Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Korolev, Sergei Pavlovich

Korolev, 1946 Credit: © Mark Wade |

Born: 1907-01-12. Died: 1966-01-14. Birth Place: Zhitomir.

Korolev created the first Soviet rockets and spacecraft. He was portrayed for years as a legendary, iconographic figure that single-handedly was responsible for the early Soviet victories in the space race. He was singularly responsible for creating the first long range ballistic missiles, the first space launchers, the first artificial satellite, and putting the first man in space. His premature death led to his name and accomplishments being made public, while those of other chief designers of rockets and satellites remained secret. This resulted in an exaggerated perception that he occupied a uniquely central position in rocketry and spaceflight. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union the lives and roles of other important figures in Soviet became known in great detail. In the process a more balanced view of Korolev became possible.

Korolev's story was inextricably bound up in the deep passions and resentments of the three titans of Soviet space rocketry - Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, Vladimir Nikolayev Chelomei, and Valentin Petrovich Glushko. Each had his own patrons in the Kremlin hierarchy and Politburo. Each had been deeply scarred and mishandled by the Soviet system. Each was very sure that his technical and management approach was superior. The depth of their passions in their struggle for ascendancy can scarcely be imagined.

Korolev was born to a Russian literature teacher in the town of Zhitomir in the Ukraine. He was fascinated with aircraft at an early age and became a pilot. At the age of 17 he had designed his first glider, the K-5. After attending the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, he went on to the Moscow Higher Technical University (MVTU). There he was involved in design and construction of an increasingly ambitious series of gliders, culminating in the SK-4, designed for record duration flights in the stratosphere. He became interested in the possibilities of rocket-propelled aircraft and in September 1931, together with Tsander, founded the Moscow rocketry organization GIRD (Group for Investigation of Reactive Motion).

Similar efforts were underway abroad. In America the secretive Robert Goddard had already flown his first liquid propellant rockets. In Germany the VfR (Verein fuer Raumschiffahrt - Society for Spaceship Travel) was testing liquid fuelled rockets of increasing size. The VfR collapsed in 1933 as its members chose to leave the country or begin work for the Nazi government. The members that remained finally developed the A-4 (V-2) missile, the basis for all liquid fuel rockets to follow. In America the potential of his Goddard's work was unrecognized. He finally had to close up his New Mexico test range and develop small auxiliary rockets for the Navy.

In Russia, GIRD was launching the Soviet Union's first liquid-propelled rockets, the GIRD-9 and GIRD-10. GIRD lasted only two years before the military, seeing the potential of rockets, replaced it with the RNII (Reaction Propulsion Scientific Research Institute). Glushko was brought from Leningrad to head rocket engine design at RNII, while Korolev was in charge of airframes. They developed a series of rocket-propelled missiles and gliders during the 1930's, culminating in Korolev's RP-318, Russia's first rocket propelled manned aircraft, powered by Glushko's ORM-65 rocket engine.

Before the aircraft could make a rocket propelled flight, Korolev and Glushko were thrown into the Soviet prison system in 1938 during the peak of Stalin's insane purges. Glushko was arrested on March 23. Korolev, denounced by Glushko, was arrested on June 7 and sentenced to ten years hard labor on 27 September. He spent On 10 July 1940 he was sentenced to work in the Kolyma gold mines, a virtual death sentence to the most dreaded part of the Gulag. However Stalin had recognized the importance of aeronautical engineers in preparing for the impending war with Hitler. A system of sharashkas (prison design bureaus) was set up to exploit jailed talent. Korolev was saved by the intervention of senior aircraft designer Sergei Tupolev, himself a prisoner, who requested his services in the TsKB-39 sharashka. In September 1940, his health already ruined, he was transferred to work at Tupolev's bureau in Moscow. Korolev was not allowed to work on rockets except at night on his own time. His RP-318 had flown on 28 February 1940, without his involvement.

In 1942, after Tupolev's team was evacuated to Omsk, Korolev was transferred to TsKB-16 in Kazan where he served as Deputy Director for Flight Testing (although still officially a prisoner). Here he was able to return to development of rockets for aircraft and missile propulsion. In November 1944 Korolev was given charge of a team of 60 engineers and required to provide a draft project for a Soviet counterpart to the V-2 within three days. The resulting two-stage design used Lox/Alcohol propellants and an autopilot for guidance. These designs evolved into the more refined D-1 and D-2 rockets with a 75 km range.

With the war over, the immense progress that the Von Braun team had made in rocketry became apparent. Provided nearly unlimited funds, the Germans had developed the 300 km range V-2 missile, which was a decade ahead of the Soviet designs. The Russian engineers that first inspected the recovered remains of a V-2 called it ‘that which cannot be'.

Stalin, fascinated with the technology, was quite annoyed that the Peenemuende team had gone over to the Americans and that American intelligence had managed to loot most of the V-2 factories and rockets, even in the Russian zone. Russian teams were sent seize available equipment and information as early as April 1945. Korolev was released from the Kazan sharashka and was in Germany from August 1945. At first he merely accompanying the team that salvaged what was left. He was present (under guard, outside the fence, while Glushko was part of the official delegation inside) at the British 'Operation Backfire' launch of a V-2 from Altenwaide on 15 October 1945. He interviewed dozens of V-2 engineers and technicians still in Germany.

On May 13, 1946 Stalin signed the decree beginning development of Soviet ballistic missiles. The Minister of Armaments, Dmitri Fedorovich Ustinov, was put in charge. In August 1946, the Scientific Research Institute NII-88 was established to copy the V-2 missile. Although not fully rehabilitated, Korolev's piercing personality and organizational abilities had clearly been impressive, and Ustinov personally appointed him Chief Constructor NII-88. Glushko was named head of GDL-OKB to design engines for Korolev's rockets. Following Korolev's selection, 234 German employees of the Mittelwerke V-2 factory were rounded up on the night of 22-23 October 1946 and sent to relatively good living conditions at Gordodomlya on Lake Seleger, between Moscow and Leningrad. Thus the jailed became the jailer. However until he had proved himself a master of rocket technology, Korolev would be forced to have his rocket designs considered in competition with those of Groettrup's German team.

The first task was to put the V-2 into production in Russia. This was a huge undertaking -- Russian manufacturing technology was equivalent to that of Germany at the beginning of the 1930's. Before this was even underway, a competition was held for design of an improved V-2. This R-2 was designed by Korolev in 1947-1948 in competition with Groettrup's G-1. When the State Commission evaluated the designs in December 1948, the G-1 was found the superior design. Korolev fought the decision for a long time, updating his R-2 design to include some of the G-1's features. Finally the decision was reversed and Korolev's design was accepted for test. State trials flights were conducted from 21 September 1949 to July 1951.

The next competition was for a quantum leap to a 3000 km range ballistic missile. The NTS (Scientific-Technical Soviet) of NII-88 met in plenary session on 7 December 1949 and subjected Korolev's R-3 design to withering criticism. In general they preferred Groettrup's G-4/R-14 design to the same requirement. This assumed fewer technical advances in engine design but greater improvements in mass fraction reduction. After heated discussion, the Soviet approved further development of technology for the R-3, but not the missile itself.

With this decision Korolev finally caved in and adopted the German aerodynamic and engine solutions with fervor in his next designs. He put the R-3 on a slow track to oblivion. Following years of trade studies, approval came for development of an intercontinental rocket with a range of 7,000 km on 13 February 1953. Korolev used a modification of the German concept for an ICBM. What started out as Groettrup's 'cluster of G-4's' (G-5 / R-15) became the R-7 when Korolev conceived of a lengthened core sustainer stage. This would allow all engines to be ignited on the pad, eliminating the problems of air start in Groettrup's design.

The German team was aware of none of this. Members of the team began to be repatriated on 3 April 1951. By October 1951 they were completely isolated and work basically stopped. The last member of the group returned to Germany on 22 November 1953. Groettrup made it to West Germany and was debriefed by the CIA in 1957, but provided some deliberately false information and downplayed the importance of the German work in order to avoid Russian retribution. The full story did not come out until the end of the century.

In order to concentrate on development of the R-7, further IRBM development was spun off to a new design bureau in Dnepropetrovsk headed by Korolev's assistant, Mikhail Kuzmich Yangel. This was the first of several design bureaus that would be spun off from Korolev's OKB-1 bureau once a new technology had been perfected.

