Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Gemini

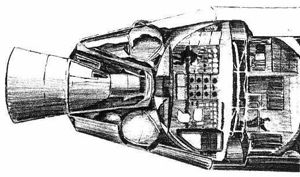

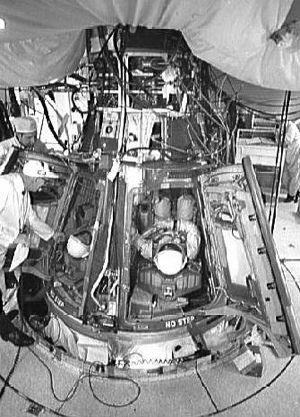

Gemini preflight

Gemini spacecraft being prepared in the shop.

Credit: NASA

Status: Operational 1964. First Launch: 1964-04-08. Last Launch: 1966-11-11. Number: 13 . Thrust: 706 N (158 lbf). Gross mass: 3,851 kg (8,490 lb). Unfuelled mass: 3,396 kg (7,486 lb). Specific impulse: 273 s. Height: 5.67 m (18.60 ft).

It was obvious to NASA that there was a big gap of three to four years between the last Mercury flight and the first scheduled Apollo flight. There would therefore be no experience in the US in understanding the problems of orbital maneuvering, rendezvous, docking, lifting re-entry, and space walking before the Apollo flights, which required all of these to be successfully accomplished to complete the lunar landing mission.

Gemini began as Mercury Mark II to fill this gap. The concept was to enlarge the Mercury capsule's basic design to accommodate two crew, provide it with orbital maneuvering capability, use existing boosters to launch it and an existing upper rocket stage as a docking target. The latest aircraft engineering was exploited , resulting in a modularized design that provided easy access to and changeout of equipment mounted external to the crew's pressure vessel. In many ways the Gemini design was ahead of that of the Apollo, since the project began two years later . The crew station layout was similar to that of the latest military fighters; the capsule was equipped with ejection seats, inertial navigation, the pilot's traditional 8-ball attitude display, and radar. The escape tower used for Mercury was deleted; the propellants used in the Titan II launch vehicle, while toxic, corrosive, poisonous, and self-igniting, did not explode in the manner of the Atlas or Saturn LOX/Kerosene combination. The ejection seats served as the crew escape method in the lower atmosphere, just as in a high-performance aircraft. The seats were also needed for the original landing mode, which involved deployment of a huge inflated Rogallo wing (ancestor of today's hang gliders) with a piloted landing on skids at Edwards Dry Lake. In the event, the wing could not be made to deploy reliably before flights began, so the capsule made a parachute-borne water landing, much to the astronauts' chagrin.

All around the Gemini was considered the ultimate 'pilot's spacecraft', and it was also popular with engineers because of its extremely light weight. The capsule allowed recover of a crew of two for only 50% more than the Mercury capsule weight, and half of the weight per crew member of the Apollo design. The penalty was obvious - it was christened the 'Gusmobile' since diminutive Gus Grissom was the only astronaut who was said to be able to fit into it. The crew member was crammed in, shoulder to shoulder with his partner, his helmet literally scrunched against the hatch, which could be opened for space walks. With the crew unable to fully stretch out unless an EVA was scheduled, living in the capsule was literally painful on the long missions (Gemini 5 and 7). Getting back into the seat and getting the hatch closed in an inflated suit in zero gravity was problematic and would have been impossible if the spacewalking astronaut was incapacitated in even a minor way.

Early on it was proposed that the Gemini could be used for manned circumlunar or lunar missions at a fraction of the cost and much earlier than Apollo. Truth be told, a Gemini launched atop a Titan 3E or Saturn IVB Centaur could have accomplished a circumlunar flight as early as 1966 and, using earth orbit rendezvous techniques, a landing at least a year before Apollo. But the capsule, while perhaps suited as a ferry vehicle to space stations, would have been quite marginal for the lunar mission due to the cramped accommodation. But mainly NASA was fully committed to the Apollo program, which was grounded on a minimum three man crew and minimum 10,000 pound command module weight.

At a cost of 5% of the Apollo project, NASA staged twelve flights, ten of them manned, in the course of which the problems of rendezvous, docking, and learning how to do work in a spacesuit in zero-G were tackled and solved. It is said that not much of this was fed back to Apollo, since the two projects had completely different sets of contractors and there was little cross-fertilization in the rendezvous and docking areas. But it is undeniable that important issues in regard to working in zero-G were discovered and solved and both flight and ground crews gained experience that would make the Apollo flights successful.

Gemini was to have continued to fly into the 1970's as the return capsule of the USAF Manned Orbiting Laboratory program. However with the MOL's cancellation in 1969 work at McDonnell came to an end and the last models of the finest spacecraft ever built were scrapped.

Unit Cost $: 13.000 million. Crew Size: 2. Habitable Volume: 2.55 m3. RCS total impulse: 1,168 kgf-sec. Spacecraft delta v: 98 m/s (321 ft/sec). Electric System: 151.00 kWh. Electric System: 2.16 average kW.

More at: Gemini.

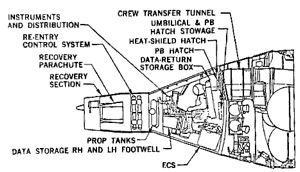

| Gemini AM American manned spacecraft module. 12 launches, 1964.04.08 (Gemini 1) to 1966.11.11 (Gemini 12). |

| Gemini EM American manned spacecraft module. 12 launches, 1964.04.08 (Gemini 1) to 1966.11.11 (Gemini 12). |

| Gemini: Lunar Gemini The Gusmobile might have gotten on the moon faster, quicker, cheaper (but not better...) |

| Gemini RM American manned spacecraft module. 12 launches, 1964.04.08 (Gemini 1) to 1966.11.11 (Gemini 12). |

| Gemini LOR American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. Original Mercury Mark II proposal foresaw a Gemini capsule and a single-crew open cockpit lunar lander undertaking a lunar orbit rendezvous mission, launched by a Titan C-3. |

| Gemini Lunar Lander American manned lunar lander. Study 1961. A direct lunar lander design of 1961, capable of being launched to the moon in a single Saturn V launch through use of a 2-man Gemini re-entry vehicle instead of the 3-man Apollo capsule. |

| Gemini-Centaur American manned lunar flyby spacecraft. Study 1962. In the first Gemini project plans, it was planned that after a series of test dockings between Gemini and Agena rocket stages, Geminis would dock with Centaur stages for circumlunar flights. |

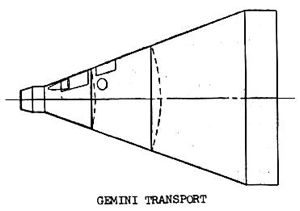

| Gemini Transport American logistics spacecraft. Study 1963. This Gemini Transport version was proposed as a Gemini program follow-on in 1963. With the extended reentry module, this was the ancestor of the Big Gemini spacecraft of the late 1960's. |

| Gemini Ferry American manned spacecraft. Study 1963. The Gemini Ferry vehicle would have been launched by Titan 3M for space station replenishment. |

| Gemini Ferry AM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1963. |

| Gemini Ferry CM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1963. |

| Gemini Ferry RM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1963. |

| Gemini 1 Manned spacecraft prototype satellite built by McDonnell-Douglas for NASA, USA. Launched 1964. |

| Gemini Pecan American manned space station. Study 1964. |

| Gemini - Saturn I American manned lunar flyby spacecraft. Study 1964. In the spring of 1964, with manned Apollo flights using the Saturn I having been cancelled, use of a Saturn I to launch a Gemini around the moon was studied. |

| Gemini - Saturn IB American manned lunar flyby spacecraft. Study 1964. |

| Gemini - Saturn V American manned lunar orbiter. In late 1964 McDonnell, in addition to a Saturn 1B-boosted circumlunar Gemini, McDonnell proposed a lunar-orbit version of Gemini to comprehensively scout the Apollo landing zones prior to the first Apollo missions. |

| Gemini 3 First spacecraft to maneuver in orbit. First manned flight of Gemini spacecraft. First American to fly twice into space. Manual reentry, splashed down 97 km from carrier. |

| Gemini 4 First American space walk. First American long-duration spaceflight. Astronaut could barely get back into capsule after spacewalk. Failure of spacecraft computer resulted in high-G ballistic re-entry. |

| Gemini - Double Transtage American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1965. In June 1965 astronaut Pete Conrad conspired with the Martin and McDonnell corporations to advocate an early circumlunar flight using Gemini. |

| Gemini 5 First American flight to seize duration record from Soviet Union. Mission plan curtailed due to fuel cell problems; mission incredibly boring, spacecraft just drifting to conserve fuel most of the time. Splashed down 145 km from aim point. |

| GATV 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Docking Target satellite for NASA, USA. Launched 1965 - 1966. |

| Gemini 7 Record flight duration (14 days) to that date. Incredibly boring mission, made more uncomfortable by the extensive biosensors. Monotony was broken just near the end by the rendezvous with Gemini 6. |

| Gemini 6 First rendezvous of two spacecraft. Originally was to dock with an Agena target, but this blew up on way to orbit. Decision to rendezvous with upcoming Gemini 7 instead. Mission almost lost when booster ignited, then shut down on pad. |

