Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

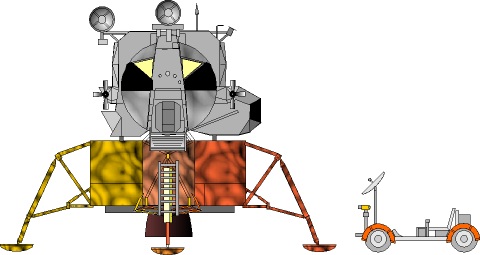

Apollo LM

Apollo LM

Credit: © Mark Wade

AKA: LEM;Lunar Excursion Module;Lunar Module. Status: Operational 1968. First Launch: 1968-01-22. Last Launch: 1972-12-07. Number: 10 . Thrust: 44.04 kN (9,901 lbf). Gross mass: 14,696 kg (32,399 lb). Unfuelled mass: 4,173 kg (9,199 lb). Specific impulse: 311 s. Height: 6.37 m (20.89 ft). Span: 9.07 m (29.75 ft).

Following the decision to use the lunar orbit rendezvous method to get to the moon, Grumman received the contract to develop the lunar module, which would take the first men to the surface to the moon. If funding had been available, modified lunar modules (dubbed LM Taxi, LM Shelter, and LM Truck) would have been used to set up the first lunar bases.

Unit Cost $: 50.000 million. Crew Size: 2. Habitable Volume: 6.65 m3. Spacecraft delta v: 4,700 m/s (15,400 ft/sec). Electric System: 50.00 kWh.

| Apollo LM DS American manned spacecraft module. 10 launches, 1968.01.22 (Apollo 5) to 1972.12.07 (Apollo 17). |

| Apollo LM AS American manned spacecraft module. 10 launches, 1968.01.22 (Apollo 5) to 1972.12.07 (Apollo 17). |

| LM Langley Lighter American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. This early open-cab Langley design used cryogenic propellants. The cryogenic design was estimated to gross 3,284 kg - to be compared with the 15,000 kg / 2 man LM design that eventually was selected. |

| LM Langley Light American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. This early open-cab single-crew Langley lunar lander design used storable propellants, resulting in an all-up mass of 4,372 kg. |

| LM Langley Lightest American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. Extremely light-weight open-cab lunar module design considered in early Langley studies. |

| Apollo ULS American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1962. An Apollo unmanned logistic system to aid astronauts on a lunar landing mission was studied. |

| Apollo LLRV American manned lunar lander test vehicle. Bell Aerosystems initially built two manned lunar landing research vehicles (LLRV) for NASA to assess the handling characteristics of Apollo LM-type vehicles on earth. |

| Apollo LLRF American Lunar Landing Research Facility. The huge structure (76.2 m high and 121.9 m long) was used to explore techniques and to forecast various problems of landing on the moon. |

| Apollo LM Shelter American manned lunar habitat. Cancelled 1968. The LM Shelter was essentially an Apollo LM lunar module with ascent stage engine and fuel tanks removed and replaced with consumables and scientific equipment for 14 days extended lunar exploration. |

| Apollo LM Taxi American manned lunar lander. Cancelled 1968. The LM Taxi was essentially the basic Apollo LM modified for extended lunar surface stays. |

| Apollo LM Truck American lunar logistics spacecraft. Cancelled 1968. The LM Truck was an LM Descent stage adapted for unmanned delivery of payloads of up to 5,000 kg to the lunar surface in support of a lunar base using Apollo technology. |

| Apollo LM Lab American manned space station. Study 1965. Use of the Apollo LM as an earth-orbiting laboratory was proposed for Apollo Applications Program missions. |

| Apollo LM CSD American manned combat spacecraft. Study 1965. The Apollo Lunar Module was considered for military use in the Covert Space Denial role in 1964. |

| Apollo LMSS American manned space station. Cancelled 1967. Under the Apollo Applications Program NASA began hardware and software procurement, development, and testing for a Lunar Mapping and Survey System. The system would be mounted in an Apollo CSM. |

| Apollo LASS S-IVB American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1966. The Douglas Company (DAC) proposed the "Lunar Application of a Spent S-IVB Stage (LASS)". The LASS concept required a landing gear on a S-IVB Stage. |

| Apollo LTA American technology satellite. 3 launches, 1967.11.09 (LTA-10R) to 1968.12.21 (LTA-B). Apollo Lunar module Test Articles were simple mass/structural models of the Lunar Module. |

| LM 1 (LEM 1) Null |

| Apollo LPM American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1968. The unmanned portion of the Lunar Surface Rendezvous and Exploration Phase of Apollo envisioned in 1969 was the Lunar Payload Module (LPM). |

| Apollo ELS American manned lunar habitat. Cancelled 1968. The capabilities of a lunar shelter not derived from Apollo hardware were surveyed in the Early Lunar Shelter Study (ELS), completed in February 1967 by AiResearch. |

| Apollo LASS American manned lunar habitat. Cancelled 1968. In the LASS (LM Adapter Surface Station) lunar shelter concept, the LM ascent stage was replaced by an SLA 'mini-base' and the position of the Apollo Service Module (SM) was reversed. |

| LM 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12 (LEM 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12) Null |

| Apollo ALSEP American lunar lander. 7 launches, 1969.07.16 (EASEP) to 1972.12.07 (ALSEP). ALSEP (Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package) was the array of connected scientific instruments left behind on the lunar surface by each Apollo expedition. |

| Apollo LRM American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1969. Grumman proposed to use the LM as a lunar reconnaissance module. But NASA had already considered this and many other possibilities (Apollo MSS, Apollo LMSS); and there was no budget available for any of them. |

| Apollo MET American lunar hand cart. Flown 1971. NASA designed the MET lunar hand cart to help with problems such as the Apollo 12 astronauts had in carrying hand tools, sample boxes and bags, a stereo camera, and other equipment on the lunar surface. |

Family: Lunar Landers, Moon. Country: USA. Engines: TR-201. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing, Apollo LM DS, Apollo LM AS. Launch Vehicles: Little Joe II, Saturn I, Saturn IB, Saturn V. Propellants: N2O4/Aerozine-50. Projects: Apollo. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral, Cape Canaveral LC37B, Cape Canaveral LC39A, Cape Canaveral LC39B. Agency: NASA, Grumman. Bibliography: 148, 16, 160, 183, 2, 22, 2429, 2430, 2431, 2432, 2433, 2434, 2437, 2438, 2439, 2440, 2441, 2442, 2443, 2444, 2445, 2447, 2448, 2449, 2450, 2451, 2452, 2575, 26, 27, 33, 6, 60, 66, 6347, 12053.