The R-7 faced enormous development problems. Glushko's RD-105/RD-106 rocket motors had seemingly insoluble combustion chamber instability problems. The weight of the thermonuclear warhead to be carried was increased from the 3 metric tons to 5.5 metric tons. The entire vehicle had to be scaled up proportionately, and this meant that Glushko's troublesome single-chamber engines had to be replaced by the RD-107/-108 design, a cluster of four nozzles sharing common fuel pumps. This could assure stable combustion, but greatly increased the complexity of the booster, with a total of twenty main engines and sixteen vernier engines firing at lift-off, as opposed to five engines for the RD-105/106 approach. Korolev already had reason to be dissatisfied with Glushko's performance.

Korolev's enormous drive and personal attention to detail overcame all obstacles. The R-7 was first successfully launched on 21 August 1957 and then orbited the first artificial earth satellite on 4 October 1957. The first operational satellite for the launcher was to have been the Zenit military photoreconnaissance satellite. Korolev, flushed after the success of Sputnik, instead advocated that manned spaceflight should have first priority. After bitter disputes, a compromise solution was reached. Korolev was authorized to proceed with development of a spacecraft to achieve manned flights at the earliest possible date. However the design would be such that the same spacecraft could be used to fulfill the military's unmanned photoreconnaissance satellite requirement. In November 1958 the Council of Chief designers approved the Vostok manned space program, in combination with the Zenit spy satellite program. The Vostok would put the first human being into space on 12 April 1961.

The next quantum leap was a launcher designed expressly for Soviet conquest of the planets. When the time came for the 75 metric ton payload N1 rocket in the late 1950's, Korolev again turned to German work. The N1 was the direct aerodynamic descendent of the Groettrup G-2 and G-4. It incorporated all of the essential features of Groettrup's designs - the 85-degree slope cone, topped by a cylindrical fore body and a sharply spiked nose, and the use of upper stages of the conical vehicle as smaller launch vehicles (the N11 and N111 in the case of the N1). It was only the limitations of Soviet manufacturing technology that forced Korolev to adopt the spherical tank design of the N1 in place of the integral common-bulkhead tanks of the Groettrup vehicles.

As development and production of rockets and spacecraft became an increasing part of the Soviet industry, other chief designers set their sights on getting a piece of the pie. Chelomei was the country's leading designer of cruise missiles. It was apparent that the ballistic missile, for which no defense could be developed for decades, would win out over the cruise missile as a weapon system. Chelomei was also anxious to be involved in the much more exciting area of space flight. When Korolev's R-7 experienced a long string of launch failures in the summer of 1957, Chelomei was quick to criticize Korolev and ask to be put in charge of the development. But the decisive event in getting a piece of the space action was Chelomei's hiring of Nikita Khrushchev's son, Sergei. This gave Chelomei sudden and immediate access to the highest possible patron in the hierarchy. He was rewarded with his own design bureau, OKB-52, in 1959. OKB-52 was immediately assigned several development projects in the explosion of military space and missile projects following the U-2 shoot down, the resulting collapse of the Geneva talks with Eisenhower, and Kennedy's accession to the presidency in the United States.

Kennedy had been partly elected on the basis of claims of a 'missile gap' with the Soviet Union. Russia's succession of Sputnik and Luna launches, combined with the bellicose claims of Khrushchev, created the public impression that Russia was far ahead of the United States in the fielding of unstoppable ICBM's and space weapons. In fact, Korolev's R-7, with its enormous launch pads, complex assembly and launching procedures, cryogenic liquid oxygen oxidizer, and radio-controlled guidance was a totally impractical weapon. The warhead ended up being overweight, giving it a range of only 6,800 km, barely enough to reach the northern United States. As a result, it would be deployed as a weapon at only eight launch pads at Tyuratam and Plesetsk, in the north of the country. More practical successors, Yangel's R-16 and Korolev's R-9, would not be available for years. The Eisenhower administration, thanks to the U-2 overflights, knew that the 'missile gap' did not exist, but in that curious logic that pertains to intelligence matters, would not tell the US public that it knew that the Soviet missile threat was virtually non-existent.

Nevertheless, having been elected on the basis of the existence of such a threat, and having selected the former general manager of General Motors, Robert McNamara, as his Secretary of Defence, Kennedy felt impelled to plunge into a massive program of ICBM construction. Evidently unable to think in terms of smaller numbers due to his motor industry background , McNamara chose the nice round figure of 1,000 ICBM's as a goal. The existing Atlas and Titan designs were too expensive to operate in such large numbers. Therefore the Minuteman program, already begun under Eisenhower, was expanded to provide a low-maintenance solid-fuelled missile that could be produced and cheaply operated in vast quantities.

The Russians, shocked into being drawn into an expensive arms race involving a thousand missiles as opposed to a few hundred, began development of equivalents. Korolev was tasked to build a solid-fuelled counterpart of the Minuteman, the RT-2. This new technology weapon encountered technical problems and was never fielded in any significant numbers. Khrushchev asked Chelomei to build a less risky, small liquid fuelled missile, the UR-100. This became the Soviet equivalent to the Minuteman, being built in the thousands and making Chelomei the leading rocket manufacturer in Russia. Yangel was to continue development of his R-16 into the R-36 'city-buster' missiles, which the Pentagon held up as an enormous threat during the three decades to come (although they never felt impelled to duplicate it by simply deploying more of the equivalent Titan 2).

Chelomei's ascendancy coincided with a huge technical dispute between Korolev on the one hand and Glushko on the other. Glushko had decided to quit developing rocket engines using cryogenic liquid oxygen. The use of hypergolic (self-igniting), storable oxidizer and fuel combinations had enormous operational advantages. The propellants could be put in the missile's tanks and stored for long periods. Such rockets, once fuelled, were available at any time for launch. Rockets using cryogenic liquids had to be loaded just before the launch, since the liquid oxygen quickly boiled off at normal temperatures. If a launch was delayed for more than a couple of hours, launchers using cryogenic liquids had to be defueled, and refueled again for the next attempt, leading typically to a one day recycle time before the next launch could be attempted. The drawback of the storable propellants was that they were typically very toxic and dangerously corrosive. They had to be handled very carefully in special chemical protection gear. In the case of spills, accidents, or booster explosions, a dangerous cloud of toxic gas was created and the surrounding area contaminated.

Glushko (and Chelomei, Yangel, and Makeyev) felt that the operational advantages of storable propellants outweighed the safety issues. Korolev did not, and insisted in using liquid oxygen and kerosene propellants even in missile applications. The rift was complete during development of Korolev's R-9 ICBM. Glushko only provided engines to Korolev's specifications under direct orders from the Soviet leadership. Korolev turned to Nikolai Kuznetsov's bureau, whose previous experience had been in turboprop engines, to develop engines for the later R-9 versions and the new N1 space launcher. The Soviet military sided with Glushko - it only deployed 54 of Korolev's R-9 missiles, as against 380 of Yangel's R-16 and 800 of Chelomei's UR-100 (and it should be noted, the Americans selected toxic storable propellants for their Titan 2 rocket, the French for the Ariane, and the Chinese for the Long March).

None of this gained Korolev any friends in the military. They had contributed huge sums to his R-5, R-7 and R-9 programs and he had not produced any weapons of military usefulness. Their Zenit military reconnaissance satellite, begun in 1956, was deferred after Korolev's intervention, in favor of the Vostok manned spaceflight program. He was using missiles developed with their money for the purpose of exploring outer space. While it certainly provided positive propaganda for the Communist system, it was not contributing to the security of the Soviet state.

Each chief designer therefore became identified with powerful patrons in the cliques of the Kremlin hierarchy. Korolev, and his deputy Mishin, had in their employ Yuri Semenov, the son-in-law of Politburo ideology chief Andrei Kirilenko. Glushko and Yangel, by virtue of their production of the missiles that the military actually wanted, earned the patronage of Dmitri Ustinov. Chelomei had his direct conduit to Khrushchev.

In his pursuit of his dream of manned conquest of space, Korolev divested himself of all peripheral activities. He had already passed tactical and sea-launched missiles to Makeyev, storable propellant long range missiles to Yangel, and communications and navigations satellites to Reshetnev. Korolev finally obtained approval for a Soviet manned lunar lading program in August 1964. In order to concentrate on achieving a moon landing, the remaining ‘peripheral' work of OKB-1 were spun off to others: solid propellant rockets to Nadiradze; military satellites to Kozlov in Samara; lunar and planetary probes to Babakin at Lavochkin. The overthrow of Khrushchev two months later put Chelomei out of favor and allowed Korolev to gather into his hands all manned space projects.

