Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

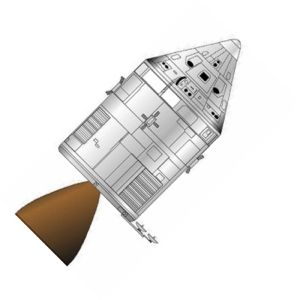

Apollo CSM

Apollo CSM Credit: © Mark Wade |

AKA: Command Service Module. Status: Operational 1967. First Launch: 1967-11-09. Last Launch: 1975-07-15. Number: 17 . Thrust: 97.86 kN (22,000 lbf). Gross mass: 30,329 kg (66,863 lb). Unfuelled mass: 11,841 kg (26,104 lb). Specific impulse: 314 s. Height: 11.03 m (36.18 ft).

Block II CSM's were the only version to fly manned, and they successfully ferried crews to the moon, to the Skylab space station, and to a joint docking with the Russian Soyuz. No production was undertaken after the initial run of 13 Block II capsules - Apollo was abandoned in favor of the Shuttle as the ferry for American manned spaceflight. Forty years later, the Shuttle was to be retired, and a design similar to the Apollo, the CEV, was conceived as the Shuttle's 'replacement'.

Unit Cost $: 77.000 million. Crew Size: 3. Habitable Volume: 6.17 m3. RCS total impulse: 3,774 kgf-sec. Spacecraft delta v: 2,804 m/s (9,199 ft/sec). Electric System: 690.00 kWh. Electric System: 6.30 average kW.

More at: Apollo CSM.

| Apollo CM American manned spacecraft module. 22 launches, 1964.05.28 (Saturn 6) to 1975.07.15 (Apollo (ASTP)). |

| Apollo SM American manned spacecraft module. 22 launches, 1964.05.28 (Saturn 6) to 1975.07.15 (Apollo (ASTP)). |

| Apollo A American manned space station. Study 1961. Apollo A was a lighter-weight July 1961 version of the Apollo spacecraft. |

| Apollo X American manned space station. Study 1963. |

| Apollo Martin 410 American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. The Model 410 was Martin's preferred design for the Apollo spacecraft. |

| Apollo Direct CM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. Conventional spacecraft structures were employed, following the proven materials and concepts demonstrated in the Mercury and Gemini designs. |

| Apollo Direct RM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. The retrograde module supplied the velocity increments required during the translunar portion of the mission up to a staging point approximately 1800 m above the lunar surface. |

| Apollo Direct SM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. The Service Module housed the fuel cells, environmental control, and other major equipment items required for the mission. |

| Apollo Direct TLM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1961. Final letdown, translation hover and landing on the lunar surface from 1800 m above the surface was performed by the terminal landing module. Engine thrust could be throttled down to 1546 kgf. |

| Apollo Direct 2-Man American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. A direct lunar lander design of 1961, capable of being launched to the moon in a single Saturn V launch through use of a 75% scale 2-man Apollo command module. |

| Apollo M-1 American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. Convair/Astronautics preferred M-1 Apollo design was a three-module lunar-orbiting spacecraft. |

| Apollo W-1 American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. Martin's W-1 design for the Apollo spacecraft was an alternative to the preferred L-2C configuration. The 2652 kg command module was a blunt cone lifting body re-entry vehicle, 3.45 m in diameter, 3.61 m long. |

| Apollo D-2 American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1962. The General Electric design for Apollo put all systems and space not necessary for re-entry and recovery into a separate jettisonable 'mission module', joined to the re-entry vehicle by a hatch. |

| Apollo R-3 American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. General Electric's Apollo horizontal-landing alternative to the ballistic D-2 capsule was the R-3 lifting body. This modified lenticular shape provided a lift-to-drag ratio of just 0. |

| Apollo L-2C American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. Martin's L-2C design was the basis for the Apollo spacecraft that ultimately emerged. The 2590 kg command module was a flat-bottomed cone, 3. 91 m in diameter, 2.67 m high, with a rounded apex. |

| Apollo Lenticular American manned spacecraft. Study 1962. The Convair/Astronautics alternate Lenticular Apollo was a flying saucer configuration with the highest hypersonic lift to drag ratio (4.4) of any proposed design. |

| Apollo LES American test vehicle. Flight tests from a surface pad of the Apollo Launch Escape System using a boilerplate capsule. |

| Apollo CSM Boilerplate American manned spacecraft. Boilerplate structural Apollo CSM's were used for various systems and booster tests, especially proving of the LES (launch escape system). |

| Apollo CSM Block I American manned spacecraft. The Apollo Command Service Module was the spacecraft developed by NASA in the 1960's as a standard spacecraft for earth and lunar orbit missions. |

| FIRE American re-entry vehicle technology satellite. 2 launches, 1964.04.14 (FIRE 1) and 1965.05.22 (FIRE 2). Suborbital re-entry test program that used a subscale model of the Apollo Command Module to verify the configuration at high reentry speed. Reentry Technology satellite built by Republic Aviation Corporation for NASA. |

| Apollo MSS American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1965. The Apollo Mapping and Survey System was a kit of photographic equipment that was at one time part of the basic Apollo Block II configuration. |

| Apollo Experiments Pallet American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1965. The Apollo Experiments Pallet was a sophisticated instrument payload that would have been installed in the Apollo CSM for dedicated lunar or earth orbital resource assessment missions. |

| Apollo SMLL American lunar logistics spacecraft. Study 1966. North American Aviation (NAA) proposed use of the SM as a lunar logistics vehicle (LLV) in 1966. The configuration, simply stated, put a landing gear on the SM. |

| Apollo CMLS American manned lunar habitat. Study 1966. |

| Apollo RM American logistics spacecraft. Study 1967. In 1967 it was planned that Saturn IB-launched Orbital Workshops would be supplied by Apollo CSM spacecraft and Resupply Modules (RM) with up to three metric tons of supplies and instruments. |

| Apollo 120 in Telescope American manned space station. Study 1968. Concept for use of a Saturn V-launched Apollo CSM with an enormous 10 m diameter space laboratory equipped with a 3 m diameter astronomical telescope. |

| Apollo LMAL American manned space station. Study 1968. |

| Apollo Rescue CSM American manned rescue spacecraft. Study 1970. Influenced by the stranded Skylab crew portrayed in the book and movie 'Marooned', NASA provided a crew rescue capability for the first time in its history. |

| Apollo ASTP Docking Module American manned space station module. Docking Module 2. The ASTP docking module was basically an airlock with docking facilities on each end to allow crew transfer between the Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft. |

| Apollo CM Escape Concept American manned rescue spacecraft. Study 1976. Escape capsule using Apollo command module studied by Rockwell for NASA for use with the shuttle in the 1970's-80's. Mass per crew: 750 kg. |

| Apollo LM&SS 1, 2, 3, 4 (Upward 1, 2, 3, 4) Null |

Family: Lunar Orbiters, Moon. Country: USA. Engines: AJ10-137. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing, Apollo CM, Apollo SM, LESA Lunar Base, Skylab, AES Lunar Base, ALSS Lunar Base. Flights: Apollo 7, Apollo 8, Apollo 9, Apollo 10, Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 13, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16, Apollo 17, Skylab 2, Skylab 3, Skylab 4, Apollo (ASTP). Launch Vehicles: Little Joe II, Saturn I, Saturn IB, Saturn V. Propellants: N2O4/UDMH. Projects: Apollo, ASTP. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral, Cape Canaveral LC34, Cape Canaveral LC37B, Cape Canaveral LC39A, Cape Canaveral LC39B. Agency: NASA, North American. Bibliography: 148, 16, 160, 18, 183, 2, 22, 2383, 2385, 2387, 2388, 2389, 2391, 2392, 2395, 2397, 2398, 2400, 2402, 2405, 2406, 2407, 2408, 2409, 2410, 26, 27, 279, 30, 33, 366, 376, 431, 452, 6, 60, 66, 6345, 12051, 12052.

