Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Apollo (ASTP)

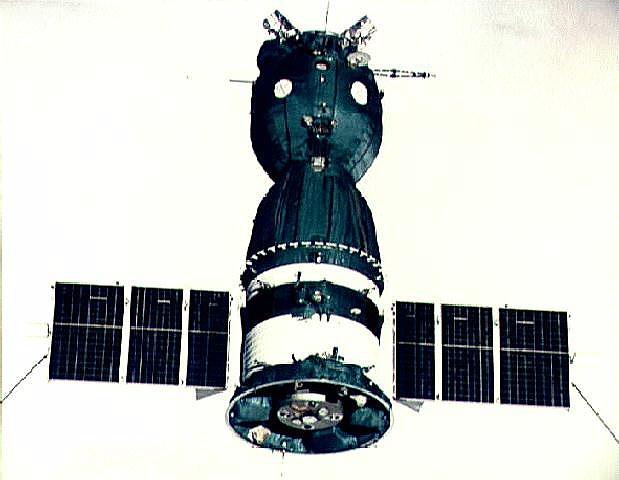

Soyuz ASTP in Orbit

Soyuz ASTP in Orbit 3

Credit: NASA

AKA: Apollo. Launched: 1975-07-15. Returned: 1975-07-24. Number crew: 3 . Duration: 9.06 days. Location: Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral, FL.

This flight marked the culmination of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, a post-moon race 'goodwill' flight to test a common docking system for space rescue. Meetings began in 1969 between Russian and American representatives on a joint manned space mission. Ambitious plans for use of Skylab or Salyut space stations were not approved. Instead it was decided to develop a universal docking system for space rescue. A working group was set up in October 1970 and in May 1972 the USA/USSR Agreement was signed with launch to take place in 1975. D Bushuev and G Lanin were the technical directors of the Soviet-designed EPAS docking system program. 1600 experiments were conducted in developing the system.

15 July 1975 began with the flawless launch of Soyuz 19. Apollo followed right on schedule. Despite a stowaway - a 'super Florida mosquito' - the crew accomplished a series of rendezvous maneuvers over the next day resulting in rendezvous with Soyuz 19. At 11:10 on 17 July the two spacecraft docked. The crew members rotated between the two spacecraft and conducted various mainly ceremonial activities. Stafford spent 7 hours, 10 minutes aboard Soyuz, Brand 6:30, and Slayton 1:35. Leonov was on the American side for 5 hours, 43 minutes, while Kubasov spent 4:57 in the command and docking modules.

After being docked for nearly 44 hours, Apollo and Soyuz parted for the first time and were station-keeping at a range of 50 meters. The Apollo crew placed its craft between Soyuz and the sun so that the diameter of the service module formed a disk which blocked out the sun. This artificial solar eclipse, as viewed from Soyuz, permitted photography of the solar corona. After this experiment Apollo moved towards Soyuz for the second docking.

Three hours later Apollo and Soyuz undocked for the second and final time. The spacecraft moved to a 40 m station-keeping distance so that the ultraviolet absorption (UVA MA-059) experiment could be performed. This was an effort to more precisely determine the quantities of atomic oxygen and atomic nitrogen existing at such altitudes. Apollo, flying out of plane around Soyuz, projected monochromatic laser-like beams of light to retro-reflectors mounted on Soyuz. On the 150-meter phase of the experiment, light from a Soyuz port led to a misalignment of the spectrometer, but on the 500-meter pass excellent data were received; on the 1,000-meter pass satisfactory results were also obtained.

With all the joint flight activities completed, the ships went on their separate ways. On 20 July the Apollo crew conducted earth observation, experiments in the multipurpose furnace (MA-010), extreme ultraviolet surveying (MA-083), crystal growth (MA-085), and helium glow (MA-088). On 21 July Soyuz 19 landed safely in Kazakhstan. Apollo continued in orbit on 22-23 July to conduct 23 independent experiments - including a Doppler tracking experiment (MA-089) and geodynamics experiment (MA-128) designed to verify which of two techniques would be best suited for studying plate tectonics from earth orbit.

After donning their space suits, the crew vented the command module tunnel and jettisoned the docking module. The docking module would continue on its way until it re-entered the earth's atmosphere and burned up in August 1975. Apollo splashed down about 7,300 meters from the recovery ship New Orleans. However the flight of the last Apollo spacecraft was marred by the fact that the crew almost perished while the capsule was descending under its parachute.

A failure in switchology led the automatic landing sequence to be not armed at the same time the reaction control system was still active. When the Apollo hadn't begun the parachute deployment sequence by 7,000 meters altitude, Brand hit the manual switches for the apex cover and the drogues. The manual deployment of the drogue chutes caused the CM to sway, and the reaction control system thrusters worked vigorously to counteract that motion. When the crew finally armed the automatic ELS 30 seconds later, the thruster action terminated.

During that 30 seconds, the cabin was flooded with a mixture of toxic unignited propellants from the thrusters. Prior to drogue deployment, the cabin pressure relief valve had opened automatically, and in addition to drawing in fresh air it also brought in unwanted gases being expelled from the roll thrusters located about 0.6 meter from the relief valve. Brand manually deployed the main parachutes at about 2,700 meters despite the gas fumes in the cabin.

By the time of splashdown, the crew was nearly unconscious from the fumes, Stafford managed to get an oxygen mask over Brand's face. He then began to come around. When the command module was upright in the water, Stafford opened the vent valve, and with the in-rush of air the remaining fumes disappeared. The crew ended up with a two-week hospital stay in Honolulu. For Slayton, it also meant the discovery of a small lesion on his left lung and an exploratory operation that indicated it was a non-malignant tumor.

Official NASA Account from: The Partnership: A History of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, by Edward Clinton Ezell and Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA History Series SP-4209, 1978.

15 July 1975 - Launch

The day began with the flawless launch of Soyuz 19. The initial orbital parameters were 220.8 by 185.07 kilometres, at the desired inclination of 51.80 deg , while the period of the first orbit was 88.6 minutes. There were smiles in Moscow and in Houston.

At the time of the Soyuz lift-off, liquid oxygen was flowing into the tanks of the Apollo launch vehicle at a fast fill rate of 4,543 litres per minute. After the USSR launch, Lee, Kapryan, and Scherer got a briefing on the predicted weather conditions for the afternoon - there were thunderstorms in the vicinity of the Cape, but they were not expected to affect the American lift-off. In Houston, Lunney called Professor Bushuyev to congratulate him on the success of the Soyuz launch and to advise him that the countdown was proceeding on schedule with the best weather forecast in months. Bushuyev reported in turn that the orbit of Soyuz was within 2 or 3 kilometres of the desired figures.

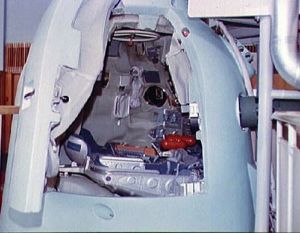

Stafford, Slayton, and Brand were awakened at 9:10. Following their visit with the doctors, the astronauts sat down to the traditional pre-flight breakfast of steak and scrambled eggs. Robert Crippen, the Backup Command Module Pilot, meanwhile began the final preparation of the command and service module (CSM) cockpit in anticipation of the crew's arrival. Once they completed their breakfast, the three men went to the suit room in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building and donned their space suits. At 11:37, accompanied by John Young, Chief of the Astronaut Office, they rode down the elevator and boarded their van for the 25-minute ride to the launch pad.

