the two-stage Saturn V's 100,000 kg capability. Marshall considered the best way to fill the gap was to use the Saturn V's second stage, the S-II, as the first stage of an intermediate launch vehicle.

Using the S-II had several advantages. It could be mounted atop a 'milk stool' and use the existing Saturn V launch gantry arms and plumbing for fueling and preparations (this approach was actually used later for Saturn IB launches for Skylab and ASTP). Discontinuing use of the Saturn IB would eliminate one rocket stage production line together with associated configuration and quality control headaches.

A dazzling array of combinations of S-II stages, S-IVB stages, and a variety of solid rocket motor strapons were considered. In most cases the S-II would have to be fitted with 'sea-level' versions of its J-2 engines, which were designed only for operation in near-vacuum conditions. This resulted in a decrease in engine performance. Since the S-II stage did not have enough thrust to get off the ground by itself, various combinations of solid rocket motor augmentation and propellant off-loads had to be used. The resulting configurations would have provided a payload range of between 13,000 kg and 66,000 kg to low earth orbit, thereby filling the payload gap and replacing the S-IB.

LEO Payload: 118,000 kg (260,000 lb) to a 185 km orbit at 28.00 degrees. Payload: 47,000 kg (103,000 lb) to a translunar trajectory. Development Cost $: 7,439.600 million. Launch Price $: 431.000 million in 1967 dollars in 1966 dollars.

Stage Data - Saturn V

- Stage 1. 1 x Saturn IC. Gross Mass: 2,286,217 kg (5,040,245 lb). Empty Mass: 135,218 kg (298,104 lb). Thrust (vac): 38,703.160 kN (8,700,816 lbf). Isp: 304 sec. Burn time: 161 sec. Isp(sl): 265 sec. Diameter: 10.06 m (33.00 ft). Span: 19.00 m (62.00 ft). Length: 42.06 m (137.99 ft). Propellants: Lox/Kerosene. No Engines: 5. Engine: F-1. Status: Out of Production.

- Stage 2. 1 x Saturn II. Gross Mass: 490,778 kg (1,081,980 lb). Empty Mass: 39,048 kg (86,086 lb). Thrust (vac): 5,165.790 kN (1,161,316 lbf). Isp: 421 sec. Burn time: 390 sec. Isp(sl): 200 sec. Diameter: 10.06 m (33.00 ft). Span: 10.06 m (33.00 ft). Length: 24.84 m (81.49 ft). Propellants: Lox/LH2. No Engines: 5. Engine: J-2. Status: Out of Production.

- Stage 3. 1 x Saturn IVB (S-V). Gross Mass: 119,900 kg (264,300 lb). Empty Mass: 13,300 kg (29,300 lb). Thrust (vac): 1,031.600 kN (231,913 lbf). Isp: 421 sec. Burn time: 475 sec. Isp(sl): 200 sec. Diameter: 6.61 m (21.68 ft). Span: 6.61 m (21.68 ft). Length: 17.80 m (58.30 ft). Propellants: Lox/LH2. No Engines: 1. Engine: J-2. Status: Out of Production. Comments: Saturn V version of S-IVB stage.

More at: Saturn V.

| Jarvis launch vehicle American orbital launch vehicle. Launch vehicle planned for Pacific launch based on Saturn V engines, tooling. Masses, payload estimated. |

| Saturn C-3 The launch vehicle concept considered for a time as the leading contender for the Earth Orbit Rendezvous approach to an American lunar landing. |

| Saturn C-3B American orbital launch vehicle. Final configuration of the Saturn C-3 at the time of selection of the Saturn C-5 configuration for the Apollo program in December 1961. |

| Saturn C-3BN American nuclear orbital launch vehicle. Version of Saturn C-3 considered with small nuclear thermal stage in place of S-IVB oxygen/hydrogen stage. |

| Saturn C-4 American orbital launch vehicle. The launch vehicle actually planned for the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous approach to lunar landing. The Saturn C-5 was selected instead to have reserve capacity. |

| Saturn C-4B American orbital launch vehicle. Final configuration of the Saturn C-4 at the time of selection of the Saturn C-5 configuration for the Apollo program in December 1961. Only Saturn configuration with common bulkhead propellant tanks in first stage, resulting in shorter vehicle than less powerful Saturn C-3. |

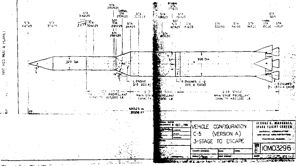

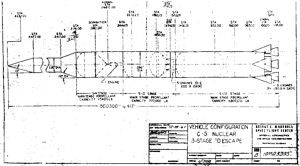

| Saturn C-5 American orbital launch vehicle. Final configuration of Saturn C-5 at the time of selection of this configuration for the Apollo program in December 1961. The actual Saturn V would be derived from this, but with an increased-diameter third stage (6.61 m vs 5.59 m in C-5) and increased propellant load in S-II second stage. |

| Saturn C-5N American nuclear orbital launch vehicle. Version of Saturn C-5 considered with small nuclear thermal stage in place of S-IVB oxygen/hydrogen stage. |

| Saturn INT-17 North American study, 1966. Saturn variant with a modified S-II first stage with seven high-performance HG-3 engines; S-IVB second stage. Poor performance and cost-effectiveness and not studied further. |

| Saturn INT-18 North American study, 1966. Saturn variant with Titan UA1205 or 1207 motors as boosters, Saturn II stage as core, and Saturn IVB upper stage. Various combinations of numbers of strap-ons, propellant loading of the two core stages, and sea-level versus altitude ignition were studied. |

| Saturn INT-19 North American study, 1966. Saturn variant with 4 to 12 Minuteman motors as boosters, Saturn II stage as core, and Saturn IVB upper stage. Saturn II stage would be fitted with lower expansion ratio engines and would ignite at sea level. Various combinations of numbers of strap-ons, propellant loading of the two core stages were studied. |

| Saturn INT-20 American orbital launch vehicle. Saturn variant consisting of S-IC first stage and S-IVB second stage. Consideration was given to deleting one or more of the F-1 engines in the first stage. |

| Saturn INT-21 American orbital launch vehicle. Saturn variant consisting of S-IC first stage and S-II second stage. This essentially flew once to launch Skylab in 1972, although the IU was located atop the Skylab space station (converted S-IVB stage) rather than atop the S-II as in the INT-21 design. |

| Saturn LCB-Storable-140 American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): Low Cost Booster, Single Pressure-fed N2O4/UDMH Propellant engine, HY-140 Steel Hull. |

| Saturn MLV-V-1 American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Improved Saturn V configuration studied under contract NAS8-11359. Saturn IC stretched 240 inches with 5.6 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1A engines; S-II stretched 41 inches with 1.0 million pounds propellant and 5 J-2 engines; S-IVB strengthened but with standard 230,000 lbs propellant, 1 J-2 engine. |

| Saturn MLV-V-1/J-2T/200K American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Improved Saturn V configuration studied under contract NAS8-11359. Variant of MLV-V-1 with toroidal J-2T-200K engines replacing standard J-2 engines in upper stages. |

| Saturn MLV-V-1/J-2T/250K American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Improved Saturn V configuration studied under contract NAS8-11359. Variant of MLV-V-1 with toroidal J-2T-250K engines replacing standard J-2 engines in upper stages. |

| Saturn MLV-V-1A American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Saturn IC stretched 240 inches with 5.6 million pounds propellant and 6 F-1 engines; S-II stretched 156 inches with 1.2 million pounds propellant and 7 J-2 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 J-2 engine. |