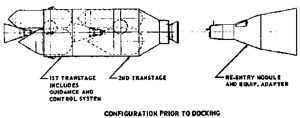

| Extended Mission Gemini American manned spacecraft. Study 1965. A McDonnell concept for using Gemini for extended duration missions. The basic Gemini would dock with an Agena upper stage. |

| Gemini Satellite Inspector American manned spacecraft. Study 1965. A modification of Gemini to demonstrate rendezvous and inspection of noncooperative satellites was proposed. The Gemini would rendezvous with the enormous Pegasus satellite in its 500 x 700 km orbit. |

| Gemini 8 First docking of two spacecraft. After docking with Agena target, a stuck thruster aboard Gemini resulted in the crew nearly blacking out before the resulting spin could be stopped. An emergency landing in the mid-Pacific Ocean followed. |

| Gemini Lunar Surface Rescue Spacecraft American manned lunar lander. Study 1966. This version of Gemini would allow a direct manned lunar landing mission to be undertaken in a single Saturn V flight, although it was only proposed as an Apollo rescue vehicle. |

| Gemini LSRS AM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1966. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft, dimensions of propellant tanks. |

| Gemini LSRS LM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1966. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft, dimensions of propellant tanks. |

| Gemini LSRS LOIM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1966. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft, dimensions of propellant tanks. |

| Gemini LSRS RM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1966. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft. |

| Gemini 9A Planned mission, cancelled when prime crew killed in T-38 trainer crash. All subsequent crew assignments were reshuffled. This ended up determining who would be the first man on the moon.… |

| Gemini 9 Third rendezvous mission of Gemini program. Agena target blew up on way to orbit; substitute target's shroud hung up, docking impossible. EVA almost ended in disaster when astronaut's face plate fogged over; barely able to return to spacecraft. |

| Gemini 10 First free space walk from one spacecraft to another. First rendezvous with two different spacecraft in one flight. Altitude (763 km) record. Exciting mission with successful docking with Agena, flight up to parking orbit where Gemini 8 Agena was stored. |

| Gemini 11 First docking with another spacecraft on first orbit after launch. First test of tethered spacecraft. Speed (8,003 m/s) and altitude (1,372 km) records. |

| Gemini-B Experimental manned spacecraft built by McDonnell-Douglas for USAF, USA. Launched 1966. |

| Gemini 12 First completely successful space walk. Final Gemini flight. Docked and redocked with Agena, demonstrating various Apollo scenarios including manual rendezvous and docking. Successful EVA without overloading suit by use of suitable restraints. |

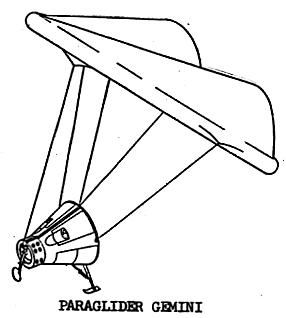

| Gemini Paraglider American manned spacecraft. The paraglider was supposed to be used in the original Gemini program but delays in getting the wing to deploy reliably resulted in it not being flown. |

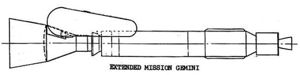

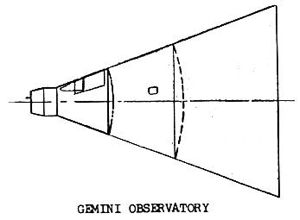

| Gemini Observatory American manned spacecraft. Study 1966. Proposed version of Gemini for low-earth orbit solar or stellar astronomy. This would be launched by a Saturn S-IB. It has an enlarged reentry module which seems to be an ancestor of the 'Big Gemini' of 1967. |

| Rescue Gemini American manned rescue spacecraft. Study 1966. A version of Gemini was proposed for rescue of crews stranded in Earth orbit. This version, launched by a Titan 3C, used a transtage for maneuvering. |

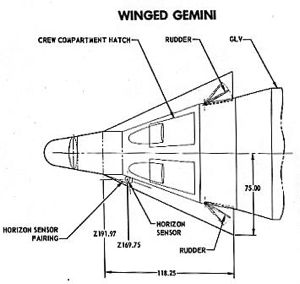

| Winged Gemini American manned spaceplane. Study 1966. Winged Gemini was the most radical modification of the basic Gemini reentry module ever considered. |

| Gemini Lunar RM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1967. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft. |

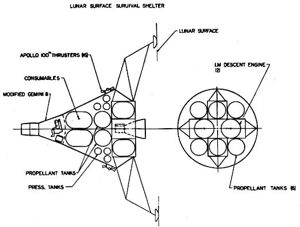

| Gemini Lunar Surface Survival Shelter American manned lunar habitat. Study 1967. Prior to an Apollo moon landing attempt, the shelter would be landed, unmanned, near the landing site of a stranded Apollo Lunar Module. |

| Gemini LSSS LM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1967. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft, dimensions of propellant tanks. |

| Gemini LSSS SM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1967. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft. |

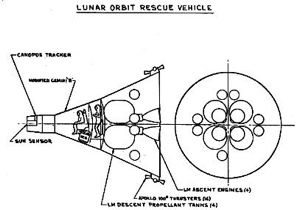

| Gemini LORV American manned lunar orbiter. Study 1967. This version of Gemini was studied as a means of rescuing an Apollo CSM crew stranded in lunar orbit. The Gemini would be launched unmanned on a translunar trajectory by a Saturn V. |

| Gemini LORV RM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1967. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft. |

| Gemini LORV SM American manned spacecraft module. Study 1967. Calculated mass based on mission requirements, drawing of spacecraft, dimensions of propellant tanks. |

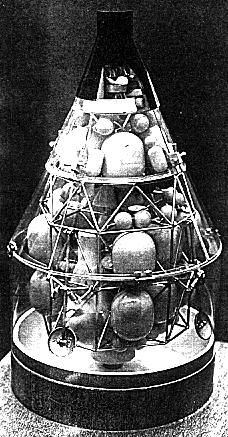

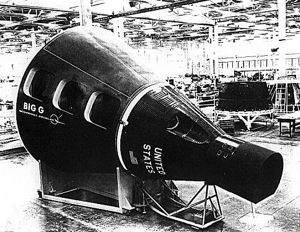

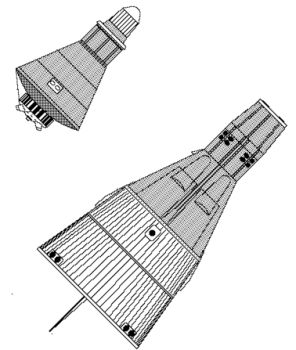

| Big Gemini American manned spacecraft. Reached mockup stage 1967. |

| Big Gemini AM American manned spacecraft module. Reached mockup stage 1967. Earth orbit maneuver and retrofire. |

| Big Gemini CM American manned spacecraft module. Reached mockup stage 1967. Space station resupply. |

| Big Gemini RV American manned spacecraft module. Reached mockup stage 1967. Crew and cargo return. |

| Gemini B American manned spacecraft. Cancelled 1969. Gemini was extensively redesigned for the MOL Manned Orbiting Laboratory program. The resulting Gemini B, although externally similar, was essentially a completely new spacecraft. |

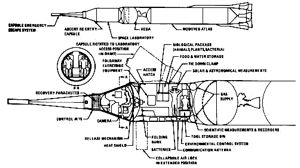

| Gemini Technical Description Gemini System Details |

| By Gemini to Mars! In the 1960's many considered use of the cramped two-man Gemini reentry vehicle for journeys to the moon problematic. But there was even a proposal for use of Gemini on a mission to Mars… |

Family: Manned spacecraft. People: McDonnell, Schirra, Grissom, Cooper, See, Borman, Lovell, McDivitt, Gordon, Aldrin, Conrad, Armstrong, Stafford, Young, Collins, White, Bean, Scott, Williams, Clifton, Anders, Cernan. Country: USA. Engines: Star 13E. Spacecraft: Gemini AM, Gemini EM, Gemini RM, Gemini Agena Target Vehicle, Atlas Target Docking Adapter. Flights: Gemini 3, Gemini 4, Gemini 5, Gemini 7, Gemini 6, Gemini 8, Gemini 9A, Gemini 9, Gemini 10, Gemini 11, Gemini 12. Launch Vehicles: Titan II GLV. Propellants: N2O4/MMH. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral, Cape Canaveral LC19, Cape Canaveral LC40. Agency: NASA, NASA Houston. Bibliography: 137, 16, 18, 183, 2, 2066, 2147, 2148, 2149, 2151, 2152, 2153, 2155, 2156, 2157, 2158, 2161, 2166, 2167, 2168, 2169, 2170, 2171, 22, 2204, 2205, 26, 27, 279, 33, 344, 40, 44, 483, 6, 60, 66, 4951, 12482, 12483.