| Apollo 15 CSM Apollo 15 CSM over Lunar Surface Credit: NASA |

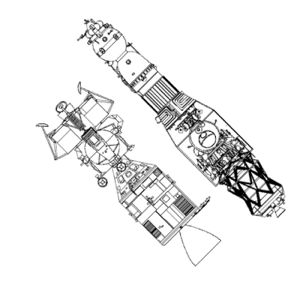

| Apollo CSM / LM Apollo Command Service Module and Lunar Module Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM |

| Apollo vs N1-L3 Apollo CSM / LM vs L3 Lunar Complex Credit: © Mark Wade |

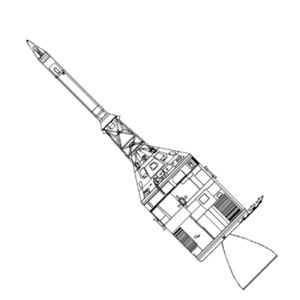

| Apollo CSM Apollo CSM with Launch Escape Tower Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo CSM Interior Interior of the Apollo Command Service Module on display at Kennedy Space Centre, Florida. Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Apollo 10 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Saturn 6 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Apollo with Vanes Credit: NASA |

| Convair Apollo Credit: NASA |

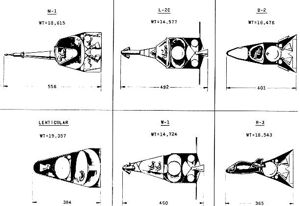

| Apollo Competitors Credit: NASA |

1957 October 14 - .

- National space flight program proposed - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

The Rocket and Satellite Research Panel, established in 1946 as the V-2 Upper Atmosphere Research Panel and renamed the Upper Atmosphere Rocket Research Panel in 1948, together with the American Rocket Society proposed a national space flight program and a unified National Space Establishment. The mission of such an Establishment would be nonmilitary in nature, specifically excluding space weapons development and military operations in space. By 1959, this Establishment should have achieved an unmanned instrumented hard lunar landing and, by 1960, an unmanned instrumented lunar satellite and soft lunar landing. Manned circumnavigation of the moon with return to earth should have been accomplished by 1965 with a manned lunar landing mission taking place by 1968. Beginning in 1970, a permanent lunar base should be possible.

1958 January 12 - .

- Special Committee on Space Technology established - . Nation: USA. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. NACA established a Special Committee on Space Technology to study the problems of space flight. H. Guyford Stever of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was named Chairman. On November 21, 1957, NACA had authorized formation of the Committee..

1958 October 25 - .

- Stever Committee report on the civilian space program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

The Stever Committee, which had been set up on January 12, submitted its report on the civilian space program to NASA. Among the recommendations:

- A vigorous, coordinated attack should be made upon the problems of maintaining the performance capabilities of man in the space environment as a prerequisite to sophisticated space exploration.

- Sustained support should be given to a comprehensive instrumentation development program, establishment of versatile dynamic flight simulators, and provision of a coordinated series of vehicles for testing components and subsystems.

- Serious study should be made of an equatorial launch capability.

- Lifting reentry vehicles should be developed.

- Both the clustered- and single-engine boosters of million-pound thrust should be developed.

- Research on high-energy propellant systems for launch vehicle upper stages should receive full support.

- The performance capabilities of various combinations of existing boosters and upper stages should be evaluated, and intensive development concentrated on those promising greatest usefulness in different categories of payload.

1959 February 5 - .

- Working Group on Lunar Exploration established by NASA - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

A Working Group on Lunar Exploration was established by NASA at a meeting at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Members of NASA, JPL, Army Ballistic Missile Agency, California Institute of Technology, and the University of California participated in the meeting. The Working Group was assigned the responsibility of preparing a lunar exploration program, which was outlined: circumlunar vehicles, unmanned and manned; hard lunar impact; close lunar satellites; soft lunar landings (instrumented). Preliminary studies showed that the Saturn booster with an intercontinental ballistic missile as a second stage and a Centaur as a third stage, would be capable of launching manned lunar circumnavigation spacecraft and instrumented packages of about one ton to a soft landing on the moon.

1959 February 17 - .

- Exploration of the moon a NASA responsibility - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Roy.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Roy W. Johnson, Director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), testified before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics that DOD and ARPA had no lunar landing program. Herbert F. York, DOD Director of Defense Research and Engineering, testified that exploration of the moon was a NASA responsibility.

1959 June 25-26 - .

- Steps toward a manned lunar landing - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

At the second meeting of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight, held at the Ames Research Center, members presented reports on intermediate steps toward a manned lunar landing and return.

Bruce T. Lundin of the Lewis Research Center reported to members on propulsion requirements for various modes of manned lunar landing missions, assuming a 10,000-pound spacecraft to be returned to earth. Lewis mission studies had shown that a launch into lunar orbit would require less energy than a direct approach and would be more desirable for guidance, landing reliability, etc. From a 500,000 foot orbit around the moon, the spacecraft would descend in free fall, applying a constant-thrust decelerating impulse at the last moment before landing. Research would be needed to develop the variable-thrust rocket engine to be used in the descent. With the use of liquid hydrogen, the launch weight of the lunar rocket and spacecraft would be 10 to 11 million pounds. Additional Details: here....

1959 August-September - .

- Meetings of the STG New Projects Panel to discuss an advanced manned space flight program - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. Meetings of the STG New Projects Panel to discuss an advanced manned space flight program. .

1959 August 12 - .

- NASA's future manned space program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Parachute,

CSM Source Selection.

The STG New Projects Panel (proposed by H. Kurt Strass in June) held its first meeting to discuss NASA's future manned space program. Present were Strass, Chairman, Alan B. Kehlet, William S. Augerson, Jack Funk, and other STG members. Strass summarized the philosophy behind NASA's proposed objective of a manned lunar landing : maximum utilization of existing technology in a series of carefully chosen projects, each of which would provide a firm basis for the next step and be a significant advance in its own right. Additional Details: here....

1959 August 12 - .

- The New Projects Panel of Space Task Group (STG) met for the first time. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

Gemini Parachute.

The New Projects Panel of Space Task Group (STG) met for the first time, with H. Kurt Strass in the chair. The panel was to consider problems related to atmospheric reentry at speeds approaching escape velocity, maneuvers in the atmosphere and space, and parachute recovery for earth landing. Alan B. Kehlet of STG's Flight Systems Division was assigned to initiate a program leading to a second-generation capsule incorporating several advances over the Mercury spacecraft: It would carry three men; it would be able to maneuver in space and in the atmosphere; the primary reentry system would be designed for water landing, but land landing would be a secondary goal. At the next meeting, on August 18, Kehlet offered some suggestions for the new spacecraft. The ensuing discussion led panel members to agree that a specifications list should be prepared as the first step in developing an engineering design requirement.