Korolev, despite a lack of enthusiasm in the Soviet hierarchy and a budget a fraction of the Americans, continued to engineer space triumphs. In 1964 and 1965 modifications of the Vostok were used to orbit the first multi-crew spacecraft and for the first space walk. But it was nearly the last hurrah. In 1965 the Americans began their Gemini manned space flights and began to dismantle the Soviet lead in space. Korolev's own projects were approved but required a continuous battle for resources against the higher-priority ballistic missile programs.

Korolev was diagnosed with cancer some time in 1965 but kept it a secret from his colleagues. In January 1966 he checked into a Moscow hospital. The Minister of Health himself elected to conduct the colon surgery – not his area of expertise. It all went horribly wrong, and Korolev died on the operating table. His untimely death at 59 was a huge blow to the Soviet space program. His successor, Mishin, did not have the necessary talents and standing to push Korolev's moon project through to a successful conclusion. Just two weeks after Korolev's death his Luna 9 probe soft-landed on the moon and sent back the first close-up views of the surface. It was the last significant Soviet space first.

Korolev's talents were immense vision, enthusiasm and energy that motivated his co-workers and subordinates. His personal attention to detail ensured that critical equipment was of the highest quality and that manned space flights were safely conducted. He had to be enormously persistent and convinced of the rightness of his views to push his projects forward against immense opposition and competition.

But these qualities became less appropriate as the projects increased in number and scope. Korolev's refusal to compromise on technical issues resulted in alienation of other chief designers, most notably Glushko, forcing him to lose years of time developing new sources of rocket engines. The Americans required the resources and expertise of four major contractors to develop the Saturn V booster and the Apollo spacecraft. Korolev was attempting to do the same within a single industrial enterprise. He left his successor, Mishin, with a seemingly impossible task. Then again, had he lived a few more years in good health, perhaps he could have beat the Americans to the moon…and gone on to Mars, one improvised step at a time…

| Korolev bureau Russian manufacturer of rockets, spacecraft, and rocket engines, Kaliningrad, Russia. |

Country: Russia, Ukraine. Spacecraft: Vostok, Voskhod. Projects: Luna, Venera. Agency: Korolev bureau. Bibliography: 283, 375, 5642.

| Korolev |

| Korolev |

| Korolev |

| Korolev |

| Korolev |

| Vostok 1 Gagarin with Korolev before flight. Credit: RKK Energia |

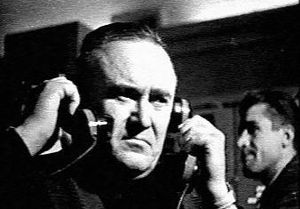

| Vostok 1 - Korolev Korolev during Vostok 1 flight. Credit: RKK Energia |

| Female cosmonauts Female cosmonauts with Korolev. Credit: RKK Energia |

| Korolev/Kurchatov Architects of the Soviet nuclear deterrent. Credit: RKK Energia |

1907 January 12 - .

- Birth of Sergei Pavlovich Korolev - . Nation: Russia, Ukraine. Related Persons: Korolev. Soviet Chief Designer, responsible for creating the first long range ballistic missiles, the first space launchers, the first artificial satellite, and putting the first man in space. After his premature death the Soviets lagged in space..

1938 March 23 - .

- Glushko arrested by Soviet secret police. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Glushko, Korolev. The leading Soviet rocket engine designer is arrested in one of Stalin's purges. Under interrogation he denounces Korolev and two others..

1938 June 7 - .

1938 September 27 - .

1939 June 13 - .

- Korolev's prison sentence reviewed by Soviet secret police. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. The NKVD secret police confirm Korolev's sentence on 28 May 1940. On 10 July 1940 he is sentenced to eight years hard labor in the Kolyma gold mines..

1940 September - .

- Korolev moved from Kolyma to Tupolev 'sharashka'. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. At the instigation of aircraft designer Tupolev, Korolev is transferred from Kolyma gold mines to a secret police 'special design bureau' - a unit consisting of imprisoned engineers..

1944 November - . Launch Vehicle: RDD.

- Korolev designs RDD - Long range rocket - in response to the German V-2. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Korolev was given charge of a team of 60 engineers and required to provide a draft project in three days. The resulting two-stage design used Lox/Alcohol propellants and an autopilot for guidance. These designs evolved into the more refined D-1 and D-2 before being overtaken by the post-war availability of V-2 technology.

1946 August 9 - . LV Family: V-2. Launch Vehicle: R-1.

- Korolev named Chief Designer for R-1 rocket (copy of German V-2). - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Ministry of Armaments Decree 83-K 'On appointment of S. P Korolev as Chief Designer of R-1' was issued..

1946 August 30 - . LV Family: V-2. Launch Vehicle: R-1.

- Korolev head of Department 3, NII-88. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Decree 'On appointment of S. P. Korolev as Chief of Department No. 3 of NII-88 SKB' was issued..

1947 May 22 - . LV Family: Groettrup. Launch Vehicle: G-1.

- Groettrup G-1 design ordered - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Glushko,

Groettrup,

Korolev.

The G-1 was Groettrup's first design after the German engineering team had been moved to Russia. The first group of 234 specialists was given the task of designing a 600 km range rocket (the G-1/R-10). Work had begun on this already in Germany but the initial challenge in Russia was that the technical documentation was somehow still 'in transit' from the Zentralwerke. The other obstacle was Russian manufacturing technology, which was equivalent to that of Germany at the beginning of the 1930's. The Germans worked at two locations, NII-88 (Korolev OKB) and Gorodmlya Island to complete the design of the G-1. Other groups of Germans worked at Factory 88 (R-1 production) and Factory 456 (Glushko OKB / engine production).

1948 December 28 - . LV Family: Groettrup. Launch Vehicle: G-1.

- G-1 and R-2 designs evaluated by Soviet State Commission. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

The team defended the G-1 draft project on 28 December 1948. The State Commission found the G-1 to be superior to Korolev's R-2 design in many respects. However the Russian designers managed to convince the government to put the R-2 rather than the G-1 into production by arguing that the manufacturing technology of the G-1 could not be mastered immediately by Soviet Union. Several of the design concepts (integrated propellant tanks, radio-controlled cut-off, forward liquid oxygen tank) were however used by the Russians in their R-2 and R-5 rockets.

1949 June - . Launch Vehicle: R-3.

- R-3 draft project completed - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. In selecting a final R-3 design, Korolev's preferred approach was a conventional single-stage design. This was down-selected within the bureau and seems to have borrowed a lot from contemporary classified US orbital rocket designs..

1949 December 7 - . Launch Vehicle: R-3.

- Groettrup G-4 IRBM evaluated against Korolev's R-3. R-3 project reformulated - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Program: Navaho.

The NTS (Scientific-Technical Soviet) of NII-88 met in plenary session and subjected Korolev's proposal to withering criticism. The G-4 was found to be superior. After heated discussion, the Soviet approved further development of technology for the R-3, but not the missile itself. The decisions were: an R-3A technology demonstrator would be built and flown under Project N-1 (probably to prove G-4 concepts). Under Project N-2 both the RD-110 and D-2 engines would proceed into development test in order to prove Lox/Kerosene propellant technology. Packet rocket and lightweight structure research for use in an ICBM would continue under project N-3 / T-1. Winged intercontinental cruise missile studies would continue under project N-3 / T-2. Neither the G-4 or R-3 ended up in production, but the design concepts of the G-4 led directly to Korolev's R-7 ICBM (essentially a cluster of G-4's or R-3A's) and the N1 superbooster. Work on the G-4 continued through 1952.

1950 January 1 - . Launch Vehicle: MKR.

- Design of 8,000 km range winged missile begun - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Program: Navaho. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spaceplane. In parallel with the R-5 Korolev OKB NII-88 begins design of 8,000 km range winged missile..

1953 January - . LV Family: R-12. Launch Vehicle: EKR.

- Expert commission examined the EKR design - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Lavochkin,

Myasishchev.

Program: Navaho.

Spacecraft Bus: Buran M.

Spacecraft: Buran M-42.