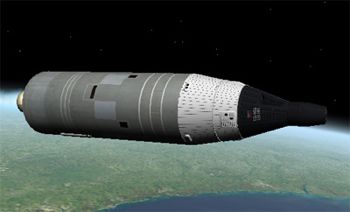

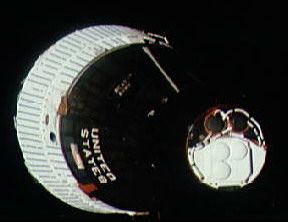

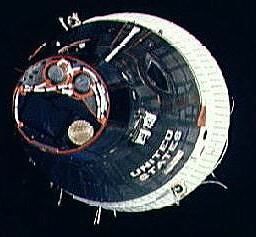

| Gemini6 in orbit Gemini6 in orbit view e Credit: NASA |

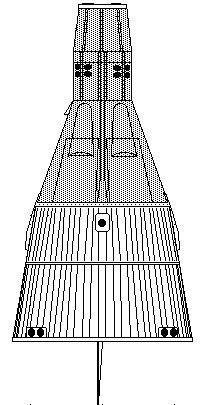

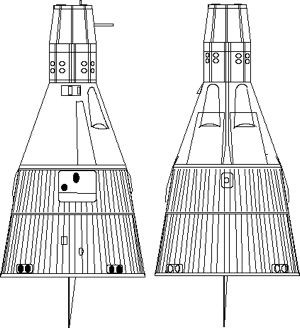

| Gemini Spacecraft Credit: © Mark Wade |

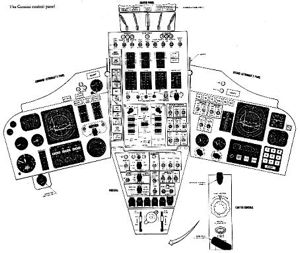

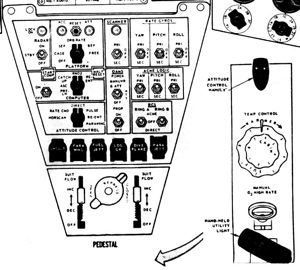

| Gemini Control Panel Control panel of the basic Gemini (454 x 383 pixel image). Credit: NASA |

| Gemini Control Panel Control panel of the basic Gemini (903 x 765 pixel image). Credit: NASA |

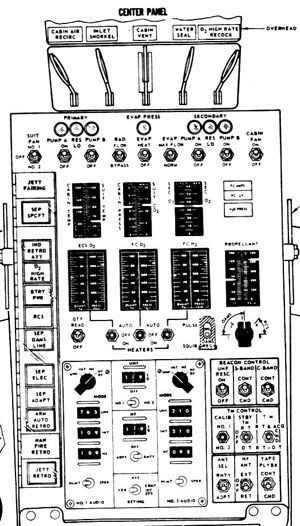

| Gemini Control Panel Gemini Control Panel - close-up of the second astronaut (right hand side) controls. Credit: NASA |

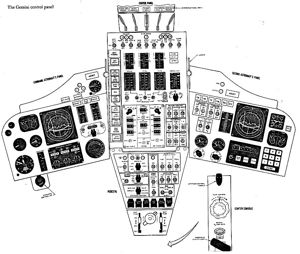

| Gemini Control Panel Gemini Control Panel - close-up of the centre panel and overhead controls. Credit: NASA |

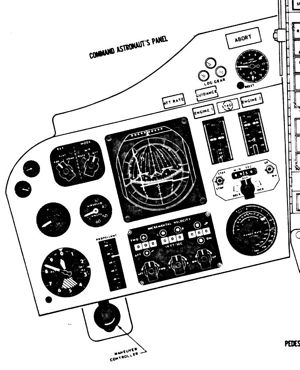

| Gemini Control Panel Gemini Control Panel - close-up of the command astronaut (left hand seat) controls. Credit: NASA |

| Titan 2 Gemini The Titan 2 ICBM was used for launch of the Gemini manned spacecraft. Credit: NASA |

| Gemini Control Panel Gemini control panel - close-up of the pedestal controls between the two astronauts. Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 1 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Gemini 4 Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| MOL Mockup Credit: Manufacturer Image |

| Gemini Paraglider Credit: McDonnell Douglas |

| Mercury II Station Credit: NASA |

| Early Gemini Concept Credit: NASA |

| Gemini Credit: © Mark Wade |

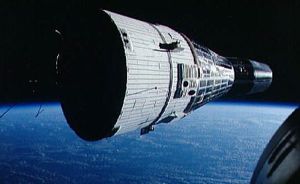

| Gemini6 in orbit Gemini6 in orbit view g Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 6 in orbit Gemini 6 in orbit view d Credit: NASA |

| Gemini6 in orbit Gemini6 in orbit view f Credit: NASA |

| Gemini6 in orbit Gemini6 in orbit view j Credit: NASA |

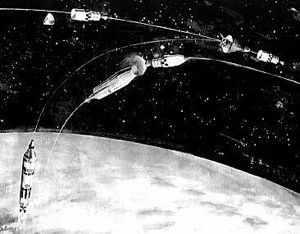

| Gemini 6 2 View of Gemini 6 during the Gemini 6 and 7 first space rendezvous. Credit: NASA |

| MOL Credit: © Dan Roam |

| Gemini 6 3 View of Gemini 6 during the Gemini 6 and 7 first space rendezvous. Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 6 View of Gemini 6 during the Gemini 6 and 7 first space rendezvous. Credit: NASA |

| Gemini6 in orbit Gemini6 in orbit view Credit: NASA |

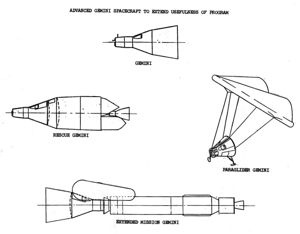

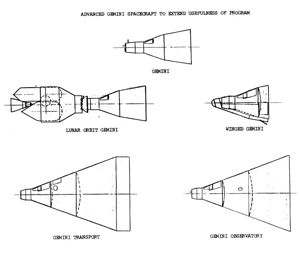

| Gemini Variants Modest modifications of Gemini proposed by McDonnell Douglas as a follow-on to the basic program (927 x 723 pixel version). Credit: McDonnell Douglas |

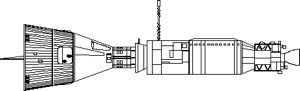

| Gemini-Agena Gemini docked to Agena Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Gemini Advanced More advanced versions of Gemini proposed by McDonnell Douglas as a follow-on to the basic program (927 x 723 pixel version). Credit: McDonnell Douglas |

| Gemini-Centaur Gemini Docked to Centaur for Circumlunar Flight Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Gemini-Centaur-LM Gemini for lunar landing with Centaur and Langley open cockpit Lunar Module Credit: © Mark Wade |

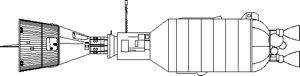

| Gemini/Transtage-LEO Translunar Gemini with Double Transtage - LEO Configuration Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Extended Gemini Credit: McDonnell Douglas |

| Gemini Ferry Drawing of Gemini Ferry in flight. Credit: McDonnell-Douglas |

| Gemini Observatory Credit: McDonnell Douglas |

| Mercury Gemini Comparison of the Mercury and Gemini capsules. Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Atlas ATDA Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Gemini 2 view Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Gemini 5 Astronauts Cooper and Conrad in Gemini spacecraft just after insertion Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 5 Astronaut Charles Conrad inside the Gemini 5 spacecraft after launch Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 8 Astronauts Scott and Armstrong inserted into Gemini 8 spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 8 Gemini 8 spacecraft hoisted aboard the U.S.S. Leonard F. Mason Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 9 View of the nose of the Gemini 9 spacecraft taken from hatch of spacecraft Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 9 Close-up view of Gemini 9 spacecraft taken during EVA Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 9 Gemini 9-A spacecraft touches down in the Atlantic at end of mission Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 9 Gemini 9 spacecraft recovery operations Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 9 Gemini 9 astronauts await recovery operations Credit: NASA |

| Gemini 9 Gemini 9-A spacecraft touches down in the Atlantic at end of mission Credit: NASA |

During 1958 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas Vega.

- NASA sketches two-crew Mercury follow-on spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Caldwell.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

In 1958 H. Kurt Strass and Caldwell C. Johnson of NASA's Space Task Group at Langley Field, Virginia.sketched a spacecraft design concept for a two-man orbiting laboratory to be launched by an Atlas-Vega booster. This was one of the earliest sketches of a two-crew Mercury follow-on. The Vega stage was dropped in favour of the Agena a year later, and a similar one-crew Mercury-Agena space station was proposed by McDonnell some years later.

