Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Apollo LLRV

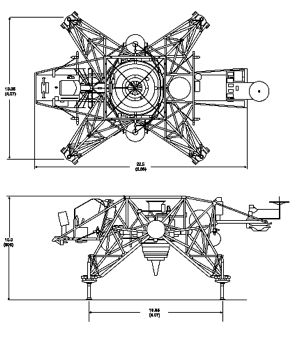

Apollo LLRV Credit: NASA |

AKA: Apollo LLTV;Lunar Lander Test Vehicle;Lunar Landing Research Vehicle. Status: Operational 1965.

A follow-on contract for three 'production' versions for astronaut training were referred to as LLTV 'lunar landing training vehicles'.

The LLRV could take off and land under its own power, reaching an altitude of about 1,220 meters, hover, and fly horizontally. A fan turbojet engine provided a constant upward push of five-sixths the weight of the vehicle to simulate the one-sixth gravity of the lunar surface.

The LLRV's, humorously referred to as "flying bedsteads," were created by a predecessor of NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center to study and analyze piloting techniques needed to fly and land the tiny Apollo Lunar Module in the moon's airless environment. (Dryden was known as NASA's Flight Research Center from 1959 to 1976.)

Success of the LLRV's led to the building of three Lunar Landing Training Vehicles (LLTV's) used by Apollo astronauts at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, TX, predecessor of NASA's Johnson Space Center.

Apollo 11 astronaut, Neil Armstrong first human to step onto the moon's surface said the mission would not have been successful without the type of simulation that resulted from the LLRV's and LLTV's.

Background

When Apollo planning was underway in 1960, NASA was looking for a simulator to profile the descent to the moon's surface. Three concepts were developed: an electronic simulator, a tethered device, and the ambitious Flight Research Center (FRC) contribution, a free-flying vehicle. All three became serious projects, but eventually the FRC's LLRV became the most significant one. Hubert Drake was credited with originating the idea, while Donald Bellman and Gene Matranga were senior engineers on the project, with Bellman the project manager.

After conceptual planning and meetings with engineers from Bell Aerosystems, Buffalo, NY, a company with experience in vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft, NASA issued Bell a $50,000 study contract in December 1961. Bell had independently conceived a similar, free-flying simulator, and out of this study came the NASA Headquarters' endorsement of the LLRV concept, resulting in a $3.6 million production contract awarded to Bell Feb. 1, 1963, for delivery of the first of two vehicles for flight studies at the FRC within 14 months.

Built of aluminum alloy trusses and shaped like a giant four-legged bedstead, the vehicle was to simulate a lunar landing profile. To do this, the LLRV had a General Electric CF-700-2V turbofan engine mounted vertically in a gimbal, with 4200 lb of thrust. The engine got the vehicle up to the test altitude and was then throttled back to support five-sixths of the vehicle's weight, simulating the reduced gravity of the moon. Two hydrogen peroxide lift rockets with thrust that could be varied from 100 to 500 lb handled the LLRV's rate of descent and horizontal movement. Sixteen smaller hydrogen peroxide rockets, mounted in pairs, gave the pilot control in pitch, yaw, and roll. As safety backups on the LLRV, six 500-lb rockets could take over the lift function and stabilize the craft for a moment if the main jet engine failed. The pilot had a zero-zero ejection seat that would then lift him away to safety.

Flight Operations

The two LLRV's were shipped from Bell to the FRC in Apr. 1964, with program emphasis on vehicle No. 1. It was first readied for captured flight on a tilt table constructed at the FRC to test the engines without actually flying. The scene then shifted to the old South Base area of Edwards. On the day of the first flight, Oct. 30, 1964, research pilot Joe Walker flew it three times for a total of just under 60 seconds to a peak altitude of ten ft (3 m). Later flights were shared between Walker; another Center pilot, Don Mallick; the Army's Jack Kleuver; and NASA Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, pilots Joseph Algranti and H.E. "Bud" Ream.

NASA had accumulated enough data from the LLRV flight program at the FRC by mid-1966 to give Bell a contract to deliver three LLTV's at a cost of $2.5 million each.

In Dec. 1966 vehicle No. 1 was shipped to Houston, followed by No. 2 in Jan. 1967, within weeks of its first flight. Modifications already made to No. 2 had given the pilot a three-axis side control stick and a more restrictive cockpit view, both features of the real Lunar Module that would later be flown by the astronauts down to the moon's surface.