| Saturn MLV-V-2 American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Saturn IC stretched 240 inches with 5.6 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1A engines; S-II stretched 41 inches with 1.0 million pounds propellant and 5 J-2 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 HG-3 engine. |

| Saturn MLV-V-3 American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Ultimate core for improved Saturn V configurations studied under contract NAS8-11359. Saturn IC stretched 240 inches with 5.6 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1A engines; S-II stretched 156 inches with 1.2 million pounds propellant and 5 HG-3 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 HG-3 engine. |

| Saturn MLV-V-4(S) American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. Saturn V core, strengthened but not stretched, with 4 Titan UA1205 strap-on solid rocket boosters. |

| Saturn MLV-V-4(S)-A American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1965. 4 Titan UA1205 solid rocket boosters; Saturn IC stretched 337 inches with 6.0 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1 engines; S-II with 970,000 pounds propellant and 5 J-2 engines; S-IVB strengthened but with standard 230,000 lbs propellant, 1 J-2 engine. |

| Saturn MLV-V-4(S)-B American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1967. Configuration of improved Saturn 5 with Titan UA1207 120 inch solid rocket boosters. Saturn IC stretched 336 inches with 6.0 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1 engines; Saturn II and Saturn IVB stages strengthened but not stretched. Empty mass of stages increased by 13.9% (S-IC), 8.6% (S-II) and 11.8% (S-IVB). Studied again by Boeing in 1967 as Saturn V-4(S)B. |

| Saturn S-IC-TLB American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): S-IC Technology Liquid Booster: 260 inch liquid booster with 2 x F-1 engines, recoverable/reusable |

| Saturn V 2 American orbital launch vehicle. Two stage version of Saturn V, consisting of 1 x Saturn S-IC + 1 x Saturn S-II, used to launch Skylab. |

| Saturn V/4-260 American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1967-1968. Use of full length 260 inch solid rocket boosters with stretched Saturn IC stages presented problems, since the top of the motors came about half way up the liquid oxygen tank of the stage, making transmission of loads from the motors to the core vehicle complex and adding a great deal of weight to the S-IC. Boeing's solution was to retain the standard length Saturn IC, with the 260 inch motors ending half way up the S-IC/S-II interstage, but to provide additional propellant for the S-IC by putting propellant tanks above the 260 inch boosters. These would be drained first and jettisoned with the boosters. This added to the plumbing complexity but solved the loads problem. |

| Saturn V-23(L) American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1967. 4 260 inch liquid propellant boosters (each with 2 F-1's!).; Saturn IC stretched 240 inches with 5.6 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1 engines; S-II strengthened but with standard 930,000 pounds propellant and 5 J-2 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 J-2 engine. |

| Saturn V-24(L) American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1967. 4 260 inch liquid propellant boosters (each with 2 F-1A).; Saturn IC stretched 336 inches with 6.0 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1A engines; S-II stretched 156 inches with 1.2 million pounds propellant and 5 HG-3 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 HG-3 engine. Not studied in detail since vehicle height of 600 feet with payload exceeded study limit of 410 feet. |

| Saturn V-25(S)B American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1967. 4 156 inch solid propellant boosters; Saturn IC stretched 498 inches with 6.64 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1 engines; S-II standard length with 5 J-2 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 J-2 engine. |

| Saturn V-25(S)U American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1968. 4 156 inch solid propellant boosters; Saturn IC stretched 498 inches with 6.64 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1 engines; S-II standard length with 5 J-2 engines. This vehicle would place Nerva nuclear third stage into low earth orbit, where five such stages would be assembled together with the spacecraft for a manned Mars expedition. |

| Saturn V-3B American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1967. Variation on MSFC 1965 study Saturn MLV-V-3 but with toroidal engines. Saturn IC stretched 240 inches with 5.6 million pounds propellant (but only 4.99 million pounds usable without solid rocket boosters) and 5 F-1A engines; S-II stretched 186 inches with 1.29 million lbs propellant and 5 J-2T-400 engines; S-IVB stretched 198 inches with 350,000 lbs propellant, 1 J-2T-400 engine. |

| Saturn V-4X(U) American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing study, 1968. Four core vehicles from Saturn V-25(S) study lashed together to obtain million-pound payload using existing hardware. First stage consisted of 4 Saturn IC's stretched 498 inches with 6.64 million pounds propellant and 5 F-1 engines; second stage 4 Saturn II standard length stages with 5 J-2 engines |

| Saturn V-A American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1968. Essentially identical to Saturn INT-20; standard Saturn IC stage together with Saturn IVB second stage, with Centaur third stage for deep space missions. |

| Saturn V-B American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1968. Intriguing stage-and-a-half to orbit design using Saturn S-ID stage. The S-ID would be the same length and engines as the standard Saturn IC, but the four outer engines and their boost structure would be jettisoned once 70% of the propellant was consumed, as in the Atlas ICBM. This booster engine assembly would be recovered and reused. The center engine would be gimbaled and serve as a sustainer engine to put the rest of the vehicle and its 50,000 pound payload into orbit. At very minimal cost (36 months lead-time and $ 150 million) the United States could have attained a payload capability and level of reusability similar to that of the space shuttle. |

| Saturn V-C American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1968. S-ID stage-and-a-half first stage and Saturn IVB second stage. Centaur available as third stage for deep space missions. 30% performance improvement over Saturn V-A/Saturn INT-20 with standard Saturn IC first stage. |

| Saturn V-Centaur American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1968. S-ID stage-and-a-half first stage and Saturn IVB second stage. Centaur available as third stage for deep space missions. 30% performance improvement over Saturn V-A/Saturn INT-20 with standard Saturn IC first stage. |

| Saturn V-D American orbital launch vehicle. MSFC study, 1968. Rehashed the Boeing 1967 studies, covering a variety of stage stretches and 120, 156, or 260 inch solid rocket boosters, but with S-ID stage-and-a-half first stage. |

| Saturn V-ELV American orbital launch vehicle. NASA study, 1966. No-height-limitation stretched Saturn with Titan UA1207 motors for thrust augmentation. |

| Winged Saturn V North American's study was dated 18 March 1963. The second alternative was a two-stage reusable booster derived from the Saturn V. This would boost either an 11,400 kg cargo, or a half-disc lifting body spaceplane, which would accommodate two crew plus ten passengers and minor cargo |

Family: orbital launch vehicle. People: von Braun. Country: USA. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing, Mercury, Apollo LM, Apollo CSM, Gemini, Gemini Lunar Lander, Lunar Bus, Apollo ULS, Apollo M-1, Apollo W-1, Apollo D-2, Apollo R-3, Apollo L-2C, Apollo Lenticular, LORL, Apollo LM Shelter, Apollo LM Taxi, CSM Electrical, Self-Deploying Space Station, Apollo LM Truck, Apollo MSS, Gemini - Saturn V, Saturn II Stage Wet Workshop, Voyager 1973, GE Lunar NEP Tug, MORL Mars Flyby, Apollo LMSS, Gemini Lunar Surface Rescue Spacecraft, Apollo LTA, Gemini Lunar Surface Survival Shelter, Gemini LORV, Apollo 120 in Telescope, Apollo LMAL, Apollo LASS, LESA Lunar Base, Space Station 1970, Apollo ALSEP, Apollo LRM, LESA Shelter, Space Base, S-IVB Advanced Station, Skylab Lunar Orbit Station, Apollo LRV, PFS, Skylab, AES Lunar Base, ALSS Lunar Base. Projects: Apollo. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral, Cape Canaveral LC39A, Cape Canaveral LC39B. Stages: Saturn IC, Saturn II, Saturn IVB (S-IB). Bibliography: 16, 17, 18, 2, 216, 222, 228, 229, 230, 231, 233, 26, 27, 33, 34, 47, 6, 60, 4832, 8601.