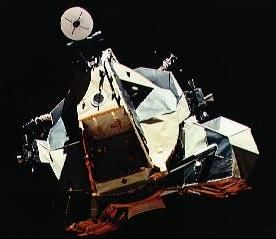

| LM on Moon Credit: NASA |

| LM Evolution LM Evolution. From left: July 1962, LOR decision, 220 inch Saturn IVB; November 1962, Grumman contract award, 260-inch S-IVB; 1963; 1967; as flown. Credit: © Mark Wade |

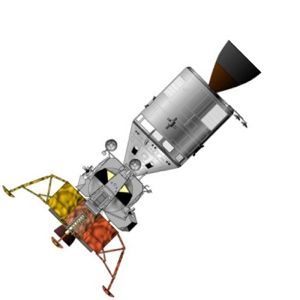

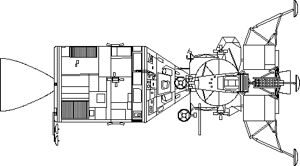

| Apollo CSM / LM Apollo Command Service Module and Lunar Module Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo 10 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Apollo Lunar Module Credit: © Mark Wade |

| LM Ascent Stage Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 16 1/6 G leap Apollo astronaut demonstrates low lunar gravity. Credit: NASA |

| Apollo CSM and LM Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apolo LM Credit: © Mark Wade |

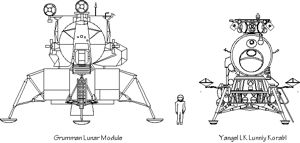

| LM vs LK US Lunar Module compared to Soviet LK lunar lander Credit: © Mark Wade |

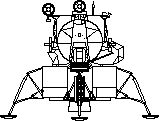

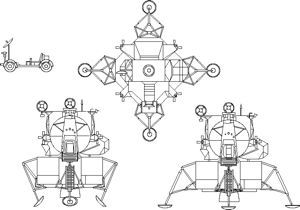

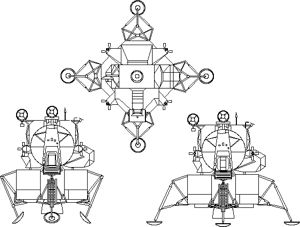

| Lunar Module 3 view Credit: © Mark Wade |

1959 April 7 - .

- Research into rendezvous techniques - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan requested $3 million for research into rendezvous techniques as part of the NASA budget for Fiscal Year 1960. In subsequent hearings, DeMarquis D. Wyatt, Assistant to the NASA Director of Space Flight Development, explained that these funds would be used to resolve certain key problems in making space rendezvous practical. Among these were the establishment of referencing methods for fixing the relative positions of two vehicles in space; the development of accurate, lightweight target-acquisition equipment to enable the supply craft to locate the space station; the development of very accurate guidance and control systems to permit precisely determined flight paths; and the development of sources of controlled power.

1959 December 8-9 - .

- Configurations for manned lunar landing by direct ascent - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Several possible configurations for a manned lunar landing by direct ascent being studied at the Lewis Research Center were described to the Research Steering Committee by Seymour C. Himmel. A six-stage launch vehicle would be required, the first three stages to boost the spacecraft to orbital speed, the fourth to attain escape speed, the fifth for lunar landing, and the sixth for lunar escape with a 10,000-pound return vehicle. One representative configuration had an overall height of 320 feet. H. H. Koelle of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency argued that orbital assembly or refueling in orbit (earth orbit rendezvous) was more flexible, more straightforward, and easier than the direct ascent approach. Bruce T. Lundin of the Lewis Research Center felt that refueling in orbit presented formidable problems since handling liquid hydrogen on the ground was still not satisfactory. Lewis was working on handling cryogenic fuels in space.

1960 January - .

- Manned lunar landing and return (MALLAR) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Chance Vought Corporation completed a company-funded, independent, classified study on manned lunar landing and return (MALLAR), under the supervision of Thomas E. Dolan. Booster limitations indicated that earth orbit rendezvous would be necessary. A variety of lunar missions were described, including a two-man, 14-day lunar landing and return. This mission called for an entry vehicle of 6,600 pounds, a mission module of 9,000 pounds, and a lunar landing module of 27,000 pounds. It incorporated the idea of lunar orbit rendezvous though not specifically by name.

1960 Spring - .

- Chance Vought study of the lunar orbit rendezvous method - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, Apollo Lunar Landing, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. Thomas E. Dolan of the Chance Vought Corporation prepared a company-funded design study of the lunar orbit rendezvous method for accomplishing the lunar landing mission..

1960 April 5 - .

- Houbolt paper on rendezvous in space with minimum expenditure of fuel - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Houbolt.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

John C. Houbolt of the Langley Research Center presented a paper at the National Aeronautical Meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers in New York City in which the problems of rendezvous in space with the minimum expenditure of fuel were considered. Additional Details: here....

1960 April - .

- MIT Report on space guidance and control design - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Guidance,

LM Source Selection.

A study report was issued by the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory on guidance and control design for a variety of space missions. This report, approved by C. Stark Draper, Director of the Laboratory, showed that a vehicle, manned or unmanned, could have significant onboard navigation and guidance capability.

1960 May 5 - .

- STG and Grumman discuss advanced spacecraft programs - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Faget,

Gilruth.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

Robcrt R. Gilruth, Paul E. Purser, James A. Chamberlin, Maxime A. Faget, and H. Kurt Strass of STG met with a group from the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation to discuss advanced spacecraft programs. Grumman had been working on guidance requirements for circumlunar flights under the sponsorship of the Navy and presented Strass with a report of this work.

1960 October 17 - .

- Formation of a working group on the manned lunar landing program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

In a memorandum to Abe Silverstein, Director of NASA's Office of Space Flight Programs, George M. Low, Chief of Manned Space Flight, described the formation of a working group on the manned lunar landing program: "It has become increasingly apparent that a preliminary program for manned lunar landings should be formulated. This is necessary in order to provide a proper justification for Apollo, and to place Apollo schedules and technical plans on a firmer foundation.

"In order to prepare such a program, I have formed a small working group, consisting of Eldon Hall, Oran Nicks, John Disher, and myself. This group will endeavor to establish ground rules for manned lunar landing missions; to determine reasonable spacecraft weights; to specify launch vehicle requirements; and to prepare an integrated development plan, including the spacecraft, lunar landing and takeoff system, and launch vehicles. This plan should include a time-phasing and funding picture, and should identify areas requiring early studies by field organizations."

1960 December 10 - .

- Lunar orbit method of accomplishing the lunar landing mission - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. Representatives of the Langley Research Center briefed members of STG on the lunar orbit method of accomplishing the lunar landing mission..

1960 December 14 - .

- Seamans briefed on the lunar orbit rendezvous method - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Seamans.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Associate Administrator of NASA Robert C. Seamans, Jr., and his staff were briefed by Langley Research Center personnel on the rendezvous method as it related to the national space program. Clinton E. Brown presented an analysis made by himself and Ralph W. Stone, Jr., describing the general operational concept of lunar orbit rendezvous for the manned lunar landing. The advantages of this plan in contrast with the earth orbit rendezvous method, especially in reducing launch vehicle requirements, were illustrated. Others discussing the rendezvous were John C. Houbolt, John D. Bird, and Max C. Kurbjun.

1960 December 29 - .

- Grumman began work on a lunar orbit rendezvous study - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation began work on a company- funded lunar orbit rendezvous feasibility study..

1961 January 5-6 - .

- Manned lunar landing discussed with Space Exploration Program Council - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

During a meeting of the Space Exploration Program Council at NASA Headquarters, the subject of a manned lunar landing was discussed. Following presentations on earth orbit rendezvous (Wernher von Braun, Director of Marshall Space Flight Center), lunar orbit rendezvous (John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center), and direct ascent (Melvyn Savage of NASA Headquarters), the Council decided that NASA should not follow any one of these specific approaches, but should proceed on a broad base to afford flexibility. Another outcome of the discussion was an agreement that NASA should have an orbital rendezvous program which could stand alone as well as being a part of the manned lunar program. A task group was named to define the elements of the program insofar as possible. Members of the group were George M. Low, Chairman, Eldon W. Hall, A. M. Mayo, Ernest O. Pearson, Jr., and Oran W. Nicks, all of NASA Headquarters; Maxime A. Faget of STG; and H. H. Koelle of Marshall Space Flight Center. This group became known as the Low Committee.