1959 August 18 - .

- First major new NASA project to be a second-generation reentry capsule - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

At its second meeting, STG's New Projects Panel decided that the first major project to be investigated would be the second-generation reentry capsule. The Panel was presented a chart outlining the proposed sequence of events for manned lunar mission system analysis. The target date for a manned lunar landing was 1970.

1959 August 31 - .

- Lunar flights to originate from space platforms in earth orbit - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

A House Committee Staff Report stated that lunar flights would originate from space platforms in earth orbit according to current planning. The final decision on the method to be used, "which must be made soon," would take into consideration the difficulty of space rendezvous between a space platform and space vehicles as compared with the difficulty of developing single vehicles large enough to proceed directly from the earth to the moon.

1959 September - .

- MIT study of the guidance and control design for a variety of space missions - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Guidance, CSM Source Selection. A study of the guidance and control design for a variety of space missions began at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory under a NASA contract..

1959 September 28 - .

- Lenticular-shaped vehicle proposed for the lunar mission - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

At the third meeting of STG's New Projects Panel, Alan B. Kehlet presented suggestions for the multimanned reentry capsule. A lenticular-shaped vehicle was proposed, to ferry three occupants safely to earth from a lunar mission at a velocity of about 36,000 feet per second.

1959 November 19 - .

- Importance of weight of end vehicle in the lunar landing mission - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

In a memorandum to the members of the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight, Chairman Harry J. Goett discussed the increased importance of the weight of the "end vehicle" in the lunar landing mission. This was to be an item on the agenda of the third meeting of the Committee, to be held in early December. Abe Silverstein, Director of the NASA Office of Space Flight Development, had recently mentioned to Goett that a decision would be made within the next few weeks on the configuration of successive generations of Saturn, primarily the upper stages, Silverstein and Goett had discussed the Committee's views on a lunar spacecraft. Goett expressed the hope in the memorandum that members of the Committee would have some specific ideas at their forthcoming meeting about the probable weight of the spacecraft.

In addition, Goett informed the Committee that the Vega had been eliminated as a possible booster for use in one of the intermediate steps leading to the lunar mission. The primary possibility for the earth satellite mission was now the first-generation Saturn and for the lunar flight the second-generation Saturn.

1960 January 28 - .

- NASA's Ten-Year Plan presented to Congress - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Glennan.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

In testimony before the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Richard E. Horner, Associate Administrator of NASA, presented NASA's ten-year plan for 1960-1970. The essential elements had been recommended by the Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight. NASA's Office of Program Planning and Evaluation, headed by Homer J. Stewart, formalized the ten-year plan.

On February 19, NASA officials again presented the ten-year timetable to the House Committee. A lunar soft landing with a mobile vehicle had been added for 1965. On March 28, NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan described the plan to the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences. He estimated the cost of the program to be more than $1 billion in Fiscal Year 1962 and at least $1.5 billion annually over the next five years, for a total cost of $12 to $15 billion. Additional Details: here....

1960 January - .

- Name Apollo suggested - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Gilruth,

Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

At a luncheon in Washington, Abe Silverstein, Director of the Office of Space Flight Programs, suggested the name "Apollo" for the manned space flight program that was to follow Mercury. Others at the luncheon were Don R. Ostrander from NASA Headquarters and Robert R. Gilruth, Maxime A. Faget, and Charles J. Donlan from STG.

1960 March 3-5 - .

- Advanced manned space flight program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

At a NASA staff conference at Monterey, Calif., officials discussed the advanced manned space flight program, the elements of which had been presented to Congress in January. The Goddard Space Flight Center was asked to define the basic assumptions to be used by all groups in the continuing study of the lunar mission. Some problems already raised were: the type of heatshield needed for reentry and tests required to qualify it, the kind of research and development firings, and conditions that would be encountered in cislunar flight. Additional Details: here....

1960 March 8 - .

- Preliminary guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. STG formulated preliminary guidelines by which an "advanced manned spacecraft and system" would be developed. These guidelines were further refined and elaborated; they were formally presented to NASA Centers during April and May..

1960 April 1-May 3 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Guidelines for an advanced manned spacecraft program presented by STG - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

Members of STG presented guidelines for an advanced manned spacecraft program to NASA Centers to enlist research assistance in formulating spacecraft and mission design.

To open these discussions, Director Robert R. Gilruth summarized the guidelines: manned lunar reconnaissance with a lunar mission module, corollary earth orbital missions with a lunar mission module and with a space laboratory, compatibility with the Saturn C-1 or C-2 boosters (weight not to exceed 15,000 pounds for a complete lunar spacecraft and 25,000 pounds for an earth orbiting spacecraft), 14-day flight time, safe recovery from aborts, ground and water landing and avoidance of local hazards, point (ten square-mile) landing, 72-hour postlanding survival period, auxiliary propulsion for maneuvering in space, a "shirtsleeve" environment, a three-man crew, radiation protection, primary command of mission on board, and expanded communications and tracking facilities. In addition, a tentative time schedule was included, projecting multiman earth orbit qualification flights beginning near the end of the first quarter of calendar year 1966.

1960 April 1-May 3 - .

- Command and communications guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft program listed - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

Command and communications guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft program were listed by STG's Robert G. Chilton at NASA Centers:

- Primary command of the mission should be on board. Since a manned spacecraft would necessarily be much more complex and its cost much greater than an unmanned spacecraft, maximum use should be made of the command decision and operational capabilities of the crew. Studies would be needed to determine the extent of these capabilities under routine, urgent, and extreme emergency conditions. Onboard guidance and navigation hardware would include inertial platforms for monitoring insertion guidance, for abort command, and for abort-reentry navigation; optical devices; computers; and displays. Attitude control would require a multimode system.

- Communications and ground tracking should be provided throughout the mission except when the spacecraft was behind the moon. Voice contact once per orbit was considered sufficient for orbital missions. For the lunar mission, telemetry would be required only for backup data since the crew would relay periodic voice reports. Television might be desirable for the lunar mission. For ground tracking, a study of the Mercury system would determine whether the network could be modified and relocated to satisfy the close-in requirements of a lunar mission. The midcourse and circumlunar tracking requirements might be met by the deep-space network facilities at Goldstone, Calif., Australia, and South Africa. Both existing and proposed facilities should be studied to ensure that frequencies for all systems could be made compatible to permit use of a single beacon for midcourse and reentry tracking.

1960 April 1-May 3 - .

- Guidelines for human factors in the advanced manned spacecraft program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

Stanley C. White of STG outlined at NASA Centers the guidelines for human factors in the advanced manned spacecraft program:

- A "shirtsleeve" spacecraft environment would be necessary because of the long duration of the lunar flight. This would call for a highly reliable pressurized cabin and some means of protection against rapid decompression. Such protection might be provided by a quick-donning pressure suit. Problems of supplying oxygen to the spacecraft; removing carbon dioxide, water vapor, toxic gases, and microorganisms from the capsule atmosphere; basic monitoring instrumentation; and restraint and couch design were all under study. In addition, research would be required on noise and vibration in the spacecraft, nutrition, waste disposal, interior arrangement and displays, and bioinstrumentation.