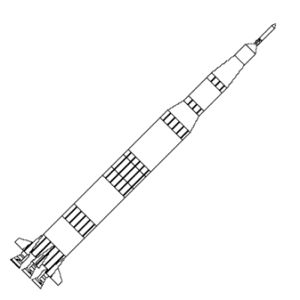

| Saturn V 1 Credit: NASA |

| Saturn V Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn II stage Credit: © Mark Wade |

| J-2 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Launch vehicles Launch vehicles of the world as known in 1980 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| N1 and Saturn V Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn V Credit: NASA |

| Saturn V LV Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn V 2 Credit: NASA |

| Saturn V No. b Credit: NASA |

| Saturn V No. d Credit: NASA |

| Saturn V Title |

| Saturn A-1 to C-5 Credit: © Mark Wade |

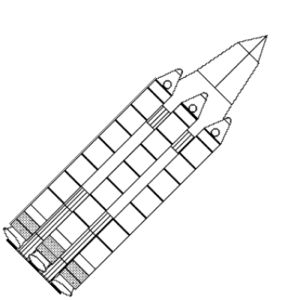

| Saturn C-4B 2 Stage Saturn C-4B 2 Stage version Nov 1961 Credit: © Mark Wade |

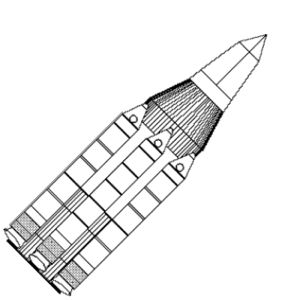

| Saturn C-4B final Saturn C-4B final configuration Nov 1961 Credit: © Mark Wade |

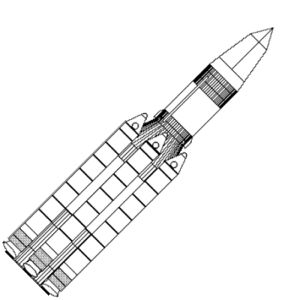

| Saturn 5 final Saturn 5 final configuration Nov 1961 Credit: © Mark Wade |

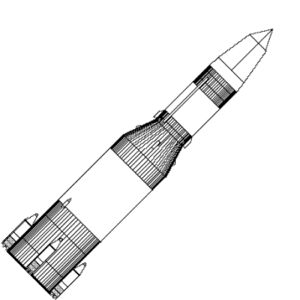

| Saturn 5 nuclear Saturn 5 nuclear configuration Nov 1961 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn MLV 1.37 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 2-120-4 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 2-120-5 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn MLV 2-120-7 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 2 w MM SO Credit: © Mark Wade |

1953 March - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Research on 1 million lb thrust engine begun. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Research on 1-million-pound thrust plus engine begun at Rocketdyne, the feasibility of which was established in March 1955..

1955 March - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Feasibility of million-pound-thrust liquid-fueled rocket engine established - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The feasibility of a million-pound-thrust liquid-fueled rocket engine established by the Rocketdyne Division of North American Aviation, Inc..

1956 January 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First test of 400,000+ lb thrust engine. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. First U.S.-built complete liquid-rocket engine having a thrust in excess of 400,000 pounds was fired for the first time at Santa Susana, Calif..

1956 November 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Million pound thrust test stand activiated. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocket test stand capable of testing engines to 1 million pounds thrust activated at Edwards AFB, which became operational in March 1957..

1958 June 23 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Preliminary design begun on F-1 - 1.5 million pounds thrust rocket engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The U.S. Air Force contracted with NAA, Rocketdyne Division, for preliminary design of a single-chamber, kerosene and liquid-oxygen rocket engine capable of 1 to 1.5 million pounds of thrust. During the last week in July, Rocketdyne was awarded the contract to develop this engine, designated the F-1.

1958 August 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rocketdyne gets F-1 engine contract. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocketdyne Division of North American announced an Air Force contract for a 1-million-pound thrust engine..

1958 November 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- F-1 engine gets highest priority. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA requested DX priority for 1.5-million-pound-thrust F-1 engine project and Project Mercury..

1958 December 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rocketdyne gets contract to develop F-1 engine. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA awarded contract to Rocketdyne of North American to build single-chamber 1.5-million-pound-thrust rocket engine..

1959 January 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- 1 million pound engine demonstrated. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocketdyne demonstrated 1-million-pound-thrust liquid-propellant rocket combustion chamber at full power..

1959 March 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Thrust chamber of the Saturn F-1 engine successfully static-fired - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The thrust chamber of the F-1 engine was successfully static-fired at the Santa Susana Air Force-Rocketdyne Propulsion Laboratory in California. More than one million pounds of thrust were produced, the greatest amount attained to that time in the United States.

1959 June 25-26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Study and research areas for manned flight to and from the moon - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Mercury. Members of the Research Steering Committee determined the study and research areas which would require emphasis for manned flight to and from the moon and for intermediate flight steps:. Additional Details: here....

1959 August 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Static firing of the first Saturn planned for early 1960 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) directed the Army Ordnance Missile Command to proceed with the static firing of the first Saturn vehicle, the test booster SA-T, in early calendar year 1960 in accordance with the $70 million program and not to accelerate for a January 1960 firing. ARPA asked to be informed of the scheduled firing date.

1959 November 27 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Study group to recommend upper-stage configurations - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

While awaiting the formal transfer of the Saturn program, NASA formed a study group to recommend upper-stage configurations. Membership was to include the DOD Director of Defense Research and Engineering and personnel from NASA, Advanced Research Projects Agency, Army Ballistic Missile Agency, and the Air Force. This group was later known both as the Saturn Vehicle Team and the Silverstein Committee (for Abe Silverstein, Chairman).

1959 December 31 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- NASA approval of Saturn development program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Silverstein,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

NASA accepted the recommendations of the Saturn Vehicle Evaluation Committee Silverstein Committee on the Saturn C-1 configuration and on a long-range Saturn program. A research and development plan of ten vehicles was approved. The C-1 configuration would include the S-1 stage (eight H-1 engines clustered, producing 1.5 million pounds of thrust), the S-IV stage (four engines producing 80,000 pounds of thrust), and the S-V stage two engines producing 40,000 pounds of thrust.

1960 January 14 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Super booster program to be accelerated - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Eisenhower,

Glennan,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower directed NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan "to make a study, to be completed at the earliest date practicable, of the possible need for additional funds for the balance of FY 1960 and for FY 1961 to accelerate the super booster program for which your agency recently was given technical and management responsibility."

1960 February 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Lunar Program Based on Saturn Systems - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing. Study issued by Huntsville of lunar landing alternatives using Saturn systems. Huntsville transferred from Army to NASA. Vought study on modular approach to lunar landing. Internally NASA decides on lunar landing as next objective after Mercury..