When the LLRV's arrived at Houston, where research pilots would learn how to become LLTV instructor pilots, No. 2 had been flown just 7 times while No. 1, the veteran, had a total of 198 flights. In Dec. 1967, the first of the LLTV's joined the FRC's LLRV's to eventually make up the five-vehicle training and simulator fleet.

Three of the five vehicles were later destroyed in crashes at Houston - LLRV No. 1 in May 1968 and two LLTV's, in Dec. 1968 and Jan. 1971.

The two accidents in 1968, before the first lunar landing, did not deter Apollo program managers who enthusiastically relied on the vehicles for simulation and training.

Donald "Deke" Slayton, then NASA's astronaut chief, said there was no other way to simulate a moon landing except by flying the LLTV.

LLRV No. 2 was eventually returned to Dryden, where it was on display as a silent artifact of the Center's contribution to the Apollo program.

Family: Lunar lander test vehicle, Moon. Country: USA. Agency: Bell. Bibliography: 16, 2443, 2479, 2480, 2481, 2482, 2483, 2486, 376, 4436, 459.

| Apollo LLRV 2 View Credit: NASA |

1963 January 18 - .

- Contract to Bell for two Apollo lunar landing research vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

NASA's Flight Research Center (FRC) announced the award of a $3.61 million contract to Bell Aerosystems Company of Bell Aerospace Corporation for the design and construction of two manned lunar landing research vehicles. The vehicles would be able to take off and land under their own power, reach an altitude of about 1,220 meters (4,000 feet), hover, and fly horizontally. A fan turbojet engine would supply a constant upward push of five-sixths the weight of the vehicle to simulate the one-sixth gravity of the lunar surface. Tests would be conducted at FRC.

1963 February - .

- LLRV contract - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

After conceptual planning and meetings with engineers from Bell Aerosystems, Buffalo, NY, a company with experience in vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft, NASA issued Bell a $50,000 study contract in December 1961. Bell had independently conceived a similar, free-flying simulator, and out of this study came the NASA Headquarters' endorsement of the LLRV concept, resulting in a $3.6 million production contract awarded to Bell for delivery of the first of two vehicles for flight studies at the FRC within 14 months.

1963 May 15 - .

- LLRV could be used to test Apollo LEM hardware - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Grumman, reporting on the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle's (LLRV) application to the LEM development program, stated the LLRV could be used profitably to test LEM hardware. Also included was a development schedule indicating the availability of LEM equipment and the desired testing period.

1964 April - .

- LLRV's shipped to NASA - . Nation: USA. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV. The two LLRV's were shipped from Bell to the NASA FRC, with program emphasis on vehicle No. 1. It was first readied for captured flight on a tilt table constructed at the FRC to test the engines without actually flying..

1964 April 7 - .

- First of two Apollo lunar landing research vehicles completed - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV. Bell Aerosystems Company completed the first of two lunar landing research vehicles, to be delivered to the NASA Flight Research Center for testing..

1964 October 30 - .

- LLRV first flight - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Initial tests were from the old South Base area of Edwards. Research pilot Joe Walker flew it three times for a total of just under 60 seconds to a peak altitude of ten ft (3 m). Later flights were shared between Walker; another Center pilot, Don Mallick; the Army's Jack Kleuver; and NASA Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, pilots Joseph Algranti and H.E. 'Bud' Ream.

1964 November 16 - .

- Apollo LLRV first successful flight - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

NASA test pilot Joseph A. Walker flew the LLRV for the second time. The first attempted liftoff, into a 9.26-km (5-nm) breeze, was stopped because of excessive drift to the rear. The vehicle was then turned to head downwind and liftoff was accomplished. While airborne the LLRV drifted with the wind and descent to touchdown was accomplished. Touchdown and resulting rollout (at that time the vehicle was on casters) took the LLRV over an iron-door-covered pit. One door blew off but did not strike the vehicle.

1964 November - .

- Six flights of the Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Six flights of the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) were made during the month, bringing the total number to seven. The project pilot, Joseph Walker, made all flights and demonstrated a rapid increase in the ease and skill with which he handled the craft as the flights progressed.

Altitudes to between 18 and 21 m (60 and 70 ft) and flight duration up to three minutes were attained. Additional Details: here....

1965 January 26 - .

- Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle results - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Warren J. North, Chairman of the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) Coordination Panel, reported to MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth that the LLRV had been flown 10 times by Flight Research Center pilots - eight times by Joe Walker and twice by Don Mallick. Maximum altitude achieved was 91 m (300 ft) and maximum forward velocity was 12 m (40 ft) per sec. Additional Details: here....