With the assistance of their suit technicians, the crew arrived at Pad 39B, where they made their way by elevator to the 100-meter level of the mobile launch tower. Stafford was the first into the cockpit, where he moved into the left couch, assisted from the inside by Crippen, who also connected Stafford's electrical, oxygen, and communications umbilicals. Slayton was next, and Crippen went through the same procedures after he was seated in the right-hand couch. Brand was last. When Crippen completed his check of Brand's fittings, he removed the protective covering from the crewman's helmet, as he had for the other two. At 12:02, Stafford called to the test conductor Clarence Chauvin, "Looks like it's a good day to fly."

Crippen slid down under the centre couch and crawled out the hatch above Brand's head. After some additional checks, the CSM hatch was closed at approximately 12:22. As the first live launch pad colour television pictures of the interior of the CSM were broadcast to the world, the crew began to run through the final checklist. Stafford asked Karol "Bo" Bobko, the Spacecraft Communicator (CapCom) at 1.10, "Are you giving us the countdown in English or Russian today?" Bobko responded, "Oh, I figured I'd give it in English." In Moscow, the Soviet flight director was reminding Leonov and Kubasov that the Apollo lift-off was set for 10:50 Moscow time (2:50 CDT). At T minus 7 minutes, 52 seconds, the Apollo crew members finished their checkout of some 556 switches, 40 event indicators, and 71 lights on the console. Stafford told Bobko to tell Soyuz to get ready for them. "We'll be up there shortly."

After the final minutes of waiting, at 2:49:50, the now famous count backwards from 10 began. "10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, engine sequence start, 1, 0, launch. . . . We have lift-off. Moving out, clear the tower." Above the roar of the first-stage engines, Stafford reported that the ride had been a little shaky at lift-off, but now it was "smooth as silk." Fifty seconds into the flight, the acceleration force equalled 2 Gs, twice the gravitational force normally experienced on earth. At 124 seconds, the crewmen were experiencing 4 Gs as they dropped off the first stage and continued their journey under the power of the S-IVB stage. Fifty-two seconds later, they jettisoned the launch escape tower, and Stafford remarked, "Tower jett. There she goes! . . . Adios. . . . At 4:40, back to one g acceleration and looking good."

Dick Truly, CapCom: Apollo, Houston. At 5 minutes you're GO.

Stafford: Roger. 5 minutes. Looks good onboard, Dick. And we've got a beautiful sight.

Truly: Roger. Wish I could see it.

Stafford: Roger.

Slayton: Man, I tell you, this is worth waiting 16 years for.

Brand: Got a beautiful ocean out . . . here, Dick.

Truly: Roger, I believe all that.

Stafford: Okay, at 5:30, onboard trajectory looks beautiful.

Truly: Roger. Concur, Tom. You're right on the money.

On the ground, Ed Smith and R. H. Dietz with grins on their faces echoed the same thoughts when they said, "We've got a ball game!" The rendezvous chase was on. Apollo had achieved orbital insertion at 2:59:55.5 central daylight time. Brand exclaimed, "Miy nakhoditsya na orbite!"

Stafford notified Houston at 3:55 p.m. that the crew was preparing to execute the transposition, docking, and extraction manoeuvre in 2 minutes. As a preliminary to removing the docking module (DM) from the spacecraft lunar module adapter (SLA) truss assembly, the CSM was separated from the S-IVB stage, and as the CSM moved away from the adapter section, the panels of the SLA were explosively jettisoned. In bringing the spacecraft about to face the docking module, the crew encountered its first minor problem of the flight. When Stafford looked through his alignment sight (COAS) at the Saturn IVB and docking module, the attitude was such that all he could see was the glare from the sunlit earth. At first he thought that the light illuminating the cross hairs in his sight had burned out. But when he put his hand in front of the COAS, Stafford reported that he could see the green reticule. Swearing under his breath, he knew that he would just have to wait until the two craft were positioned differently. Stafford moved the CSM toward the S-IVB and docking module until about only 10 meters separated them. Watching the stand-off cross on the docking module truss in the S-IVB stage, the Apollo crew assumed a station-keeping status. Slowly the target vehicle appeared to move toward the earth's horizon. Stafford squinted and leaned his head to one side so he could see the reticule. "Finally when I got it in line," he later recounted, "I could just tell my general attitude and moved in." Despite the problems, Stafford's docking was perfect. He had aligned the two spacecraft to within a hundredth of a degree, the best alignment ever achieved with the Apollo docking system. By the time he had lined up his target, Apollo had passed out of radio contact with the ground.

When Apollo re-established communications over Rosman, North Carolina, Stafford told Truly that they had achieved a real hard docking with the DM; all hatches were locked. The commander was happy to have this first docking completed. He later recalled that given the past problems with the Apollo probe and drogue, he had really been "sweating out" this exercise. Once it was over, he looked forward to meeting Soyuz. The new docking mechanism was a pilot's dream, and he knew that he could fly it in for a smooth docking.

During a subsequent 5-minute pass over the tracking ship USNS Vanguard, the crew members advised Houston that they had completed the extraction of the docking module. The spacecraft, configured as it would be for the meeting with the Soviet craft, was now in an orbit 173.3 by 154.7 kilometres with an orbital period of 87 minutes, 39 seconds, and an orbital velocity of 7,820 meters per second. Additional manoeuvres would bring Apollo and Soyuz into the proper orbital relationship for rendezvous. Apollo's orbit was circularised at 167.4 by 164.7 kilometres at 6:35. From this orbit, the first Apollo phasing manoeuvre was executed at 8:28 to provide the proper catch-up rate, so that docking with Soyuz could occur on the 36th Soviet revolution. This 20.5-meter-per-second change placed Apollo in a 233- by 169-kilometre path. The next phase and plane correction manoeuvre of 2.7 meters per second was scheduled for the 16th revolution.

In the midst of this precision flying, there were some lighter moments. At 6:10, Brand asked Truly to tell the launch crew at the Cape that they permitted a stowaway to board the spacecraft. "We found a super Florida mosquito flying around here a few minutes ago." Slayton said that he planned to feed it to the fish that they were carrying onboard if he could catch it, and Brand wanted to bring it back and give it astronaut wings. These transmissions were conducted through the ATS 6 satellite. While that particular communications satellite had been an unknown quantity throughout much of the mission planning, it was working very satisfactorily.

Later in the evening, after a cabin overheating problem had been solved, Brand asked Karol Bobko, who had relieved Truly as CapCom, about the status of Soyuz. Bobko reported that Leonov and Kubasov were asleep and that to this point in the flight their only problem was a television camera that refused to work. He told Vance that they had tried without success to repair it but they planned to work on it some more after their sleep period. Apollo meal time arrived at 10:06, and Slayton coined a new space phrase for eating when he indicated to Houston that he and his crew mates were in the "food intake mode."