1961 January 10 - .

- Conference on lunar orbit rendezvous for the Apollo program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Maynard.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

A conference was held at the Langley Research Center between representatives of STG and Langley to discuss the feasibility of incorporating a lunar orbit rendezvous phase into the Apollo program. Attending the meeting for STG were Robert L. O'Neal, Owen E. Maynard, and H. Kurt Strass, and for the Langley Research Center, John C. Houbolt, Clinton E. Brown, Manuel J. Queijo, and Ralph W. Stone, Jr. The presentation by Houbolt centered on a performance analysis which showed the weight saving to be gained by the lunar rendezvous technique as opposed to the direct ascent mode. According to the analysis, a saving in weight of from 20 to 40 percent could be realized with the lunar orbit rendezvous technique.

1961 January 16-17 - .

- Second meeting of the Low Committee - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

At the second meeting of the Manned Lunar Landing Task Group (Low Committee), a draft position paper was presented by George M. Low, Chairman. A series of reports on launch vehicle capabilities, spacecraft, and lunar program support were presented and considered for possible inclusion in the position paper.

1961 January 24 - .

- Low Committee first draft report - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Manned Lunar Landing Task Group (Low Committee) submitted its first draft report to NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. A section on detailed costs and schedules still was in preparation and a detailed itemized backup report was expected to be available in mid- February.

1961 February 27-25 - .

- NASA Inter-Center meeting on space rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

A NASA inter-Center meeting on space rendezvous was held in Washington, D.C. Air Force and NASA programs were discussed and the status of current studies was presented by NASA Centers. Members of the Langley Research Center outlined the basic concepts of the lunar orbit rendezvous method of accomplishing the lunar landing mission.

1961 March 1-3 - .

- The midterm review of the Apollo feasibility studies was held at STG - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

The midterm review of the Apollo feasibility studies was held at STG. Oral status reports were made by officials of Convair Astronautics Division of the General Dynamics Corporation on March 1, The Martin Company on March 2, and the General Electric Company on March 3. The reports described the work accomplished, problems unsolved, and future plans. Representatives of all NASA Centers attended the meetings, including a majority of the members of the Apollo Technical Liaison Groups. Members of these Groups formed the nucleus of the mid-term review groups which met during the three-day period and compiled lists of comments on the presentations for later discussions with the contractors.

1961 April 19 - .

- Manned Lunar Landing via Rendezvous report - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

A circular, "Manned Lunar Landing via Rendezvous," was prepared by John C. Houbolt from material supplied by himself, John D. Bird, Max C. Kurbjun, and Arthur W. Vogeley, who were members of the Langley Research Center space station subcommittee on rendezvous. Other members of the subcommittee at various times included W. Hewitt Phillips, John M. Eggleston, John A. Dodgen, and William D. Mace.

1961 April 19 - .

- Apollo MORAD, ARP, and MALLIR recommendations - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

Recommendations on immediate steps to be taken so that the three key projects - MORAD (Manned Orbital Rendezvous and Docking), ARP (Apollo Rendezvous Phases), and MALLIR (Manned Lunar Landing Involving Rendezvous) - could get under way were:

- Approve the MORAD project and let a study contract to consider general aspects of the Scout rendezvous vehicle design, definite planning and schedules, and tie down cost estimates more exactly.

- Delegate responsibility to STG to give accelerated consideration to rendezvous aspects of Apollo, tailoring developments to fit directly into the MALLIR project.

- Let a study contract to establish preliminary design, scheduling, and cost figures for the three projects.

1961 May 25 - .

- Lundin Committee to assess Lunar landing mission - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Seamans.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Robert C. Seamans, Jr., NASA's Associate Administrator, requested the Directors of the Office of Launch Vehicle Programs and the Office of Advanced Research Programs to bring together members of their staffs with other persons from NASA Headquarters to assess a wide variety of possible ways of accomplishing the lunar landing mission. This study was to supplement the one being done by the Ad Hoc Task Group for Manned Lunar Landing Study (Fleming Committee) but was to be separate from it. Additional Details: here....

1961 May - .

- Lunar orbit rendezvous plan - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. Basic concepts of the lunar orbit rendezvous plan were presented to the Lundin Committee by John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center..

1961 June 26 - .

- Langley Research Center lunar landing paper - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Maxime A. Faget, Paul E. Purser, and Charles J. Donlan of STG met with Arthur W. Vogeley, Clinton E. Brown, and Laurence K. Loftin, Jr., of Langley Research Center on a "lunar landing" paper. Faget's outline was to be used, with part of the information to be worked up by Vogeley.

1961 June - .

- Lunar orbit rendezvous briefing - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. Members of Langley Research Center briefed the Heaton Committee on the lunar orbit rendezvous method of accomplishing the manned lunar landing mission..

1961 July - .

- Langley simulated spacecraft flights in approaching the moon's surface - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Simulator,

LM Source Selection.

Langley Research Center simulated spacecraft flights at speeds of 8,200 to 8,700 feet per second in approaching the moon's surface. With instruments preset to miss the moon's surface by 40 to 80 miles, pilots with control of thrust and torques about all three axes of the craft learned to establish orbits 10 to 90 miles above the surface, using a graph of vehicle rate of descent and circumferential velocity, an altimeter, and vehicle attitude and rate meters, as reported by Manuel J. Queijo and Donald R. Riley of Langley.

1961 August 23 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Golovin Committee evaluates three rendezvous methods for manned lunar landing - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM ECS,

LM Source Selection.

The Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group (Golovin Committee) notified the Marshal! Space Flight Center (MSFC), Langley Research Center, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) that the Group was planning to undertake a comparative evaluation of three types of rendezvous operations and direct flight for manned lunar landing. Rendezvous methods were earth orbit, lunar orbit, and lunar surface. MSFC was requested to study earth orbit rendezvous, Langley to study lunar orbit rendezvous, and JPL to study lunar surface rendezvous. The NASA Office of Launch Vehicle Programs would provide similar information on direct ascent. Additional Details: here....

1961 September 14 - .

- Studies being done on rendezvous modes for accomplishing a manned lunar landing - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

In a memorandum to the Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group (LLVPG) staff, Harvey Hall of NASA described the studies being done by the Centers on rendezvous modes for accomplishing a manned lunar landing. These studies had been requested from Langley Research Center, Marshall Space Flight Center, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory on August 23. STG was preparing separate documentation on the lunar orbit rendezvous mode. An LLVPG team to undertake a comparative evaluation of rendezvous and direct ascent techniques had been set up. Members of the team included Hall and Norman Rafel of NASA and H. Braham and L. M. Weeks of Aerospace Corporation.

The evaluation would consider:

- Effect of total flight time on specifications and reliability of equipment and on personnel.

- Effect of vehicle system reliability in each case, including the number of engine starts and restarts.

- Dependence on data, data-rate, and distance from ground station for control of assembly and refueling operations

- Launch and injection windows

- Effect of differences in the total weight propelled to earth escape velocity

- Relative merits of lunar gravity and of a lunar base in general versus an orbital station for rendezvous and assembly purposes.

1961 October 31 - .

- Manned Lunar-Landing through use of Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Under the direction of John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center, a two-volume work entitled "Manned Lunar-Landing through use of Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous" was presented to the Golovin Committee (organized on July 20). The study had been prepared by Houbolt, John D. Bird, Arthur W. Vogeley, Ralph W. Stone, Jr., Manuel J. Queijo, William H. Michael, Jr., Max C. Kurbjun, Roy F. Brissenden, John A. Dodgen, William D. Mace, and others of Langley. The Golovin Committee had requested a mission plan using the lunar orbit rendezvous concept. Bird, Michael, and Robert H. Tolson appeared before the Committee in Washington to explain certain matters of trajectory and lunar stay time not covered in the document.

