Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Mercury MA-7

Atlas D Mercury Credit: NASA |

AKA: Aurora 7. Launched: 1962-05-24. Returned: 1962-05-24. Number crew: 1 . Duration: 0.21 days. Location: Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, IL.

Scott Carpenter in Aurora 7 is enthralled by his environment but uses too much orientation fuel. Yaw error and late retrofire caused the landing impact point to be over 300 km beyond the intended area and beyond radio range of the recovery forces. Landing occurred 4 hours and 56 minutes after liftoff. Astronaut Carpenter was later picked up safely by a helicopter after a long wait in the ocean and fears for his safety. NASA was not impressed and Carpenter left the agency soon thereafter to become an aquanaut.

Official NASA Account of the Mission from This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury, by Loyd S. Swenson Jr., James M. Grimwood, and Charles C. Alexander, NASA Historical Series SP-4201, 1966.

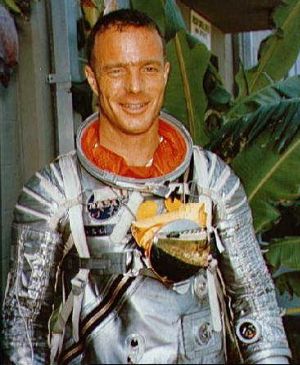

At 1:15 a.m., May 24, 1962, Scott Carpenter was awakened in his quarters in Hangar S at Cape Canaveral. He ate a breakfast of filet mignon, poached eggs, strained orange juice, toast, and coffee, prepared by his dietitian. During the next hour, starting about 2:15 a.m., he had a physical examination and stood patiently in his underwear as the sensors were attached at various spots on his lean body, and by 3:25 he had donned his silver suit and had it checked. Everything had gone so smoothly that Carpenter had time to relax in a contour chair while waiting to board the van.

At 3:45, Carpenter and his retinue, including Joe Schmitt and John Glenn, marched from the hangar and climbed aboard the vehicle for a slow ride to Pad 14, where Aurora 7 sat atop the Atlas. Again there was a pause, during which a Weather Bureau representative presented a briefing to the astronaut-of-the-day, predicting a dispersal of the ground fog then hovering around the launch site. Finally, at 4:35, Carpenter received word from Mercury Control to ascend the gantry. Just before he boarded the elevator he stopped to swap greetings with and to thank the flight support crewmen. After the final checks in the gantry white room, the astronaut crawled into the capsule and got settled with only minor difficulties, and soon the capsule crew was bolting the hatch. This time all 70 bolts were aligned properly.

Meanwhile the booster countdown was racing along. Christopher Kraft recalled that the countdown was "as near perfect as could be hoped for." The only thing complicating the prelaunch sequence was the persistent ground fog and broken cloudiness at dawn. Strapped in the contour couch, and finding the new couch liner comfortable, Carpenter was busy verifying his preflight checklist. Just 11 minutes before the scheduled launch time, the operations team decided that adequate camera coverage was not yet possible, and three consecutive 15-minute holds were called. Although Carpenter felt that he could continue in a hold status indefinitely, he was thirsty and drank some cold tea from his squeeze bottle supply. During the holds he talked with his wife Rene and their four children at the Cape, assuring them that all was well.

The rising sun rapidly dispelled the ground fog. Then at 7:45 a.m., after the smoothest countdown of an American manned space mission to date, Mercury-Atlas 7, bearing Aurora 7, rose majestically off the pad while some 40 million people watched by television.

Kraft, the flight director, described the powered phase of the flight as so "excellent" that the decision to "go-for-mission" was almost routine. Seventy-three seconds from launch, the booster's radio inertial guidance system locked on and directed the flight from staging until T plus 5:38 minutes. Actually this amounted to some 28 seconds after the Atlas sustainer engine had died, but no guidance inputs were possible after engine shutdown. Carpenter tried using the parabolic mirror on his chest to watch the booster's programming, but he could see only a reflection of the pitch attitude. At about 35,000 feet he noticed out his window a contrail, and then an airplane producing another contrail. The sky began to darken; it was not yet black, but it was no longer a light blue.