A problem later that night, however, caused some concern both on the ground and in the spacecraft. Bobko had wished the crew good night in Russian, and they were supposed to be bedding down for a rest period, when at 22 minutes past midnight Stafford called to the ground. Brand had attempted to remove the probe assembly from the tunnel between the CSM and the DM so that he could open the hatch and store overnight a freezer in the passageway, but he found that he could not insert the tool that unlocked and collapsed the probe. Brand went on to explain the difficulty:

Brand: "Okay, Bo. Everything in the probe removal checklist on the cue card . . . has been going great up through step 11. Step 12 is "Capture latch release, tool 7." You insert it in the pyro cover. You turn it 180 degrees clockwise to release the capture latches. Well, here's where the problem is, and let me explain it to you. . . . do you have somebody there that knows the probe that can listen?"

Bobko: "Roger. Go ahead."

Brand: "Okay, as I look in the back of the . . . pyro cover, I'm looking with my flashlight through the hole where I insert this tool, and there's something behind the pyro cover that's preventing me from putting this tool all the way in. . . . it's actually one of the pyro connectors. . . . this tool has to go down through the pyro cover in between . . . some pyro connectors. But one of these pyro connectors has rotated such that it's in the way. . . ."

Neil B. Hutchinson, flight director at the time the probe problem was discovered, later told press representatives that the ground team and the crew had discussed the difficulty for about 18 minutes. Their first decision had been to forget transferring the freezer into the tunnel and just have the crew close the hatch and go to sleep. But when Brand tried to close the hatch, he discovered that the partially removed probe assembly prevented him from doing so. Since the three men were already past their sleep time and the open hatch did not pose a hazard, the two teams ground and space agreed to postpone any further work on the probe until morning. As a precaution, the crew raised by a very slight amount the cabin pressure, which provided additional oxygen to compensate for the nitrogen that was boiling off the freezer. The crew went to sleep.

16 July - Chase

As the Soyuz crew members prepared for the circularisation manoeuvre that would bring their spacecraft into a 225- by 225-kilometre orbit, the Apollo crew was awakened to the rock sounds of Chicago's "Good Morning Sunshine."

Medical reports and breakfast filled the first minutes of the Apollo crew's morning activities. With the exception of some minor frustrations like the slow functioning urine dump system and some spilled strawberry juice, everything was proceeding satisfactorily. Truly replaced Crippen and gave Brand the latest information on how to remove the probe.

Stafford came back on the air-to-ground communications loop at 9:55 a.m. to tell Houston that the probe was out. With that "glitch" solved, the crew members could return their attention to the flight plan. Preparation for televising pictures from the cabin and checking out the docking module were the next activities on the list. As they worked through their schedule, the Soviet crew members were transmitting their first television pictures with their colour camera.

Aboard Apollo, Stafford, Slayton, and Brand were settling into the routine of flight. Their day was filled with independent experiments (electrophoresis, helium glow, and earth observation) and collecting biomedical data. During the earth observation pass, Stafford told Bobko to inform Farouk El-Baz, the principal investigator for that experiment, that at ASTP altitude one could see far more detail than in Project Gemini, where Stafford and Cernan had flown at a higher altitude (+60 kilometres). The crew made another course change at 3:18 p.m. In anticipation of their big day on the 17th, the Apollo team bedded down a few minutes after eight, and the Soviet crew had been resting since about 2:50 that afternoon.

17 July - Rendezvous

Roused at 3:07 a.m. by an alarm and warning signal from the guidance system, the crew members decided to stay awake after determining that the warning was a false alarm. That morning Slayton observed a grass fire in Africa, and Stafford saw a forest fire atop a mountain in the USSR. Slayton commented that things looked just the same as in an airplane at 12,000 meters. At 7:56, 5 minutes after completing another manoeuvre to bring the craft into better attitude for rendezvous, the Apollo crew attempted radio contact with Soyuz. Brand reported at 8:00 that he had sighted Soyuz in his sextant. "He's just a speck right now."

Voice contact between the two ships was established 5 minutes later. Speaking in Russian, Slayton called, "Soyuz, Apollo. How do you read me?" Kubasov answered in English, "Very well. Hello everybody."

Slayton: Hello, Valeriy. How are you. Good day, Valeriy.

Kubasov: How are you? Good day.

Slayton: Excellent. . . . I'm very happy. Good morning.

Leonov: Apollo, Soyuz. How do you read me?

Slayton: Alexey, I hear you excellently. How do you read me?

Leonov: I read you loud and clear.

Slayton: Good.

Thirty-two minutes later at Slayton's signal, Kubasov turned on the range tone transfer assembly to establish ranging between the ships. The gap had been reduced to 222 kilometres. At 9:12, Apollo had changed its path again when the crew executed a co-elliptic manoeuvre that sent the craft into a 210- by 209-kilometre orbit. Apollo was spiralling outward relative to the earth to overtake the Soviet ship.

A 0.9-second terminal phase engine burn at 10:17 brought Apollo within 35 kilometres, and the crew began to slow the spacecraft as it continued on the circular orbit that would intersect that of the Soyuz. CapCom Truly advised Stafford at 10:46, "I've got two messages for you: Moscow is go for docking; Houston is go for docking, it's up to you guys. Have fun." Immediately, Stafford called out to Leonov, "Half a mile, Alexey." Leonov replied. "Roger, 800 meters." In accordance with the flight plan, the Soyuz crew had moved back into the descent vehicle and closed the hatch between them and the orbital module. Inside Apollo, the men had closed the CSM and DM hatches preparatory to docking. At a command from Stafford, Leonov performed a 60 deg roll manoeuvre to give Soyuz the proper orientation relative to Apollo for the final approach. On the television monitors in Houston and Moscow, Soyuz was seen as a brilliant green against the deep black of space as the onboard camera recorded the final approach.

Visitors in the MOCR viewing room for the docking included Captain Jacques Cousteau and Ambassador Anatoliy Fedorovich Dobrynin.

Leonov called out as the two ships came together. "Tom, please don't forget about your engine." This reference to the -X thrusters made Stafford and many of those on the ground who knew the story chuckle. Stafford called out the range, "less than five meters distance. Three meters. One meter. Contact." The hydraulic attenuators absorbed the force of the impact, and Leonov called out, "We have capture, . . . okay, Soyuz and Apollo are shaking hands now." It was 11:10 in Houston. Stafford retracted the guide ring, actuated the structural latches, and compressed the seals. In Russian he said, "Tell Professor Bushuyev it was a soft docking." "Well done, Tom," congratulated Leonov, "It was a good show. We're looking forward now to shaking hands with you on . . . board Soyuz."

The chase of Soyuz by Apollo had ended in a flawless docking. Stafford later recalled, "Later that night, we checked the alignment and noticed that the centre of the COAS was sitting right on the centre of a bolt that held the centre of the target in for Soyuz." That is dead centre.

Stafford and Slayton entered the docking module and closed behind them the hatch (no. 2) leading to the CSM. They raised the pressure from 255 to 490 millimetres by adding nitrogen to the previously 78 percent oxygen atmosphere. In Soyuz, the crew had reduced the cabin pressure to 500 millimetres before the docking. The pressure in the tunnel between the docking module hatch (no. 3) and the Soyuz hatch (no. 4) had been raised from zero to equal that of the docking module. Leonov and Kubasov were the first to open the hatch leading to the international greeting. During the transfer that was to follow, the pressure in the DM and Soyuz would be the same - 510 millimetres.