- A minimum crew of three men was specified. Studies had indicated that, for a long-duration mission, multiman crews were necessary and that three was the minimum number required.

- The crew should not be subjected to more than a safe radiation dose. Studies had shown that it was not yet possible to shield the crew against a solar flare. Research was indicated on structural materials and equipment for radiation protection, solar-flare prediction, minimum radiation trajectories, and the radiation environment in cislunar space.

1960 April 1-May 3 - .

- Advanced manned spacecraft program guidelines for aborted missions and landing - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Recovery,

CSM Source Selection.

In discussing the advanced manned spacecraft program at NASA Centers, Maxime A. Faget of STG detailed the guidelines for aborted missions and landing:

- The spacecraft must have a capability of safe crew recovery from aborted missions at any speed up to the maximum velocity, this capability to be independent of the launch propulsion system.

- A satisfactory landing by the spacecraft on both water and land, avoiding local hazards in the recovery area, was necessary. This requirement was predicated on two considerations: emergency conditions or navigation errors could force a landing on either water or land; and accessibility for recovery and the relative superiority of land versus water landing would depend on local conditions and other factors. The spacecraft should be able to land in a 30-knot wind, be watertight, and be seaworthy under conditions of 10- to 12-foot waves.

- Planned landing capability by the spacecraft at one of several previously designated ground surface locations, each approximately 10 square miles in area, would be necessary. Studies were needed to assess the value of impulse maneuvers, guidance quality, and aerodynamic lift over drag during the return from the lunar mission. Faget pointed out that this requirement was far less severe for the earth orbit mission than for the lunar return.

- The spacecraft design should provide for crew survival for at least 72 hours after landing. Because of the unpredictability of possible emergency maneuvers, it would be impossible to provide sufficient recovery forces to cover all possible landing locations. The 72-hour requirement would permit mobilization of normally existing facilities and enough time for safe recovery. Locating devices on the spacecraft should perform adequately anywhere in the world.

- Auxiliary propulsion should be provided for guidance maneuvers needed to effect a safe return in a launch emergency. Accuracy and capability of the guidance system should be studied to determine auxiliary propulsion requirements. Sufficient reserve propulsion should be included to accommodate corrections for maximum guidance errors. The single system could serve for either guidance maneuvers or escape propulsion requirements.

1960 April-May - .

- Guidelines for an advanced manned spacecraft program - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. Presentation by STG members of the guidelines for an advanced manned spacecraft program to NASA Centers..

1960 April 15 - .

- STG brief advanced manned spacecraft program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

STG members, visiting Moffett Field, Calif., briefed representatives of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Flight Research Center, and Ames Research Center on the advanced manned spacecraft program. Ames representatives then described work at their Center which would be applicable to the program: preliminary design studies of several aerodynamic configurations for reentry from a lunar trajectory, guidance and control requirements studies, potential reentry heating experiments at near-escape velocity, flight simulation, and pilot display and navigation studies. STG asked Ames to investigate heating and aerodynamics on possible lifting capsule configurations. In addition, Ames offered to tailor a payload applicable to the advanced program for a forthcoming Wallops Station launch.

1960 April 15 - .

- Guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft program presented by STG - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. Briefings on the guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft program were presented by STG representatives at NASA Headquarters..

1960 April 18 - .

- Space Exploration Program Council - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

In a memorandum to NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan, Robert L. King, Executive Secretary of the Space Exploration Program Council (SEPC), reported on the status of certain actions taken up at the first meeting of the Council:

- Rather than appoint a separate Senior Steering Group to resolve policy problems connected with the reliability program, SEPC itself tentatively would be used. A working committee would be appointed for each major system and would and rely on the SEPC for broad policy guidance,

- Proposed rescheduling of the first Atlas-Agena 13 lunar mission for an earlier flight date was abandoned as impractical.

1960 May 2 - .

- Proposed advanced manned spacecraft program presented to von Braun - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Members of STG presented the proposed advanced manned spacecraft program to Wernher von Braun and 25 of his staff at Marshall Space Flight Center. During the ensuing discussion, the merits of a completely automatic circumlunar mission were compared with those of a manually operated mission. Further discussions were scheduled.

1960 May 3 - .

- Proposed advanced manned spacecraft program presented to Lewis Research Center - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

STG members presented the proposed advanced manned spacecraft program to the Lewis Research Center staff. Work at the Center applicable to the program included: analysis and preliminary development of the onboard propulsion system, trajectory analysis, and development of small rockets for midcourse and attitude control propulsion.

1960 May 12 - .

- Discussion on the advanced manned spacecraft program at Langley - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

A discussion on the advanced manned spacecraft program was held at the Langley Research Center with members of STG and Langley Research Center, together with George M. Low and Ernest O. Pearson, Jr., of NASA Headquarters and Harry J. Goett of Goddard Space Flight Center. Floyd L. Thompson, Langley Director, said that Langley would be studying the radiation problem, making configuration tests (including a lifting Mercury) , and studying aerodynamics, heating, materials, and structures.

1960 May 25 - .

- Advanced Vehicle Team to make preliminary design for advanced multiman spacecraft - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Gilruth, Maynard. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM. STG formed the Advanced Vehicle Team, reporting directly to Robert R. Gilruth, Director of the Mercury program. The Team would conduct research and make preliminary design studies for an advanced multiman spacecraft.. Additional Details: here....

1960 June 21 - .

- Radiation and its effect on manned space flight - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

Robert O. Piland, Head of the STG Advanced Vehicle Team, and Stanley C. White of STG attended a meeting in Washington, D. C., sponsored by the NASA Office of Life Sciences Programs, to discuss radiation and its effect on manned space flight. Their research showed that it would be impracticable to shield against the inner Van Allen belt radiation but possible to shield against the outer belt with a moderate amount of protection. Additional Details: here....

1960 July 25 - .

- Name Apollo approved for the advanced manned space flight program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Glennan,

Goett,

Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

NASA Director of Space Flight Programs Abe Silverstein notified Harry J. Goett, Director of the Goddard Space Flight Center, that NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan had approved the name "Apollo" for the advanced manned space flight program. The program would be so designated at the forthcoming NASA-Industry Program Plans Conference.

1960 July 28-29 - .

- Announcement of the Apollo program to American industry - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

The first NASA-Industry Program Plans Conference was held in Washington, D.C. The purpose was to give industrial management an overall picture of the NASA program and to establish a basis for subsequent conferences to be held at various NASA Centers. The current status of NASA programs was outlined, including long-range planning, launch vehicles, structures and materials research, manned space flight, and life sciences.

NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh L. Dryden announced that the advanced manned space flight program had been named "Apollo." George M. Low, NASA Chief of Manned Space Flight, stated that circumlunar flight and earth orbit missions would be carried out before 1970. This program would lead eventually to a manned lunar landing and a permanent manned space station. Additional Details: here....

1960 July 28 - .

- Apollo Program Announced - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Silverstein. Program: Apollo. Class: Moon. Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. Name 'Apollo' selected by Silverstein. Conference with aerospace industry outlined NASA's plans for circumlunar and lunar flight..

1960 August 8 - .

- Tentative program of the Goddard industry conference to be held on August 30 outlined - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

In a memorandum to Abe Silverstein, Director of NASA's Office of Space Flight Programs, Harry J. Goett, Director of Goddard Space Flight Center, outlined the tentative program of the Goddard industry conference to be held on August 30. At this conference, more details of proposed study contracts for an advanced manned spacecraft would be presented. The requirements would follow the guidelines set down by STG and presented to NASA Headquarters during April and May. Three six-month study contracts at $250,000 each would be awarded.