The booster performed much more quietly than Carpenter had expected from all its awesome power. Vibration had been slight at liftoff. Booster engine cutoff was smooth and gentle, but a few seconds later the noise accompanying maximum aerodynamic stress began to build up. A wisp of smoke that appeared out the window gave Carpenter the impression that the escape tower had jettisoned, but a glance showed that it was still there. Shortly thereafter, when the tower did separate from the capsule, Carpenter "felt a bigger jolt than at staging." He watched the tower cartwheel lazily toward the horizon, smoke trailing from its three rocket nozzles.

Sustainer engine cutoff came only as a gentle drop in acceleration. Two bangs were cues that the clamp-ring explosive bolts had fired and that the posigrade rockets had propelled the spacecraft clear of the booster. Now Aurora 7 was on its own and in space. Becoming immediately aware that he was weightless, Carpenter elatedly reported that zero g was pleasant. Just as the capsule and booster separated, the astronaut had noticed that the capillary tube in his liquid-test apparatus seemed to fill. Then he averted his gaze; it was time to turn the spacecraft around to its normal backward flying orbital attitude. Since Glenn had left this maneuver to the automatic control system and the cost in fuel had been high, Carpenter used fly-by-wire. The spacecraft came smartly around at an expense of only 1.6 pounds of fuel, compared with over 5 pounds used on Glenn's MA-6 maneuver.

As the capsule swung around from antenna-canister-forward to heatshield-forward, Carpenter was impressed by the fact that he felt absolutely no angular motion; his instruments provided the only evidence that the turnaround maneuver was being executed. Like Glenn, he was amazed that he felt no sensation of speed, although he knew he was traveling at orbital velocity (actually 17,549 miles per hour). Soon he had his first awe-inspiring view of the horizon - "an arresting sight," as he described it. Quickly checking his control systems, he found everything in order. Unknown to him, however, the horizon scanner optically sensing his spacecraft's pitch attitude was off by about 20 degrees. It was some time before he deduced this system was in error.

As Glenn had done, Carpenter peered out the window to track the spent Atlas sustainer engine. The tankage appeared to fall downward, as the engineers had predicted, and was tumbling away slowly. A trail of ice crystals two or three times longer than the launch vehicle streamed from its nozzle. Over the Canary Islands, Carpenter still could see the sustainer tagging along below the spacecraft. Meanwhile the astronaut continued to check the capsule systems and report his findings to the tracking sites. Over Kano, in mid-Nigeria, he said that he was getting behind in his flight plan because of difficulty in loading his camera with the special film to photograph the Earth-horizon limb. Before he moved beyond radio range of Kano, however, he managed to snap a few photographs. Although it was now almost dusk on his first "45-minute day," Carpenter was becoming increasingly warm and began adjusting his suit-temperature knob.

Over the Indian Ocean on his first pass, Carpenter glanced down for a view through the periscope, which he found to be quite ineffective on the dark side of Earth. Concluding that the periscope seemed to be useless at night, he returned to the window for visual references. Even when the gyros were caged and he was not exactly sure of his attitude position, he felt absolutely no sensation of disorientation; it was a simple matter in the daylight to roll the spacecraft over and watch for a landmark to pop into view. Carpenter mentioned many recognizable landmarks, such as Lake Chad, Africa, the rain forests of that continent, and Madagascar. But he was a little surprised to find out that most of Earth when seen from orbit is covered by clouds the greater part of the time.

While over the Indian Ocean, Carpenter discovered that his celestial observations were hampered by glare from light seepage around the satellite clock inside the capsule. The light from the rim of the clock, which should presumably have been screened, made it hard for him to adjust his eyes to night vision. To Slayton at the Muchea station, Carpenter reported that he could see no more stars from his vantage point in space than he could have seen on Earth. Also he said that the stars were not particularly useful in gaining heading information.