Then at 2:17:26 p.m. on the 17th of July, Stafford opened hatch number no. 3, which led into the Soyuz orbital module. With applause from the control centres in the background, Stafford looked into the Soviet craft and, seeing all their umbilicals and communications cables floating about, said, "Looks like they['ve] got a few snakes in there, too." Then he called out, "Alexey. Our viewers are here. Come over here, please." High above the French city of Metz, the two commanders shook hands. In the background was a hand-lettered sign in English - "Welcome aboard Soyuz."

When they talked later with President Ford, the crews were taken by surprise when the President talked for 9 minutes instead of the scheduled 5. He asked a barrage of questions that sent the crews scrambling to trade off their three flight helmets to they could respond to him.

Next Stafford, Slayton, Leonov, and Kubasov made a symbolic exchange of gifts, while Brand remained in the command module monitoring the American craft and waiting for his turn to visit Soyuz. The four men settled down to their first joint space banquet.

Stafford and Slayton said good-bye to Leonov and Kubasov at 5:47 and floated back through the tunnel into the docking module. Stafford returned to the command module, while Slayton closed the DM hatch. In Soyuz, the Soviets were securing their hatch, also. During the ensuing pressure integrity check, a possible leak through hatch nos. 3 or 4 was detected by the Soyuz monitoring equipment. This apparent flow of gas between the two hatches, while not serious, caused the crews to get to sleep a little later than planned. Finally, by 7:36, the Apollo crewmen had bid the ground good night and were beginning to settle down.

18 July - Transfers

Awakened by "Midnight in Moscow," the Americans began their fourth work day in orbit at 2:00 a.m. Houston time. While the crews had slept, the two ground teams in Houston led by Walt Guy and V. K. Novikov had been watching the pressure levels of both ships and had conferred about the leak between the hatches. They had concluded that after the two hatches were closed and the pressure had been reduced to 260 millimetres the gases trapped between them heated up..

With breakfast behind them and their early morning activities completed, Kubasov and Brand conducted a broadcast session from "your Soviet American TV centre in space," as Kubasov called it. In giving his tour of Soyuz, the Soviet flight engineer pointed out what various instruments were for and televised a picture of Brand in "the kitchen" (the food preparation station) warming up lunch. Stafford reciprocated by giving Leonov and the Soviet viewers a Russian language tour of the command module. Appearing casually simple from the perspective of the home viewer, these broadcasts had required hours of negotiation and planning, just as all other aspects of the flight had.

Kubasov later gave an English language travelogue as the two craft passed over the USSR. At about 8:20, Brand and Kubasov began filming some science demonstrations that could later be used in science classrooms back on earth to demonstrate the effects of zero gravity on various items. During this second transfer, Brand had lunched in Soyuz and Leonov in Apollo. At 10:43, Brand returned to Apollo, and Stafford and Leonov moved into Soyuz. Kubasov then transferred into the command module in this exacting cosmic ballet. With each movement of the crew members, the atmospheric composition of Soyuz had to be checked to make certain that not too much nitrogen had been removed. Once everyone was in place, the hatches between the orbital and docking modules were closed as a further step toward maintaining the proper cabin atmospheres. The highlight of the third transfer - was a space-to-ground press conference. The best lines came when asked how he liked the American food, Leonov diplomatically answered, "I liked the way it was prepared, its freshness."

The crews returned to other items on their flight plan. Slayton, as part of the earth observation experiment (MA-136), took photos of ocean currents off the Yucatan Peninsula and in the Florida straits. Slayton, Brand, and Kubasov assembled the two halves of a medallion commemorating the flight, and then they exchanged tree seeds.

Tom Stafford shook hands with Leonov and Kubasov, bidding them farewell at about 3:49 in the afternoon. He then moved back into the docking module, and the space men closed the hatches for the last time at 4:00. The records indicated that Stafford spent 7 hours, 10 minutes aboard Soyuz, Brand 6:30, and Slayton 1:35. Leonov was on the American side for 5 hours, 43 minutes, while Kubasov spent 4:57 in the command and docking modules.

Although the crew signed off for the evening on schedule at 7:20, they spent an uneasy first few hours. In addition to being very tired from the activities of their fourth day in space, they were jangled awake an hour later by a master alarm that reported a reduction in docking module oxygen pressure. This problem was no real hazard, and it was quickly solved by an increased flow of oxygen into the DM, but it kept the crew from getting all the sleep for which they had been scheduled. When wake-up time came at 3:13 on the morning of the 19th, the crew failed to hear the musical strains of "Tenderness" as sung by the Soviet female artist Maya Kristalinskaya, with which the ground team had hoped to gently waken them. But 15 minutes later, they were awake and ready to begin their fifth day. Next door, beyond hatches three and four, Leonov and Kubasov were getting prepared, too.

19 July - Exercises

During day five of the flight, the crews concentrated on docking exercises and experiments that involved the two ships in the undocked mode. During the interval between the first undocking and the second docking, the Apollo crew placed its craft between Soyuz and the sun so that the diameter of the service module formed a disk which blocked out the sun. This artificial solar eclipse, as viewed from Soyuz, permitted Leonov and Kubasov to photograph the solar corona. Ground-based observations were conducted simultaneously, so that the Soviet astronomer G. M. Nikolsky could compare views of the solar phenomena with and without the interference of the earth's atmosphere. Skylab had provided a long term look at the corona, and the ASTP data would give scientists an opportunity to compare findings made a year and a half later.

Another major experiment, "ultraviolet absorption" (MA-059), was an effort to more precisely determine the quantities of atomic oxygen and atomic nitrogen existing at such altitudes as the one in which Apollo and Soyuz were orbiting. Again this information could not readily be obtained from ground-based observations because of the intervening layers of atmosphere. Apollo, flying out of plane around Soyuz, first at 150 meters, then at 500 meters, and finally in plane at 1,000 meters, projected monochromatic laser-like beams of light to retro-reflectors mounted on Soyuz. When the beams were reflected back to Apollo, they were received by a spectrometer, which recorded the wavelength of the light. Subsequent analysis of these data would yield information on the quantities of oxygen and nitrogen. Some very precise flying was called for in these experiments.

After being docked for nearly 44 hours, Apollo and Soyuz had parted for the first time at 7:12 a.m. while out of contact with the ground. Slayton advised Bobko after radio contact was re-established that they had undocked without incident and were station-keeping at a range of 50 meters. Meanwhile, Soyuz had extended the guide ring on its docking system in order to test the Soviet mechanism in the active configuration. Once they completed the solar eclipse experiment, with Slayton at the controls, Apollo moved towards Soyuz for the second docking. As he did, Stafford called out to the ground, "Okay, Houston, Deke's having the same problem with the COAS washout that I had." As Slayton explained it, he could see Soyuz and the target initially when they were against the dark sky, but at "about 100 meters or so, it went against the earth background and zap. Man, I didn't have anything." Although worried that he might run over Soyuz, he pressed on with the docking "by the seat of the pants and I guess I got a little closer than they or the ground anticipated." There was too much light flowing into the optical alignment sight for Slayton to get a good view of the docking target. Contact with Soyuz came at 7:33:39, and Leonov advised the Americans that he was beginning to retract his side of the docking assembly.

As viewed via Apollo television, this docking looked as if it had been harder than the first, and the two ships continued to sway after capture had been completed. Slayton, speaking in a debriefing, later said:

The docking was normal, you guys gave me contact as usual and then I gave it thrusting. The only thing that happened then was they seemed to torque off. I was surprised at the angle they banged off there after we had contact.