1965 March 9 - .

- Initial flights of the LLRV - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV,

LM Descent Propulsion,

LM Guidance.

Initial flights of the LLRV interested MSC's Guidance and Control Division because they represented first flight tests of a vehicle with control characteristics similar to the LEM. The Division recommended the following specific items for inclusion in the LLRV flight test program:

- The handling qualities of the LEM attitude control system should be verified using the control powers available to the pilot during the landing maneuver. The attitude controller used in these tests should be a three-axis LEM rotational controller.

- The ability of pilots to manually zero the horizontal velocities at altitudes of 30.48 m (100 ft) or less should be investigated. The view afforded the pilot during this procedure should be equivalent to the view available to the pilot in the actual LEM.

- The LEM descent engine throttle control should be investigated to determine proper relationship between control and thrust output for the landing maneuver.

- Data related to attitude and attitude rates encountered in landing approach maneuvers were desirable to verify LEM control system design limits.

- Adequacy of LEM flight instrument displays used for the landing maneuver should be determined.

1965 March 19 - .

- Bell study to significantly increase simulation time for Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Bell Aerosystems Company reported that a study had been made to determine if it were practical to significantly increase simulation time without major changes to the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV). This study had been made after MSC personnel had expressed an interest in increased simulation time for a trainer version of the LLRV. The current LLRV was capable of about 10 minutes of flight time and two minutes of lunar simulation with the lift rockets providing one-sixth of the lift. It was concluded that lunar simulation time approaching seven minutes could be obtained by doubling the 272-kg (600-lb) peroxide load and employing the jet engine to simulate one-half of the rocket lift needed for simulation.

A major limiting factor, however, was the normal weather conditions at Houston, where such a training vehicle would be located. A study showed that in order to use a maximum peroxide load of 544 kg (1,200 lbs), the temperature could not exceed 313K (40 degrees F); and at 332K (59 degrees F) the maximum load must be limited to 465 kg (1,025 lbs) of peroxide. On the basis of existing weather records it was determined there would be enough days on which flights could be made in Houston on the basis of 544 kg (1,200 lbs) peroxide at 313K (40 degrees F), 465 kg (1,025 lbs) at 332K (59 degrees F), and 354 kg (775 lbs) at 353K (80 degrees F) to make provisions for such loads.

1965 March - .

- Three flights with the Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Three flights were made with the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) for the purpose of checking the automatic systems that control the attitude of the jet engine and adjusting the throttle so the jet engine would support five-sixths of the vehicle weight.

On March 11 representatives of Flight Research Center (FRC) visited MSC to discuss future programs with Warren North and Dean Grimm of Flight Crew Support Division. A budget for operating the LLRV at FRC through fiscal year 1966 was presented. Consideration was being given to terminating the work at FRC on June 30, 1966, and moving the vehicles and equipment to MSC. Additional Details: here....

1965 April 22-29 - .

- Data from the Bell Apollo LEM training vehicle more than a year away - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV, Apollo LM. After reviewing the status of the LEM landing simulation program, the Guidance and Control Division reported that "significant data" from the Bell training vehicle were more than a year away..

1965 May - .

- Three flights made with Apollo LLRV - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Three flights were made with the lunar landing research vehicle (LLRV) by FRC pilot Don Mallick for the purpose of checking the initial weighing, the thrust-to-weight, and the automatic throttle systems.

General Electric would update the LLRV CF-700 jet engines at their Edwards AFB facility rather than at Lynn, Mass. The change in work location would mean an earlier delivery date and a significant cost reduction. The updating would make the engines comparable to the production engines and would add an additional 890 newtons (200 lbs) of thrust.

1965 June 2 - .

- Reduced preflight time for the Apollo lunar landing research vehicle (LLRV) - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

In an attempt to reduce the overall preflight time in connection with lunar landing research vehicle (LLRV) activities, a meeting was held at Flight Research Center. Principal participants were Ray White, Leroy Frost, Leonard Ferrier, Joe Walker, Don Mallick, Cal Jarvis, Jim Adkins, Zeon Zwink, Wayne Ottinger, and Gene Matranga.