1960 August 30 - .

- Industry briefing on feasibility studies for the Apollo spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

The Goddard Space Flight Center GSFC conducted its industry conference in Washington, D.C., presenting details of GSFC projects, current and future. The objectives of the proposed six-month feasibility contracts for an advanced manned spacecraft were announced. Additional Details: here....

1960 September 13 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Apollo Study Bidder's Conference - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Moon. Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, Apollo Lunar Landing, CSM ECS, CSM Source Selection. Bidder's conference for circumlunar Apollo. Specification: Saturn C-2 compatability (6,800 kg mass for circumlunar mission); 14 day flight time; three-man crew in shirt-sleeve environment..

1960 September 13 - .

- STG briefing for prospective bidders for Apollo - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. An STG briefing was held at Langley Field, Va., for prospective bidders on three six-month feasibility studies of an advanced manned spacecraft as part of the Apollo program. A formal Request for Proposal was issued at the conference..

1960 September 30 - October 3 - .

- STG Evaluation Board for advanced manned spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Charles J. Donlan of STG, Chairman of the Evaluation Board which would consider contractors' proposals on feasibility studies for an advanced manned spacecraft, invited the Directors of Ames Research Center, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Flight Research Center, Lewis Research Center, Langley Research Center, and Marshall Space Flight Center to name representatives to the Evaluation Board. The first meeting was to be held on October 10 at Langley Field, Va.

1960 October 4 - .

- Evaluation Boards formed to consider industry proposals for Apollo spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Goett.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Members were appointed to the Technical Assessment Panels and the Evaluation Board to consider industry proposals for Apollo spacecraft feasibility studies. Members of the Evaluation Board were: Charles J. Donlan (STG), Chairman; Maxime A. Faget (STG) ; Robert O. Piland (STG), Secretary; John H. Disher (NASA Headquarters Office of Space Flight Programs); Alvin Seiff (Ames); John V. Becker (Langley); H. H. Koelle (Marshall); Harry J. Goett (Goddard), ex officio; and Robert R. Gilruth (STG), ex officio.

1960 October 9 - .

- Contractors' proposals for an advanced manned spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Contractors' proposals on feasibility studies for an advanced manned spacecraft were received by STG. Sixty-four companies expressed interest in the Apollo program, and of these 14 actually submitted proposals: The Boeing Airplane Company; Chance Vought Corporation; Convair/Astronautics Division of General Dynamics Corporation; Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, Inc.; Douglas Aircraft Company; General Electric Company; Goodyear Aircraft Corporation; Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation; Guardite Division of American Marietta Company; Lockheed Aircraft Corporation; The Martin Company; North American Aviation, Inc.; and Republic Aviation Corporation. These 14 companies, later reduced to 12 when Cornell and Guardite withdrew, were subsequently invited to submit prime contractor proposals for the Apollo spacecraft development in 1961. The Technical Assessment Panels began evaluation of contractors' proposals on October 10.

1960 October 21 - .

- Evaluation completed on proposals for an advanced manned spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

The Technical Assessment Panels presented to the Evaluation Board their findings on the contractors' proposals for feasibility studies of an advanced manned spacecraft. On October 24, the Evaluation Board findings and recommendations were presented to the STG Director.

1960 October 21 - .

- Design constraints for in-house study of the Apollo spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

A staff meeting of STG's Flight Systems Division was held to fix additional design constraints for the in- house design study of the Apollo spacecraft.

Fundamental decisions were made as a result of this and a previous meeting on September 20.. Additional Details: here....

1960 October 25 - .

- Convair, General Electric, and Martin selected to prepare Apollo spacecraft feasibility studies - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

NASA selected three contractors to prepare individual feasibility studies of an advanced manned spacecraft as part of Project Apollo. The contractors were Convair/Astronautics Division of General Dynamics Corporation, General Electric Company, and The Martin Company.

1960 October 25 - .

- Apollo Initial Study Contracts - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Moon. Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. From 16 bids, Convair, General Electric, and Martin selected to conduct $250,000 study contracts. Meanwhile Space Task Group Langley undertakes its own studies, settling on Apollo CM configuration as actually built by October 1960..

1960 October 27 - November 2 - .

- General Electric, Martin, and General Dynamics negotiate Apollo systems study contracts - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Representatives of the General Electric Company, The Martin Company, and Convair/Astronautics Division of General Dynamics Corporation visited STG to conduct negotiations on the Apollo systems study contracts announced on October 25. The discussions clarified or identified areas not completely covered in company proposals. Contracts were awarded on November 15.

1960 November 22 - .

- MIT navigation and guidance support for Project Apollo - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Guidance,

CSM Source Selection.

STG held a meeting at Goddard Space Flight Center to discuss a proposed contract with MIT Instrumentation Laboratory for navigation and guidance support for Project Apollo. The proposed six-month contract for $100,000 might fund studies through the preliminary design stage but not actual hardware. Milton B. Trageser of the Instrumentation Laboratory presented a draft work statement which divided the effort into three parts: midcourse guidance, reentry guidance, and a satellite experiment feasibility study using the Orbiting Geophysical Observatory. STG decided that the Instrumentation Laboratory should submit a more detailed draft of a work statement to form the basis of a contract. In a discussion the next day, Robert G. Chilton of STG and Trageser clarified three points:

- The current philosophy was that an onboard computer program for a normal mission sequence would be provided and would be periodically updated by the crew. If the crew were disabled, the spacecraft would continue on the programmed flight for a normal return. No capability would exist for emergency procedures.

- Chilton emphasized that consideration of the reentry systems design should include all the guideline requirements for insertion monitoring by the crew, navigation for aborted missions, and, in brief, the whole design philosophy for manned flight.

- The long-term objective of a lunar landing mission should be kept in mind although design simplicity was of great importance.

1960 November 29 - .

- Briefing on the Apollo and Saturn programs - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

A joint briefing on the Apollo and Saturn programs was held at Marshall Space Flight Center MSFC, attended by representatives of STG and MSFC. Maxime A. Faget of STG and MSFC Director Wernher von Braun agreed that a joint STG-MSFC program would be developed to accomplish a manned lunar landing. Areas of responsibility were: MSFC launch vehicle and landing on the moon; STG - lunar orbit, landing, and return to earth.

1960 December 2 - .

- Study program on the guidance aspects of Project Apollo - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Guidance,

CSM Source Selection.

Milton B. Trageser of MIT Instrumentation Laboratory transmitted to Charles J. Donlan of STG the outline of a study program on the guidance aspects of Project Apollo. He outlined what might be covered by a formal proposal on the Apollo spacecraft guidance and navigation contract discussed by STG and Instrumentation Laboratory representatives on November 22.

1960 December 6-8 - .

- First technical review of the General Electric Apollo feasibility study - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

The first technical review of the General Electric Company Apollo feasibility study was held at the contractor's Missile and Space Vehicle Department. Company representatives presented reports on the study so that STG representatives might review progress, provide General Electric with pertinent information from NASA or other sources, and discuss and advise as to the course of the study.