Despite this oscillation, the Soyuz system aligned the two craft and a proper retraction was completed. Subsequently, there was some discussion of this docking, and the Soviet docking specialist Syromyatnikov was at first worried that an unnecessary strain might have been placed on the Soyuz gear. Bob White said that analysis of the telemetry data indicated that Slayton had inadvertently fired the roll thrusters for approximately 3 seconds after contact, and that this sideways force caused the craft to oscillate after the docking systems were locked and rigid.

But even with the extra thrusting, the second docking was within the limits of safety established for the docking system. Slayton's docking took place at a forward velocity of 0.18 meter per second versus 0.25 meter per second for Stafford's docking, but the difference lay in the inadvertent thrusting. Momentarily an issue, the extra motion of Slayton's try was not a serious concern after all the data had been evaluated. Even Syromyatnikov had to concede that "the mechanism functioned well under unfavourable conditions." It was a case of things looking worse than they really were. In the end, the incident only demonstrated the reliability and hardiness of the new docking system.

It was 10:27 when Apollo and Soyuz undocked for the second and final time. This 4-minute exercise was conducted by Leonov, since it was a Soyuz active undocking. Slayton then moved his ship to a station-keeping distance, about 40 meters away. As he did, Leonov opened the retro-reflector covers so that the ultraviolet absorption (UVA) experiment could be performed. A difficult series of manoeuvres were called for in this test. As Soyuz continued its circular orbit, Slayton took Apollo out of plane with Soyuz and oriented his craft so that its nose was pointed at the reflector on the side of the other ship. Orbiting sideways in this configuration, Slayton flew Apollo in a small arc from the front of Soyuz to the rear of that ship while the spectrometer gathered the reflected beams. On the 150-meter phase of the experiment, light from a Soyuz port led to a misalignment of the spectrometer, but on the 500-meter pass excellent data were received; on the 1,000-meter pass satisfactory results were also obtained.

After nearly 3 hours of tough flying, Bobko congratulated the crew. "You people flew it fine." Slayton responded:

Okay. Great, Bo. And you can thank ol' Roger Burke, Steve Grega, and Bob Anderson, down there, that everything came off right. 'Cause they sure did all the work to make it go.

The three men Slayton mentioned had spent hours in the simulators working out the procedures to fly this complicated manoeuvre. Burke, who had worked with developing flight procedures for years, felt that this was one of the hardest experiments a crew had ever been called on to do, especially since the flight plan for it had continued to evolve until a couple of days before launch. Slayton later noted that it had taken all three Apollo crewmen to complete the ultraviolet absorption experiment. "I was doing the flying, Vance was running the computer and we had Tom down in the equipment bay opening and closing doors, turning on sensors and so forth. So, it was a busy time for all of us." He indicated that the manoeuvres were difficult because orbital mechanics came into play as they tried to fly around Soyuz. When the Apollo crew changed the velocity of their craft, they also affected its orbit. They would have no difficulties if they had had unlimited fuel resources, but being out of plane and playing orbital mechanics with "a very limited fuel budget . . . made it a great challenge." Stafford added that the thruster firings had to be timed because the onboard accelerometers could not measure the changes in velocity.

Apollo performed a separation manoeuvre at 1:42 to prevent re-contact with Soyuz, placing the American craft in a 217- by 219-kilometre orbit. With all the joint flight activities completed, the ships were going their separate ways. Soyuz was below and moving ahead of Apollo at a rate of 6 to 8 kilometres per orbit. Leonov and Kubasov prepared to go to sleep, but the American crew had several hours of work scheduled in their crowded flight plan after their mid-afternoon meal before they could settle down for a rest period.

20 July - Independent Activities

Houston control tried for a second morning to wake the crew with "Tenderness" in Russian. This time they succeeded, and the men began their sixth day at 1:54 a.m. In addition to a day-long earth observation, which they started before breakfast, they concentrated on experiments during their first independent day in orbit. Included in the flight plan were experiments in the multipurpose furnace (MA-010), extreme ultraviolet surveying (MA-083), crystal growth (MA-085), and helium glow (MA-088). In the midst of their work during an ATS 6 communication session, CapCom Crippen gave them a news report.

Crippen included a special item in his report. "Six years ago today at 3:17:40 central daylight time we landed on the Moon. At 9:56, that's when Neil said his famous words about 'small step for man, giant leap for mankind.' " Stafford responded, "Roger. Remember it well."

Slayton: Say, what day of the week is this, incidentally?

Crippen: This happens to be Sunday.

Brand: [garbled] . . . our day off.

Crippen: Oh, yeah. We'll get them off after you guys get back. Y'all . . are certainly not getting a day off today.

Brand: We're not complaining.

While there was still much to do, the pressure of the first days of the mission was gone, and the crew was settling down to the routine. The sixth day of the ASTP flight was noticeably void of the drama that had been associated with the joint activity.

21 July - Farewell

Following a rest period of nearly 10 hours, the Soyuz crewmen advised the ground that they were awake and that all systems were normal. The deorbit burn came exactly on time (5:09 in Houston), and the Soyuz crew landed safely in Kazakhstan. For the remaining three and a half days, Stafford, Slayton, and Brand would concentrate on their experiments, but in many respects the saga of Apollo and Soyuz had come to an end.

22-23 July - Experiments

Some minor experiment hardware problems developed during the final days of the mission, but for the most part the crew members worked through their flight plan - which included 23 independent experiments - with few difficulties. After a relatively quiet day of work on the 22nd, the major part of the next day was devoted to preparing for and conducting the doppler tracking experiment (MA-089). Paired with the geodynamics experiment (MA-128), these investigations were designed to verify which of two techniques would be best suited for studying plate tectonics (movements of the earth's substrata) from earth orbit. Where the geodynamics experiment utilised Apollo and ATS 6 in an attempt to measure these movements (the so-called low-high approach), the doppler tracking experiment involved the use of two satellites in low earth orbit (the low-low approach) to measure the existence of "mass anomalies" greater than 200 kilometres in size. When the jettisoned docking module and the CSM were separated by 300 kilometres, they would theoretically have their orbits affected by the greater gravitational forces exerted by these mass anomalies. As their orbits were perturbed, the radio signals transmitted from one to another would correspondingly be affected.

Prior to releasing the docking module on its separate journey, the crew had participated in a second press conference from space. Deke Slayton's statement that he had done nothing in space that his 91-year old aunt could not have done sent reporters scrambling to find out her name (Mrs. Sadie Link) so they could meet their deadlines. After donning their space suits, the crew vented the command module tunnel and at 2:41 jettisoned the docking module. Filled with all their trash and used equipment that need not be returned, the DM tumbled into space at exactly the proper rate. Stafford and his team then executed their separation manoeuvre so that they could take the necessary doppler measurements. The docking module would continue on its way until it re-entered the earth's atmosphere and burned up in August 1975.

24 July - Last Splash

Approximately 24 hours after they parted from the docking module, Stafford, Slayton, and Brand began their journey homeward. On the ground, the flight control team played Jerry Jeff Walker's "Redneck Mother" to wake the crew. With a cheery "Good morning, gents. Party's over. Time to come home," CapCom Crippen told them to rise and shine. At half past seven, the crew started preparing for its mid-afternoon deorbit. As the men rubbed the sleep from their eyes, ate breakfast, and gathered data for the medical doctors on the ground, Crippen read them the news for the last time. Crippen gave a favourable weather forecast for the prime recovery area - visibility 16 kilometres, winds at 17 knots, scattered cloud cover at 600 meters, and wave height 1.1 meters.