The session commenced with an estimate of time required to perform each of the functions on the preflight checklist. Review indicated that preflight might be shortened in several ways:

- since the radar altimeter and doppler radar units did not affect safety of flights, it was suggested that radar checks on flight mornings be reduced to a minimum or be performed without inspection coverage;

- addition of ac and dc voltmeters in the cockpit would eliminate need for power checks during the avionics preflight;

- when the weight and drag computer had been properly checked in flight, the weight and drag preflight check could be streamlined down from the 30 minutes currently required; and

- investigate the need to refill H2O2 after prime.

1965 June 30 - .

- Apollo LLRV capabilities - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

In a memorandum to T. Tarbox, John Ryken, Bell Aerosystems Company LLRV Project Manager, said he understood that Dean Grimm of MSC believed that the LLRV was not configured to have the jet engine provide simulation of a constant-lift rocket thrust in addition to providing the 5/6th g lift. Ryken forwarded to Tarbox a copy of a report, "LLRV Automatic Control System Service and Maintenance Manual," plus notes on the system in the hope that these would help him and NASA personnel better understand the system. He also included suggestions about reducing aerodynamic moments which Grimm felt might interfere with LEM simulation.

1965 September - .

- 13 flights made in the Apollo LLRV - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV. A total of 13 flights were made in the LLRV, including one in which the lunar simulation mode was flown for the first time..

1965 September - .

- Thirteen flights made with the Apollo lunar landing research vehicle - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Thirteen flights were made with the lunar landing research vehicle. Two of those flights were devoted to mulling the lunar simulation system; the remaining 11 flights were devoted to research with the attitude control system in the rate command mode. Nine landings were made in the lunar simulation mode.

On flight 1-34-94F the lunar simulation mode worked perfectly and no drift was encountered during more than one minute of hovering flight. The landing was made in the simulation mode for the first time on this flight.

1965 October 8 - .

- Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle flown to 91 m - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

A test model of the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle, designed to simulate lunar landings, was flown by former NASA X-15 pilot Joseph Walker to an altitude of 91 m (300 ft). Built by Bell Aerosystems Company under contract to NASA, the research craft had a jet engine that supported five-sixths of its weight. The pilot manipulated solid-fuel lift rockets that supported the remaining one-sixth, and the craft's attitude was controlled with jets of hydrogen peroxide.

1965 October 19-22 - .

- Apollo LLRV / LLTV issues - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

A meeting was held at Flight Research Center to discuss several items relating to the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) and Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV). Attending were Dean Grimm, Robert Hutchins, Warren North, and Joseph Algranti of MSC; Robert Brown, John Ryken, and Ron Decrevel of Bell Aerosystems Company; and Gene Matranga, Wayne Ottinger, and Arlene Johnson of Flight Research Center.

The discussions centered around MSC's needs for two LLRVs and two LLTVs and the critical nature of the proposed schedules; alternatives of assembling a second LLRV ; clarifying the elements of the work statement; and preliminary talks about writing specifications for the LLTV.

From a schedule standpoint, it was decided that both LLRVs would be delivered to MSC on September 1, 1966. MSC planned to check out and fly the second LLRV (which needed additional systems checkout) with their crew and pilot on a noninterference basis with LLRV No. 1, the primary training vehicle.

1965 October - .

- Seven flights were made with the Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Seven flights were made with the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle at Flight Research Center during October. The first three were in support of X-15 conference activities, and the last four were for attitude control research. Five of the landings were made in the lunar simulation mode.

1965 November 4 - .

- Apollo Lunar Landing Research Vehicle LLRV flight results and problems - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

In a letter to the Director of Flight Research Center, MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth said that recent Lunar Landing Research Vehicle LLRV flight results and problems with the handling qualities of the LEM had focused high interest on the LLRV activities at FRC.

Gilruth concurred with the recent decision to assemble the second LLRV and said MSC planned to support the assembly and checkout of the second vehicle with engineering and contractor personnel assigned to the Flight Crew Operations Directorate.

Gilruth expressed appreciation for the effort expended by FRC in initiating a three-month study contract with Bell Aerosystems to provide drawings for a follow-on vehicle and indicated MSC planned to contract for Lunar Landing Training Vehicles in June 1966.

1965 November - .

- Ten flights were made with the Apollo lunar landing research vehicle - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV. Ten flights were made with the lunar landing research vehicle. All flights were for attitude control and handling qualities research. Landings on all flights were made in the lunar landing mode..