In 1951 to 1953 Korolev's design bureau had prepared an experimental trisonic ramjet design, the EKR.The expert commission ifelt that there were still many technical problems to be solved, most of which were better handled by an aircraft designer rather than Korolev. Further, Korolev had to place the highest priority on development of the R-7 ICBM. Therefore a final government decree on 20 May 1954 authorised the Lavochkin and Myasishchev aircraft design bureaux to proceed in parallel with full-scale development of trisonic intercontinental cruise missiles.

1953 April - . Launch Vehicle: Buran M, Burya La-350.

- USSR Council of Ministers approve R-7 ICBM, Buran and Burya intercontinental cruise missiles - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev, Lavochkin, Myasishchev. Program: Navaho. Informal go-ahead was given for Korolev to start design work on the R-7. In parallel, Myasishchev OKB-23 and Lavochkin OKB-301 began design of intercontinental ramjet cruise missiles..

1953 August 12 - . LV Family: R-5. Launch Vehicle: R-5M.

- Test of 400 kiloton lightweight thermonuclear warhead - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. The explosion of the RD5-6 400 kiloton warhead at Semiplatinsk proved the design of a lightweight thermonuclear warhead. Korolev began work in 1953 to develop a re-entry vehicle for this warhead..

End of 1953 - . LV Family: R-12. Launch Vehicle: Kosmos 2.

- Khrushchev and Ustinov decide to create additional independent missile design bureaux - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Khrushchev,

Korolev,

Makeyev,

Ustinov,

Yangel.

Khrushchev desired to decentralise the missile industry, since a single nuclear bomb on Moscow would wipe out Korolev's factories. Ustinov was requested to draw up a plan for two additional completely independent missile design bureaux, one in the south of the Soviet Union, the other in the Urals. It was also envisioned a third bureau would be built in the east, in Siberia, but this was never done. This effort cost tens of billions of roubles. While the managers and lead technical staff would be taken from Korolev's bureau, the working engineers, technicians, and workers for the bureau and associated factories would be recruited locally at each site. This would avoid the additional expense of building extra housing. Korolev fought to keep control, wanting to make the new bureaux just branches of his own, but Khrushchev was adamant that only completely autonomous organisations would be acceptable. Yangel was easily selected for the southern bureau, and the young Makeyev was a more contentious selection for the Ural bureau.

1954 May 20 - . Launch Vehicle: Buran M, Burya La-350.

- Soviet government decree for full-scale development of trisonic intercontinental cruise missiles. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Glushko,

Isayev,

Korolev,

Lavochkin,

Myasishchev.

Program: Navaho.

Spacecraft: Buran M-42,

Buran M-44.

Council of Soviet Ministers (SM) Decree 957-409 'On transfer of intercontinental cruise missile work to the Ministry of Aviation Industry' was issued. Korolev had to place the highest priority on development of the R-7 ICBM. Therefore the final government decree authorised the Lavochkin and Myasishchev aircraft design bureaux to proceed in parallel with full-scale development of trisonic intercontinental cruise missiles. Both missiles would use ramjet engines by Bondaryuk, astronavigation systems by R Chachikyan, inertial navigation systems by G Tolstoysov, and aerodynamics developed by TsAGI (Central Hydrodynamics Institute). Lavochkin's Burya would use rocket booster engines built by Glushko, while Myasishchev's Buran would use Isayev engines. Both missiles were to deliver a nuclear warhead over an 8,500 km range. But the warhead design specified for the Lavochkin missile had a total mass of 2,100 kg, while that for the Myasishchev missile weighed 3,500 kg.

1955 May 30 - .

- Korolev rehabilitated. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Seventeen years after his arrest, and after ten years as head of the Soviet rocketry program, Korolev's arrest and imprisonment during Stalin's purges are rescinded..

1956 During the Year - .

- Martian Piloted Complex (MPK) - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Hohmann,

Korolev.

Spacecraft Bus: TMK.

Spacecraft: MPK.

This first serious examination in the Soviet Union of manned flight to Mars was initiated by M Tikhonravov's section of Korolev's OKB-1. The Martian Piloted Complex (MPK), would be assembled in low earth orbit. Using conventional liquid propellants, it would fly a Hohmann trajectory, enter Martian orbit, and a landing craft would descend to the surface. After just over a year of surface exploration, the crew would return to earth. It was calculated that the initial mass of the MPK would be 1,630 tonnes, and a re-entry vehicle of only 15 tonnes could be returned to earth at the end of the 30 month mission. At the planned N1 payload mass of 75 to 85 tonnes, it would take 20 to 25 N1 launches to assemble the MPK.

1956 February 27 - . Launch Vehicle: R-7.

- Soviet Leadership tours Korolev's design bureau - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bulganin,

Khrushchev,

Korolev,

Ustinov.

Khrushchev, Molotov, Bulganin, and other leaders are given a tour of Korolev's OKB-1 in Kaliningrad. They are shown the R-1, R-2 and R-5 missiles as well as a mock-up of the R-7 and are awed. Ustinov reports that only five warheads would be needed to destroy Britain, and seven to nine for France. The need for the R-12 was discussed - the longer range was essential so that the missiles could be based farther from NATO's borders (the experience of the German invasion and quick destruction of forward-based units and equipment was on everyone's minds).

1956 June - . LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Vostok 8K72.

- First studies by Korolev OKB of manned spacecraft - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Feoktistov, Korolev. Program: Vostok. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Vostok. First studies by Korolev and Feoktistov of manned spacecraft. The first stage would be suborbital ballistic flights (like the US Mercury-Redstone flights) from Kapustin Yar using IRBM's. First flights not planned until 1964 - 1967..

1957 During the Year - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- USSR starts ion engine development - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Feoktistov,

Korolev.

Spacecraft Bus: TMK.

Spacecraft: TMK-E.

At the urging of S P Korolev, OKB-1 Section 12, led by M V Melnikov, started development of an ion engine. By 1959 it would be proposed that clusters of the 7.5 kgf thrust ion engine could take the TMK-E manned Mars spacecraft on a low acceleration spiralling trajectory away from the Earth until it finally reached escape velocity and headed toward Mars. But to power even such a limited engine solar panels with a total area of 36,000 square meters would be required - clearly beyond 1959 technology. Feoktistov's solution was to turn to the use of a nuclear reactor to power the ion engine.

1957 March - .

- Tikhonravov first manned and lunar spacecraft designs. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

In the spring of 1957 Korolev organised project section 9, with Tikhonravov at its chief, to design new spacecraft. By April they had completed a research plan to build a piloted spacecraft and an unmanned lunar probe, using the R-7 as the basis for the launch vehicle.

1958 May 1 - .

- Korolev OKB cancels suborbital manned flights - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Ustinov.

Program: Vostok.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Vostok.

Decision to move directly to early manned flights in orbit. Korolev, after a review with engineers, determines that planned three stage versions of the R-7 ICBM could launch a manned orbital spacecraft. Korolev advocates pursuit of manned spaceflight at the expense of the military's Zenit reconnsat program, putting him in opposition to Ustinov.

1958 June 1 - .

- Start of construction of manned spacecraft - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Myasishchev,

Tsybin.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spaceplane. Spacecraft: Vostok.

Competing manned projects. Korolev OKB-1 proposed Vostok ballistic capsule as quickest way to put a man in space while meeting Zenit project's reconnsat requirements. Under project VKA-23 (Vodushno Kosmicheskiye Apparat) Myasishchev OKB-23 proposed two designs, a faceted craft with a single tail, and a dual tail contoured version. Tsybin OKB-256 proposed seven man winged craft with variable wing dihedral. Contracts awarded to all three OKB's to proceed with construction of protoypes. R-7 booster to be used for suborbital launches.

1958 July 1 - .

- Korolev letter to Politburo - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Program: Vostok. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: Vostok. First explanation to leadership of advantages of manned spaceflight..

Summer 1958 - . Launch Vehicle: R-16.

- Khrushchev conceives of use of silos for Soviet long range missiles - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Barmin,

Khrushchev,

Korolev,

Yangel.

Khrushchev independently conceived of the idea of storing and launching ballistic missiles from subterranean silos. He called Korolev to his dacha in the Crimea. Korolev told him his idea was not feasible. He then called Barmin and Yangel. Barmin said he would study the idea. Yangel remained silent. Some time later Khrushchev's son saw a drawing of the same concept in a US aerospace magazine. He informed his father, who ordered immediate crash development of the first generation of Soviet missile silos.