1959 April 1 - .

- Two-man Mercury capsule proposed. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Goett.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

H. Kurt Strass of the Space Task Group (STG) at Langley Field, Virginia described some preliminary ideas of STG planners regarding a follow-on to Mercury: (1) an enlarged Mercury capsule to place two men in orbit for three days; (2) a two-man Mercury capsule and a large cylindrical structure to support a two-week mission. (In its 1960 budget, NASA had requested $2 million to study methods of constructing a manned orbiting laboratory or converting the Mercury spacecraft into a two-man laboratory for extended space missions.) Additional Details: here....

1959 April 24 - .

- NASA budgets for research on techniques and problems of space rendezvous. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

DeMarquis D. Wyatt, Assistant to the Director of Space Flight Development, testified before Congress in support of NASA's request for $3 million in Fiscal Year 1960 for research on techniques and problems of space rendezvous. Wyatt explained that logistic support for a manned space laboratory, a possible post-Mercury flight program, depended upon resolving several key problems and making rendezvous in orbit practical. Among key problems he cited were establishment of methods for fixing the relative positions of two objects in space; development of accurate target acquisition devices to enable supply craft to locate the space station; development of guidance systems to permit precise determination of flight paths; and development of reliable propulsion systems for maneuvering in orbit.

1959 June 22 - .

- Preliminary design of a two-man space laboratory. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

MOL.

H. Kurt Strass of Space Task Group's Flight Systems Division (FSD) recommended the establishment of a committee to consider the preliminary design of a two-man space laboratory. Representatives from each of the specialist groups within FSD would work with a special projects group, the work to culminate in a set of design specifications for the two-man Mercury.

1960 April 5 - .

- Modification of Mercury spacecraft for a controlled reentry begun. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Mercury Mark I.

The Space Task Group notified the Ames Research Center that preliminary planning for the modification of the Mercury spacecraft to accomplish controlled reentry had begun, and Ames was invited to participate in the study. Preliminary specifications for the modified spacecraft were to be ready by the end of the month. This program was later termed Mercury Mark II and eventually Project Gemini.

1960 May 16-17 - .

- NASA conference on space rendezvous. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Representatives of NASA's research centers gathered at Langley Research Center to present papers on current programs related to space rendezvous and to discuss possible future work on rendezvous. During the first day of the conference, papers were read on the work in progress at Langley, Ames, Lewis, and Flight Research Centers, Marshall Space Flight Center, and Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The second day was given to a roundtable discussion. All felt strongly that rendezvous would soon be essential, that the technique should be developed immediately, and that NASA should make rendezvous experiments to develop the technique and establish the feasibility of rendezvous.

1960 June - .

- Space Task Group (STG) issued a set of guidelines for advanced manned space flight programs. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Mercury Mark I.

The document comprised five papers presented by STG personnel at a series of meetings with personnel from NASA Headquarters and various NASA field installations during April and May. Primary focus was a manned circumlunar mission, or lunar reconnaissance, but in his summary, Charles J. Donlan, Associate Director (Development), described an intermediate program that might fit into the period between the phasing out of Mercury and the beginning of flight tests of the multimanned vehicle. During this time, 'it is attractive to consider the possibility of a flight-test program involving the reentry unit of the multimanned vehicle which at times we have thought of as a lifting Mercury.' What form such a vehicle might take was uncertain, but it would clearly be a major undertaking; much more information was needed before a decision could be made. To investigate some of the problems of a reentry vehicle with a lift-over-drag ratio other than zero, STG had proposed wind tunnel studies of static and dynamic stability, pressure, and heat transfer at Langley, Arnold Engineering Development Center, and Ames facilities.

1961 January 5-6 - .

- NASA's Space Exploration Program Council discusses manned lunar landing. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

NASA's Space Exploration Program Council met in Washington to discuss manned lunar landing. Among the results of the meeting was an agreement that NASA should plan an earth-orbital rendezvous program independent of, although contributing to, the manned lunar program.

1961 January 20 - .

- Space Task Group management discusses a follow-on Mercury program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Space Task Group management held a Capsule Review Board meeting. The first topic on the agenda was a follow-on Mercury program. Several types of missions were considered, including long-duration, rendezvous, artificial gravity, and flight tests of advanced equipment. Major conclusion was that a follow-on program needed to be specified in greater detail.

1961 February 13 - .

- NASA and McDonnell began discussions of an advanced Mercury spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Faget,

Gilruth.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

McDonnell had been studying the concept of a maneuverable Mercury spacecraft since 1959. On February 1, Space Task Group (STG) Director Robert R. Gilruth assigned James A. Chamberlin, Chief, STG Engineering Division, who had been working with McDonnell on Mercury for more than a year, to institute studies with McDonnell on improving Mercury for future manned space flight programs. Additional Details: here....

1961 May 5 - .

- Applied orbital operations program - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Integrated research, development, and applied orbital operations program to cost $1 billion through 1970. A NASA Headquarters working group, headed by Bernard Maggin, completed a staff paper presenting arguments for establishing an integrated research, development, and applied orbital operations program at an approximate cost of $1 billion through 1970. The group identified three broad categories of orbital operations: inspection, ferry, and orbital launch. It concluded that future space programs would require an orbital operations capability and that the development of an integrated program, coordinated with Department of Defense, should begin immediately. The group recommended that such a program, because of its scope and cost, be independent of other space programs and that a project office be established to initiate and implement the program.

1961 May 7 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Titan II proposed for lunar landing program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth,

Seamans,

Silverstein.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft Bus: Gemini.

Spacecraft: Gemini LOR.

Albert C. Hall of The Martin Company proposed to Robert C. Seamans, Jr., NASA's Associate Administrator, that the Titan II be considered as a launch vehicle in the lunar landing program. Although skeptical, Seamans arranged for a more formal presentation the next day. Abe Silverstein, NASA's Director of Space Flight Programs, was sufficiently impressed to ask Director Robert R. Gilruth and STG to study the possible uses of Titan II. Silverstein shortly informed Seamans of the possibility of using the Titan II to launch a scaled-up Mercury spacecraft.

1961 May 8 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Martin briefed NASA on the Titan II weapon system. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth,

Seamans.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Mercury Mark I.

Martin Company personnel briefed NASA officials in Washington, D.C., on the Titan II weapon system. Albert C. Hall of Martin had contacted NASA's Associate Administrator, Robert C. Seamans, Jr., on April 7 to propose the Titan II as a launch vehicle for a lunar landing program. Although skeptical, Seamans nevertheless arranged for a more formal presentation. Abe Silverstein, NASA Director, Office of Space Flight Programs, was sufficiently impressed by the Martin briefing to ask Director Robert R. Gilruth and Space Task Group to study possible Titan II uses. Silverstein shortly informed Seamans of the possibility of using the Titan II to launch a scaled-up Mercury spacecraft.

1961 May 17 - .

- Design Study of a Manned Spacecraft Paraglide Landing System. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

Space Task Group (STG) issued a Statement of Work for a Design Study of a Manned Spacecraft Paraglide Landing System. The purpose of the study was to define and evaluate problem areas and to establish the design parameters of a system to provide spacecraft maneuverability and controlled energy descent and landing by aerodynamic lift. McDonnell was already at work on a modified Mercury spacecraft; the proposed paraglide study was to be carried on concurrently to allow the paraglide landing system to be incorporated as an integral subsystem. STG Director Robert R. Gilruth requested that contracts for the design study be negotiated with three companies which already had experience with the paraglide concept: Goodyear Aircraft Corporation, Akron, Ohio; North American Aviation, Inc., Space and Information Systems Division, Downey, California; and Ryan Aeronautical Company, San Diego, California. Each contract would be funded to a maximum of $100,000 for a study to be completed within two and one-half months from the date the contract was awarded. Gilruth expected one of these companies subsequently to be selected to develop and manufacture a paraglide system based on the approved design concept. In less than three weeks, contracts had been awarded to all three companies. Before the end of June, the design study formally became Phase I of the Paraglider Development Program.

1961 June 9 - .

- Chamberlin briefed NASA Headquarters on McDonnell's advanced capsule design. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Low, George.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

James A. Chamberlin, Chief, Engineering Division, Space Task Group (STG), briefed Director Robert R. Gilruth, senior STG staff members, and George M. Low and John H. Disher of NASA Headquarters on McDonnell's advanced capsule design. The design was based on increased component and systems accessibility, reduced manufacturing and checkout time, easier pilot insertion and emergency egress procedures, greater reliability, and adaptability to a paraglide landing system. It departed significantly from Mercury capsule design in placing most components outside the pressure vessel and increasing retrograde and posigrade rocket performance. The group was reluctant to adopt what seemed to be a complete redesign of the Mercury spacecraft, but it decided to meet again on June 12 to review the most desirable features of the new design. After discussing most of these items at the second meeting, the group decided to ask McDonnell to study a minimum-modification capsule to provide an 18-orbit capability.