CSM deorbit came at 3:37:47, or about 13 seconds ahead of schedule. Six and a half minutes later, the command module was separated from the service module. As the re-entry vehicle descended, Slayton and Brand commented on the build-up of gravity forces and the fireball that flared up as the heat shield pressed against the earth's atmosphere. At 4:18:24, Apollo splashed down about 7,300 meters from the recovery ship New Orleans. Houston control was filled with smiling faces and cigar smoke. Unknown at that time to the celebrants was the fact that the crew had inhaled nitrogen tetroxide fumes during the descent.

The descent phase had gone without incident until about 15,000 meters. In the days that followed the recovery, the story of the failure to actuate the Earth landing system (ELS) was told and retold several times by Glynn Lunney, John Young, and others. Vance Brand presented his version during the crew technical debriefing. When the CM reached an altitude of 9,144 meters, two earth landing switches that permitted the apex cover to be jettisoned at 7,310 meters were normally armed. The drogue parachutes would then be released, followed by the main chutes. Commenting on the descent, Brand said that as Stafford read steps from the Entry Checklist he threw the proper switches. There was quite a bit of noise in the cabin from the command module's thrusters and the passage of the craft through the atmosphere.

At 30K [9,144 meters], normally we arm the ELS AUTO, ELS LOGIC, that didn't get done. Probably due to a combination of circumstances. I didn't hear it called out, maybe it wasn't called out. Any case 30K to 24K [9,144-7,315 meters] we passed through that regime very quickly. I looked at the altimeter at 24K, and didn't see the expected apex cover come off. Didn't see the drogues come out. So, I think at about 23K, I hit the two manual switches. One for the apex cover and also, the one for drogues. They came out. That same instant the cabin seemed to flood with a noxious gas, very high concentration it seemed to us. Tom said he could see it. I don't remember for sure now, if I was seeing it, but I certainly knew it was there. I was feeling it and smelling it. It irritated the skin a little bit, and the eyes a little bit, and, of course, you could smell it. We started coughing. About that time, we armed the automatic system, the ELS. . . .

The manual deployment of the drogue chutes caused the CM to sway, and the reaction control system thrusters worked vigorously to counteract that motion. When the crew finally armed the automatic ELS 30 seconds later, the thruster action terminated.

During that 30 seconds, the cabin was flooded with a mixture of unignited propellant and oxidisers from the thrusters. Prior to drogue deployment, the cabin pressure relief valve had opened automatically, and in addition to drawing in fresh air it also brought in unwanted gases being expelled from the roll thrusters located about 0.6 meter from the relief valve. Brand manually deployed the main parachutes at about 2,700 meters, and despite the gas fumes in the cabin, the crew members continued to work through their checklist as best they could. Due to severe coughing and intercom noise, they had difficulty talking to one another and to the ground.

Following a normal but hard splashdown, the command module flipped over, leaving the three men hanging upside down in their couches from harnesses. Brand, who was coughing the most because he was closest to the steam duct opening, saw that Slayton was feeling nauseous and reminded Stafford to get their oxygen masks. The commander recalled:

For some reason, I was more tolerant to [the bad atmosphere], and I just thought get those damn masks. I said don't fall down into the tunnel. I came loose and . . . had to crawl . . . and bend over to get the masks. . . . l knew that I had a toxic hypoxia . . . and I started to grunt-breathe to make sure I got pressure in my lungs to keep my head clear. I looked over at Vance and he was just hanging in his straps. He was unconscious.

After Stafford secured the oxygen mask over Brand's face and held it there, he began to come around. Once the entire crew was breathing pure oxygen, Brand actuated the uprighting system. When the command module was upright in the water, Stafford opened the vent valve, and with the in-rush of air the remaining fumes disappeared.

Failure to throw the ELS switches led to an unanticipated two-week hospital stay for the crew in Honolulu. For Slayton, it also meant the discovery of a small lesion on his left lung and an exploratory operation that indicated it was a non-malignant tumour. After a short convalescence, Slayton joined the other four ASTP flyers for two tours, one of the Soviet Union and one of the United States. Despite a gruelling month on the road, neither Slayton nor his team mates seemed any the worse for wear, and the warm public reception wherever they went seemed to indicate that the unfortunate accident at the end of the flight had not detracted from the basic success of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Rivalry had produced the first manned space flights in the early 1960s. But that sense of conflict had been overcome with the creation of an international test project. Ironically, this first joint flight also marked the end of an era. NASA's manned space program had seen its last splashdown. Apollo would fly no more.

More at: Apollo (ASTP).

Family: Manned spaceflight. People: Brand, Slayton, Stafford. Country: USA. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM. Projects: ASTP. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral. Agency: NASA Houston.

| Apollo (ASTP) Credit: www.spacefacts.de |

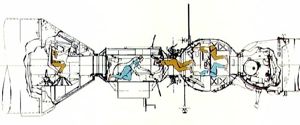

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Artist's concept of Apollo-Soyuz docking in earth's orbit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Artist concept of American Apollo spacecraft docked with Soviet spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Artist's drawing of internal arrangement of orbiting Apollo & Soyuz crafts Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) View of launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome showing Soyuz spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Astronauts and Cosmonauts sightseeing at Red Square in Moscow Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Mock-ups of USSR Soyuz spacecraft on display at Star City Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Close-up view of descent vehicle of Soyuz spacecraft training mock-up Credit: NASA |

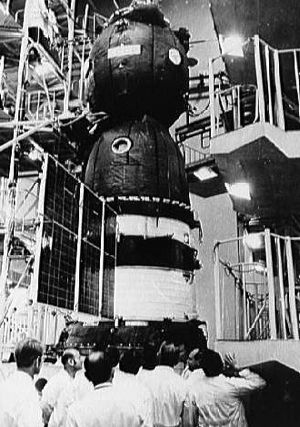

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soviet Soyuz spacecraft seen during prelaunch preparations in U.S.S.R. Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Interior view of descent vehicle of Soyuz spacecraft mock-up Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Two Soviet crewmen for ASTP mission photographed at launch pad Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soyuz space vehicle is launched to begin joint U.S.-USSR ASTP mission Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Launch of the Apollo spacecraft to begin ASTP mission Credit: NASA |

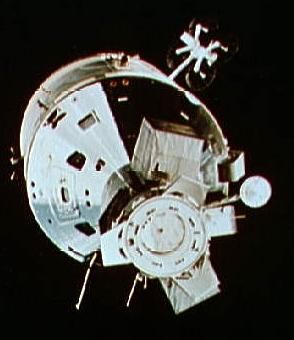

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) American Apollo spacecraft as seen from Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) American Apollo spacecraft as seen from Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) American Apollo spacecraft as seen from Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) American Apollo spacecraft as seen from Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soviet Soyuz spacecraft contrasted against a black-sky background Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soviet Soyuz spacecraft contrasted against a black-sky background Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soviet Soyuz spacecraft contrasted against a black-sky background Credit: NASA |

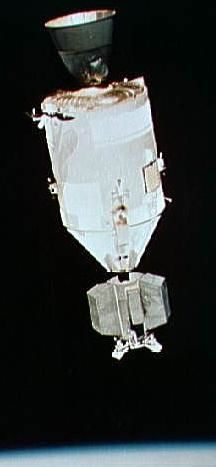

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit as seen from American Apollo spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in orbit as seen from American Apollo spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) View of Los Angeles, California area Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) Sun glint in South Western Pacific Ocean Credit: NASA |

| Apollo 18 (ASTP) ASTP Apollo Command Module nears touchdown in Central Pacific Credit: NASA |

1968 April 12 - .

- Wiring harness problems in Apollo CSM discussed - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Rees. Program: Apollo. Flight: Apollo (ASTP). Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Block II. Apollo Special Task Team Director Eberhard Rees wrote Dale D. Myers at North American Rockwell: "As you are well aware, many manhours have been spent investigating and discussing the radially cracked insulation on wire supplied by Haveg Industries. . Additional Details: here....