1958 September 23 - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC1. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Vostok-L 8K72. FAILURE: Launcher disintegrated 93 seconds after launch due to longitudinal resonance of strap-ons.. Failed Stage: 0.

- Luna failure - booster disintegrated at T+92 seconds - . Payload: E-1 s/n 1. Mass: 361 kg (795 lb). Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Glushko, Korolev. Agency: MVS. Program: Luna. Class: Moon. Type: Lunar probe. Spacecraft: Luna E-1. This was the start of an acrimonious debated between Glushko and Korolev design bureaux over the fault and fix for the problem..

1958 November 1 - .

- Vostok spacecraft and Zenit spy satellite authorised. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Spacecraft Bus: Vostok.

Spacecraft: Vostok,

Zenit-2 satellite,

Zenit-4.

Council of Chief Designers Decree 'On course of work on the piloted spaceship' was issued. Council of Chief designers approved the Vostok manned space program, in combination with Zenit spy satellite program Korolev was authorised to proceed with development of a spacecraft to achieve manned flights at the earliest possible date. However the design would be such that the same spacecraft could be used to fulfil the military's unmanned photo reconnaissance satellite requirement. The military resisted, but Korolev won. This was formalised in a decree of 25 May 1959.

1959 February 20 - . LV Family: RT-2. Launch Vehicle: RT-1.

- RT-1 experimental solid propellant ballistic missile development authorised - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Korolev was to begin development of the three stage rocket, which was to have a range of 800 to 2500 km and a lift-off mass of 35 tonnes..

1959 May 17 - .

- PKA Spaceplane Draft Project - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Tsybin.

Spacecraft Bus: VKA.

Spacecraft: PKA.

Tsybin's design was called the gliding spacecraft (PKA). The draft project, undertaken in co-operation with Korolev's OKB-1, was signed by Tsybin on 17 May 1959.The piloted PKA would be inserted into a 300 km altitude orbit by a Vostok launch vehicle. After 24 to 27 hours of flight the spacecraft would brake from orbit, gliding through the dense layers of the earth's atmosphere. At the beginning of the descent, in the zone of most intense heating, the spacecraft would take advantage of a hull of original shape (called 'Lapotok' by Korolev after the Russian wooden shoes that it resembled). After braking to 500 to 600 m/s at an altitude of 20 km, the PKA would glide to a runway landing on deployable wings, which would move to a horizontal position from a stowed vertical position over the back of the spacecraft. Control of the PKA in flight was by rocket jets or aerodynamic surfaces, depending on the phase of flight.

1959 December 31 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Nuclear propulsion work abandoned. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Program: Lunar L3. Korolev abandons work on nuclear-powered rockets. Future launch vehicles to be based on conventional lox/keroesene propellants..

1960 January - .

- Korolev proposed an aggressive program for Communist conquest of space. - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Spacecraft: Kosmoplan. In a letter sent by Korolev to the Central Committee of the Communist Part, he pledged to provide a comprehensive plan by the third quarter of 1960 comprehensive plans for development of the new projects..

1960 January 15 - . LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Molniya 8K78.

- Molniya 8K78 design begins - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Korolev signed the order for development of a four stage rocket based on the R-7..

1960 March 3 - .

- Korolev-Khruschev meeting on space plans. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Khrushchev,

Korolev.

Spacecraft: Kosmoplan.

Korolev believed it would be truly possible with backing from the very top to have a large rocket in the USSR in a very short span of time. Unfortunately at the meeting Korolev made a slip of the tongue he would always regret, admitting that his plan had not been agreed among all of the Chief Designers. This resulted in Khrushchev throwing the matter back for a consensus plan.

1960 May 30 - .

- Korolev space development plan - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Chelomei, Korolev, Yangel. Spacecraft: Kosmoplan. Korolev revised his earlier, disapproved plan with one that now included participation of his rivals, Chelomei and Yangel..

1960 June 23 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Korolev tries to obtain support for a military orbital station - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Spacecraft: OS.

Korolev wrote to the Ministry of Defence, trying to obtain support for a military orbital station (OS). The station would have a crew of 3 to 5, orbited at 350 to 400 km altitude. The station would conduct military reconnaissance, control other spacecraft in orbit, and undertake basic space research. The N-I version of the station would have a mass of 25 to 30 tonnes and the N-II version 60 to 70 tonnes. Korolev pointed out that his design bureau had already completed a draft project, in which 14 work brigades had participated.

1960 June 23 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Soviet plan for mastery of space issued. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Chelomei,

Korolev,

Yangel.

Spacecraft Bus: TMK.

Spacecraft: TMK-E.

Decree 715-296 'On the Production of Various Launch Vehicles, Satellites, Spacecraft for the Military Space Forces in 1960-1967' authorised design of a range of spacecraft and launch vehicles by Korolev, Yangel, and Chelomei. The decree included the N1 (development of launch vehicles of up to 2,000 tonnes liftoff mass and 80 tonne payload, using conventional chemical propellants) and nuclear reactors for space power and propulsion.

1961 January 5 - . Launch Vehicle: R-16.

- State Commission Meeting - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Barmin,

Bushuyev,

Glushko,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Rudnev,

Semenov.

Program: Vostok,

Venera.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Rudnev chaired the meeting, which first heard the failure analysis for the failed Mars launches on 10 and 14 October and the R-16 catastrophe on 24 October. All of these had been accelerated to coincide with Khrushchev's visit to the United Nations in New York, in Kamanin's view a criminal rush that led to the death of 74 officers and men in the R-16 explosion. Future plans were then reviewed. Launches of probes toward Venus were planned for 20-23 January, 28-30 January, and 8-10 February. Four Vostok manned spacecraft were completed, with first launch scheduled for 5 February and the second for 15-20 February.

1961 January 20 - .

- Venera preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Spacecraft: Mars 2MV-2,

Vostok.

Korolev plans three launches between 20 January and 14 February, but clearly his teams are not ready to accomplish this. There was insufficient testing of the Object V Venera spacecraft before it was shipped from OKB-1 to the cosmodrome. OKB-1 is trying to finish Object V on site, at the same time preparing the next Vostok 3KA and an R-9 ICBM for launch. Object V is not ready, the ability of its systems to function at long ranges and periods of time on the voyage to Venus are suspect. In Kamanin's opinion, it is diverting the crews from the higher priority manned and military projects.

1961 January 31 - .

- Back at Tyuratam - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Keldysh, Korolev, Moskalenko, Semenov, Yangel. Spacecraft Bus: 2MV. Spacecraft: Mars 2MV-2. Kamanin flies to the cosmodrome with Korolev, Keldysh, Moskalenko, General Semenov, and others. Yangel's R-16 ICBM is not ready for launch yet due to continuing problems with the radio systems. The Venera is set for a 2 February launch attempt..

1961 February 4 - . 01:18 GMT - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC1. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Molniya 8K78. FAILURE: At T+531 sec, the fourth vernier chamber of Stage 3's 8D715K engine exploded because the LOX cut-off valve had not closed as scheduled and LOX flowed into the hot chamber.. Failed Stage: U.

- Sputnik 7 - .

Payload: 2MV-2 s/n 1. Mass: 6,483 kg (14,292 lb). Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Glushko,

Korolev.

Agency: RVSN.

Program: Venera.

Class: Venus.

Type: Venus probe. Spacecraft Bus: 1MV.

Spacecraft: Venera 1VA.

Decay Date: 1961-02-26 . USAF Sat Cat: 71 . COSPAR: 1961-Beta-1. Apogee: 318 km (197 mi). Perigee: 212 km (131 mi). Inclination: 64.90 deg. Period: 89.80 min.

The escape stage entered parking orbit but the main engine cut off just 0.8 s after ignition due to cavitation in the oxidiser pump and pump failure.. The payload attached together with escape stage remained in Earth orbit.

The booster launched into a beautiful clear sky, and it could be followed by the naked eye for four minutes after launch. The third stage reached earth parking orbit, but the fourth stage didn't ignite. It was at first believed a radio antenna did not deploy from the interior of the stage, and it did not receive the ignition commands. Therefore the Soviet Union has successfully orbited a record eight-tonne 'Big Zero' into orbit. The State Commission meets two hours after the launch, and argues whether to make the launch public or not, and how to announce it. Glushko proposes the following language for a public announcement: 'with the objective of developing larger spacecraft, a payload was successfully orbited which provided on the first revolution the necessary telemetry'. Korolev and the others want to minimize any statement, to prevent speculation that it was a reconnaissance satellite or a failed manned launch. Kamanin's conclusion - the rocket didn't reach Venus, but it did demonstrated a new rocket that could deliver an 8 tonne thermonuclear warhead anywhere on the planet. The commission heads back to Moscow.