1960 Summer - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Boilerplate Apollo spacecraft to be used on Saturn C-1 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

H. Kurt Strass of STG and John H. Disher of NASA Headquarters proposed that boilerplate Apollo spacecraft be used in some of the forthcoming Saturn C-1 hunches. (Boilerplates are research and development vehicles which simulate production spacecraft in size, shape, structure, mass, and center of gravity.) These flight tests would provide needed experience with Apollo systems and utilize the Saturn boosters effectively. Four or five such tests were projected. On October 5, agreement was reached between members of Marshall Space Flight Center and STG on tentative Saturn vehicle assignments and flight plans.

1960 September 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contract for development of the Saturn J-2 engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. A NASA contract for approximately $44 million was signed by Rocketdyne Division of NAA for the development of the J-2 engine..

1960 October 5 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Discussion of Saturn and Apollo guidance integration - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Members of STG visited the Marshall Space Flight Center to discuss possible Saturn and Apollo guidance integration and potential utilization of Apollo onboard propulsion to provide a reserve capability. Agreement was reached on tentative Saturn vehicle assignments on abort study and lunar entry simulation; on the use of the Saturn guidance system; and on future preparations of tentative flight plans for Saturns SA-6, 8, 9, and 10.

1961 February 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First static test of prototype F-1 thrust chamber - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocketdyne Division's first static test of a prototype thrust chamber for the F-1 engine achieved a thrust of 1.550 million pounds in a few seconds at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif..

1961 April 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- 1,640 million pounds of thrust achieved in static- firing of the F-1 engine - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. The Marshall Space Flight Center announced that 1.640 million pounds of thrust was achieved in a static- firing of the F-1 engine thrust chamber at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. This was a record thrust for a single chamber..

1961 April 12 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Seamans established the permanent Saturn Program Requirements Committee - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., established the permanent Saturn Program Requirements Committee. Members were William A. Fleming, Chairman; John L. Sloop, Deputy Chairman; Richard B. Canright; John H. Disher; Eldon W. Hall; A. M. Mayo; and Addison M. Rothrock, all of NASA Headquarters. The Committee would review on a continuing basis the mission planning for the utilization of the Saturn and correlate such planning with the Saturn development and procurement plans.

1961 May - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Reevaluation of the Saturn C-2 to support circumlunar missions - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. The Marshall Space Flight Center began reevaluation of the Saturn C-2 configuration capability to support circumlunar missions. Results showed that a Saturn vehicle of even greater performance would be desirable..

1961 June 20 - . LV Family: Saturn V. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-3.

- Donald Heaton had been appointed Chairman of an Ad Hoc Task Group - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Robert C. Seamans, Jr., NASA Associate Administrator, notified the Directors of Launch Vehicle Program, Space Flight Programs, Advanced Research Programs, and Life Sciences Programs that Donald H. Heaton had been appointed Chairman of an Ad Hoc Task Group. It would establish program plans and supporting resources necessary to accomplish the manned lunar landing mission by the use of rendezvous techniques, using the Saturn C-3 launch vehicle, with a target date of 1967. Guidelines and operating methods were similar to those of the Fleming Committee. Members of the Task Group would be appointed from the Offices of Launch Vehicle Programs, Space Flight Program, Advanced Research Programs, and Life Sciences Programs. The work of the Group (Heaton Committee) would be reviewed weekly. The study was completed during August.

1961 July 7 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- NASA and DoD to study development of large launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The NASA Administrator and the Secretary of Defense concluded an agreement to study development of large launch vehicles for the national space program. For this purpose, the DOD-NASA Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group was created, reporting to the Associate Administrator of NASA and to the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Deputy Director of Defense Research and Engineering).

1961 July 11 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- F-1 engine begins static testing. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. NASA announced that a complete F-1 engine had begun a series of static test firings at Edwards Rocket Test Center, Calif..

1961 July 20 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group, established on July 7, 1961, began its formal existence with seven DOD and seven NASA members and alternates.. Additional Details: here....

1961 August 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo launch site study begun. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA headquarters announced that it was making a world-wide study of possible launching sites for Moon vehicles; the size, power, noise, and possible hazards of Saturn-Nova type rockets requiring greater isolation for public safety than presently available.

1961 August 16 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First F-1 firing. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. F-1 rocket engine tested in first of firing series of the complete flight system..

1961 August 23 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Golovin Committee evaluates three rendezvous methods for manned lunar landing - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM ECS,

LM Source Selection.

The Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group (Golovin Committee) notified the Marshal! Space Flight Center (MSFC), Langley Research Center, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that the Group was planning to undertake a comparative evaluation of three types of rendezvous operations and direct flight for manned lunar landing. Rendezvous methods were earth orbit, lunar orbit, and lunar surface. MSFC was requested to study earth orbit rendezvous, Langley to study lunar orbit rendezvous, and JPL to study lunar surface rendezvous. The NASA Office of Launch Vehicle Programs would provide similar information on direct ascent. Additional Details: here....

1961 August 31 - . LV Family: Saturn V. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-3.

- Chamberlain proposes lunar landing by Gemini - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Gemini. Landing by Gemini using 4,000 kg wet/680 kg empty lander and Saturn C-3 booster. Landing by January 1966..

1961 September 5 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Purchase of land for Saturn V launch facilities. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Authorization for NASA to acquire necessary land for additional launch facilities at Cape Canaveral was approved by the Senate..

1961 September 11 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- North American selected to build S-II stage. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

NASA selected NAA to develop the second stage (S-II) for the advanced Saturn launch vehicle. The cost, including development of at least ten vehicles, would total about $140 million. The S-II configuration provided for four J-2 liquid-oxygen - liquid-hydrogen engines, each delivering 200,000 pounds of thrust.

1961 September 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- 36 companies invited to bid on the first stage of advanced Saturn - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA invited 36 companies to bid on a contract to produce the first stage of the advanced Saturn launch vehicle. Representatives of interested companies would attend a pre-proposal conference in New Orleans, La., on September 26. Bids were to be submitted by October 16 and NASA would then select the contractor, probably in November.

1961 September 25 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- S-IC fabrication plant manager named. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Dr. George N. Constan of Marshall Space Flight Center named as acting manager of the new NASA Saturn fabrication plant near New Orleans by Director von Braun of Marshall Space Flight Center..

1961 September 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Bidders conference for S-IC stage. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing. NASA bidders conference on a contract to produce the booster (S-I) stage of the Saturn vehicle was held at the Municipal Auditorium, New Orleans..

1961 October 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- S- IVB stage to have a single J-2 engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The MSFC-STG Space Vehicle Board at NASA Headquarters discussed the S- IVB stage, which would be modified by the Douglas Aircraft Company to replace the six LR-115 engines with a single J-2 engine. Funds of $500,000 were allocated for this study to be completed in March 1962. Additional Details: here....

1961 November 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Saturn S-II to use five J-2 engines - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Marshall Space Flight Center directed NAA to redesign the advanced Saturn second stage (S-II) to incorporate five rather than four J-2 engines, to provide a million pounds of thrust..

1961 November 16 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Second decision on launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: McNamara,

von Braun,

Webb.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned space station.

Golovin Committe studies launch vehicles through summer, but found the issue to be completely entertwined with mode (earth-orbit, lunar-orbit, lunar-surface rendezvous or direct flight. Two factions: large solids for direct flight; all-chemical with 4 or 5 F-1's in first stage for rendezvous options. In the end Webb and McNamara ordered development of C-4 and as a backup, in case of failure of F-1 in development, build of 6.1 m+ solid rocket motors by USAF.