1969 November 5 - .

- Space rescue and emergency coordination said to offer opportunities to bring the space-faring nations of the world closer together. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

Space rescue and emergency coordination said to offer opportunities to bring the space-faring nations of the world closer together. Olin E. Teague, Chairman of the House of Representatives Committee on Science and Astronautics Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight, suggested that space rescue and emergency coordination would offer opportunities to bring the space-faring nations of the world closer together. In an initial response to the letter, NASA Hq appointed a Space Station Safety Advisor and established a Shuttle Safety Advisory Panel.

1970 September 4 - .

- Crews from other countries could visit Skylab in orbit. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

An inquiry as to the feasibility of having a crew from another country visit the Skylab in orbit showed that, while there was nothing to indicate such a mission could not be accomplished, a considerable amount of joint planning and design would be required.

1971 March 17 - .

- MSC completed a study for the use of uncommitted flight hardware from the Apollo and Skylab programs. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

The study was limited to low-Earth-orbit manned missions to be down prior to the start of Space Shuttle operations in the late 1970s. Based on various considerations, the study recommended three missions: two Earth resources surveys and the Apollo-Soyuz mission. A further study would be made to determine a specific mission for the fourth available spacecraft.

1971 August 27 - .

- Missions for the immediate post-Skylab period - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

Missions still under consideration for the immediate post-Skylab period included the following: An independent CSM mission for Earth observations. An independent CSM mission for rendezvous and docking with the U.S.S.R. Salyut spacecraft. A combination of the above. Use of the Skylab backup CSM to conduct a cooperative docking with the Salyut vehicle and thereafter carry out a fourth visit to Skylab. This mission would occur approximately 18 months after the launch of Skylab. A second Skylab supported by two 90-day CSMs and a rescue vehicle.

1972 September 28 - .

- CSM 119 would be utilized in a dual role: as a spacecraft rescue vehicle for the Skylab Program and later for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. - . Nation: USA. Program: Skylab. Flight: Apollo (ASTP), Skylab Rescue. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo CSM. Spacecraft: Apollo Rescue CSM. CSM 119 would be utilized in a dual role: as a spacecraft rescue vehicle for the Skylab Program and later for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. However, CSM 111 would continue to be the primary Apollo- Soyuz Test Project spacecraft..

1973 September 13 - .

- Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) revisit to Skylab in mid-1975 feasible. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Skylab.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

Discussions confirmed that there was reasonable assurance that an Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) revisit to Skylab in mid-1975 was feasible. However, such a dual mission would create a significant planning problem for the operations team and would introduce many new considerations to the inflight planning and execution because of uncertainties in the orbital mechanics.

1973 September 15 - .

- Television programs not recommended for ASTP. - . Nation: USA. Program: ASTP. Flight: Apollo (ASTP). The Director of the Skylab Program, in offered his counterpart in the ASTP some advice in establishing an ASTP television program.. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 15 - . 12:20 GMT - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC1. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Soyuz-U.

- Soyuz 19 (ASTP) - .

Call Sign: Soyuz (Union ). Crew: Kubasov,

Leonov.

Backup Crew: Filipchenko,

Rukavishnikov.

Support Crew: Andreyev,

Dzhanibekov,

Ivanchenkov,

Romanenko.

Payload: Soyuz ASTP s/n 75 (EPSA). Mass: 6,790 kg (14,960 lb). Nation: Russia.

Agency: MOM.

Program: ASTP.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Flight: Apollo (ASTP),

Soyuz 19 (ASTP).

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Soyuz 7K-TM.

Duration: 5.94 days. Decay Date: 1975-07-21 . USAF Sat Cat: 8030 . COSPAR: 1975-065A. Apogee: 220 km (130 mi). Perigee: 186 km (115 mi). Inclination: 51.80 deg. Period: 88.50 min.

Soyuz 19 initial orbital parameters were 220.8 by 185.07 kilometres, at the desired inclination of 51.80°, while the period of the first orbit was 88.6 minutes. On 17 July the two spacecraft docked. The crew members rotated between the two spacecraft and conducted various mainly ceremonial activities. Leonov was on the American side for 5 hours, 43 minutes, while Kubasov spent 4:57 in the command and docking modules.

After being docked for nearly 44 hours, Apollo and Soyuz parted for the first time and were station-keeping at a range of 50 meters. The Apollo crew placed its craft between Soyuz and the sun so that the diameter of the service module formed a disk which blocked out the sun. After this experiment Apollo moved towards Soyuz for the second docking.

Three hours later Apollo and Soyuz undocked for the second and final time. The spacecraft moved to a 40 m station-keeping distance so that an ultraviolet absorption experiment could be performed. With all the joint flight activities completed, the ships went on their separate ways.

1975 July 15 - . 19:50 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC39B. Launch Platform: LUT1. LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB.

- Apollo (ASTP) - .

Call Sign: Apollo. Crew: Brand,

Slayton,

Stafford.

Backup Crew: Bean,

Evans,

Lousma.

Payload: Apollo CSM 111. Mass: 14,768 kg (32,557 lb). Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA Houston.

Program: ASTP.

Class: Moon.

Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Flight: Apollo (ASTP),

Soyuz 19 (ASTP).

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM.

Duration: 9.06 days. Decay Date: 1975-07-24 . USAF Sat Cat: 8032 . COSPAR: 1975-066A. Apogee: 166 km (103 mi). Perigee: 152 km (94 mi). Inclination: 51.70 deg. Period: 87.60 min.

This flight marked the culmination of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, a post-moon race 'goodwill' flight to test a common docking system for space rescue. 15 July 1975 began with the flawless launch of Soyuz 19. Apollo followed right on schedule. Despite a stowaway - a 'super Florida mosquito' - the crew accomplished a series of rendezvous manoeuvres over the next day resulting in rendezvous with Soyuz 19. At 11:10 on 17 July the two spacecraft docked. The crew members rotated between the two spacecraft and conducted various mainly ceremonial activities. Stafford spent 7 hours, 10 minutes aboard Soyuz, Brand 6:30, and Slayton 1:35. Leonov was on the American side for 5 hours, 43 minutes, while Kubasov spent 4:57 in the command and docking modules.

After being docked for nearly 44 hours, Apollo and Soyuz parted for the first time and were station-keeping at a range of 50 meters. The Apollo crew placed its craft between Soyuz and the sun so that the diameter of the service module formed a disk which blocked out the sun. This artificial solar eclipse, as viewed from Soyuz, permitted photography of the solar corona. After this experiment Apollo moved towards Soyuz for the second docking.