1961 July 7 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas Centaur LV-3C.

- McDonnell studies of the redesigned Mercury spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Ejection,

Gemini Parachute.

Walter F. Burke of McDonnell summarized the company's studies of the redesigned Mercury spacecraft for Space Task Group's senior staff. McDonnell had considered three configurations: (1) the minimum-change capsule, modified only to improve accessibility and handling, with an adapter added to carry such items as extra batteries; (2) a reconfigured capsule with an ejection seat installed and most of the equipment exterior to the pressure vessel on highly accessible pallets; and (3) a two-man capsule, similar to the reconfigured capsule except for the modification required for two rather than one-man operation. The capsule would be brought down on two Mercury-type main parachutes, the ejection seat serving as a redundant system. In evaluating the trajectory of the two-man capsule, McDonnell used Atlas Centaur booster performance data.

1961 July 27-28 - .

- Representatives of NASA and McDonnell met to decide what course McDonnell's work on the advanced Mercury should take. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Mercury Mark I.

Representatives of NASA and McDonnell met to decide what course McDonnell's work on the advanced Mercury should take. The result: McDonnell was to concentrate all its efforts on two versions of the advanced spacecraft. The first required minimum changes; it was to be capable of sustaining one man in space for 18 orbits. The second, a two-man version capable of advanced missions, would require more radical modifications.

1961 July 27-28 - .

- Advanced Mercury concepts - .

Nation: USA.

Flight: Mercury MA-10,

Mercury MA-11,

Mercury MA-12.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Mercury Mark I.

After the 2-man space concept (later designated Project Gemini) was introduced in May 1961, a briefing between McDonnell and NASA personnel was held on the matter. As a result of this meeting, space flight design effort was concentrated on the 18-orbit 1-man Mercury and on a 2-man spacecraft capable of advanced missions.

1961 August 1 - .

- McDonnell proposal for Gemini - . Nation: USA. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Gemini. Baseline 10 earth orbit flights; also proposed for docking with Centaur and circumlunar flights by March 1965. NASA not interested - threat to Apollo..

1961 August 14 - .

- Report on Mercury Mark II. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Fred J. Sanders and three other McDonnell engineers arrived at Langley Research Center to help James A. Chamberlin and other Space Task Group (STG) engineers who had prepared a report on the improved Mercury concept, now known as Mercury Mark II. Then, with the assistance of Warren J. North of NASA Headquarters Office of Space Flight Programs, the STG group prepared a preliminary Project Development Plan to be submitted to NASA Headquarters. Although revised six times before the final version was submitted on October 27, the basic concepts of the first plan remained unchanged in formulating the program.

1961 August 31 - . LV Family: Saturn V. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-3.

- Chamberlain proposes lunar landing by Gemini - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Gemini. Landing by Gemini using 4,000 kg wet/680 kg empty lander and Saturn C-3 booster. Landing by January 1966..

1961 August - .

- Presentation to STG on rendezvous and the lunar orbit rendezvous plan - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin.

Spacecraft Bus: Gemini.

Spacecraft: Gemini LOR.

John C. Houbolt of Langley Research Center made a presentation to STG on rendezvous and the lunar orbit rendezvous plan. At this time James A. Chamberlin of STG requested copies of all of Houbolt's material because of the pertinence of this work to the Mercury Mark II program and other programs then under consideration.

1961 October - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Titan II to be selected as the launch vehicle for NASA's advanced Mercury. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Martin Company received informal indications from the Air Force that Titan II would be selected as the launch vehicle for NASA's advanced Mercury. Martin, Air Force, and NASA studied the feasibility of modifying complex 19 at Cape Canaveral from the Titan weapon system configuration to the Mercury Mark II launch vehicle configuration.

1961 October 27 - .

- James A. Chamberlin expects approval of the Mark II spacecraft program within 30 days. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

James A. Chamberlin, Chief of Space Task Group (STG) Engineering Division, expecting approval of the Mark II spacecraft program within 30 days, urged STG Director Robert R. Gilruth to begin reorienting McDonnell, the proposed manufacturer, to the new program. To react quickly once the program was approved, McDonnell had to have an organization set up, personnel assigned, and adequate staffing ensured. Chamberlin suggested an amendment to the existing letter contract under which McDonnell had been authorized to procure items for Mercury Mark II. This amendment would direct McDonnell to devote efforts during the next 30 days to organizing and preparing to implement its Mark II role.

1961 October 27 - .

- Program of manned spaceflight for 1963-1965. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Low, George.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Space Task Group (STG), assisted by George M. Low, NASA Assistant Director for Space Flight Operations, and Warren J. North of Low's office, prepared a project summary presenting a program of manned spaceflight for 1963-1965. This was the final version of the Project Development Plan, work on which had been initiated August 14. Additional Details: here....

1961 November 1 - .

- Space Task Group's Engineering Division briefed Seamans on the Mercury Mark II proposal. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Space Task Group's Engineering Division Chief James A. Chamberlin and Director Robert R. Gilruth briefed NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., at NASA Headquarters on the Mercury Mark II proposal. Specific approval was not granted, but Chamberlin and Gilruth left Washington convinced that program approval would be forthcoming.

1961 November 15 - .

- McDonnell submitted to Manned Spacecraft Center the detail specification of the Mercury Mark II spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Ejection,

Gemini Fuel Cell.

McDonnell submitted to Manned Spacecraft Center the detail specification of the Mercury Mark II spacecraft. A number of features closely resembled those of the Mercury spacecraft. Among these were the aerodynamic shape, tractor rocket escape tower, heatshield, impact bag to attenuate landing shock, and the spacecraft-launch vehicle adapter. Salient differences from the Mercury concept included housing many of the mission-sustaining components in an adapter that would be carried into orbit rather than being jettisoned following launch, bipropellant thrusters to effect orbital maneuvers, crew ejection seats for emergency use, onboard navigation system (inertial platform, computers, radar, etc.), and fuel cells as electrical power source in addition to silver-zinc batteries. The long-duration mission was viewed as being seven days.

1961 November 20 - .

- North American to proceed with the Paraglider Development Program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

Manned Spacecraft Center notified North American to proceed with Phase II-A of the Paraglider Development Program. A letter contract, NAS 9-167, followed on November 21; contract negotiations were completed February 9, 1962; and the final contract was awarded on April 16, 1962. Phase I, the design studies that ran from the beginning of June to mid-August 1961, had already demonstrated the feasibility of the paraglider concept. Phase II-A, System Research and Development, called for an eight-month effort to develop the design concept of a paraglider landing system and to determine its optimal performance configuration. This development would lay the groundwork for Phase II, Part B, comprising prototype fabrication, unmanned and manned flight testing, and the completion of the final system design. Ultimately Phase III-Implementation-would see the paraglider being manufactured and pilots trained to fly it.

1961 November 20 - .

- Vigorous high priority rendezvous development effort needed. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Rosen, Milton.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Milton W. Rosen, Director of Launch Vehicles and Propulsion in NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight, presented recommendations on rendezvous to D. Brainerd Holmes, Director of Manned Space Flight. The working group Rosen chaired had completed a two-week study of launch vehicles for manned spaceflight, examining most intensively the technical and operational problems posed by orbital rendezvous. Because the capability for rendezvous in space was essential to a variety of future missions, the group agreed that 'a vigorous high priority rendezvous development effort must be undertaken immediately.' Its first recommendation was that a program be instituted to develop rendezvous capability on an urgent basis.

1961 November 28-29 - .

- Phase II-A of the Paraglider Development Program discussed. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

Representatives of the Space and Information Systems Division of North American, Langley Research Center, Flight Research Center (formerly High Speed Flight Station), and Manned Spacecraft Center met to discuss implementing Phase II-A of the Paraglider Development Program. They agreed that paraglider research and development would be oriented toward the Mercury Mark II project and that paraglider hardware and requirements should be compatible with the Mark II spacecraft. Langley Research Center would support the paraglider program with wind tunnel tests. Flight Research Center would oversee the paraglider flight test program. Coordination of the paraglider program would be the responsibility of Manned Spacecraft Center.

1961 December 5 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Titan II for the Mercury Mark II - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: McNamara.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Recommendation that the weapon system of the Titan II, with minimal modifications, be approved for the Mercury Mark II rendezvous mission. On the basis of a report of the Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group, Robert C. Seamans, Jr., NASA Associate Administrator, and John H. Rubel, Department of Defense Deputy Director for Defense Research and Engineering, recommended to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara that the weapon system of the Titan II, with minimal modifications, be approved for the Mercury Mark II rendezvous mission. The planning group had first met in August 1961 to survey the Nation's launch vehicle program and was recalled in November to consider Titan II, Titan II-1/2, and Titan III. On November 16, McNamara and NASA Administrator James E. Webb had also begun discussing the use of Titan II.

1961 December 6 - .

- Preliminary project plan for the Mercury Mark II program - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Holmes, Brainard,

Seamans.