1960 December 7-9 - .

- Martin presented the first technical review of its Apollo feasibility study - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Recovery,

CSM Source Selection.

The Martin Company presented the first technical review of its Apollo feasibility study to STG officials in Baltimore, Md. At the suggestion of STG, Martin agreed to reorient the study in several areas: putting more emphasis on lunar orbits, putting man in the system, and considering landing and recovery in the initial design of the spacecraft.

1960 December 14-15 - .

- Frst technical review of the Convair Apollo feasibility study - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Convair/Astronautics Division of the General Dynamics Corporation held its first technical review of the Apollo feasibility study in San Diego, Calif. Brief presentations were made by contractor and subcontractor technical specialists to STG representatives. Convair/Astronautics' first approach was oriented toward the modular concept, but STG suggested that the integral spacecraft concept should be investigated.

1960 December 22 - .

- MIT proposal for a study of a navigation and guidance system for Apollo - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Guidance, CSM Source Selection. The MIT Instrumentation Laboratory submitted a formal proposal to NASA for a study of a navigation and guidance system for the Apollo spacecraft..

1961 January 6 - .

- Low Committee established - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Manned Lunar Landing Task Group (Low Committee) set up by the Space Exploration Program Council was instructed to prepare a position paper for the NASA Fiscal Year 1962 budget presentation to Congress. The paper was to be a concise statement of NASA's lunar program for Fiscal Year 1962 and was to present the lunar mission in term of both direct ascent and rendezvous. The rendezvous program would be designed to develop a manned spacecraft capability in near space, regardless of whether such a technique would be needed for manned lunar landing. In addition to answering such questions as the reason for not eliminating one of the two mission approaches, the Group was to estimate the cost of the lunar mission and the date of its accomplishment, though not in specific terms. Although the decision to land a man on the moon had not been approved, it was to be stressed that the development of the scientific and technical capability for a manned lunar landing was a prime NASA goal, though not the only one. The first meeting of the Group was to be held on January 9.

1961 January 9 - . LV Family: Nova. Launch Vehicle: Nova 4L.

- First meeting of the Manned Lunar Landing Task Group - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

Apollo Lunar Landing,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

At the first meeting of the Manned Lunar Landing Task Group, Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., Director of the Office of Space Flight Programs Abe Silverstein, and Director of the Office of Advanced Research Programs Ira H. Abbott outlined the purpose of the Group to the members. After a discussion of the instructions, the Group considered first the objectives of the total NASA program:

- the exploration of the solar system for knowledge to benefit mankind; and

- the development of technology to permit exploitation of space flight for scientific, military, and commercial uses.

- a manned landing on the moon with return to earth,

- limited manned lunar exploration, and

- a scientific lunar base.

1961 January 10 - .

- STG briefed on Convair Apollo feasibility study - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Representatives of STG visited Convair Astronautics Division of the General Dynamics Corporation to monitor the Apollo feasibility study contract. The meeting consisted of several individual informal discussions between the STG and Convair specialists on configurations and aerodynamics, heating, structures and materials, human factors, trajectory analysis, guidance and control, and operation implementation.

1961 January 11 - .

- Briefing given to the Saturn Guidance Committee on the Apollo program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

J. Thomas Markley of the Apollo Spacecraft Project Office reported to Associate Director of STG Charles J. Donlan that an informal briefing had been given to the Saturn Guidance Committee on the Apollo program. The Committee had been formed by Don R. Ostrander, NASA Director of the Office of Launch Vehicle Programs, to survey the broad guidance and control requirements for Saturn. The Committee was to review Marshall Space Flight Center guidance plans, review plans of mission groups who intended to use Saturn, recommend an adequate guidance system for Saturn, and prepare a report of the evaluation and results during January. Members of STG, including Robert O. Piland, Markley, and Robert G. Chilton, presented summaries of the overall Apollo program and guidance requirements for Apollo.

1961 January 11 - .

- Three of the Apollo Technical Liaison Groups held their first meetings - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

Three of the Apollo Technical Liaison Groups (Trajectory Analysis, Heating, and Human Factors) held their first meetings at the Ames Research Center.

After reviewing the status of the contractors' Apollo feasibility studies, the Group on Trajectory Analysis discussed studies being made at NASA Centers. An urgent requirement was identified for a standard model of the Van Allen radiation belt which could be used in all trajectory analysis related to the Apollo program,

The Group on Heating, after consideration of NASA and contractor studies currently in progress, recommended experimental investigation of control surface heating and determination of the relative importance of the unknowns in the heating area by relating estimated "ignorance" factors to resulting weight penalties in the spacecraft. The next day, three members of this Group met for further discussions and two areas were identified for more study: radiant heat inputs and their effect on the ablation heatshield, and methods of predicting heating on control surfaces, possibly by wind tunnel tests at high Mach numbers.

The Group on Human Factors considered contractors' studies and investigations being done at NASA Centers. In particular, the Group discussed the STG document, "Project Apollo Life Support Programs," which proposed 41 research projects. These projects were to be carried out by various organizations, including NASA, DOD, industry, and universities. Medical support experience which might be applicable to Apollo was also reviewed.

1961 January 12-13 - .

- Martin progress on the Apollo feasibility study contract - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Recovery,

CSM Source Selection.

Representatives of STG visited The Martin Company in Baltimore, Md., to review the progress of the Apollo feasibility study contract. Discussions on preliminary design of the spacecraft, human factors, propulsion, power supplies, guidance and control, structures, and landing and recovery were held with members of the Martin staff.

1961 January 12 - .

- First meetings of three of the Apollo Technical Liaison Groups - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

Three of the Apollo Technical Liaison Groups Structures and Materials, Configurations and Aerodynamics, and Guidance and Control held their first meetings at the Ames Research Center.

The Group on Structures and Materials, after reviewing contractors' progress on the Apollo feasibility studies, considered reports on Apollo-related activities at NASA Centers. Among these activities were work on the radiative properties of material suitable for temperature control of spacecraft (Ames), investigation of low-level cooling systems in the reentry module (Langley), experiments on the landing impact of proposed reentry module shapes (Langley), meteoroid damage studies (Lewis), and the definition of suitable design criteria and safety factors to ensure the structural integrity of the spacecraft STG.

The Group on Configurations and Aerodynamics recommended :

- Investigations to determine the effects of aerodynamic heating on control surfaces.

- Studies of the roll control maneuvers with center of gravity offset for range control.

- Tests of packaging and deployment of paraglider and multiple parachute landing systems.

- Studies to determine the effects of jet impingement upon the static and dynamic stability of the spacecraft.

- The General Electric Company effort was being concentrated on the Mark-ll, NERV, RVX (9 degree blunted cone), elliptical cone, half-cone, and Bell Aerospace Corporation Dyna-Soar types.

- The Martin Company was studying the M-1 and M-2 lifting bodies, the Mercury with control flap, the Hydrag (Avco Corporation), and a winged vehicle similar to Dyna-Soar. In addition, Martin was proposing to investigate the M-1-1, a lifting body halfway between the M-1 and the M- 2; a flat-bottomed lifting vehicle similar to the M-1-1 ; a lenticular shape; and modified flapped Mercury (the Langley L-2C).

- Convair/Astronautics Division of the General Dynamics Corporation had subcontracted the major effort on reentry to Avco, which was looking into five configurations: a Mercury-type capsule, the lenticular shape, the M-1, the flat-face cone, and half-cone.