1965 December - .

- 16 flights made in the Apollo LLRV - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

During the month 16 flights were made in the LLRV. Of these, 11 were devoted to concluding the handling qualities evaluation of the rate- command vehicle attitude control system. The other five flights were required to check out a new pilot, Lt. Col. E. E. Kluever of the Army, who would participate in the remaining research flight testing performed on the LLRV at Flight Research Center. On December 15 the craft was grounded for cockpit modifications which would make the pilot display and controllers more like those of the LEM.

1966 August 1 - .

- Three Apollo lunar landing training vehicles approved - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV. NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight George E. Mueller informed MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth that the MSC Procurement Plan for procurement of three lunar landing training vehicles and the proposed flight test program was approved..

1966 December - .

- First LLTV delivered to NASA - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

NASA had accumulated enough data from the LLRV flight program by mid-1966 to give Bell a contract to deliver three LLTV's at a cost of $2.5 million each. In Dec. 1966 vehicle No. 1 was shipped to Houston, followed by No. 2 in Jan. 1967, within weeks of its first flight. Modifications already made to No. 2 had given the pilot a three-axis side control stick and a more restrictive cockpit view, both features of the real Lunar Module that would later be flown by the astronauts down to the moon's surface.

1966 December 13 - .

- Apollo lunar landing research vehicle No 1 received - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

The number one lunar landing research vehicle (LLRV) test vehicle was received at MSC December 13, 1966. Its first flight at Ellington Air Force Base following facility and vehicle checkout was expected about February 1, 1967, with crew training in the vehicle to start about February 20. Additional Details: here....

1967 July 27 - .

- LLRV and LLTV defects - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth wrote MSFC Director Wernher von Braun that MSC had two lunar landing research vehicles (LLRVs) for crew training and three lunar landing training vehicles (LLTVs) were being procured from Bell Aerosystems Go. Gilruth explained that x-ray inspection of welds on the LLTVs at both Bell and MSC had disclosed apparent subsurface defects, such as cracks and lack of fusion. There was, however, question as to the interpretation of the x-rays and the amount of feasible repair. Gilruth mentioned that James Kingsbury of MSFC had previously assisted MSC in interpreting weldment x-rays, stated that further x-rays were being taken, and asked MSFC assistance in interpreting them and in determining the amount and methods of repair needed.

1967 November 7 - .

- Apollo LLTV delayed - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Slayton.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth, wrote Warren B. Hayes, President of Fansteel Metallurgical Corp., that planned schedules for the lunar landing training vehicle (LLTV) could not be maintained because of the need for refabrication of the hydrogen peroxide tanks. The tanks had been manufactured by Airtek Division of Fansteel under contract to Bell Aerosystems Co. Airtek's estimates were that the first of the new tanks would not be available until January 1 968, two months later than required to meet the LLTV program schedule. Gilruth said: "The LLTV is a major and very necessary part of the crew training program for the lunar landing maneuver. It is my hope that Airtek will take every action to assure that the manufacturing cycle time for these tanks is held to an absolute minimum." In preparing background information for Gilruth, Flight Crew Operations Director Donald K. Slayton had pointed out that the first set of tanks (total of eight) had been scrapped because of below-minimum wall thickness. Qualification testing of a tank from the second set revealed out-of-tolerance mismatch of welded tank fittings, and this set was also scrapped.

1967 November 14 - .

- Apollo lunar landing training vehicle capability seen essential - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

A full-time lunar landing training vehicle (LLRV) operating capability was essential to lunar landing training. Optimum proficiency for the critical lunar landing maneuver would be required at launch. Crew participation in the three months or more of concentrated checkout and training at KSC before each lunar mission, coupled with routine launch delays, would make KSC the preferred location for LLRV operating capability.

1968 March 21 - .

- Apollo lunar landing research vehicle in operation - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

The lunar landing research vehicle was operating and training was being conducted, MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth wrote Langley Research Center's Acting Director Charles J. Donlan. MSC intended to conduct a second class for LLRV pilots and one of the first requirements for checkout was a familiarization program on Langley's Lunar Landing Research Facility. He requested that a program be conducted for not less than four nor more than six MSC pilots between April 15 and May 15.

1968 May - .

- LLRV No. 1 destroyed in crash at Houston. - . Nation: USA. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

1968 May 6 - .

- Apollo lunar landing research vehicle No 1 crashed at Ellington Air Force Base - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Armstrong.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Lunar landing research vehicle (LLRV) No. 1 crashed at Ellington Air Force Base, Tex. The pilot, astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, ejected after losing control of the vehicle, landing by parachute with minor injury. Estimated altitude of the LLRV at the time of ejection was 60 meters. LLRV No. 1, which had been on a standard training mission, was a total loss - estimated at $1.5 million. LLRV No. 2 would not begin flight status until the accident investigation had been completed and the cause determined. Additional Details: here....