1961 November 20 - . LV Family: Saturn V. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-5.

- Rosen Group recommends direct ascent for the lunar landing mission mode - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Holmes, Brainard, Rosen, Milton. Program: Apollo. Milton W. Rosen, Director of Launch Vehicles and Propulsion, NASA Office of Manned Space Flight (OMSF), submitted to D. Brainerd Holmes, Director, OMSF, the report of the working group which had been set up on November 6.. Additional Details: here....

1961 November 29-30 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Emergency switchover from Saturn to Apollo guidance as backup discussed - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Guidance. On a visit to Marshall Space Flight Center by MIT Instrumentation Laboratory representatives, the possibility was discussed of emergency switchover from Saturn to Apollo guidance systems as backup for launch vehicle guidance..

1961 December 4 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rosen working group on launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Holmes, Brainard,

Rosen, Milton.

Program: Apollo.

NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., commented to D. Brainerd Holmes, Director, Office of Manned Space Flight, on the report of the Rosen working group on launch vehicles, which had been submitted on November 20. Seamans expressed himself as essentially in accord with the group's recommendations.

1961 December 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Boeing named contractor for Saturn C-5 first stage (S-IC) - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

NASA announced that The Boeing Company had been selected for negotiations as a possible prime contractor for the first stage (S-IC) of the advanced Saturn launch vehicle. The S-IC stage, powered by five F-1 engines, would be 35 feet in diameter and about 140 feet high. The $300-million contract, to run through 1966, called for the development, construction, and testing of 24 flight stages and one ground test stage. The booster would be assembled at the NASA Michoud Operations Plant near New Orleans, La., under the direction of the Marshall Space Flight Center.

1961 December 20 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Douglas named contractor for Saturn S-IVB stage - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

NASA announced that Douglas Aircraft had been selected for negotiation of a contract to modify the Saturn S-IV stage by installing a single 200,000-pound-thrust, Rocketdyne J-2 liquid-hydrogen/liquid-oxygen engine instead of six 15,000-pound-thrust P. & W. hydrogen/oxygen engines. Known as S-IVB, this modified stage will be used in advanced Saturn configurations for manned circumlunar Apollo missions.

1962 January 5 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Three-man Apollo spacecraft, Saturn C-5 launch vehicle announced - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing. NASA made public the drawings of the three-man Apollo spacecraft to be used in the lunar landing development program, On January 9, NASA announced its decision that the Saturn C-5 would be the lunar launch vehicle..

1962 February 14 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Initial contract with Boeing leading to the first stage S-IC of the Saturn C-5 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA signed a contract with The Boeing Company for indoctrination, familiarization, and planning, expected to lead to a follow-on contract for design, development, manufacture, test, and launch operations of the first stage S-IC of the Saturn C-5 launch vehicle.

1962 March 18 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Saturn C-5 first launch scheduled in the last quarter of 1965 - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Marshall Space Flight Center's latest schedule on the Saturn C-5 called for the first launch in the last quarter of 1965 and the first manned launch in the last quarter of 1967. If the C-5 could be man-rated on the eighth research and development flight in the second quarter of 1967, the spacecraft lead time would be substantially reduced.

1962 April 2-3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Meeting at NASA Headquarters reviews the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) technique for Project Apollo - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Geissler,

Horn,

Maynard,

Shea.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

CSM LES,

CSM Recovery,

CSM SPS,

CSM Television.

A meeting to review the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) technique as a possible mission mode for Project Apollo was held at NASA Headquarters. Representatives from various NASA offices attended: Joseph F. Shea, Eldon W. Hall, William A. Lee, Douglas R. Lord, James E. O'Neill, James Turnock, Richard J. Hayes, Richard C. Henry, and Melvyn Savage of NASA Headquarters; Friedrich O. Vonbun of Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC); Harris M. Schurmeier of Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Arthur V. Zimmeman of Lewis Research Center; Jack Funk, Charles W. Mathews, Owen E. Maynard, and William F. Rector of MSC; Paul J. DeFries, Ernst D. Geissler, and Helmut J. Horn of Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC); Clinton E. Brown, John C. Houbolt, and William H. Michael, Jr., of Langley Research Center; and Merrill H. Mead of Ames Research Center. Each phase of the LOR mission was discussed separately.

The launch vehicle required was a single Saturn C-5, consisting of the S-IC, S-II, and S-IVB stages. To provide a maximum launch window, a low earth parking orbit was recommended. For greater reliability, the two-stage-to-orbit technique was recommended rather than requiring reignition of the S-IVB to escape from parking orbit.

The current concepts of the Apollo command and service modules would not be altered. The lunar excursion vehicle (LEV), under intensive study in 1961, would be aft of the service module and in front of the S-IVB stage. For crew safety, an escape tower would be used during launch. Access to the LEV would be provided while the entire vehicle was on the launch pad.

Both Apollo and Saturn guidance and control systems would be operating during the launch phase. The Saturn guidance and control system in the S-IVB would be "primary" for injection into the earth parking orbit and from earth orbit to escape. Provisions for takeover of the Saturn guidance and control system should be provided in the command module. Ground tracking was necessary during launch and establishment of the parking orbit, MSFC and GSFC would study the altitude and type of low earth orbit.

The LEV would be moved in front of the command module "early" in the translunar trajectory. After the S-IVB was staged off the spacecraft following injection into the translunar trajectory, the service module would be used for midcourse corrections. Current plans were for five such corrections. If possible, a symmetric configuration along the vertical center line of the vehicle would be considered for the LEV. Ingress to the LEV from the command module should be possible during the translunar phase. The LEV would have a pressurized cabin capability during the translunar phase. A "hard dock" mechanism was considered, possibly using the support structure needed for the launch escape tower. The mechanism for relocation of the LEV to the top of the command module required further study. Two possibilities were discussed: mechanical linkage and rotating the command module by use of the attitude control system. The S-IVB could be used to stabilize the LEV during this maneuver.

The service module propulsion would be used to decelerate the spacecraft into a lunar orbit. Selection of the altitude and type of lunar orbit needed more study, although a 100-nautical-mile orbit seemed desirable for abort considerations.

The LEV would have a "point" landing (±½ mile) capability. The landing site, selected before liftoff, would previously have been examined by unmanned instrumented spacecraft. It was agreed that the LEV would have redundant guidance and control capability for each phase of the lunar maneuvers. Two types of LEV guidance and control systems were recommended for further analysis. These were an automatic system employing an inertial platform plus radio aids and a manually controlled system which could be used if the automatic system failed or as a primary system.

The service module would provide the prime propulsion for establishing the entire spacecraft in lunar orbit and for escape from the lunar orbit to earth trajectory. The LEV propulsion system was discussed and the general consensus was that this area would require further study. It was agreed that the propulsion system should have a hover capability near the lunar surface but that this requirement also needed more study.

It was recommended that two men be in the LEV, which would descend to the lunar surface, and that both men should be able to leave the LEV at the same time. It was agreed that the LEV should have a pressurized cabin which would have the capability for one week's operation, even though a normal LOR mission would be 24 hours. The question of lunar stay time was discussed and it was agreed that Langley should continue to analyze the situation. Requirements for sterilization procedures were discussed and referred for further study. The time for lunar landing was not resolved.

In the discussion of rendezvous requirements, it was agreed that two systems be studied, one automatic and one providing for a degree of manual capability. A line of sight between the LEV and the orbiting spacecraft should exist before lunar takeoff. A question about hard-docking or soft-docking technique brought up the possibility of keeping the LEV attached to the spacecraft during the transearth phase. This procedure would provide some command module subsystem redundancy.