Spacecraft Bus: Gemini.

Spacecraft: Gemini LOR.

D. Brainerd Holmes, NASA Director of Manned Space Flight, outlined the preliminary project development plan for the Mercury Mark II program in a memorandum to NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. The primary objective of the program was to develop rendezvous techniques; important secondary objectives were long-duration flights, controlled land recovery, and astronaut training. The development of rendezvous capability, Holmes stated, was essential:

- It offered the possibility of accomplishing a manned lunar landing earlier than by direct ascent.

- The lunar landing maneuver would require the development of rendezvous techniques regardless of the operational mode selected for the lunar mission.

- Rendezvous and docking would be necessary to the Apollo orbiting laboratory missions planned for the 1965-1970 period.

1961 December 6 - .

- Procurement plan for the Mark II spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Holmes, Brainard.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Robert R. Gilruth, Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, transmitted the procurement plan for the Mark II spacecraft to NASA Headquarters for approval. This included scope of work, plans, type of contract administration, contract negotiation and award plan, and schedule of procurement actions. At Headquarters, D. Brainerd Holmes, Director of Manned Space Flight, advised Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., that the extended flight would be conducted in the last half of calender year 1963 and that the rendezvous flight tests would begin in early 1964. Because of short lead time available to meet the Mark II delivery and launch schedules, it was requested that fiscal year 1962 funds totaling $75.8 million be immediately released to Manned Spacecraft Center in preparation for the negotiation of contracts for the spacecraft and for the launch vehicle modifications and procurements.

1961 December 7 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- DOD/NASA coordination for Mercury Mark II - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: McNamara,

Seamans,

Webb.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., and DOD Deputy Director of Defense Research and Engineering John H. Rubel recommended to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and NASA Administrator James E. Webb that detailed arrangements for support of the Mercury Mark II spacecraft and the Atlas-Agena vehicle used in rendezvous experiments be planned directly between NASA's Office of Manned Space Flight and the Air Force and other DOD organizations. NASA's primary responsibilities would be the overall management and direction for the Mercury Mark II/ Agena rendezvous development and experiments. The Air Force responsibilities would include acting as NASA contractor for the Titan II launch vehicle and for the Atlas-Agena vehicle to be used in rendezvous experiments. DOD's responsibilities would include assistance in the provision and selection of astronauts and the provision of launch, range, and recovery support, as required by NASA.

1961 December 7 - .

- NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., approved the Mark II project development plan. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

The document approved was accompanied by a memorandum from Colonel Daniel D. McKee of NASA Headquarters stressing the large advances possible in a short time through the Mark II project and their potential application in planned Apollo missions, particularly the use of rendezvous techniques to achieve manned lunar landing earlier than direct ascent would make possible.

1961 December 7 - .

- Recommendations to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara on the division of effort between NASA and DOD in the Mark II program. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: McNamara.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Recommendations to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara on the division of effort between NASA and DOD in the Mark II program. NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., and John H. Rubel, Department of Defense (DOD) Deputy Director for Defense Research and Engineering, offered recommendations to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara on the division of effort between NASA and DOD in the Mark II program. They stressed NASA's primary responsibility for managing and directing the program, although attaining the program objectives would be facilitated by using DOD (especially Air Force) resources in a contractor relation to NASA. In addition, DOD personnel would aquire useful experience in manned spaceflight design, development, and operations. Space Systems Division of Air Force Systems Command became NASA's contractor for developing, procuring, and launching Titan II and Atlas-Agena vehicles for the Mark II program.

1961 December 7 - .

- NASA announced plans to develop a two-man Mercury capsule. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Gilruth.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

In Houston, Director Robert R. Gilruth of Manned Spacecraft Center announced plans to develop a two-man Mercury capsule. Built by McDonnell, it would be similar in shape to the Mercury capsule but slightly larger and from two to three times heavier. Its booster would be a modified Titan II. A major program objective would be orbital rendezvous. The two-man spacecraft would be launched into orbit and would attempt to rendezvous with an Agena stage put into orbit by an Atlas. Total cost of 12 capsules plus boosters and other equipment was estimated at $500 million. The two-man flight program would begin in the 1963-1964 period with several unmanned ballistic flights to test overall booster-spacecraft compatibility and system engineering. Several manned orbital flights would follow. Besides rendezvous flybys of the target vehicle, actual docking missions would be attempted in final flights. The spacecraft would be capable of missions of a week or more to train pilots for future long-duration circumlunar and lunar landing flights. The Mercury astronauts would serve as pilots for the program, but additional crew members might be phased in during the latter portions of the program.

1961 December 11 - .

- Guidelines for the development of the two-man spacecraft - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini ECS,

Gemini Ejection.

NASA laid down guidelines for the development of the two-man spacecraft in a document included as Exhibit "A" in NASA's contract with McDonnell. The development program had five specific objectives: (1) performing Earth-orbital flights lasting up to 14 days, (2) determining the ability of man to function in a space environment during extended missions, (3) demonstrating rendezvous and docking with a target vehicle in Earth orbit as an operational technique, (4) developing simplified countdown procedures and techniques for the rendezvous mission compatible with spacecraft launch vehicle and target vehicle performance, and (5) making controlled land landing the primary recovery mode. The two-man spacecraft would retain the general aerodynamic shape and basic systems concepts of the Mercury spacecraft but would also include several important changes: increased size to accommodate two astronauts; ejection seats instead of the escape tower; an adapter, containing special equipment not needed for reentry and landing, to be left in orbit; housing of most system hardware outside the pressurized compartment for ease of access; modular systems design rather than integrated; spacecraft systems for orbital maneuvering and docking; and a system for controlled land landing. Target date for completing the program was October 1965.

1961 December 12 - .

- Air Force / NASA working group to draft agreement on responsibilities in the Mercury Mark II program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Colonel Daniel D. McKee of NASA Headquarters compiled instructions for an Air Force and NASA ad hoc working group established to draft an agreement on the respective responsibilities of the two organizations in the Mark II program. Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) Director Robert R. Gilruth assigned his special assistant, Paul E. Purser, to head the MSC contingent.

1961 December 15 - .

- McDonnell given letter contract for Gemini - . Nation: USA. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Gemini. McDonnell given letter contract for development of Gemini..

1961 December 22 - .

- McDonnell Gemini Contract. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

A week after receiving it, McDonnell accepted Letter Contract NAS 9-170 to 'conduct a research and development program which will result in the development to completion of a Two-Man Spacecraft.' McDonnell was to design and manufacture 12 spacecraft, 15 launch vehicle adapters, and 11 target vehicle docking adapters, along with static test articles and all ancillary hardware necessary to support spacecraft operations. Major items to be furnished by the Government to McDonnell to be integrated into the spacecraft were the paraglider, launch vehicle and facilities, astronaut pressure suits and survival equipment, and orbiting target vehicle. The first spacecraft, with launch vehicle adapter, was to be ready for delivery in 15 months, the remaining 11 to follow at 60-day intervals. Initial Government obligation under the contract was $25 million.

1961 December 28 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Titan 2 first ground test. - .

Nation: USA.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Gemini.

Titan II, an advanced ICBM and the booster designated for NASA's two-man orbital flights, was successfully captive-fired for the first time at the Martin Co.'s Denver facilities. The test not only tested the flight vehicle but the checkout and launch equipment intended for operational use.

1961 December 29 - .

- NASA and Department of Defense roles in Gemini defined. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Holmes, Brainard,

Schriever.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

NASA issued the Gemini Operational and Management Plan, which outlined the roles and responsibilities of NASA and Department of Defense in the Gemini (Mercury Mark II) program. NASA would be responsible for overall program planning, direction, systems engineering, and operation-including Gemini spacecraft development; Gemini/Agena rendezvous and docking equipment development; Titan II/Gemini spacecraft systems integration; launch, flight, and recovery operations; command, tracking, and telemetry during orbital operations; and reciprocal support of Department of Defense space projects and programs within the scope of the Gemini program. Department of Defense would be responsible for: Titan II development and procurement, Atlas procurement, Agena procurement, Atlas-Agena systems integration, launch of Titan II and Atlas-Agena vehicles, range support, and recovery support. A slightly revised version of the plan was signed in approval on March 27 by General Bernard A. Schriever, Commander, Air Force Systems Command, for the Air Force, and D. Brainerd Holmes, Director of Manned Space Flight, for NASA.

1962 January 3 - .

- "Gemini" became the official designation of the Mercury Mark II program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

The name had been suggested by Alex P. Nagy of NASA Headquarters because the twin stars Castor and Pollux in constellation Gemini (the Twins) seemed to him to symbolize the program's two-man crew, its rendezvous mission, and its relation to Mercury. Coincidentally, the astronomical symbol (II) for Gemini, the third constellation of the zodiac, corresponded neatly to the Mark II designation.