- An "absolute emergency" navigation system in which the crew would use only a Land camera and a slide rule.

- The possible applications of the equipment and test programs to be used on Surveyor.

- The question whether Apollo lunar landing trajectories should be based on minimum fuel expenditure - if so, doubts were raised that the current STG concept would accomplish this goal.

- The question whether radio ranging could be used to reduce the accuracy requirements for celestial observations and whether such a composite system would fall within the limits set by the Apollo guidelines.

- The effects of lunar impact on the return spacecraft navigation equipment.

- Studies of hardware drift-error in the guidance and navigation systems and components.

- A study of the effect of rotating machinery aboard the spacecraft on attitude alignment and control requirements.

- Problems of planet tracking when the planetary disk was only partially illuminated.

- A study of the transient effects of guidance updating by external information.

- One adequate guidance and control concept to be mechanized and errors analyzed and evaluated.

- The effects of artificial g configurations on observation and guidance.

- The development of a ground display mission progress evaluation for an entire mission

- An abort guidance sequence including an abort decision computer and pilot display

- An earth orbit evaluation of the position computer input in a highly eccentric orbit (500- to 1000-mile perigee, 60,000-mile apogee).

1961 January 19 - .

- Studies of manned lunar and interplanetary expeditions - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. The Marshall Space Flight Center awarded contracts to the Douglas Aircraft Company and Chance Vought Corporation to study the launching of manned exploratory expeditions into lunar and interplanetary space from earth orbits..

1961 January 25 - .

- Study on the feasibility of refueling a spacecraft in orbit - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection, LM Mode Debate, LM Source Selection. NASA announced that the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation had been awarded a contract by the Marshall Space Flight Center to study the feasibility of refueling a spacecraft in orbit..

1961 January 31-February 1 - .

- Apollo feasibility study progress - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

Members of STG met with representatives of the Convair Astronautics Division of the General Dynamics Corporation and Avco Corporation to monitor the progress of the Apollo feasibility study. Configurations and aerodynamics and Apollo heating studies were discussed. Current plans indicated that final selection of their proposed spacecraft configuration would be made by Convair Astronautics within a week. The status of the spacecraft reentry studies was described by Avco specialists.

1961 February 7 - .

- MIT selected for a study of a navigation and guidance system for the Apollo spacecraft - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Guidance, CSM Source Selection. NASA selected the Instrumentation Laboratory of MIT for a six-month study of a navigation and guidance system for the Apollo spacecraft..

1961 March 20 - .

- STG met to plan general requirements for a proposal for advanced manned spacecraft development - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. Management personnel from NASA Headquarters and STG met to plan general requirements for a proposal for advanced manned spacecraft development..

1961 March 29-30 - .

- Convair selects M-1 design for Apollo in preference to lenticular configuration - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Heat Shield,

CSM Source Selection.

William W. Petynia of STG visited the Convair Astronautics Division of General Dynamics Corporation to monitor the Apollo feasibility study contract. A selection of the M-1 in preference to the lenticular configuration had been made by Convair. May 17 was set as the date for the final Convair presentation to NASA.

1961 April 10-12 - .

- Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Instrumentation and Communications drafted guidelines - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

The Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Instrumentation and Communications met at STG and drafted an informal set of guidelines and sent them to the other Technical Liaison Groups:

- Instrumentation requirements: all Groups should submit their requests for measurements to be made on the Apollo missions, including orbital, circumlunar, and lunar landing operations.

- Television: since full-rate, high-quality television for the missions would add a communications load that could swamp all others and add power and bandwidth requirements not otherwise needed, other Groups should restate their justification for television requirements.

- Temperature environment; heat normally pumped overboard might be made available for temperature control systems without excessive cost and complexity.

- Reentry communications; continuous reentry communications were not yet feasible and could not be guaranteed. It was suggested that all Groups plan their systems as though no communications would exist at altitudes between about 250,000 feet and 90,000 feet.

- Vehicle reentry and recovery: if tracking during reentry were desired, it would be far more economical to use a water landing site along the Atlantic Missile Range or another East Coast site.

- Digital computer : the onboard digital computer, if it were flexible enough, would permit the examination of telemetry data for bandwidth reduction before transmission.

- Antenna-pointing information: the spacecraft should have information relative to its orientation so that any high-gain directive antenna could be positioned toward the desired location on earth.

1961 April 10-12 - .

- Preparation of material for the Apollo spacecraft specification discussed - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

CSM Structural.

The Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Structures and Materials discussed at STG the preparation of material for the Apollo spacecraft specification. It decided that most of the items proposed for its study could not be specified at that time and also that many of the items did not fall within the structures and materials area. A number of general areas of concern were added to the work plan: heat protection, meteoroid protection, radiation effects, and vibration and acoustics.

1961 April 10-12 - .

- Second meeting of the Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Configurations and Aerodynamics at STG - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Parachute,

CSM Source Selection.

At the second meeting of the Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Configurations and Aerodynamics at STG, presentations were made on Apollo-related activities at the NASA Centers: heatshield tests (Ames Research Center); reentry configurations (Marshall Space Flight Center); reentry configurations, especially lenticular (modified) and spherically blunted, paraglider soft-landing system, dynamic stability tests, and heat transfer tests (Langley Research Center); tumbling entries in planetary atmospheres (Mars and Venus) (Jet Propulsion Laboratory); air launch technique for Dyna-Soar (Flight Research Center); and steerable parachute system and reentry spacecraft configuration (STG). Work began on the background material for the Apollo spacecraft specification.

1961 April 10-12 - .

- STG / Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Human Factors discussed Apollo spacecraft specification - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Cockpit,

CSM Source Selection.

At STG the Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Human Factors discussed the proposed outline for the spacecraft specification. Its recommendations included:

- NASA Headquarters Offices should contact appropriate committees and other representatives of the scientific community to elicit recommendations for scientific experiments aboard the orbiting laboratory to be designed as a mission module for use with the Apollo spacecraft.

- NASA should sponsor a conference of recognized scientists to suggest a realistic radiation dosage design limit for Apollo crews.

1961 April 10-13 - .

- Apollo spacecraft specification work - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

In preparing background material for the Apollo spacecraft specification at STG, the Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Mechanical Systems worked on environmental control systems, reaction control systems, auxiliary power supplies, landing and recovery systems, and space cabin sealing.

1961 April 10-12 - .

- Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Trajectory Analysis commented on Apollo specification - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Guidance,

CSM Source Selection.

The Apollo Technical Liaison Group for Trajectory Analysis met at STG and began preparing material for the Apollo spacecraft specification. It recommended:

- STG should take the initiative with NASA Headquarters in delegating responsibility for setting up and updating a uniform model of astronomical constants.

- The name of the Group should be changed to Mission Analysis to help clarify its purpose.

- A panel should be set up to determine the scientific experiments which could be done on board, or in conjunction with the orbiting laboratory, so that equipment, weight, volumes, laboratory characteristics, etc., might be specified

1961 April 25 - .

- Contract for the liquid-hydrogen liquid-oxygen fuel cell - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

A conference was held at Lewis Research Center between STG and Lewis representatives to discuss the research and development contract for the liquid-hydrogen liquid-oxygen fuel cell as the primary spacecraft electrical power source. Lewis had been provided funds approximately $300,000 by NASA Headquarters to negotiate a contract with Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Division of United Aircraft Corporation for the development of a fuel cell for the Apollo spacecraft. STG and Lewis representatives agreed that the research and development should be directed toward the liquid-hydrogen - liquid-oxygen fuel cell. Guidelines were provided by STG:

- Power output requirement for the Apollo spacecraft was estimated at two to three kilowatts.