Direct link communications from earth to the LEV and from earth to the spacecraft, except when it was in the shadow of the moon, was recommended. Voice communications should be provided from the earth to the lunar surface and the possibility of television coverage would be considered.

A number of problems associated with the proposed mission plan were outlined for NASA Center investigation. Work on most of the problems was already under way and the needed information was expected to be compiled in about one month.

(This meeting, like the one held February 13-15, was part of a continuing effort to select the lunar mission mode).

1962 April 24 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rosen recommends Saturn C-5 design and lunar orbit rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Rosen, Milton.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

CSM Recovery,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Milton W. Rosen, NASA Office of Manned Space Flight Director of Launch Vehicles and Propulsion, recommended that the S-IVB stage be designed specifically as the third stage of the Saturn C-5 and that the C-5 be designed specifically for the manned lunar landing using the lunar orbit rendezvous technique. The S-IVB stage would inject the spacecraft into a parking orbit and would be restarted in space to place the lunar mission payload into a translunar trajectory. Rosen also recommended that the S- IVB stage be used as a flight test vehicle to exercise the command module (CM), service module (SM), and lunar excursion module (LEM) (previously referred to as the lunar excursion vehicle (LEV)) in earth orbit missions. The Saturn C-1 vehicle, in combination with the CM, SM, LEM, and S-IVB stage, would be used on the most realistic mission simulation possible. This combination would also permit the most nearly complete operational mating of the CM, SM, LEM, and S-IVB prior to actual mission flight.

1962 May 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Saturn F-1 engine first fired at full power - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The F-1 engine was first fired at full power more than 1.5 million pounds of thrust) for 2.5 minutes at Edwards Rocket Site, Calif..

1962 May 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Mobile launcher concept for the Saturn C-5 approved - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The Manned Space Flight Management Council approved the mobile launcher concept for the Saturn C-5 at Launch Complex 39, Merritt Island, Fla..

1962 June - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Study of repair of J-2 engine in space - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

Five NASA scientists, dressed in pressure suits, completed an exploratory study at Rocketdyne Division of the feasibility of repairing, replacing, maintaining, and adjusting components of the J-2 rocket while in space. The scientific team also investigated the design of special maintenance tools and the effectiveness of different pressure suits in performing maintenance work in space.

1962 July 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contracts to Rocketdyne for production of the Saturn's F-1 and J-2 rocket engines - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA awarded three contracts totaling an estimated $289 million to NAA's Rocketdyne Division for the further development and production of the F-1 and J-2 rocket engines..

1962 July 21 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo advanced Saturn launch complex northwest of Cape Canaveral - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA announced plans for an advanced Saturn launch complex to be built on 80,000 acres northwest of Cape Canaveral. The new facility, Launch Complex 39, would include a building large enough for the vertical assembly of a complete Saturn launch vehicle and Apollo spacecraft.

1962 August 8 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contract to Douglas for the S-IVB stage - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

NASA awarded a $141.1 million contract to the Douglas Aircraft Company for design, development, fabrication, and testing of the S-IVB stage, the third stage of the Saturn C-5 launch vehicle. The contract called for 11 S-IVB units, including three for ground tests, two for inert flight, and six for powered flight.

1962 August - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Structural requirements for Apollo lunar excursion module adapter established - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NAA finished structural requirements for a lunar excursion module adapter mating the 154-inch diameter service module to the 260-inch diameter S-IVB stage..

1962 September 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Plans for Apollo Mississippi Test Facility - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA announced that it had completed preliminary plans for the development of the $500-million Mississippi Test Facility. The first phase of a three-phase construction program would begin in 1962 and would include four test stands for static-firing the Saturn C-5 S-IC and S-II stages; about 20 support and service buildings would be built in the first phase. A water transportation system had been selected, calling for improvement of about 15 miles of river channel and construction of about 15 miles of canals at the facility. Additional Details: here....

1962 September - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo spacecraft weights - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

LM Weight.

The Apollo spacecraft weights had been apportioned within an assumed 90,000 pound limit. This weight was termed a "design allowable." A lower target weight for each module had been assigned. Achievement of the target weight would allow for increased fuel loading and therefore greater operational flexibility and mission reliability. The design allowable for the command module was 9,500 pounds; the target weight was 8,500 pounds. The service module design allowable was 11,500 pounds; the target weight was 11,000 pounds. The S-IVB adapter design allowable and target weight was 3,200 pounds. The amount of service module useful propellant was 40,300 pounds design allowable; the target weight was 37,120 pounds. The lunar excursion module design allowable was 25,500 pounds; the target weight was 24,500 pounds.

1962 October 4 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First full-duration static firing of the Apollo J-2 engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Rocketdyne Division successfully completed the first full-duration (250-seconds) static firing of the J-2 engine..

1962 October 30 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contract for production of the S-II stage signed - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA announced the signing of a contract with the Space and Information Systems Division of NAA for the development and production of the second stage (S-II) of the Saturn C-5 launch vehicle. The $319.9-million contract, under the direction of Marshall Space Flight Center, covered the production of nine live flight stages, one inert flight stage, and several ground-test units for the advanced Saturn launch vehicle. NAA had been selected on September 11, 1961, to develop the S-II.

1962 October - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Technique for separating the Apollo command and service modules during an abort - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM RCS.

The technique tentatively selected by NAA for separating the command and service modules from lower stages during an abort consisted of firing four 2000-pound-thrust posigrade rockets mounted on the service module adapter. With this technique, no retrorockets would be needed on the S-IV or S-IVB stages. Normal separation from the S-IVB would be accomplished with the service module reaction control system.

1962 October 31 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contract for the S-IVB stage for use in the Saturn C- 1B - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA announced that the Douglas Aircraft Company had been awarded a $2.25million contract to modify the S-IVB stage for use in the Saturn C- 1B program..

1962 December 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Four firms to design the Apollo Vertical Assembly Building (VAB) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, acting for NASA, awarded a $3.332 million contract to four New York architectural engineering firms to design the Vertical Assembly Building (VAB) at Cape Canaveral. The massive VAB became a space-age hangar, capable of housing four complete Saturn V launch vehicles and Apollo spacecraft where they could be assembled and checked out. The facility would be 158.5 meters (520 feet high) and would cost about $100 million to build. Subsequently, the Corps of Engineers selected Morrison-Knudson Company, Perini Corp., and Paul Hardeman, Inc., to construct tile VAB.

1962 December 4 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First test of the Apollo main parachute system - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The first test of the Apollo main parachute system, conducted at the Naval Air Facility, El Centro, Calif., foreshadowed lengthy troubles with the landing apparatus for the spacecraft. One parachute failed to inflate fully, another disreefed prematurely, and the third disreefed and inflated only after some delay. No data reduction was possible because of poor telemetry. North American was investigating.

1963 January 22 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Orbiting Space Station. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Spacecraft: LORL.

Addressing an Institute of Aerospace Science meeting in New York, George von Tiesenhausen, Chief of Future Studies at NASA's Launch Operations Center, stated that by 1970 the United States would need an orbiting space station to launch and repair spacecraft. The station could also serve as a manned scientific laboratory. In describing the 91-m-long, 10-m-diameter structure, von Tiesenhausen said that the station could be launched in two sections using Saturn C-5 vehicles. The sections would be joined once in orbit.