Like his orbital predecessor, Carpenter failed to see the star- shell flares fired in an observation experiment. This time the flares shot up from the Great Victoria Desert near Woomera, Australia, rather than from the Indian Ocean ship. According to the plan, four flares of one-million candlepower were to be launched for Carpenter's benefit on his first orbit, and three more each on his second and third passes. On the first try the flares, each having a burning time of 1½ minutes, were ignited at 60-second intervals. At this time most of the Woomera area was covered by clouds that hid the illumination of the flares; the astronaut consequently saw nothing and the experiment was discontinued on the succeeding two passes, as weather conditions did not improve.

Out over the Pacific on its first circuit, Aurora 7 performed nicely. The Canton Island station received the telemetered body temperature reading of 102 degrees and asked Carpenter if he was uncomfortable at that temperature. "No, I don't believe that's correct," Carpenter replied. "I can't imagine I'm that hot. I'm quite comfortable, but sweating some." The medical monitors accepted Carpenter's self-assessment and concluded that the feverish temperature reading resulted from an error in the equipment. For the rest of the journey, however, the elevated temperatures persisted, causing the various communicators to ask frequently about Carpenter's physical status.

The food Carpenter carried on his voyage was different from Glenn's which was of the squeeze-tube, baby-food variety. For Carpenter the Pillsbury Company had prepared three kinds of snacks, composed of chocolate, figs, and dates with high-protein cereals; and the Nestlé Company had provided some "bonbons," composed of orange peel with almonds, high-protein cereals with almonds, and cereals with raisins. These foods were processed into particles about three-fourths of an inch square. Coated with an edible glaze, each piece was packaged separately and stored in an opaque plastic bag. As he passed over Canton he reported that he had eaten one bite of the inflight food, which was crumbling badly. Weightless crumbs drifting around in the cabin were not only bothersome but also potentially dangerous to his breathing. Though he had been able to eat one piece, his gloved hands made it awkward to get the food to his mouth around the helmet microphones. Once in his mouth, however, the food was tasty enough and easy enough to eat.

During the second orbit, as he had on the first, Carpenter made frequent capsule maneuvers with the fly-by-wire and manual-proportional modes of attitude control. He slewed his ship around to make photographs; he pitched the capsule down 80 degrees in case the ground flares were fired over Woomera; he yawed around to observe and photograph the airglow phenomenon; and he rolled the capsule until Earth was "up" for the inverted flight experiment. Carpenter even stood the capsule on its antenna canister and found that the view was exhilarating. Although the manual control system worked well, the MA-7 pilot had some difficulty caging the attitude gyros to zero before inverting the spacecraft. On two occasions he had to recycle the caging operation after the gyros tumbled beyond their responsive limits.

Working under his crowded experiment schedule and the heavy manual maneuver program, on six occasions Carpenter accidentally actuated the sensitive-to-the-touch, high-thrust attitude control jets, which brought about "double authority control," or the redundant operation of both the automatic and the manual systems. So by the end of the first two orbits Carpenter's control fuel supply had dipped to about 42 percent in the manual tanks and 45 percent in the automatic tanks. During his second orbit, ground capsule communicators at various tracking sites repeatedly reminded him to conserve his fuel.

Although his fuel usage was high during the second circumnavigation, Carpenter still managed to continue the experiments. Just as he passed over the Cape, for example, an hour and 38 minutes from launch, Carpenter deployed the multicolored balloon. For a few seconds he saw the confetti spray, signaling deployment. Then, as the line lazily played out, he realized that the balloon had not inflated properly; only two of the five colors - orange and dull aluminum - were visible, the orange clearly the more brilliant. Two small, earlike appendages about six to eight inches each, described as "sausages," emerged on the sides of the partially inflated sphere. The movement of the half-inflated balloon was erratic and unpredictable, but Carpenter managed to obtain a few drag resistance measurements. A little more than a half hour after the balloon was launched, Carpenter began some spacecraft maneuvers and the tether line twined to some extent about the capsule's antenna canister. Carpenter wanted to get rid of the balloon and attempted to release it going into the third orbit over the Cape, but the partially successful experimental device stayed doggedly near the spacecraft.