- Nominal output voltage should be about 27.5 volts.

- Regulation should be within +/- 10 percent of nominal output voltage.

- The fuel cell should be capable of sustained operation at reduced output (10 percent of rated capacity, if possible).

- The fuel cell and associated system should be capable of operation in a space environment.

1961 May 5 - .

- First draft of the Apollo spacecraft specification - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

STG completed the first draft of "Project Apollo, Phase A, General Requirements for a Proposal for a Manned Space Vehicle and System" (Statement of Work), an early step toward the spacecraft specification. A circumlunar mission was the basis for planning.

1961 May 7 - .

- Initial Study Contracts - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Moon.

Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

In initial study contracts, Martin proposed vehicle similar to the Apollo configuration that would eventually fly and closest to STG concepts. GE proposed design that would lead directly to Soyuz. Convair proposed a lifting body concept. All bidders were influenced by STG mid-term review that complained that they were not paying enough attention to conical blunt-body CM as envisioned by STG.

1961 May 15 - .

- Final study contract reports. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Moon.

Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

The final reports on the feasibility study contracts for the advanced manned spacecraft were submitted to STG at Langley Field, Va., by the General Electric Company, Convair Astronautics Division of General Dynamics Corporation, and The Martin Company. These studies had begun in November 1960.

1961 May 18-31 - .

- Apollo A - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth.

Spacecraft Bus: Apollo CSM.

Spacecraft: Apollo A.

Space Task Group Director Robert R. Gilruth informed Ames Research Center that current planning for Apollo 'A' called for an adapter between the Saturn second stage and the Apollo spacecraft to include, as an integral part, a section to be used as an orbiting laboratory. Preliminary in-house configuration designs indicated this laboratory would be a cylindrical section about 3.9 m in diameter and 2.4 m in height. Additional Details: here....

1961 May 22 - .

- Second draft of the Apollo spacecraft specification - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. The second draft of a Statement of Work for the development of an advanced manned spacecraft was completed, incorporating results from NASA in-house and contractor feasibility studies..

1961 June 16 - .

- Fleming Committee Report: lunar mission could be accomplished within the decade - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Seamans.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection,

LM Mode Debate,

LM Source Selection.

The Fleming Committee, which had been appointed on May 2, submitted its report to NASA associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., on the feasibility of a manned lunar landing program. The Committee concluded that the lunar mission could be accomplished within the decade. Chief pacing items were the first stage of the launch vehicle and the facilities for testing and launching the booster. It also concluded that information on solar flare radiation and lunar surface characteristics should be obtained as soon as possible, since these factors would influence spacecraft design. Special mention was made of the need for a strong management organization.

1961 June - .

- Project Apollo feasibility studies assessed - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

STG completed a detailed assessment of the results of the Project Apollo feasibility studies submitted by the three study contractors: the General Electric Company, Convair/Astronautics Division of the General Dynamics Corporation, and The Martin Company. (Their findings were reflected in the Statement of Work sent to prospective bidders on the spacecraft contract on July 28.)

1961 July 18 - .

- NASA-Industry Apollo Technical Conference - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Moon.

Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

1,000 persons from 300 potential Project Apollo contractors and government agencies attended the conference. STG pushed the conical CM shape, in defiance of Gilruth's preference for the competitive blunt body/lifting body designs. Scientists from NASA, the General Electric Company, The Martin Company, and General Dynamics/Astronautics presented the results of studies on Apollo requirements. Within the next four to six weeks NASA was expected to draw up the final details and specifications for the Apollo spacecraft.

1961 July 28 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- NASA invitation to bids for Apollo prime contract - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Original Specification,

CSM Source Selection.

NASA invited 12 companies to submit prime contractor proposals for the Apollo spacecraft by October 9: The Boeing Airplane Company, Chance Vought Corporation, Douglas Aircraft Company, General Dynamics/Convair, the General Electric Company, Goodyear Aircraft Corporation, Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, The Martin Company, North American Aviation, Inc., and Republic Aviation Corporation. Additional Details: here....

1961 July 28 - .

- Source Evaluation Board to evaluate contractors' proposals for the Apollo spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Faget.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Source Selection.

NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., appointed members to the Source Evaluation Board to evaluate contractors' proposals for the Apollo spacecraft. Walter C. Williams of STG served as Chairman, and members included Robert O. Piland, Wesley L. Hjornevik, Maxime A. Faget, James A. Chamberlin, Charles W. Mathews, and Dave W. Lang, all of STG; George M. Low, Brooks C. Preacher, and James T. Koppenhaver (nonvoting member) from NASA Headquarters; and Oswald H. Lange from Marshall Space Flight Center. On November 2, Faget became the Chairman, Kenneth S. Kleinknecht was added as a member, and Williams was relieved from his assignment.

1961 July-September - .

- Work statements for the Apollo guidance and navigation system - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Guidance, CSM Source Selection. The MIT Instrumentation Laboratory and NASA completed the work statements for the Laboratory's program on the Apollo guidance and navigation system and the request for quotation for industrial support was prepared..

1961 July - .

- Polaris program experience studied for Apollo - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Guidance,

CSM Source Selection.

Ralph Ragan of the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, former director of the Polaris guidance and navigation program, in cooperation with Milton B. Trageser of the Laboratory and with Robert O. Piland, Robert C. Seamans, Jr., and Robert G. Chilton, all of NASA, had completed a study of what had been done on the Polaris program in concept and design of a guidance and navigation system and the documentation necessary for putting such a system into production on an extremely tight schedule. Using this study, the group worked out a rough schedule for a similar program on Apollo.

1961 August 7 - .

- Additional Panels evaluate proposals for the Apollo spacecraft - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Source Selection. STG appointed members to the Technical Subcommittee and to the Technical Assessment Panels for evaluation of industry proposals for the development of the Apollo spacecraft..

1961 August 9 - .

- First Apollo development contract - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Moon.

Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Guidance,

CSM Source Selection.

NASA selected MIT's Instrumentation Laboratory to develop the guidance-navigation system for Project Apollo spacecraft. This first major Apollo contract was required since guidance-navigation system is basic to overall Apollo mission. The Instrumentation Laboratory of MIT, a nonprofit organization headed by C. Stark Draper, has been involved in a variety of guidance and navigation systems developments for 20 years. This first major Apollo contract had a long lead-time, was basic to the overall Apollo mission, and would be directed by STG.

1961 August 14 - .

- Atmospheric requirement for the Apollo spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

STG requested that a program be undertaken by the U.S. Navy Air Crew Equipment Laboratory, Philadelphia, Penna., to validate the atmospheric composition requirement for the Apollo spacecraft. On November 7, the original experimental design was altered by the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC). The new objectives were:

- Establish the required preoxygenation time for a rapid decompression (80 seconds) from sea level to 35,000 feet.

- Discover the time needed for equilibrium (partial denitrogenation) at the proposed cabin atmosphere for protection in case of rapid decompression to 35,000 feet.