1963 February 12 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Marion Power Shovel selected to build the Saturn V crawler-transport - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA selected the Marion Power Shovel Company to design and build the crawler-transport, a device to haul the Apollo space vehicle (Saturn V, complete with spacecraft and associated launch equipment) from the Vertical Assembly Building to the Merritt Island, Fla., launch pad, a distance of about 5.6 kilometers (3.5 miles). The crawler would be 39.6 meters (130 feet) long, 35 meters (115 feet) wide, and 6 meters (20 feet) high, and would weight 2.5 million kilograms (5.5 million pounds). NASA planned to buy two crawlers at a cost of $4 to 5 million each. Formal negotiations began on February 20 and the contract was signed on March 29.

1963 February 25 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Formal contract with Boeing for the S-IC - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA announced the signing of a formal contract with The Boeing Company for the S-IC (first stage) of the Saturn V launch vehicle, the largest rocket unit under development in the United States. The $418,820,967 agreement called for the development and manufacture of one ground test and ten flight articles. Preliminary development of the S-IC, which was powered by five F-1 engines, had been in progress since December 1961 under a $50 million interim contract. Booster fabrication would take place primarily at the Michoud Operations Plant, New Orleans, La., but some advance testing would be done at MSFC and the Mississippi Test Operations facility.

1963 April 17 - . LV Family: Saturn V, Saturn I, Titan.

- Large Solid Rocket Motor Program (Program 623A) begun. - .

The Defense Department announced the selection of Thiokol Chemical Corporation, Aerojet-General Corporation, and Lockheed Propulsion Company to conduct work on the development of large solid-propellant motors as part of the Space Systems Division's Large Solid Rocket Motor Program (Program 623A). Development work was divided into four tasks: (1) Thiokol and Aerojet-General were to develop 260-inch diameter, solid rocket motors of 3 million pounds of thrust for demonstration static firings; (2) Thiokol was to work on a 156-inch, 3 million-pound thrust, two-segment solid rocket motor; (3) Thiokol was to develop and static fire a 156-inch, one-segment solid rocket motor of one million pounds thrust demonstrating thrust vector control (TVC) through movable nozzles; and (4) Lockheed was to static fire a 156-inch, single segment solid rocket motor of one million pounds thrust that demonstrated TVC through jet tabs.

1963 April 30 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Earth parking orbit requirements - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Apollo Spacecraft Mission Trajectory Sub-Panel discussed earth parking orbit requirements for the lunar mission. The maximum number of orbits was fixed by the S-IVB's 4.5-hour duration limit. Normally, translunar injection (TLI) would be made during the second orbit. The panel directed North American to investigate the trajectory that would result from injection from the third, or contingency, orbit. The contractor's study must reckon also with the effects of a contingency TLI upon the constraints of a free return trajectory and fixed lunar landing sites.

1963 May 20-22 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Status report on the Apollo LEM landing gear design and Apollo LEM stowage height - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Landing Gear.

At a meeting on mechanical systems at MSC, Grumman presented a status report on the LEM landing gear design and LEM stowage height. On May 9, NASA had directed the contractor to consider a more favorable lunar surface than that described in the original Statement of Work. Additional Details: here....

1963 June 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Length of the spacecraft-Saturn V adapter had been increased from 8.077 meters to 8.89 meters - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Landing Gear. MSC informed MSFC that the length of the spacecraft-Saturn V adapter had been increased from 807.7 centimeters to 889 centimeters (318 inches to 350 inches). The LEM would be supported in the adapter from a fixed structure on the landing gear..

1963 June 25 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo LEM landing gear design freeze - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Landing Gear.

MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth reported to the MSF Management Council that the LEM landing gear design freeze was now scheduled for August 31. Grumman had originally proposed a LEM configuration with five fixed legs, but LEM changes had made this concept impractical. The weight and overall height of the LEM had increased, the center of gravity had been moved upward, the LEM stability analysis had expanded to cover a wider range of landing conditions, the cruciform descent stage had been selected, and the interpretation of the lunar model had been revised. These changes necessitated a larger gear diameter than at first proposed. This, in turn, required deployable rather than fixed legs so the larger gear could be stored in the Saturn V adapter. MSC had therefore adopted a four-legged deployable gear, which was lighter and more reliable than the five-legged configuration.

1963 July 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Pregnant Guppy FAA certification - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Aero Spacelines' "Pregnant Guppy," a modified Boeing Stratocruiser, won airworthiness certification by the Federal Aviation Agency. The aircraft would be used to transport major Apollo spacecraft and launch vehicle components..

1963 August 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Grumman to design the LEM to have a thrusting capability with the Apollo CSM attached - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM SPS.

North American asked MSC if Grumman was designing the LEM to have a thrusting capability with the CSM attached and, if not, did NASA intend to require the additional effort by Grumman to provide this capability. North American had been proceeding on the assumption that, should the service propulsion system (SPS) fail during translunar flight, the LEM would make any course corrections needed to ensure a safe return trajectory. Additional Details: here....

1963 August 23 - . LV Family: Saturn V.

- Two contracts in its program to develop large-solid-propellant motors (Program 623A). - .

Headquarters Space Systems Division awarded two contracts in its program to develop the technology for large-solid-propellant motors (Program 623A). Thiokol Chemical Corporation and Aerojet-General Corporation received contracts for demonstration static firings of 260-inch diameter, solid-propellant rocket motors of approximately 3 million, pounds thrust. Following the test firings, one of the contractors would be selected to continue development of the 260-inch motor.

1963 October 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Preliminary configuration freeze for the Apollo LEM-adapter arrangement - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Descent Propulsion,

LM Landing Gear.

At a LEM Mechanical Systems Meeting in Houston, Grumman and MSC agreed upon a preliminary configuration freeze for the LEM-adapter arrangement. The adapter would be a truncated cone, 876 centimeters (345 inches) long. The LEM would be mounted inside the adapter by means of the outrigger trusses on the spacecraft's landing gear. This configuration provided ample clearance for the spacecraft, both top and bottom (i.e., between the service propulsion engine bell and the instrument unit of the S-IVB).

At this same meeting, Grumman presented a comparison of radially and laterally folded landing gears (both of 457-centimeter (180-inch) radius). The radial-fold configuration, MSC reported, promised a weight savings of 22-2 kilograms (49 pounds). MSC approved the concept, with an 876-centimeter (345-inch) adapter. Further, an adapter of that length would accommodate a larger, lateral fold gear (508 centimeters (200 inches)), if necessary. During the next several weeks, Grumman studied a variety of gear arrangements (sizes, means of deployment, stability, and even a "bending" gear). At a subsequent LEM Mechanical Systems Meeting, on November 10, Grumman presented data (design, performance, and weight) on several other four-legged gear arrangements - a 457-centimeter (180-inch), radial fold "tripod" gear (i.e., attached to the vehicle by three struts), and 406.4-centimeter (160-inch) and 457-centimeter (180-inch) cantilevered gears. As it turned out, the 406.4-centimeter (160-inch) cantilevered gear, while still meeting requirements demanded in the work statement, in several respects was more stable than the larger tripod gear. In addition to being considerably lighter, the cantilevered design offered several added advantages:

- A reduced stowed height for the LEM from 336.5 to 313.7 centimeters (132.5 to 123.5 inches).

- A shorter landing stroke (50.8 instead of 101.6 centimeters) (20 instead of 40 inches).

- Better protection from irregularities (protuberances) on the surface.