1962 January 11 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Gemini Launch Vehicle Directorate established. - . Spacecraft: Gemini. Headquarters Space Systems Division established the Gemini Launch Vehicle Directorate (SSVL) under Colonel R.C. Dineen as part of the Deputy for Launch Vehicles (SSV)..

1962 January 15 - .

- James A. Chamberlin named Manager of Gemini Project Office (GPO). - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Chamberlin,

Gilruth.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Director Robert R. Gilruth of Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) appointed James A. Chamberlin, Chief of Engineering Division, as Manager of Gemini Project Office (GPO). The next day MSC advised McDonnell, by amendment No. 1 to letter contract NAS 9-170, that GPO had been established. It was responsible for planning and directing all technical activities and all contractor activities within the scope of the contract.

1962 January 19 - . LV Family: Titan.

- Contract for 15 Titan Gemini Launch Vehicles - . Spacecraft: Gemini. The Martin Marietta Corporation was awarded a letter contract for the development and production of 15 Titan Gemini Launch Vehicles and related aerospace ground equipment (AGE)..

1962 January 22 - .

- Gemini Program Planning Board. - . Related Persons: , McNamara. Spacecraft: Gemini. NASA Administrator James E. Webb and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara announced the NASA-DoD agreement setting up the Gemini Program Planning Board. The provisions for the Gemini program previously agreed upon were reaffirmed..

1962 January 23 - .

- Power sources for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Fuel Cell.

Manned Spacecraft Center completed an analysis of possible power sources for the Gemini spacecraft. Major competitors were fuel cells and solar cells. Although any system selected would require much design, development, and testing effort, the fuel cell designed by General Electric Company, West Lynn, Massachusetts, appeared to offer decided advantages in simplicity, weight, and compatiblity with Gemini requirements over solar cells or other fuel cells. A basic feature of the General Electric design, and the source of its advantages over its competitors, was the use of ion-exchange membranes rather than gas-diffusion electrodes. On March 20, 1962, McDonnell let a $9 million subcontract to General Electric to design and develop fuel cells for the Gemini spacecraft.

1962 January 31 - .

- 11 Atlas-Agenas rendezvous targets requested for Project Gemini. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Radar.

Manned Spacecraft Center notified Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama (which was responsible for managing NASA's Agena Programs) that Project Gemini required 11 Atlas-Agenas as rendezvous targets and requested Marshall to procure them. The procurement request was accompanied by an Exhibit 'A' describing proposed Gemini rendezvous techniques and defining the purpose of Project Gemini as development and demonstrating Earth-orbit rendezvous techniques as early as possible. If feasible, these techniques could provide a practical base for lunar and other deep space missions. Exhibit B to the purchase request was a Statement of Work for Atlas-Agena vehicles to be used in Project Gemini. Air Force Space Systems Division, acting as a NASA contractor, would procure the 11 vehicles required. Among the modifications needed to change the Atlas-Agena into the Agena rendezvous vehicle were: incorporation of radar and visual navigation and tracking aids; main engines capable of multiple restarts; addition of a secondary propulsion system, stabilization system, and command system; incorporation of an external rendezvous docking unit; and provision of a jettisonable aerodynamic fairing to enclose the docking unit during launch. The first rendezvous vehicle was to be delivered to the launch site in 20 months, with the remaining 10 to follow at 60-day intervals.

1962 February 13-15 - .

- Technical aspects of earth orbit rendezvous meeting - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Geissler,

Rudolph.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

A meeting on the technical aspects of earth orbit rendezvous was held at NASA Headquarters. Representatives from various NASA offices attended: Arthur L. Rudolph, Paul J. DeFries, Fred L. Digesu, Ludie G. Richard, John W. Hardin, Jr., Ernst D. Geissler, and Wilson B. Schramm of Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC); James T. Rose of MSC; Friedrich O. Vonbun, Joseph W. Siry, and James J. Donegan of Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC); Douglas R. Lord, James E. O'Neill, Richard J. Hayes, Warren J. North, and Daniel D. McKee of the NASA Office of Manned Space Flight (OMSF). Joseph F. Shea, Deputy Director for Systems, OMSF, who had called the meeting, defined in general terms the goal of the meeting: to achieve agreement on the approach to be used in developing the earth orbit rendezvous technique. After two days of discussions and presentations, the Group approved conclusions and recommendations:

- Gemini rendezvous operations could and must provide substantial experience with rendezvous techniques pertinent to Apollo.

- Incorporation of the Saturn guidance equipment in a scaled-down docking module for the Agenas in the Gemini program was not required.

- Complete development of the technique and equipment for Apollo rendezvous and docking should be required before the availability of the Saturn C-5 launch vehicle.

- Full-scale docking equipment could profitably be developed by three- dimensional ground simulations. MSFC would prepare an outline of such a program.

- The Apollo rendezvous technique and actual hardware could be flight- tested with the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle. MSFC would prepare a proposed flight test program.

- The choice of connecting or tanking modes must be made in the near future. The MSFC Orbital Operations Study program should be used to provide data to make this decision.

- The rendezvous technique which evolved from this meeting would place heavy requirements on the ground tracking network. GSFC should provide data relating the impact of detailed trajectory considerations to ground tracking station requirements.

1962 February 19 - .

- AiResearch received subcontract to manufacture the environmental control system (ECS) for Gemini. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini ECS.

AiResearch Manufacturing Company, a division of the Garrett Corporation, Los Angeles, California, received a $15 million subcontract from McDonnell to manufacture the environmental control system (ECS) for the Gemini spacecraft. This was McDonnell's first purchase order on behalf of the Gemini contract. Patterned after the ECS used in Project Mercury (also built by AiResearch), the Gemini ECS consisted of suit, cabin, and coolant circuits, and an oxygen supply, all designed to be manually controlled whenever possible during all phases of flight. Primary functions of the ECS were controlling suit and cabin atmosphere, controlling suit and equipment temperatures, and providing drinking water for the crew and storage or disposal of waste water.

1962 February 22 - . LV Family: Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan II.

- Proposal for redundant subsystems for the Gemini launch vehicle. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Inertial Guidance System.

Martin-Baltimore submitted its initial proposal for the redundant flight control and hydraulic subsystems for the Gemini launch vehicle; on March 1, Martin was authorized to proceed with study and design work. The major change in the flight control system from Titan II missile to Gemini launch vehicle was substitution of the General Electric Mod IIIG radio guidance system (RGS) and Titan I three-axis reference system for the Titan II inertial guidance system. Air Force Space Systems Division issued a letter contract to General Electric Company, Syracuse, New York, for the RGS on June 27. Technical liaison, computer programs, and ground-based computer operation and maintenance were contracted to Burroughs Corporation, Paoli, Pennsylvania, on July 3.

1962 February 24 - .

- Subcontract for the liquid propulsion systems for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini OAMS/RCS.

McDonnell let a $32 million subcontract to North American Aviation's Rocktdyne Division, Sacramento, California, to build liquid propulsion systems for the Gemini spacecraft. Two separate systems were required: the orbit attitude and maneuvering system (OAMS) and the reaction or reentry control system (RCS). The OAMS, located in the adapter section, had four functions: (1) providing the thrust required to enable the spacecraft to rendezvous with the target vehicle; (2) controlling the attitude of the spacecraft in orbit; (3) separating the spacecraft from the second stage of the launch vehicle and inserting it in orbit; and (4) providing abort capability at altitudes between 300,000 feet and orbital insertion. The OAMS initially comprised 16 ablative thrust chambers; eight 25-pound thrusters to control the spacecraft attitude in pitch, yaw, and roll axes; and eight 100-pound thrusters to maneuvre the spacecraft axially, vertically, and laterally. Rather than providing a redundant system, only critical components were to be duplicated. The RCS was located forward of the crew compartment in an independent RCS module. It consisted of two completely independent systems, each containing eight 25-pound thrusters very similar to those used in the OAMS. Purpose of the RCS was to maintain the attitude of the spacecraft during the reentry phase of the mission.

1962 February 28 - .

- Interface between Gemini spacecraft and paraglider. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

Representatives of McDonnell, North American, Manned Spacecraft Center, and NASA Headquarters met to begin coordinating the interface between spacecraft and paraglider. The first problem was to provide adequate usable stowage volume for the paraglider landing system within the spacecraft. The external geometry of the spacecraft had already been firmly established, so the problem narrowed to determining possible volumetric improvements within the spacecraft's recovery compartment.

1962 March 5 - .

- Proposed training devices for Project Gemini. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Paraglide.