1961 February 12 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Space plans - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Mikhailov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Kamanin describes Korolev. He is unable to make a decision about the man's true nature. Everyone is excited about the new seven-year plan, approved on 23 January 1960 in decree 711-296, which authorises design work to start on the N1 superbooster. In the immediate future, Vostok 3KA flights are planned every 8 to 10 days beginning 22 February until the first manned flight is achieved. The first flights will use mannequins to test the cosmonaut ejection seat. A manned flight will be attempted after two consecutive successful mannequin flights.

In the West, the failed Venera 4 launch is being analysed as an attempted manned flight. Some Italians claim to have picked up voices on radio from the satellite. Kamanin describes all of this as unfounded speculation -- the Soviet Union will not risk a man's life until two fully successful mannequin flights demonstrate safe recovery.

1961 February 12 - . 00:34 GMT - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC1. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Molniya 8K78.

- Venera 1 - .

Payload: 1VA s/n 2, Venera 1 (Sputnik 8, AMS). Mass: 644 kg (1,419 lb). Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev.

Agency: RVSN.

Program: Venera.

Class: Venus.

Type: Venus probe. Spacecraft Bus: 1MV.

Spacecraft: Venera 1VA.

USAF Sat Cat: 80 . COSPAR: 1961-Gamma-1.

Venera 1 was the first spacecraft to fly by Venus. The 6424 kg assembly was launched first into a 229 x 282 km parking orbit, then boosted toward Venus by the restartable Molniya upper stage. On 19 February, 7 days after launch, at a distance of about two million km from Earth, contact with the spacecraft was lost. On May 19 and 20, 1961, Venera 1 passed within 100,000 km of Venus and entered a heliocentric orbit. This failure resulted in only the following objectives being met: checking of methods of setting space objects on an interplanetary course; checking of extra-long-range communications with and control of the space station; more accurate calculation of the dimension of the solar system; a number of physical investigations in space. Additional Details: here....

1961 February 15 - .

- Underway to Venus - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Keldysh,

Khrushchev,

Korolev.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Venera 1VA,

Vostok.

Korolev says the Venera flight continues normally. He and Keldysh will fly to Yevpatoriya tomorrow to review long-range communications with the spacecraft. After the launch he and Keldysh talked to Khrushchev, who was very happy with the success. Meanwhile, the Vostok for the next flight attempt has arrived at Tyuratam. Launch is set for 24-25 February.

1961 February 20 - .

- Korolev space plans - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Korolev,

Vershinin.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Korolev gives a briefing to Vershinin and other military leaders at OKB-1 laying out his proposed plans for space in the next two to three years. He pushes for VVS to purchase 10 to 15 Vostok-1 or Vostok-3A spacecraft for a sustained manned flight series. The next Vostok flight is now delayed to 27-28 February. He reviews the two Vostok-1 flights to date. The first successfully orbited and recovered the dogs Strelka and Belka, the second failed to reach orbit, but the capsule successfully landed 3500 km downrange near Yakut in the Tura region, after reaching an altitude of 214 km. The dogs survived a 20-G re-entry and hard landing in the capsule.

1961 March - . Launch Vehicle: RS.

- RS project cancelled - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Chelomei, Korolev, Tsybin. Tsybin's design bureau had been taken over by Chelomei, and work on the RS was stopped in the spring of 1961, with three airframes nearly finished. Tsybin went to work for Korolev at OKB-1..

1961 March 2 - .

- Vostok launch preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Alekseyev, Semyon,

Bushuyev,

Feoktistov,

Gallay,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Voskresenskiy,

Yazdovskiy.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Korolev, Yazdovskiy, Gallay, Feoktistov, Makarov, and Alekseyev spend over three hours editing the 'Instructions to Cosmonauts'. This is the first flight manual in the world for a piloted spacecraft, including instructions for all phases of flight and emergency situations. Korolev, Keldysh, Bushuyev, and Voskresenskiy want the instructions to be simply 'put on suit, check communications, observe functioning of the spacecraft'. Korolev is motivated by his belief that on this single-orbit flight everything should occur automatically. Kamanin, Yazdovskiy, Gallay, and Smirnov are categorically against such a passive role for the cosmonaut. They argue that the cosmonauts know the equipment and must be capable of manually flying the spacecraft after releasing the electronic logical lock. They need to observe the instruments, report on their status by radio, and make journal entries. The emotions of the cosmonaut during high-G's and zero-G must be understood in order to fully prepare the cosmonauts that will follow. After long debate, Korolev and Keldysh give in. The agreed first edition of the flight manual is signed by Korolev and Kamanin. The next Vostok 3KA launch is set for 9 March.

1961 March 4 - .

- Vostok flight preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Alekseyev, Semyon,

Korolev,

Yazdovskiy.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Korolev, Alekseyev, Yazdovskiy, and other engineers lay out the plan for the preparation of the cosmonaut on launch day. The cosmonaut will be put in Nedelin's cottage at Baikonur Area 2 the night before the launch, be awakened five hours before launch, and undergo a physical examination. Kamanin and Korolev will be in the bunker at the launch pad for at least the next two launches. After the launch, Kamanin is to fly to the recovery zone to be present for the landing of the spacecraft.

1961 March 7 - . LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Vostok 8K72K.

- R-7 Failure Commission - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bogomolov,

Glushko,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Kosberg,

Sokolov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Keldysh, Korolev, Sokolov, Glushko, Bogomolov hear testimony from Kosberg on the causes of the RO-7 engine failure on the 22 December 1960 launch, that resulted in the suborbital flight of the Vostok capsule with a landing in Tura. The causes are not completely understood, but the bottom line is that a fuel line must have leaked. Further testimony is offered on the booster trajectory, landing time at various points along the trajectory, tracking station readiness, communications lessons, and recovery efforts. The communications are clearly unreliable. The radius of the HF radio is 5000 km, and 1500 km for UHF. TsP Moscow and PU Tyuratam, plus Novosibirsk, Kolpachev, Khabarovsk, and Yelizov (Kamchatka) all have HF and UHF transceivers. But due to practical reception problems, only UHF communications were available at Tyuratam, Kolpachev, and Yelizov, and only HF at Novosibirsk and Khabarovsk. It is recommended that each IP tracking station should have a Chief Communications Officer, a cosmonaut to act as capsule communicator, a physician, and a representative from the Ministry of Communications to assure action on problems.

1961 March 17 - .

- Tyuratam - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Nelyubov,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Titov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

The cosmonauts play chess and cards on the flight to Tyuratam. At the airfield, Korolev, Keldysh, and five film cameramen await the cosmonauts. Korolev and Keldysh warmly greet the cosmonauts, but categorically refuse to be filmed. Korolev asks each cosmonaut one or two technical questions. All are correctly answered. Korolev says he wants to ensure that each one of them is 'ready to fly today'. As of now, six Vostoks have been launched, of which four reached orbit, and two landed successfully (one of these albeit after an emergency separation from the third stage on a suborbital trajectory). Two have been unsuccessful, including one on-pad failure on 28 July 1960. Two hours after arrival the cosmonauts go to the MIK assembly hall to familiarise themselves with the launch vehicle and spacecraft. At 14:00 Kamanin meets with the cosmonauts to review the 'Cosmonaut's Manual'. They make several suggestions. They do not feel it is necessary to loosen the parachute harness during the one-orbit flight. They note that the gloves are tried on only 15 minutes before the launch, and not on the closing of the hatch as indicated by Alekseyev. They recommend that a shortened version of the manual should be on board the spacecraft for use in case of a manual re-entry. Communications will be mainly using the laryngeal microphone Incidents will be recorded in the ship's log. The cosmonauts should be able to manually activate the reserve parachute. Kamanin agrees with the latter, but there is no time to change it for the first flight.

1961 March 22 - . LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Vostok 8K72K.

- Flight preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Barmin,

Gagarin,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Nelyubov,

Titov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Between 10:00 and 12:00 Chief Designer of Launch Facilities Barmin meets with the cosmonauts. He reviews the launch mechanism. The rocket is suspended at the 'shoulders' of the strap-ons, on four swivelled supports. After the rocket has lifted 49 mm, it is free from these, and counterweights weighing dozens of tonnes will swing them back and away from the rising booster. At 12:00 Kamanin meets with Keldysh and Korolev. They agree with his position that the flight be announced as soon as the cosmonaut is safely in orbit.