1961 November 15 - .

- Houbolt letter on lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) plan - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Seamans.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

In a letter to NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center presented the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) plan and outlined certain deficiencies in the national booster and manned rendezvous programs. This letter protested exclusion of the LOR plan from serious consideration by committees responsible for the definition of the national program for lunar exploration.

1962 January-June - .

- Grumman study on lunar orbit rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation developed a detailed, company-funded study on the lunar orbit rendezvous technique: characteristics of the system (relative cost of direct ascent, earth orbit rendezvous, and lunar orbit rendezvous); developmental problems (communications, propulsion); and elements of the system (tracking facilities, etc.). Joseph M. Gavin was appointed in the spring to head the effort, and Robert E. Mullaney was designated program manager.

1962 February 6 - .

- Langley presentation of lunar orbit rendezvous - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center and Charles W. Mathews of MSC made a presentation of lunar orbit rendezvous versus earth orbit rendezvous to the Manned Space Flight Management Council..

1962 February 9 - .

- Ad Hoc Lunar Landing Module Working Group - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

Robert R. Gilruth, MSC Director, in a letter to NASA Headquarters, described the Ad Hoc Lunar Landing Module Working Group which was to be under the direction of the Apollo Spacecraft Project Office. The Group would determine what constraints on the design of the lunar landing module were applicable to the effort of the Lewis Research Center. Gilruth asked that Eldon W. Hall represent NASA Headquarters in this Working Group. (At this time, the lunar landing module was conceived as being that part of the spacecraft which would actually land on the moon and which would contain the propulsion system necessary for launch from the lunar surface and injection into transearth trajectory. Pending a decision on the lunar mission mode, the actual configuration of the module was not yet clearly defined.)

1962 March 1 - .

- Chance Vought to study spacecraft rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

NASA Headquarters selected the Chance Vought Corporation of Ling-Temco-Vought, Inc., as a contractor to study spacecraft rendezvous. A primary part of the contract would be a flight simulation study exploring the capability of an astronaut to control an Apollo-type spacecraft.

1962 March 29 - .

- Chance Vought briefed on lunar orbit rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Members of Langley Research Center briefed representatives of the Chance Vought Corporation of Ling- Temco-Vought, Inc., on the lunar orbit rendezvous method of accomplishing the lunar landing mission. The briefing was made in connection with the study contract on spacecraft rendezvous awarded by NASA Headquarters to Chance Vought on March 1.

1962 March - .

- Preliminary Apollo program schedules - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

A small group within the MSC Apollo Spacecraft Project Office developed a preliminary program schedule for three approaches to the lunar landing mission: earth orbit rendezvous, direct ascent, and lunar orbit rendezvous. The exercise established a number of ground rules :

- Establish realistic schedules that would "second guess" failures but provide for exploitation of early success.

- Schedule circumlunar, lunar orbit, and lunar landing missions at the earliest realistic dates.

- Complete the flight development of spacecraft modules and operational techniques, using the Saturn C-1 and C-1B launch vehicles, prior to the time at which a "man-rated" C-5 launch vehicle would become available.

- Develop the spacecraft operational techniques in "buildup" missions that would progress generally from the simple to the complex.

- Use the spacecraft crew at the earliest time and to the maximum extent, commensurate with safety considerations, in the development of the spacecraft and its subsystems.

1962 April 16 - .

- Lunar orbit rendezvous technique - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. Representatives of MSC made a formal presentation at Marshall Space Flight Center on the lunar orbit rendezvous technique for accomplishing the lunar mission..

1962 April 24 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Rosen recommends Saturn C-5 design and lunar orbit rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Rosen, Milton.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

CSM Recovery,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Milton W. Rosen, NASA Office of Manned Space Flight Director of Launch Vehicles and Propulsion, recommended that the S-IVB stage be designed specifically as the third stage of the Saturn C-5 and that the C-5 be designed specifically for the manned lunar landing using the lunar orbit rendezvous technique. The S-IVB stage would inject the spacecraft into a parking orbit and would be restarted in space to place the lunar mission payload into a translunar trajectory. Rosen also recommended that the S- IVB stage be used as a flight test vehicle to exercise the command module (CM), service module (SM), and lunar excursion module (LEM) (previously referred to as the lunar excursion vehicle (LEV)) in earth orbit missions. The Saturn C-1 vehicle, in combination with the CM, SM, LEM, and S-IVB stage, would be used on the most realistic mission simulation possible. This combination would also permit the most nearly complete operational mating of the CM, SM, LEM, and S-IVB prior to actual mission flight.

1962 April 24 - .

- Indecision on the lunar mission mode causing delays in Apollo program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

MSC Associate Director Walter C. William reported to the Manned Space Flight Management Council that the lack of a decision on the lunar mission mode was causing delays in various areas of the Apollo spacecraft program, especially the requirements for the portions of the spacecraft being furnished by NAA.

1962 April - .

- Advantages of lunar orbit rendezvous - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center, writing in the April issue of Astronautics, outlined the advantages of lunar orbit rendezvous for a manned lunar landing as opposed to direct flight from earth or earth orbit rendezvous. Under this concept, an Apollo-type spacecraft would fly directly to the moon, go into lunar orbit, detach a small landing craft which would land on the moon and then return to the mother craft, which would then return to earth. The advantages would be the much smaller craft performing the difficult lunar landing and takeoff, the possibility of optimizing the smaller craft for this one function, the safe return of the mother craft in event of a landing accident, and even the possibility of using two of the small craft to provide a rescue capability.

1962 May 3 - .

- Presentation on the lunar orbit rendezvous technique - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Holmes, Brainard.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

A presentation on the lunar orbit rendezvous technique was made to D. Brainerd Holmes, Director, NASA Office of Manned Space Flight, by representatives of the Apollo Spacecraft Project Office. A similar presentation to NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., followed on May 31.

1962 May 6 - .

- Preliminary Statement of Work for Apollo lunar excursion module - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Source Selection. A preliminary Statement of Work for a proposed lunar excursion module was completed, although the mission mode had not yet been selected..

1962 May 29 - .

- Schedule for contract for development of Apollo lunar excursion module - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

A schedule for the letting of a contract for the development of a lunar excursion module was presented to the Manned Space Flight Management Council by MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth in anticipation of a possible decision to employ the lunar rendezvous technique in the lunar landing mission.

1962 July 1-7 - .

- Delta V requirements for the Apollo lunar landing mission were established - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Guidance, LM Source Selection. The delta V (rate of incremental change in velocity) requirements for the lunar landing mission were established and coordinated with NAA by the Apollo Spacecraft Project Office..

1962 July 10-11 - .

- Report on a simulated lunar landing trainer - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Source Selection. Charles W. Frick, MSC Apollo Project Office Manager, assigned MIT Instrumentation Laboratory to report on a simulated lunar landing trainer using guidance and navigation equipment and other displays as necessary or proposed..

1962 July 25 - .

- Invitation to bid for the Apollo lunar excursion module - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

LM Original Specification,

LM Source Selection.

MSC invited 11 firms to submit research and development proposals for the lunar excursion module (LEM) for the manned lunar landing mission. The firms were Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, The Boeing Airplane Company, Northrop Corporation, Ling-Temco-Vought, Inc., Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, Douglas Aircraft Company, General Dynamics Corporation, Republic Aviation Corporation, Martin- Marietta Company, North American Aviation, Inc., and McDonnell Aircraft Corporation. Additional Details: here....