Three hours later Apollo and Soyuz undocked for the second and final time. The spacecraft moved to a 40 m station-keeping distance so that the ultraviolet absorption (UVA MA-059) experiment could be performed. This was an effort to more precisely determine the quantities of atomic oxygen and atomic nitrogen existing at such altitudes. Apollo, flying out of plane around Soyuz, projected monochromatic laser-like beams of light to retro-reflectors mounted on Soyuz. On the 150-meter phase of the experiment, light from a Soyuz port led to a misalignment of the spectrometer, but on the 500-meter pass excellent data were received; on the 1,000-meter pass satisfactory results were also obtained.

With all the joint flight activities completed, the ships went on their separate ways. On 20 July the Apollo crew conducted earth observation, experiments in the multipurpose furnace (MA-010), extreme ultraviolet surveying (MA-083), crystal growth (MA-085), and helium glow (MA-088). On 21 July Soyuz 19 landed safely in Kazakhstan. Apollo continued in orbit on 22-23 July to conduct 23 independent experiments - including a doppler tracking experiment (MA-089) and geodynamics experiment (MA-128) designed to verify which of two techniques would be best suited for studying plate tectonics from earth orbit.

After donning their space suits, the crew vented the command module tunnel and jettisoned the docking module. The docking module would continue on its way until it re-entered the earth's atmosphere and burned up in August 1975.

1975 July 16 - .

- Apollo (ASTP) - Wakeup Song: Good Morning Sunshine - . Flight: Apollo (ASTP). "Good Morning Sunshine" Chicago - (Apollo crew).

1975 July 16 - .

- ASTP - Rendezvous Maneuvers - . Nation: USA. Program: ASTP. Flight: Apollo (ASTP), Soyuz 19 (ASTP). Apollo and Soyuz modify their orbits in preparation for the docking in space planned for the next day.. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 17 - .

- ASTP - The 'Handshake in Space'. - . Nation: USA. Program: ASTP. Flight: Apollo (ASTP), Soyuz 19 (ASTP). Apollo and Soyuz successfully dock and members of the American and Russian crews shake hands in space for the first time. With the Soviet-American détente crumbling, it will be the last such docking for 20 years.. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 18 - .

- ASTP-Crew transfers between the docked vehicles. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: ASTP.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP),

Soyuz 19 (ASTP).

The crew members take turns visiting each other's capsules, a complicated procedure due to the need to keep both spacecraft manned at all times and for the transfer crews to transition in the docking module between the different Soyuz and Apollo cabin atmospheres. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 18 - .

- Apollo (ASTP) - Wakeup Song: Midnight in Moscow - . Flight: Apollo (ASTP). "Midnight in Moscow" - (Apollo crew).

1975 July 19 - .

- Apollo (ASTP) - Wakeup Song: Tenderness - . Flight: Apollo (ASTP). "Tenderness" Maya Kristalinskaya. Crew did not wake until later in morning - (Apollo crew).

1975 July 19 - .

- ASTP - Joint Apollo/Soyuz flight activities - .

Nation: USA.

Program: ASTP.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP),

Soyuz 19 (ASTP).

During day five of the flight, the crews concentrated on docking exercises and experiments that involved the two ships in the undocked mode. During the interval between the first undocking and the second docking, the Apollo crew placed its craft between Soyuz and the sun so that the diameter of the service module formed a disk which blocked out the sun. This artificial solar eclipse, as viewed from Soyuz, permitted Leonov and Kubasov to photograph the solar corona. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 20 - .

- Apollo (ASTP) - Wakeup Song: Tenderness - . Flight: Apollo (ASTP). "Tenderness" Maya Kristalinskaya . This time the crew heard it. (Apollo crew).

1975 July 20 - .

- ASTP - Separate Apollo/Soyuz activities - . Nation: USA. Program: ASTP. Flight: Apollo (ASTP), Soyuz 19 (ASTP). Apollo and Soyuz, now flying in separate orbits, conduct independent experiments prior to their return to earth.. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 21 - .

- ASTP - Soyuz returns to earth, Apollo remains in orbit. - .

Nation: Russia.

Program: ASTP.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP),

Soyuz 19 (ASTP).

Following a rest period of nearly 10 hours, the Soyuz crewmen advised the ground that they were awake and that all systems were normal. The deorbit burn came exactly on time (5:09 in Houston), and the Soyuz crew landed safely in Kazakhstan. For the remaining three and a half days, Stafford, Slayton, and Brand would concentrate on their experiments, but in many respects the saga of Apollo and Soyuz had come to an end.

1975 July 21 - .

- Landing of Soyuz 19 (ASTP) - . Return Crew: Kubasov, Leonov. Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Kubasov, Leonov. Program: ASTP. Flight: Apollo (ASTP), Soyuz 19 (ASTP). Soyuz 19 landed safely at 10:51 GMT, 87 km north-east of Arkalyk, 9. 6 km from its aim point..

1975 July 23 - .

- Apollo (ASTP) in-flight experiments - .

Nation: USA.

Program: ASTP.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

Some minor experiment hardware problems developed during the final days of the mission, but for the most part the crew members worked through their flight plan - which included 23 independent experiments - with few difficulties. After a relatively quiet day of work on the 22nd, the major part of the 23rd was devoted to preparing for and conducting the doppler tracking experiment (MA-089). The day was also marked by a press conference from space and jettison of the docking module. Additional Details: here....

1975 July 24 - .

- Apollo (ASTP) - Wakeup Song: Redneck Mother - . Flight: Apollo (ASTP). "Redneck Mother" Jerry Jeff Walker (Apollo crew).

1975 July 24 - .

- Landing of Apollo (ASTP) - .

Return Crew: Brand,

Slayton,

Stafford.

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Brand,

Slayton,

Stafford.

Program: ASTP.

Flight: Apollo (ASTP).

Apollo (ASTP) landed at 21:18 GMT, 7.3 km from the recovery ship New Orleans. It was the last splashdown of an American space capsule. However the flight of the last Apollo spacecraft was marred by the fact that the crew almost perished while the capsule was descending under its parachute.

A failure in switchology led the automatic landing sequence to be not armed at the same time the reaction control system was still active. When the Apollo hadn't begun the parachute deployment sequence by 7,000 metres altitude, Brand hit the manual switches for the apex cover and the drogues. The manual deployment of the drogue chutes caused the CM to sway, and the reaction control system thrusters worked vigorously to counteract that motion. When the crew finally armed the automatic ELS 30 seconds later, the thruster action terminated.

During that 30 seconds, the cabin was flooded with a mixture of toxic unignited propellants from the thrusters. Prior to drogue deployment, the cabin pressure relief valve had opened automatically, and in addition to drawing in fresh air it also brought in unwanted gases being expelled from the roll thrusters located about 0.6 meter from the relief valve. Brand manually deployed the main parachutes at about 2,700 meters despite the gas fumes in the cabin.

By the time of splashdown, the crew was nearly unconscious from the fumes, Stafford managed to get an oxygen mask over Brand's face. He then began to come around. When the command module was upright in the water, Stafford opened the vent valve, and with the in-rush of air the remaining fumes disappeared. The crew ended up with a two-week hospital stay in Honolulu. For Slayton, it also meant the discovery of a small lesion on his left lung and an exploratory operation that indicated it was a non-malignant tumour. Additional Details: here....

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use