1961 March 25 - . 05:54 GMT - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC1. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Vostok 8K72K.

- Korabl-Sputnik 5 - .

Payload: Vostok 3KA s/n 2. Mass: 4,695 kg (10,350 lb). Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Goreglyad,

Kamanin,

Karpov,

Keldysh,

Kirillov,

Korolev,

Nelyubov,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Titov,

Voskresenskiy,

Yazdovskiy.

Agency: RVSN.

Program: Vostok.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Duration: 0.0600 days. Decay Date: 1961-03-25 . USAF Sat Cat: 95 . COSPAR: 1961-Iota-1. Apogee: 175 km (108 mi). Perigee: 175 km (108 mi). Inclination: 64.90 deg. Period: 88.00 min.

Carried dog Zvezdochka and mannequin Ivan Ivanovich. Ivanovich was again ejected from the capsule and recovered by parachute, and Zvezdochka was successfully recovered with the capsule on March 25, 1961 7:40 GMT.

Officially: Development of the design of the space ship satellite and of the systems on board, designed to ensure man's life functions during flight in outer space and return to Earth. Additional Details: here....

1961 March 27 - .

- Vostok cleared for manned flight - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Dementiev,

Korolev,

Kozlov,

Moskalenko,

Ustinov,

Voronin.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

The capsule was recovered 45 km southeast of Votinsk. The mannequin was ejected successfully from the aircraft, the dog Zvezdochka was fine, and was displayed to journalists all day. Therefore all is ready for a manned flight. The cosmonauts agree: 'Everything is finished, we can fly'. All is ready for a one-orbit flight with recovery in the USSR, but Kamanin still worries about the lack of any realistic plan in emergency situations. The environmental control system has still not completed endurance tests, and won't be able to keep the cosmonaut alive for the ten to twelve days it would take the spacecraft to decay from orbit if the retrorocket fails. Trials with the hot mock-up of the ECS in the capsule have still not been successful. Furthermore, a recovery at sea is not practical.

The pace quickens leading to the first human spaceflight. Kamanin coordinates matters with Korolev and Voronin, and then discusses the ECS problems and cosmonaut landing issues with Dementiev. Plans are made for a meeting with Ustinov and Kozlov. In the evening a meeting of the General Staff is held. Decisions made: 1) Announce the name of the cosmonaut as soon as he is in orbit; 2) improve VVS support (aircraft, helicopters) needed to pick up the cosmonaut immediately after landing; 3) issue a formal letter to Moskalenko on rules for filming of the cosmonaut at the launch site; 4) organise an examination of the 11 cosmonauts not in the group of six now being prepared for flights.

1961 March 28 - .

- Vostok problems review - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Dementiev,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Voronin.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

The meeting is held at G T Voronin's OKB-124 at the 'Daks' factory. All of the program bigwigs are there (Korolev, Keldysh, etc). The big issue is the problem with the oxygen regenerator. On the 10 day trial 4 litres of lithium chloride were consumed, but the test was unsuccessful. A new solution of chlorine-lithium is proposed. But this is dangerous - the doctors are worried that if it gets into the cosmonauts body, it will poison him. A sharp discussion ensues, but the final decision is to try a five day trial with lithium chloride. At 12:00 the commission proceeds to Dementiev's GKAT. The tests of the Vostok recovery system are reviewed. There were to have been two to four ejection seat tests from Il-28 bombers, tests, plus tests at sea at Fedosiya of the NAZ ejection seat and the characteristics of the parachute underwater. The discussion turns again to the five-day ECS cabin test. It is decided to keep the faulty gas analyser, but not to connect it to the telemetry - the readings will be read with a television camera instead. There is a clear political aspect in the argument between the VVS design bureau and the institute over the performance of the ECS system. Lieutenant-General Kolkov orders yet another examination of the cosmonauts.

1961 March 31 - .

- Vostok preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Grechko, Andrei,

Korolev,

Malinovskiy,

Vershinin,

Voronin,

Zakharov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

The VVS leadership has been diverted for the last three days in meetings of the General Staff of the Warsaw Pact. At 09:00 Kamanin takes a break to prepare two letters. One goes to the Ministry of Defence, certifying readiness for the launch of Vostok 1 on 10-20 April; the other goes to Zakharov on the General Staff, turning over all in-flight photographs to the VVS. Vershsinin pages through Kamanin's photo album of earth photographs taken during the unmanned Vostok test flights. They show the precise orbital orientation of the spacecraft. He says he will show these to Grechko and Malinovskiy, trying to convince them of the usefulness of manned spaceflight. Kamain calls Korolev and advises him that Voronin is ready. Korolev says that he plans to put wood wool into the cabin to absorb any excess lithium chloride.

1961 April 4 - .

- VVS General Staff certifies flight readiness of cosmonauts Gagarin, Titov, and Nelyubov. - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Filatyev,

Gagarin,

Khrushchev,

Korolev,

Moskalenko,

Nelyubov,

Rafikov,

Titov,

Zaikin.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

They also, on the basis of the recent examinations and interviews, clear the rest of the cosmonaut trainees for flight except for Rafikov, Filatev, and Zaikin, who passed the examinations but had not yet completed all the tests and training. Moskalenko has given approval for a Soviet film team to go to Tyuratam and film preparations for the flight. At the Presidium meeting Khrushchev had questioned what would be done if the cosmonaut reacted poorly in the first minute of the flight. Korolev answered in his deep voice: 'Cosmonaut are extraordinarily trained, they know the spacecraft and flight conditions better than I and we are confident of their strength'. The flight is still seen as very risky - of seven Vostoks flown unmanned so far, five made it to orbit, three landed safely, but one did not. On the other hand, both recent Venera launch attempts reached low earth orbit.

1961 April 5 - .

- Tyuratam - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gagarin,

Gallay,

Goreglyad,

Korolev,

Nelyubov,

Titov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Kamanin departs for the airport in the morning after a good breakfast. There was a fresh snowfall overnight, and Moscow looks beautiful. Three Il-14's wait to shuttle the six cosmonauts and other VVS staff to the launch centre. Gagarin and Nelyubov will fly in Kamanin's aircraft, and Titov and the others in General Goreglyad's. The third aircraft will carry the physicians and film team. The aircraft depart at fifteen-minute intervals, and the entire flight is in beautiful weather. Kamanin's Il-14 lands at Tyuratam at 14:30. Korolev, Gallay, and officers of the staff of the cosmodrome are there to greet them. Korolev requests additional last-minute training for the cosmonauts in manual landing of the spacecraft, suit donning, and communications, but Kamanin refuses. He sees no reason for any training not already agreed in the official plan. Korolev says rollout of the booster is planned for 8 April, followed by launch on 10 or 11 April. Everyone wants to know first - Gagarin or Titov? But Kamanin has not made a final decision yet. Gagarin shows hesitancy in accepting the automatic parachute deployment on the first flight, and only reluctantly agrees to the compromise solution. Titov is a stronger character, better able to hold up during a long duration mission, such as the one-day flight planned for the second mission. But the first into space will be the object of all of the attention from the news media and public. There is not a day that goes by that Kamanin does not think through the issue, without reaching a final conclusion. In the evening the cosmonauts go to the theatre, but the projectionist refuses to run the planned movie on orders of the base commander.

1961 April 6 - .

- Vostok 1 State Commission - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Alekseyev, Semyon,

Gagarin,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Rudnev,

Titov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Rudnev arrives at the cosmondrome, and the first state commission meeting is held with Korolev and the technicians at 11:30. The oxygen regenerator is still not ready, and it is decided to fly with the old dehumidifier on the first flight, since only a 90 minute mission is planned anyway. The suit and all recovery systems worked perfectly on the 9 and 25 March mannequin flights, so the NAZ system is deemed ready for flight. After the meeting Rudnev and Makarov of the KGB go to work on the written orders that will be binding on the cosmonauts in case of accidental landing on foreign territory. Kamanin, Keldysh, and Korolev draw up the final draft of the announcements to be issued in case of normal orbital insertion and after successful landing. In the evening Gagarin and Titov try on their individual suits and Alekseyev checks the parachute systems. The cosmonauts return to the hotel at 11 pm.