1962 July 30 - .

- Conclusions on the selection of a lunar mission mode based on studies conducted in 1961 and 1962 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Office of Systems under NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight summarized its conclusions on the selection of a lunar mission mode based on NASA and industry studies conducted in 1961 and 1962:

- There were no significant technical problems which would preclude the acceptance of any of the modes, if sufficient time and money were available. (The modes considered were the C-5 direct ascent, C-5 earth orbit rendezvous (EOR), C-5 lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR), Nova direct ascent, and solid-fuel Nova direct ascent.)

- The C-5 direct ascent technique was characterized by high development risk and the least flexibility for further development.

- The C-5 EOR mode had the lowest probability of mission success and the greatest development complexity.

- The Nova direct ascent method would require the development of larger launch vehicles than the C-5. However, it would be the least complex from an operational and subsystem standpoint and had greater crew safety and initial mission capabilities than did LOR.

- The solid-fuel Nova direct flight mode would necessitate a launch vehicle development parallel to the C-5. Such a development could not be financed under current budget allotments.

- Only the LOR and EOR modes would make full use of the development of the C-5 launch vehicle and the command and service modules. Based on technical considerations, the LOR mode was distinctly preferable.

- The Directors of MSC and Marshall Space Flight Center had both expressed strong preference for the LOR mode.

1962 July - .

- Preliminary design of the Apollo lunar landing radar - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Guidance, LM Source Selection. NAA selected the lunar landing radar and completed the block diagram for the spacecraft rendezvous radar. Preliminary design was in progress on both types of radar..

1962 August 11 - .

- Eight companies to bid on Apollo lunar excursion module - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

Of the 11 companies invited to bid on the lunar excursion module on July 25, eight planned to respond. NAA had notified MSC that it would not bid on the contract. No information had been received from the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation and it was questionable whether the Northrop Corporation would respond.

1962 August 14 - .

- LEM added to Apollo CSM Statement of Work - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Communications,

LM ECS,

LM Guidance,

LM Hatch,

LM Source Selection.

The NAA spacecraft Statement of Work was revised to include the requirements for the lunar excursion module (LEM) as well as other modifications. The LEM requirements were identical with those given in the LEM Development Statement of Work of July 24.

The command module (CM) would now be required to provide the crew with a one-day habitable environment and a survival environment for one week after touching down on land or water. In case of a landing at sea, the CM should be able to recover from any attitude and float upright with egress hatches free of water. Additional Details: here....

1962 September 4 - .

- Nine industry proposals for the Apollo lunar excursion module received - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

Nine industry proposals for the lunar excursion module were received from The Boeing Company, Douglas Aircraft Company, General Dynamics Corporation, Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, Ling-Temco-Vought, Inc., Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, Martin-Marietta Corporation, Northrop Corporation, and Republic Aviation Corporation. NASA evaluation began the next day. Additional Details: here....

1962 September 5 - .

- Study of Apollo docking and crew transfer - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM Hatch,

LM Communications,

LM ECS,

LM Hatch,

LM Source Selection.

Apollo Spacecraft Project Office requested NAA to perform a study of command module-lunar excursion module (CM-LEM) docking and crew transfer operations and recommend a preferred mode, establish docking design criteria, and define the CM-LEM interface. Both translunar and lunar orbital docking maneuvers were to be considered. The docking concept finally selected would satisfy the requirements of minimum weight, design and functional simplicity, maximum docking reliability, minimum docking time, and maximum visibility.

The mission constraints to be used for this study were :

- The first docking maneuver would take place as soon after S-IVB burnout as possible and hard docking would be within 30 minutes after burnout.

- The docking methods to be investigated would include but not be limited to free fly-around, tethered fly-around, and mechanical repositioning.

- The S-IVB would be stabilized for four hours after injection.

- There would be no CM airlock. Extravehicular access techniques through the LEM would be evaluated to determine the usefulness of a LEM airlock.

- A crewman would not be stationed in the tunnel during docking unless it could be shown that his field of vision, maneuverability, and communication capability would substantially contribute to the ease and reliability of the docking maneuver.

- An open-hatch, unpressurized CM docking approach would not be considered.

- The relative merit of using the CM environmental control system to provide initial pressurization of the LEM instead of the LEM environmental control system would be investigated.

1962 September 5 - .

- Studies of Apollo unmanned logistic system - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo ULS.

Two three-month studies of an unmanned logistic system to aid astronauts on a lunar landing mission would be negotiated with three companies, NASA announced. Under a $150,000 contract, Space Technology Laboratories, Inc., would look into the feasibility of developing a general-purpose spacecraft into which varieties of payloads could be fitted. Under two $75,000 contracts, Northrop Space laboratories and Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation would study the possible cargoes that such a spacecraft might carry. NASA Centers simultaneously would study lunar logistic: trajectories, launch vehicle adaptation, lunar landing touchdown dynamics, scheduling, and use of roving vehicles on the lunar surface.

1962 September 21 - .

- Contract with Armour Research Foundation for investigation of conditions on the lunar surface - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Landing Gear,

LM Source Selection.

NASA contracted with the Armour Research Foundation for an investigation of conditions likely to be found on the lunar surface. Research would concentrate first on evaluating the effects of landing velocity, size of the landing area, and shape of the landing object with regard to properties of the lunar soils. Earlier studies by Armour had indicated that the lunar surface might be composed of very strong material. Amour reported its findings during the first week of November.

1962 September - .

- Apollo lunar excursion module systems - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

The lunar excursion module was defined as consisting of 12 principal systems: guidance and navigation, stabilization and control, propulsion, reaction control, lunar touchdown, structure including landing and docking systems, crew, environmental control, electrical power, communications, instrumentation, and experimental instrumentation. A consideration of prime importance to practically all systems was the possibility of using components from Project Mercury or those under development for Project Gemini.

1962 October 24 - .

- Final manned lunar landing mode report - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Kennedy,

Wiesner.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

Faced by opposition of mode selection by Jerome Wiesner, Kennedy's science adviser, NASA let contracts to McDonnell and STL for direct two-man flight modes. Both concluded that it was feasible but would require LH2/LOX stages for descent and ascent from lunar surface, which NASA/STG adamantly opposed. This was also the last stab - for the time being - at 'lunar Gemini'.

The Office of Systems under NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight completed a manned lunar landing mode comparison embodying the most recent studies by contractors and NASA Centers. The report was the outgrowth of the decision announced by NASA on July 11 to continue studies on lunar landing modes while basing planning and procurement primarily on the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) technique. Additional Details: here....

1962 First Week - .

- Lunar surface might not be covered with dust layers - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM ECS,

LM Source Selection.

The Amour Research Foundation reported to NASA that the surface of the moon might not be covered with layers of dust. The first Armour studies showed that dust particles become harder and denser in a higher vacuum environment such as that of the moon, but the studies had not proved that particles eventually become bonded together in a rocket substance as the vacuum increases.

1962 November 7 - .

- Selection of Grumman to build the Apollo lunar excursion module - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Webb.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

LM Source Selection.

NASA announced that the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation had been selected to build the lunar excursion module of the three-man Apollo spacecraft under the direction of MSC. The contract, still to be negotiated, was expected to be worth about $350 million, with estimates as high as $1 billion by the time the project would be completed. Additional Details: here....

1962 November 19 - .

- Negotiations on the lunar excursion module (Apollo LEM) contract begin - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Source Selection.

About 100 Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation and MSC representatives began seven weeks of negotiations on the lunar excursion module (LEM) contract. After agreeing on the scope of work and on operating and coordination procedures, the two sides reached fiscal accord. Negotiations were completed on January 3, 1963. Eleven days later, NASA authorized Grumman to proceed with LEM development.