1968 May 16 - .

- Apollo LLRV-1 Crash Review Board - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

NASA Headquarters established the LLRV-1 Review Board to investigate the May 6 accidental crash of Lunar Landing Research Vehicle No. 1 at Ellington Air Force Base. The Board would consist of: Bruce T. Lundin, Lewis Research Center, chairman; John Stevenson, OMSF; Miles Ross, KSC; James Whitten, Langley Research Center; and Lt. Col. Jeptha D. Oliver (USAF), Norton Air Force Base. J. Wallace Ould, MSC Chief Counsel, would serve as counsel to the group. The board would

- determine the probable cause or causes of the accident,

- identify and evaluate proposed corrective actions,

- evaluate the implications of the accident for LLRV and LM design and operations,

- report its findings to the NASA Administrator as expeditiously as possible but no later than July 15, and

- document its findings and submit a final report to the Administrator with a copy to the NASA Safety Director.

1968 October 17 - .

- Loss of attitude control caused Apollo LLRV Crash - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV,

LM Structural.

Two NASA investigation boards had reported that loss of attitude control caused the May 6 accident that destroyed lunar landing research vehicle No. 1, NASA announced. Helium in propellant tanks had been depleted earlier than normal, dropping pressure needed to force hydrogen peroxide propellant to the attitude-control lift rockets and thrusters. Additional Details: here....

1968 December - .

- LLTV destroyed in crash at Houston. - . Nation: USA. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM. Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV. This was the second accident in 1968, before the first lunar landing. BUt they did not deter Apollo program managers who enthusiastically relied on the vehicles for simulation and training..

1968 December 8 - .

- Apollo lunar landing training vehicle No 1 crashed and burned at Ellington AFB - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

During a routine flight of lunar landing training vehicle (LLTV) No. 1, MSC test pilot Joseph S. Algranti was forced to eject from the craft when it became unstable and he could no longer control the vehicle. The LLTV crashed and burned. A flight readiness review at MSC on November 26 had found the LLTV ready for use in astronaut training, and 10 flight tests had been made before the accident. Additional Details: here....

1968 December 13 - .

- Soviets ponder Apollo 8 - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: Apollo.

Flight: Apollo 8.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Articles appear in the Soviet newspapers explaining the risky nature of the Apollo 8 flight. Meanwhile an LLRV lunar landing trainer has crashed in America - Kamanin notes this is the second loss of an American 'lunar module'. The Apollo 8 flight has been delayed from 18 to 21 December due to engine problems.

Kamanin reviews the organisational structure of the NII-TsPK Gagarin Centre. There is a commander, three deputies, 700 staff, and 12 MiG-21's for flight training (8 single-seat combat aircraft and four two-seat trainers). There are three training tracks for the cosmonauts: Orbital, Lunar, and Military.

1969 March 10 and 31 - .

- Flight Readiness Review Board for Apollo Lunar Landing Training Vehicle No 2 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

A Flight Readiness Review Board convened at MSC to determine the readiness of Lunar Landing Training Vehicle No. 2 and the Flight Crew Operation Directorate for resuming flight test operations. During the briefing and discussion the board agreed that the operation test team was operationally ready. However, a release for resuming flight test operations was withheld until certain open items were resolved. The board reconvened on March 31 and after examination of the open items, agreed that flight testing of LLRV No. 2 should be resumed as soon as possible.

1969 June 13 - .

- Modifications made to Apollo LLTV - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Flight: Apollo 11.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

The NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, in a message to MSC, said he understood that, subsequent to the MSC Flight Readiness Review (FRR) and the NASA Headquarters Readiness Review of the LLTV, additional modifications had been made to that training vehicle. Additional Details: here....

1971 January - .

- LLTV destroyed in crash at Houston. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Slayton.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo LM.

Spacecraft: Apollo LLRV.

Donald 'Deke' Slayton, then NASA's astronaut chief, said there was no other way to simulate a moon landing except by flying the LLTV. LLRV No. 2, the sole survivor, was eventually returned to Dryden, where it is on display as a silent artifact of the Center's contribution to the Apollo program.

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use