1961 April 8 - .

- Vostok 1 State Commission - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Gagarin,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Moskalenko,

Titov,

Yazdovskiy.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Rudnev chairs the meeting, in which Kamanin recommends that Gagarin pilot the first manned spaceflight, with Titov as backup. A discussion follows on whether to have a representative from the FAI at the launch in order to obtain registration of the world record. Marshal Moskalenko and Keldysh are opposed - they don't want anyone from outside at the secret cosmodrome. It is decided to enclose the code to unlock the controls of the spacecraft in a special packet. Gagarin will have to break it open in order to get the code that will allow him to override the automatic system and orient the spacecraft manually for re-entry. An emergency ejection during ascent to orbit is discussed. It is decided that only Korolev or Kamanin will be allowed to manually command an ejection in the first 40 seconds of flight. After that, the process will be automatic. There is embarrassment when Moskalenko confronts Yazdovskiy: 'so why are you here, when you're a veterinarian and only handle dogs?' Kamanin has to explain that Yazdovskiy is actually a medical doctor. After the meeting, Kamanin reviews Titov's training in the spacecraft, which has gone well.

1961 April 10 - .

- Vostok preparations - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bykovsky,

Gagarin,

Korolev,

Moskalenko,

Nelyubov,

Nikolayev,

Popovich,

Rudnev,

Titov.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft Bus: Soyuz.

Spacecraft: Sever.

Kamanin plays badminton with Gagarin, Titov, and Nelyubov, winning 16 to 5. At 12:00 a meeting is held with the cosmonauts at the Syr Darya River. Rudnev, Moskalenko, and Korolev informally discuss plans with Gagarin, Titov, Nelyubov, Popovich, Nikolayev, and Bykovsky. Korolev addresses the group, saying that it is only four years since the Soviet Union put the first satellite into orbit, and here they are about to put a man into space. The six cosmonauts here are all ready and qualified for the first flight. Although Gagarin has been selected for this flight, the others will follow soon - in this year production of ten Vostok spacecraft will be completed, and in future years it will be replaced by the two or three-place Sever spacecraft. The place of these cosmonauts here does not indicate the completion of our work, says Korolev, but rather the beginning of a long line of Soviet spacecraft. Korolev predicts that the flight will be completed safely, and he wishes Yuri Alekseyevich success. Kamanin and Moskalenko follow with their speeches. In the evening the final State Commission meeting is held. Launch is set for 12 April and the selection of Gagarin for the flight is ratified. The proceedings are recorded for posterity on film and tape.

1961 April 11 - .

- Vostok 1 countdown - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Feoktistov,

Gagarin,

Korolev,

Titov,

Yazdovskiy.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

The booster is rolled out to the pad at 05:00. At 10:00 the cosmonauts meet with Feoktistov for a last review of the flight plan. Launch is set of 09:07 the next day, followed by shutdown and jettison of the lateral boosters of the first stage at 09:09, and orbital insertion at 09:18. The spacecraft will orient itself toward the sun for retrofire at 09:50. At 10:15 the first command sequence will be uploaded to the spacecraft, followed by the second at 10:18 and the third at 10:25. Retrofire of the TDU engine will commence at 10:25:47. The service module will separate from the capsule at 10:36 as the capsule begins re-entry. The capsule's parachute will deploy at 10:43:43 and at 10:44:12 the cosmonaut's ejection seat will fire. While the cosmonauts go through this, the booster has been brought upright on the pad, the service towers raised, and all umbilical connections made. Korolev, Yazdovskiy, and the others make a final inspection at the pad prior to the commencement of the countdown. At 13:00 Gagarin meets a group of soldiers, NCO's, and officers. After this Kamanin and the cosmonauts go to the cottage formerly occupied by Marshal Nedelin, where they will spend the last night before launch. They eat 'space food' out of 160 g toothpaste-type tubes for lunch - two servings of meat puree and one of chocolate sauce. Gagarin's blood pressure is measured as 115/60, pulse 64, body temperature 36.8 deg C. He then subjects to placement of the biosensors he will wear during the flight, and baseline measurements are taken for an hour and twenty minutes. He is very calm through all this. At 21:30 Korolev comes to the cottage, says good night to the cosmonauts, then goes back out to check on launch preparations. Gagarin and Titov go to bed after this. Kamanin stays up a while in the next room, listening to them talk to one another in the dark.

1961 April 12 - . 06:07 GMT - . Launch Site: Baikonur. Launch Complex: Baikonur LC1. LV Family: R-7. Launch Vehicle: Vostok 8K72K.

- Vostok 1 - .

Call Sign: Kedr (Cedar ). Crew: Gagarin.

Backup Crew: Nelyubov,

Titov.

Payload: Vostok 3KA s/n 3. Mass: 4,725 kg (10,416 lb). Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Karpov,

Keldysh,

Korolev,

Moskalenko,

Rudnev.

Agency: RVSN.

Program: Vostok.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Flight: Vostok 1.

Spacecraft: Vostok.

Duration: 0.0750 days. Decay Date: 1961-04-12 . USAF Sat Cat: 103 . COSPAR: 1961-Mu-1. Apogee: 315 km (195 mi). Perigee: 169 km (105 mi). Inclination: 65.00 deg. Period: 89.30 min.

First manned spaceflight, one orbit of the earth. Three press releases were prepared, one for success, two for failures. It was only known ten minutes after burnout, 25 minutes after launch, if a stable orbit had been achieved.

The payload included life-support equipment and radio and television to relay information on the condition of the pilot. The flight was automated; Gagarin's controls were locked to prevent him from taking control of the ship. The combination to unlock the controls was available in a sealed envelope in case it became necessary to take control in an emergency. After retrofire, the service module remained attached to the Sharik reentry sphere by a wire bundle. The joined craft went through wild gyrations at the beginning of re-entry, before the wires burned through. The Sharik, as it was designed to do, then naturally reached aerodynamic equilibrium with the heat shield positioned correctly.

Gagarin ejected after re-entry and descended under his own parachute, as was planned. However for many years the Soviet Union denied this, because the flight would not have been recognized for various FAI world records unless the pilot had accompanied his craft to a landing. Recovered April 12, 1961 8:05 GMT. Landed Southwest of Engels Smelovka, Saratov. Additional Details: here....

1961 April 15 - .

- Gagarin in Moscow - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Gagarin, Korolev. Program: Vostok. Flight: Vostok 1. Gagarin first meets with Korolev, then holds a press conference. At 15:30 he meets with the VVS Military Soviet..

1961 May 3 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- The draft project of the TKS Heavy Space Station was completed - . Nation: Russia. Related Persons: Korolev. Spacecraft Bus: OS. Spacecraft: TKS Heavy Space Station. Also known as TOSZ - Heavy Orbital Station of the Earth, this was Korolev's first 1961 project for a large N1-launched military space station..

1961 May 20 - .

- Vostok 2 discussions - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Bushuyev,

Feoktistov,

Korolev,

Yazdovskiy.

Program: Vostok.

Flight: Vostok 2.

Spacecraft: Sever,

Vostok.

Kamanin, Yazdovskiy, Bushuyev, and Feoktistov fly to Sochi. Korolev arrives on the next flight, and discussions begin on plans for the second Soviet manned spaceflight. Korolev wants a one-day/16-orbit flight, but Kamanin thinks this is too daring and wants a 3 to 4 orbit flight. Korolev rejects this, saying recovery on orbits 2 to 7 is not possible since the solar orientation sensor would not function (retrofire would have to take place in the earth's shadow). But Kamanin believes one day is too big a leap since the effects of sustained zero-G are not known. He finally agrees to a one-day flight, but with the proviso that a manually-oriented retrofire can be an option on orbits 2 to 7 if the cosmonaut is feeling unwell. Korolev reports that the new Sever spacecraft should be ready for flight by the third quarter of 1962. OKB-1 is working hard on the finding solutions to the problems of manoeuvring, rendezvous, and docking in orbit. Kamanin tells Korolev that it would be difficult to recruit and train three-man crews in time to support such an aggressive schedule.

1961 June 1 - . Launch Vehicle: N1.

- Moon program go-ahead in response to U.S. start - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Chelomei,

Korolev,

Yangel.

Program: Lunar L1.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Spacecraft: LK-1,

Soyuz A,

Soyuz B,