1962 November 26 - .

- Inflight practice at orbital maneuvering said to be essential for lunar missions - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Guidance.

At a news conference in Cleveland, Ohio, during the 10-day Space Science Fair there, NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden stated that inflight practice at orbital maneuvering was essential for lunar missions. He believed that landings would follow reconnaissance of the moon by circumlunar and near- lunar-surface flights.

1962 November - .

- Study of Apollo CSM-LEM transposition and docking - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM RCS,

LM RCS,

LM Weight.

North American completed a study of CSM-LEM transposition and docking. During a lunar mission, after the spacecraft was fired into a trajectory toward the moon, the CSM would separate from the adapter section containing the LEM. It would then turn around, dock with the LEM, and pull the second vehicle free from the adapter. The contractor studied three methods of completing this maneuver: free fly-around, tethered fly- around, and mechanical repositioning. Of the three, the company recommended the free fly-around, based on NASA's criteria of minimum weight, simplicity of design, maximum docking reliability, minimum time of operation, and maximum visibility.

Also investigated was crew transfer from the CM to the LEM, to determine the requirements for crew performance and, from this, to define human engineering needs. North American concluded that a separate LEM airlock was not needed but that the CSM oxygen supply system's capacity should be increased to effect LEM pressurization.

On November 29, North American presented the results of docking simulations, which showed that the free flight docking mode was feasible and that the 45-kilogram (100-pound) service module (SM) reaction control system engines were adequate for the terminal phase of docking. The simulations also showed that overall performance of the maneuver was improved by providing the astronaut with an attitude display and some form of alignment aid, such as probe.

1962 December 10 - .

- Selection of lunar orbit rendezvous for Apollo explained to Kennedy - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Webb.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

LM Mode Debate.

NASA Administrator James E. Webb, in a letter to the President, explained the rationale behind the Agency's selection of lunar orbit rendezvous (rather than either direct ascent or earth orbit rendezvous) as the mode for landing Apollo astronauts on the moon. Arguments for and against any of the three modes could have been interminable: "We are dealing with a matter that cannot be conclusively proved before the fact," Webb said. "The decision on the mode . . . had to be made at this time in order to maintain our schedules, which aim at a landing attempt in late 1967."

1962 December 11 - .

- Apollo LEM docking study authorized - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Crew Station. NASA authorized North American's Columbus, Ohio, Division to proceed with a LEM docking study..

1962 December 20 - .

- Apollo LEM's descent engine might create a dust storm on the lunar surface - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Descent Propulsion. MSC prognosticated that, during landing, exhaust from the LEM's descent engine would kick up dust on the moon's surface, creating a dust storm. Landings should be made where surface dust would be thinnest..

1962 - During the last quarter - .

- Grumman agreed to use existing Apollo components and subsystems in the LEM - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM. Grumman agreed to use existing Apollo components and subsystems, where practicable, in the LEM This promised to simplify checkout and maintenance of spacecraft systems..

1962 December - .

- Project Apollo lunar landing mission design - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM. MSC prepared the Project Apollo lunar landing mission design. This plan outlined ground rules, trajectory analyses, sequences of events, crew activities, and contingency operations. It also predicted possible planning changes in later Apollo flights..

1963 January 16 - .

- Three Apollo operational procedures for the first phase of descent from lunar orbit analyzed - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Guidance.

The MSC Flight Operations Division's Mission Analysis Branch analyzed three operational procedures for the first phase of descent from lunar orbit:

- The first was a LEM-only maneuver. The LEM would transfer to an orbit different from that of the CSM but with the same period and having a pericynthion of 15,240 meters (50,000 feet). After one orbit and reconnaissance of the landing site, the LEM would begin descent maneuvers.

- The second method required the entire spacecraft (CSM/LEM) to transfer from the initial circular orbit to an elliptical orbit with a pericynthion of 15,240 meters (50,000 feet).

- The third technique involved the LEM's changing from the original 147-kilometer (80-nautical-mile) circular orbit to an elliptic orbit having a pericynthion of 15,240 meters (50,000 feet). The CSM, in turn, would transfer to an elliptic orbit with a pericynthion of 65 kilometers (30 nautical miles). This would enable the CSM to keep the LEM under observation until the LEM began its descent to the lunar surface.

(Apocynthion and pericynthion are the high and low points, respectively, of an object in orbit around the moon (as, for example, a spacecraft sent from earth). Apolune and perilune also refer to these orbital parameters, but these latter two words apply specifically to an object launched from the moon itself.)

1963 January 18 - .

- Contract to Bell for two Apollo lunar landing research vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

NASA's Flight Research Center (FRC) announced the award of a $3.61 million contract to Bell Aerosystems Company of Bell Aerospace Corporation for the design and construction of two manned lunar landing research vehicles. The vehicles would be able to take off and land under their own power, reach an altitude of about 1,220 meters (4,000 feet), hover, and fly horizontally. A fan turbojet engine would supply a constant upward push of five-sixths the weight of the vehicle to simulate the one-sixth gravity of the lunar surface. Tests would be conducted at FRC.

1963 January 28 - .

- Conference on the Apollo LEM electrical power system (EPS) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Electrical.

Following a technical conference on the LEM electrical power system (EPS), Grumman began a study to define the EPS configuration. Included was an analysis of EPS requirements and of weight and reliability for fuel cells and batteries. Total energy required for the LEM mission, including the translunar phase, was estimated at 61.3 kilowatt-hours. Upon completion of this and a similar study by MSC, Grumman decided upon a three-cell arrangement with an auxiliary battery. Capacity would be determined when the EPS load analysis was completed.

1963 January 30 - .

- Selection of four companies as major Apollo LEM subcontractors - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Ascent Propulsion,

LM Descent Propulsion,

LM ECS,

LM RCS.

Grumman and NASA announced the selection of four companies as major LEM subcontractors:

- Rocketdyne for the descent engine

- Bell Aerosystems Company for the ascent engine

- The Marquardt Corporation for the reaction control system

- Hamilton Standard for the environmental control system

1963 January - .

- Contract to Chance Vought for study of guidance of the Apollo LEM in a lunar landing abort - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Guidance. MSC awarded a contract to Chance Vought Corporation for a study of guidance system techniques for the LEM in an abort during lunar landing..

1963 February - .

- LLRV contract - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

After conceptual planning and meetings with engineers from Bell Aerosystems, Buffalo, NY, a company with experience in vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft, NASA issued Bell a $50,000 study contract in December 1961. Bell had independently conceived a similar, free-flying simulator, and out of this study came the NASA Headquarters' endorsement of the LLRV concept, resulting in a $3.6 million production contract awarded to Bell for delivery of the first of two vehicles for flight studies at the FRC within 14 months.

1963 February 13 - .

- Reorganization of Apollo SPO - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Caldwell,

Maynard.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM Guidance.

In a reorganization of ASPO, MSC announced the appointment of two deputy managers. Robert O. Piland, deputy for the LEM, and James L. Decker, deputy for the CSM, would supervise cost, schedule, technical design, and production. J. Thomas Markley was named Special Assistant to the Apollo Manager, Charles W. Frick. Also appointed to newly created positions were Caldwell C. Johnson, Manager, Spacecraft Systems Office, CSM; Owen E. Maynard, Acting Manager, Spacecraft Systems Office, LEM; and David W. Gilbert, Manager, Spacecraft Systems Office, Guidance and Navigation.