Harold I. Johnson, Head of the Spacecraft Operations Branch of Manned Spacecraft Center's Flight Crew Operations Division, circulated a memorandum on proposed training devices for Project Gemini. A major part of crew training depended on several different kinds of trainers and simulators corresponding to various aspects of proposed Gemini missions. Overall training would be provided by the flight simulator, capable of simulating a complete mission profile including sight, sound, and vibration cues. Internally identical to the spacecraft, the flight simulator formed part of the mission simulator, a training complex for both flight crews and ground controllers that also included the mission control center and remote site displays. Training for launch and re-entry would be provided by the centrifuge at the Naval Air Development Center, Johnsville, Pennsylvania. A centrifuge gondola would be equipped with a mock-up of the Gemini spacecraft's interior. A static article spacecraft would serve as an egress trainer, providing flight crews with the opportunity to practice normal and emergency methods of leaving the spacecraft after landings on either land or water. To train flight crews in land landing, a boilerplate spacecraft equipped with a full-scale paraglider wing would be used in a flight program consisting of drops from a helicopter. A docking trainer, fitted with actual docking hardware and crew displays and capable of motion in six degrees of freedom, would train the flight crew in docking operations. Other trainers would simulate major spacecraft systems to provide training in specific flight tasks.

1962 March 5 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas SLV-3 Agena D.

- Rendezvous radar and transponder system for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Radar,

Gemini Agena Target Vehicle.

Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Baltimore, Maryland, received a $6.8 million subcontract from McDonnell to provide the rendezvous radar and transponder system for the Gemini spacecraft. Purpose of the rendezvous radar, sited in the recovery section of the spacecraft, was to locate and track the target vehicle during rendezvous maneuvers. The transponder, a combined receiver and transmitter designed to transmit signals automatically when triggered by an interrogating signal, was located in the Agena target vehicle.

1962 March 7 - .

- Subcontract to Honeywell to provide attitude control and maneuvering electronics system for Gemini. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini OAMS/RCS.

McDonnell awarded a $6.5 million subcontract to Minneapolis-Honeywell Regulator Company, Minneapolis, Minnesota, to provide the attitude control and maneuvering electronics system for the Gemini spacecraft. This system commanded the spacecraft's propulsion systems, providing the circuitry which linked the astronaut's operation of his controls to the actual firing of thrusters in the orbit attitude and maneuvering system or the reaction control system.

1962 March 8 - .

- North American to develop an emergency parachute recovery system for flight test vehicles of the Paraglider Development Program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Parachute,

Gemini Paraglide.

North American to develop an emergency parachute recovery system for flight test vehicles of the Paraglider Development Program. Manned Spacecraft Center directed North American to design and develop an emergency parachute recovery system for both the half-scale and full-scale flight test vehicles required by Phase II-A of the Paraglider Development Program. They further authorized North American to subcontract the emergency recovery system to Northrop Corporation's Radioplane Division, Van Nuys, California. North American awarded the $225,000 subcontract to Radioplane on March 16. This was one of two major subcontracts led by North American for Phase II-A. The other, for $227,000, went to Goodyear to study materials and test fabrics for inflatable structures.

1962 March 14 - .

- Gemini seat ejection to be initiated manually. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Ejection,

Gemini Parachute.

Gemini Project Office (GPO) decided that seat ejection was to be initiated manually, with the proviso that the design must allow for the addition of automatic initiation if this should later become a requirement. Both seats had to eject simultaneously if either seat ejection system was energized. The ejection seat was to provide the crew a means of escaping from the Gemini spacecraft in an emergency while the launch vehicle was still on the launch pad, during the initial phase of powered flight (to about 60,000 feet), or in case of paraglider failure after reentry. In addition to the seat, the escape system included a hatch actuation system to open the hatches before ejection, a rocket catapult to propel the seat from the spacecraft, a personnel parachute system to sustain the astronaut after his separation from the seat, and survival equipment for the astronaut's use after landing. At a meeting on March 29, representatives of McDonnell, GPO, Life Systems Division, and Flight Crew Operations Division agreed that a group of specialists should get together periodically to monitor the development of the ejection seat, its related components, and the attendant testing. Although ejection seats had been widely used in military aircraft for years, Gemini requirements, notably for off-the-pad abort capability, were beyond the capabilities of existing flight-qualified systems. McDonnell awarded a $1.8 million subcontract to Weber Aircraft at Burbank, California, a division of Walter Kidde and Company, Inc, for the Gemini ejection seats on April 9; a $741,000 subcontract went to Rocker Power, Inc., Mesa, Arizona, on May 15 for the escape system rocket catapult.

1962 March 17 - .

- McDonnell awarded AiResearch a $5.5 million subcontract to provide the reactant supply system for the Gemini spacecraft fuel cells. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Fuel Cell.

McDonnell awarded AiResearch a $5.5 million subcontract to provide the reactant supply system for the Gemini spacecraft fuel cells. The oxygen and hydrogen required by the fuel cell were stored in two double-walled, vacuum-insulated, spherical containers located in the adapter section of the spacecraft. Reactants were maintained as single-phase fluids (neither gas nor liquid) in their containers by supercritical pressures at cryogenic temperatures. Heat exchangers converted them to gaseous form and supplied them to the fuel cells at operating temperatures.

1962 March 19 - .

- Horizon sensor system contract for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Inertial Guidance System.

Advanced Technology Laboratories, Inc, Mountain View, California, received a $3.2 million subcontract from McDonnell to provide the horizon sensor system for the Gemini spacecraft. Two horizon sensors, one primary and one standby, were part of the spacecraft's guidance and control system. They scanned, detected, and tracked the infrared radiation gradient between Earth and space (Earth's infrared horizon) to provide reference signals for aligning the inertial platform and error signals to the attitude control and maneuver electronics for controlling the spacecraft's attitude and its pitch and roll axes.

1962 March 19 - .

- Contract for the retrograde rockets for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Thiokol Chemical Corporation, Elkton, Maryland, received a $400,000 sub-contract from McDonnell to provide the retrograde rockets for the Gemini spacecraft. Only slight modification of a motor already in use was planned, and a modest qualification program was anticipated. Primary function of the solid-propellant retrorockets, four of which were located in the adapter section, was to decelerate the spacecraft at the start of the reentry maneuver. A secondary function was to accelerate the spacecraft to aid its separation from the launch vehicle in a high-altitude, suborbital abort.

1962 March 21 - . LV Family: Titan.

- Contract for Titan Gemini engines - . Spacecraft: Gemini. Aerojet-General Corporation was given a letter contract for research, development, and manufacture of 15 sets of Titan Gemini Launch Vehicle propulsion systems and associated ground equipment..

1962 March 21 - .

- Gemini digital command system. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Inertial Guidance System.

McDonnell awarded a $4.475 million subcontract to the Western Military Division of Motorola, Inc, Scottsdale, Airzona, to design and build the digital command system (DCS) for the Gemini spacecraft. Consisting of a receiver/decoder package and three relay packages, the DCS received digital commands transmitted from ground stations, decoded them and transferred them to the appropriate spacecraft systems. Commands were of two types: real-time commands to control various spacecraft functions and stored program commands to provide data updating the time reference system and the digital computer.

1962 March 28 - .

- Voice communications systems for Gemini - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

McDonnell awarded a $2.5 million subcontract to Collins Radio Company, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to provide the voice communications systems for the Gemini spacecraft. Consisting of the voice control center on the center instrument panel of the spacecraft, two ultrahigh-frequency voice transceivers, and one high-frequency voice transceiver, this system provided communications between astronauts, between the blockhouse and the spacecraft during launch, between the spacecraft and ground stations from launch through reentry, and between the spacecraft and recovery forces after landing.

1962 March 29 - .

- Inertial measuring unit for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Inertial Guidance System.

The St. Petersburg, Florida, Aeronautical Division of Minneapolis-Honeywell received an $18 million subcontract from McDonnell to provide the inertial measuring unit (IMU) for the Gemini spacecraft. The IMU was a stabilized inertial platform including an electronic unit and a power supply. Its primary functions were to provide a stable reference for determining spacecraft attitude and to indicate changes in spacecraft velocity.

1962 March 31 - .

- The configuration of the Gemini spacecraft was formally frozen. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Following receipt of the program go-ahead on December 22, 1961, McDonnell began defining the Gemini spacecraft. At that time, the basic configuration was already firm. During the three-month period, McDonnell wrote a series of detailed specifications to define the overall vehicle, its performance, and each of the major subsystems. These were submitted to NASA and approved. During the same period, the major subsystems specification control drawings - the specifications against which equipment was procured - were written, negotiated with NASA, and distributed to potential subcontractors for bid.

1962 April 3 - .

- Participation of Ames in the Gemini wind tunnel program. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini.

Representatives of Manned Spacecraft Center, Ames Research Center, Martin, and McDonnell met to discuss the participation of Ames in the Gemini wind tunnel program. The tests were designed to determine: (1) spacecraft and launch vehicle loads and the effect of the hatches on launch stability, using a six percent model of the spacecraft and launch vehicle; (2) the effect of large angles of attach, Reynold's number, and retrorocket jet effects on booster tumbling characteristics and attachment loads; (3) exit characteristics of the spacecraft; and (4) reentry characteristics of the reentry module.

1962 April 7 - .

- C- and S-band radar beacons for the Gemini spacecraft. - .

Nation: USA.

Spacecraft: Gemini,

Gemini Radar.