- An alleviation of the gear heating problem (caused by the descent engine's exhaust plume).

- Simpler locking mechanisms.

- A better capability to handle various load patterns on the landing pads.

1963 October 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo Guidance and Performance Sub-Panel first meeting - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Guidance and Performance Sub-Panel, at its first meeting, began coordinating work at MSC and MSFC. The sub-panel outlined tasks for eac Center: MSFC would define the dispersions comprising the launch vehicle performance reserves, prepare a set of typical translunar injection errors for the Saturn V launch vehicle, and give MSC a typical Saturn V guidance computation for injection into an earth parking orbit. MSC would identify the constraints required for free-return trajectories and provide MSFC with details of the MIT guidance method. Further, the two Centers would exchange data each month showing current launch vehicle and spacecraft performance capability. (For operational vehicles, studies of other than performance capability would be based on control weights and would not reflect the current weight status.)

1963 October 31 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First production F-1 engine delivered - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The first production F-1 engine for the Apollo Saturn V was flown from Rocketdyne's Canoga Park, Calif., facility, where it was manufactured, to MSFC aboard Aero Spacelines' "Pregnant Guppy.".

1963 November 12 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contract for the construction of Saturn V LC-39A - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA awarded a $19.2 million contract to Blount Brothers Corporation and M. M. Sundt Construction Company for the construction of Pad A, part of the Saturn V Launch Complex 39 at LOC..

1963 November 12 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Supplemental agreement for the S-IC stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The Boeing Company and NASA signed a $27.4 million supplemental agreement to the contract for development, fabrication, and test of the S-IC (first) stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle..

1963 November 27 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- First long-duration test firing of Apollo J-2 engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. At its Santa Susana facility, Rocketdyne conducted the first long-duration (508 seconds) test firing of a J-2 engine. In May 1962 the J-2's required firing time was increased from 250 to 500 seconds..

1963 December 9 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Space required in the S-IVB instrument unit for different Apollo LEM landing gear designs defined - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. ASPO requested that Grumman make a layout for transmittal to MSFC showing space required in the S-IVB instrument unit for 406.4- and 457-centimeter (160- and 180-inch) cantilevered gears and for 508-centimeter (200-inch)-radius lateral fold gears..

1963 December 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Extension of Apollo systems to permit more extensive exploration of the lunar surface. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Shea,

von Braun.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM Shelter,

Apollo LM Taxi.

MSFC Director Wernher von Braun described to Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager Joseph F. Shea a possible extension of Apollo systems to permit more extensive exploration of the lunar surface. Huntsville's concept, called the Integrated Lunar Exploration System, involved a dual Saturn V mission (with rendezvous in lunar orbit) to deliver an integrated lunar taxi/shelter spacecraft to the Moon's surface. Additional Details: here....

1964 February 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Lockheed recommendations on a scientific space station program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: LORL.

The Lockheed-California Company released details of its recommendations to MSC on a scientific space station program. The study concluded that a manned station with a crew of 24 could be orbiting the Earth in 1968. Total cost of the program including logistics spacecraft and ground support was estimated at $2.6 billion for five years' operation. Lockheed's study recommended the use of a Saturn V to launch the unmanned laboratory into orbit and then launching a manned logistics vehicle to rendezvous and dock at the station.

1964 March 30 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Contract for production of 76 F-1 engines - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. MSFC awarded Rocketdyne a definitive contract (valued at $158.4 million) for the production of 76 F-1 engines for the first stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle and for delivery of ground support equipment..

1964 April - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rotating manned orbital research laboratory for a Saturn V launch vehicle. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Spacecraft: LORL.

A study to recommend, define, and substantiate a logical approach for establishing a rotating manned orbital research laboratory for a Saturn V launch vehicle was made for MSC. The study was performed by the Lockheed-California Company, Burbank, California. It was based on the proposition that a large rotating space station would be one method by which the United States could maintain its position as a leader in space technology. Additional Details: here....

1964 May 28 - . LV Family: Saturn I, Saturn V. Launch Vehicle: Saturn INT-27, Saturn V-25(S)B, Saturn V-25(S)U.

- 156-inch solid-propellant rocket motor fired for the first time. - .

Lockheed Propulsion Company test fired a 156-inch diameter, solid-propellant rocket motor for the first time. The one-segment test motor (156-3-L), with tab jet thrust vector control, produced more than 900,000 pounds of thrust during its 110-second firing. The test was conducted as part of the Space Systems Division's Large Solid Rocket Motor research and development program (Program 623A).

1964 September 10 - . LV Family: Saturn V.

- Lewis Research Center (LeRC) responsible for the large solid-rocket motor development program. - .

NASA announced that its Lewis Research Center (LeRC) would assumed management responsibility for the large solid-rocket motor development program. NASA would take over the 260-inch diameter solid-motor development program from Space Systems Division, and the Aerojet-General and Thiokol developed contracts initiated by SSD in June 1963 were to be transferred to NASA. The 156-inch diameter solid-motor program would remain under SSD control.

1964 October 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Plan to verify the Apollo CM's radiation shielding - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Block II.

MSC's Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO) approved a plan (put forward by the MSC Advanced Spacecraft Technology Division to verify the CM's radiation shielding. Checkout of the radiation instrumentation would be made during manned earth orbital flights. The spacecraft would then be subjected to a radiation environment during the first two unmanned Saturn V flights. These missions, 501 and 502, with apogees of about 18,520 km (10,000 nm), would verify the shielding. Gamma probe verification, using spacecraft 008, would be performed in Houston during 1966. Only Block I CM's would be used in these ground and flight tests. Radiation shielding would be unaffected by the change to Block II status.

1964 October 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo guidance and control interfaces - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Block II.

The Guidance and Control Implementation Sub-Panel of the MSC-MSFC Flight Mechanics Panel defined the guidance and control interfaces for Block I and II missions. In Block II missions the CSM's guidance system would guide the three stages of the Saturn V vehicle; it would control the S- IVB (third stage) and the CSM while in earth orbit; and it would perform the injection into a lunar trajectory. In all of this, the CSM guidance backed up the Saturn ST-124 platform. Actual sequencing was performed by the Saturn V computer.

1964 November 12-19 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Disagreement on number of reentry tests to qualify Apollo CM heatshield - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield.

There appeared to be some confusion and/or disagreement concerning whether one or two successful Saturn V reentry tests were required to qualify the CM heatshield. A number of documents relating to instrumentation planning for the 501 and 502 flight indicated that two successful reentries would be required. The preliminary mission requirements document indicated that only a single successful reentry trajectory would be necessary. The decision would influence the measurement range capability of some heatshield transducers and the mission planning activity being conducted by the Apollo Trajectory Support Office. The Structures and Mechanics Division had been requested to provide Systems Engineering with its recommendation.

1964 November 19-26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Apollo procedural rules for translunar injection - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The MSC-Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Guidance and Control Implementation Sub-Panel set forth several procedural rules for translunar injection (TLI):

- Once the S-IVB ignition sequence was started, the spacecraft would not be able to halt the maneuver. (This would occur about 427 sec before the stage's J-2 engine achieved 90 percent of its thrust capability.)

- Because the spacecraft would receive no signal from the instrument unit (IU), the exact time of sequence initiation must be relayed from the ground.

- The vehicle's roll attitude would be reset prior to injection.

- And when the spacecraft had control of the vehicle, the IU would not initiate the ignition sequence.

1964 December 4 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Battleship S-IVB second stage static-fired - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.