1963 February 13 - .

- Discussions with Rocketdyne on a throttleable Apollo LEM descent engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Descent Propulsion. Grumman began discussions with Rocketdyne on the development of a throttleable LEM descent engine. Engine specifications (helium injected, 10:1 thrust variation) had been laid down by MSC..

1963 February 24-March 23 - .

- Lunar Surface Experiments Panel - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo ALSEP. The MSC Lunar Surface Experiments Panel held its first meeting. This group was formed to study and evaluate lunar surface experiments and the adaptability of Surveyor and other unmanned probes for use with manned missions..

1963 February 25 - .

- Talks with Bell on development of the Apollo LEM ascent engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Ascent Propulsion. Grumman began initial talks with the Bell Aerosystems Company on development of the LEM ascent engine. Complete specifications were expected by March 2..

1963 February 26 - .

- Orbital constraints on Apollo CSM - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM Docking,

LM Guidance.

Two aerospace technologists at MSC, James A. Ferrando and Edgar C. Lineberry, Jr., analyzed orbital constraints on the CSM imposed by the abort capability of the LEM during the descent and hover phases of a lunar mission. Their study concerned the feasibility of rendezvous should an emergency demand an immediate return to the CSM.

Ferrando and Lineberry found that, once abort factors are considered, there exist "very few" orbits that are acceptable from which to begin the descent. They reported that the most advantageous orbit for the CSM would be a 147-kilometer (80-nautical-mile) circular one.

1963 February 27 - .

- Alternate Apollo LEM descent propulsion system - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Descent Propulsion.

Aviation Daily reported an announcement by Frank Canning, Assistant LEM Project Manager at Grumman, that a Request for Proposals would be issued in about two weeks for the development of an alternate descent propulsion system. Because the descent stage presented what he called the LEM's "biggest development problem," Canning said that the parallel program was essential.

1963 February 27 - .

- Apollo Mission Planning Panel - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

The Apollo Mission Planning Panel held its organizational meeting at MSC. The panel's function was to develop the lunar landing mission design, coordinate trajectory analyses for all Saturn missions, and develop contingency plans for all manned Apollo missions.

Membership on the panel included representatives from MSC, MSFC, NASA Headquarters, North American, Grumman, and MIT, with other NASA Centers being called on when necessary. By outlining the most accurate mission plan possible, the panel would ensure that the spacecraft could satisfy Apollo's anticipated mission objectives. Most of the panel's influence on spacecraft design would relate to the LEM, which was at an earlier stage of development than the CSM. The panel was not given responsibility for preparing operational plans to be used on actual Apollo missions, however.

1963 February - .

- One-tenth scale model of the Apollo LEM for stage separation tests - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Ascent Propulsion,

LM Landing Gear.

Grumman began fabrication of a one-tenth scale model of the LEM for stage separation tests. In launching from the lunar surface, the LEM's ascent engine fires just after pyrotechnic severance of all connections between the two stages, a maneuver aptly called "fire in the hole."

Also, Grumman advised that, from the standpoint of landing stability, a five-legged LEM was unsatisfactory. Under investigation were a number of landing gear configurations, including retractable legs.

1963 March 4 - .

- Discussions with Hamilton Standard on Apollo LEM environmental control system - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM ECS. Grumman began initial discussions with Hamilton Standard on the development of the LEM environmental control system..

1963 March 7 - .

- Report on power sources for the Apollo LEM - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Electrical.

Grumman representatives presented their technical study report on power sources for the LEM. They recommended three fuel cells in the descent stage (one cell to meet emergency requirements), two sets of fluid tanks, and two batteries for peak power loads. For industrial competition to develop the power sources, Grumman suggested Pratt and Whitney Aircraft and GE for the fuel cells, and Eagle-Picher, Electrical Storage Battery, Yardney, Gulton, and Delco-Remy for the batteries.

1963 March 10 - .

- Grumman presented its first monthly progress report on the Apollo LEM - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

Grumman presented its first monthly progress report on the LEM. In accordance with NASA's list of high-priority items, principal engineering work was concentrated on spacecraft and subsystem configuration studies, mission plans and test program investigations, common usage equipment surveys, and preparation for implementing subcontractor efforts.

1963 March 11 - .

- First Apollo LM fire-in-the-hole model test - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Ascent Propulsion. Grumman completed its first "fire-in-the-hole" model test. Even though preliminary data agreed with predicted values, they nonetheless planned to have a support contractor, the Martin Company, verify the findings..

1963 March 11 - .

- Definitive contract formalized for the Apollo Lunar Excursion Module - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

NASA announced signing of the contract with Grumman for development of the LEM. Company officials had signed the document on January 21 and, following legal reviews, NASA Headquarters had formally approved the agreement on March 7. Under the fixed-fee contract (NAS 9-1100) ($362.5 million for costs and $25.4 million in fees) Grumman was authorized to design, fabricate, and deliver nine ground test and 11 flight vehicles. The contractor would also provide mission support for Apollo flights. MSC outlined a developmental approach, incorporated into the contract as "Exhibit B, Technical Approach," that became the "framework within which the initial design and operational modes" of the LEM were developed.

1963 March 11 - .

- Contract talks with Marquardt for Apollo LEM reaction control system - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM RCS. Grumman began early contract talks with the Marquardt Corporation for development of the LEM reaction control system..

1963 March 14 - .

- Bidders' conference for Apollo LEM mechanically throttled descent engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Descent Propulsion,

LM RCS.

A bidders' conference was held at Grumman for a LEM mechanically throttled descent engine to be developed concurrently with Rocketdyne's helium injection descent engine. Corporations represented were Space Technology Laboratories; United Technology Center, a division of United Aircraft Corporation; Reaction Motors Division, Thiokol Chemical Corporation; and Aerojet-General Corporation. Technical and cost proposals were due at Grumman on April 8.

1963 March 27 - .

- Firm requirements for the lunar landing mission - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

The Apollo Mission Planning Panel set forth two firm requirements for the lunar landing mission. First, both LEM crewmen must be able to function on the lunar surface simultaneously. MSC contractors were directed to embody this requirement in the design and development of the Apollo spacecraft systems. Second, the panel established duration limits for lunar operations. These limits, based upon the 48-hour LEM operation requirement, were 24 hours on the lunar surface and 24 hours in flight on one extreme, and 45 surface hours and 3 flight hours on the other. Grumman was directed to design the LEM to perform throughout this range of mission profiles.

1963 - During the second quarter - .

- Stowage of crew equipment in both the Apollo CM and LEM worked out - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: A7L,

Apollo LM,

CSM Cockpit,

LM Structural.

MSC reported that stowage of crew equipment, some of which would be used in both the CM and the LEM, had been worked out. Two portable life support systems and three pressure suits and thermal garments were to be stowed in the CM. Smaller equipment and consumables would be distributed between modules according to mission phase requirements.

1963 - During the second quarter - .

- Preliminary plans for Apollo scientific instrumentation - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo ALSEP.

MSC reported that preliminary plans for Apollo scientific instrumentation had been prepared with the cooperation of NASA Headquarters, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Goddard Space Flight Center. The first experiments would not be selected until about December 1963, allowing scientists time to prepare proposals. Prime consideration would be given to experiments that promised the maximum return for the least weight and complexity, and to those that were man-oriented and compatible with spacecraft restraints. Among those already suggested were seismic devices (active and passive), and instruments to measure the surface bearing strength, magnetic field, radiation spectrum, soil density, and gravitational field. MSC planned to procure most of this equipment through the scientific community and through other NASA and government organizations.

1963 March - .

- MSC sent MIT and Grumman radar configuration requirements for the Apollo LEM - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM Guidance,

LM Guidance.

MSC sent MIT and Grumman radar configuration requirements for the LEM. The descent equipment would be a three-beam doppler radar with a two-position antenna. Operating independently of the primary guidance and navigation system, it would determine altitude, rate of descent, and horizontal velocity from 7,000 meters (20,000 feet) above the lunar surface. The LEM rendezvous radar, a gimbaled antenna with a two-axis freedom of movement, and the rendezvous transponder mounted on the antenna would provide tracking data, thus aiding the LEM to intercept the orbiting CM. The SM would be equipped with an identical rendezvous radar and transponder.

1963 March - .

- Study on ablative versus regenerative cooling for the Apollo LEM ascent engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Ascent Propulsion.

RCA completed a study on ablative versus regenerative cooling for the thrust chamber of the LEM ascent engine. Because of low cooling margins available with regenerative cooling, Grumman selected the ablative method, which permitted the use of either ablation or radiation cooling for the nozzle extension.

1963 March - .

- Preliminary design specifications for the Apollo LEM communications system - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Communications.

Grumman met with representatives of North American, Collins Radio Company, and Motorola, Inc., to discuss common usage and preliminary design specifications for the LEM communications system. These discussions led to a simpler design for the S-band receiver and to modifications to the S-band transmitter (required because of North American's design approach).

1963 April 1 - .

- Grumman began Lunar Hover and Landing Simulation IIIA tests - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Simulator.

Grumman began "Lunar Hover and Landing Simulation IIIA," a series of tests simulating a LEM landing. Crew station configuration and instrument panel layout were representative of the actual vehicle.

Through this simulation, Grumman sought primarily to evaluate the astronauts' ability to perform the landing maneuver manually, using semiautomatic as well as degraded attitude control modes. Other items evaluated included the flight control system parameters, the attitude and thrust controller configurations, the pressure suit's constraint during landing maneuvers, the handling qualities and operation of LEM test article 9 as a freeflight vehicle, and manual abort initiation during the terminal landing maneuver.

1963 April 17 - .

- Preliminary configuration freeze for the Apollo LEM - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Landing Gear.

At a mechanical systems meeting at MSC, customer and contractor achieved a preliminary configuration freeze for the LEM. Several features of the design of the two stages were agreed upon:

- Descent

- four cylindrical propellant tanks (two oxidizer and two fuel); four- legged deployable landing gear

- Ascent

- a cylindrical crew cabin (about 234 centimeters (92 inches) in diameter) and a cylindrical tunnel (pressurized) for equipment stowage; an external equipment bay.

1963 April - .

- Apollo LEM reaction control system (RCS) to be equipped with dual interconnected tanks - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM RCS.

Grumman recommended that the LEM reaction control system (RCS) be equipped with dual interconnected tanks, separately pressurized and employing positive expulsion bladders. The design would provide for an emergency supply of propellants from the main ascent propulsion tanks. The RCS oxidizer to fuel ratio would be changed from 2.0:1 to 1.6:1. MSC approved both of these changes.

1963 April - .

- Grumman studies on common usage of Apollo CSM/LM communications - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, CSM Television, LM Communications, LM Television. Grumman reported to MSC the results of studies on common usage of communications. Television cameras for the two spacecraft would be identical; the LEM transponder would be as similar as possible to that in the CSM..

1963 May 1 - .

- Rocketdyne gvien go ahead for Apollo LEM descent engine - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Descent Propulsion.

Grumman reported that it had advised North American's Rocketdyne Division to go ahead with the lunar excursion module descent engine development program. Negotiations were complete and the contract was being prepared for MSC's review and approval. The go-ahead was formally issued on May 2.

1963 May 2 - .

- CM television camera made compatible with that in the Apollo LEM - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM Television,

LM Television.

NASA, North American, Grumman, and RCA representatives determined the alterations needed to make the CM television camera compatible with that in the LEM: an additional oscillator to provide synchronization, conversion of operating voltage from 115 AC to 28 DC, and reduction of the lines per frame from 400 to 320.

1963 May 6 - .

- Apollo LEM manual control simulated - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Armstrong,

Carpenter,

Conrad,

McDivitt,

Schirra,

See,

White,

Young.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM Guidance,

LM Simulator.

Astronauts M. Scott Carpenter, Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Neil A. Armstrong, James A. McDivitt, Elliot M. See, Jr., Edward H. White II, Charles Conrad, Jr., and John W. Young participated in a study in LTV's Manned Space Flight Simulator at Dallas, Tex. Under an MSC contract, LTV was studying the astronauts' ability to control the LEM manually and to rendezvous with the CM if the primary guidance system failed during descent.

1963 May 7 - .

- Reorganization of Apollo SPO - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Caldwell.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

MSC announced a reorganization of ASPO:

- Acting Manager:

- Robert O. Piland

- Deputy Manager, Spacecraft:

- Robert O. Piland

- Assistant Deputy Manager for CSM:

- Caldwell C. Johnson

- Deputy Manager for System Integration:

- Alfred D. Mardel

- Deputy Manager LEM:

- James L. Decker

- Manager, Spacecraft Systems Office:

- David W. Gilbert

- Manager, Project Integration Office:

- J. Thomas Markley

1963 May 10 - .

- The first meeting of the Apollo LEM Flight Technology Systems Panel was held at MSC - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM ECS,

LM Weight.

The first meeting of the LEM Flight Technology Systems Panel was held at MSC. The panel was formed to coordinate discussions on all problems involving weight control, engineering simulation, and environment. The meeting was devoted to a review of the status of LEM engineering programs.

1963 Early in the Month - .

- STL to build the mechanically throttled descent engine for the Apollo LEM - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM, LM Descent Propulsion. Grumman selected Space Technology Laboratories (STL) to develop and fabricate a mechanically throttled descent engine for the LEM, paralleling Rocketdyne's effort. Following NASA and MSC concurrence, Grumman began negotiations with STL on June 1..

1963 May 14 - .

- Quality Control Program Plan for the Apollo LEM - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LM. Grumman submitted to NASA a Quality Control Program Plan for the LEM, detailing efforts in management, documentation, training, procurement, and fabrication..

1963 May 15 - .

- LLRV could be used to test Apollo LEM hardware - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Grumman, reporting on the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle's (LLRV) application to the LEM development program, stated the LLRV could be used profitably to test LEM hardware. Also included was a development schedule indicating the availability of LEM equipment and the desired testing period.

1963 May 20-22 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn V.

- Status report on the Apollo LEM landing gear design and Apollo LEM stowage height - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

LM Landing Gear.

At a meeting on mechanical systems at MSC, Grumman presented a status report on the LEM landing gear design and LEM stowage height. On May 9, NASA had directed the contractor to consider a more favorable lunar surface than that described in the original Statement of Work. Additional Details: here....

1963 May 22 - .

- Grumman representatives met with the Apollo ASPO Electrical Systems Panel (ESP) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: A7L,

Apollo LM,

CSM Communications,

LM Communications.

Grumman representatives met with the ASPO Electrical Systems Panel (ESP). From ESP, the contractor learned that the communications link would handle voice only. Transmission of physiological and space suit data from the LEM to the CM was no longer required. VHF reception of this data and S-band transmission to ground stations was still necessary. In addition, Grumman was asked to study the feasibility of a backup voice transmitter for communications with crewmen on the lunar surface should the main VHF transmitter fail.

1963 May 23 - .

- Apollo LEM and CSM to incorporate phase-coherent S-band transponders - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM,

CSM SPS,

LM Communications.