As Carpenter entered the last orbit, both his automatic and manual control fuel tanks were less than half full. So Aurora 7 began a long period of drifting flight. Short recess periods to conserve fuel had occurred earlier in the flight, but now Carpenter and his ship were to drift in orbit almost around the world. Although his rapidly depleting fuel supply had made the drift a necessity, this vehicle control relaxation maneuver, if successful, would be a valuable engineering experiment. The results would be most useful in planning the rest and sleep periods for an astronaut on a longer Mercury mission. Carpenter enjoyed his floating orbit, observing that it was a simple matter to start a roll rate of perhaps one degree per second and let the capsule slowly revolve as long as desired. Aurora 7 drifted gracefully through space for more than an hour, or almost until retrofire time.

While in his drifting flight, Carpenter used the Moon to check his capsule's attitude. John Glenn had reported some difficulty in obtaining and holding an absolute zero-degree heading. Carpenter, noting that the Moon appeared almost in the center of his window, oriented the spacecraft so that it held the Moon on the exact center mark and maintained the position with ease.

During the third orbital pass, Carpenter caught on film the phenomenon of the flattened Sun at sunset. John O'Keefe and his fellow scientists at Goddard had taught Carpenter that the color layers at sunset might provide information on light transfusion characteristics of the upper atmosphere. Carpenter furnished a vivid description of the sunset to the capsule communicator on the Indian Ocean ship:

The sunsets are most spectacular. The earth is black after the sun has set. . . . The first band close to the earth is red, the next is yellow, the next is blue, the next is green, and the next is sort of a - sort of a purple. It's almost like a very brilliant rainbow. These layers extend from at least 90 degrees either side of the sun at sunset. This bright horizon band extended at least 90 degrees north and south of the position at sunset.He took some 19 pictures of the flattened Sun.

As Carpenter drifted over oceans and land masses, he observed and reported on the haze layer, or airglow phenomenon, about which Glenn had marveled. Carpenter's brief moments of airglow study during the second orbit failed to match the expectations he had derived from Glenn's reports and the Goddard scientists' predictions on the phenomenon. Having more leisure on his third circuit, Carpenter described the airglow layer in detail to Slayton at the Muchea tracking site:

. . . the haze layer is very bright. I would say about 8 to 10 degrees above the real horizon. And I would say that the haze layer is about twice as high above the horizon as the bright blue band at sunset is; it's twice as thick. A star - stars are occluded as we pass through this haze layer. I have a good set of stars to watch going through at this time. I'll try to get some photometer readings. . . . It is not twice as thick. It's thinner, but it is located at a distance about twice as far away as the top of the band at sunset. It's very narrow, and as bright as the horizon of the earth itself.The single star, not stars, that Carpenter tracked was Phecda Ursae Majoris, in the Big Dipper or Great Bear constellation, with a magnitude of 2.5.

With each sunrise, Carpenter also saw the "fireflies," or "Glenn effect," as the Russians were calling it. To him the particles looked more like snowflakes than fireflies, and they did not seem to be truly luminous, as Glenn had said. The particles varied in size, brightness, and color. Some were gray, some were white, and one in particular, said Carpenter, looked like a helical shaving from a lathe. Although they seemed to travel at different speeds, they did not move out and away from the spacecraft as the confetti had in the balloon experiment.

At dawn on the third pass Carpenter reached for a device known as a densitometer, that measured light intensity. Accidentally his gloved hand bumped against the capsule hatch, and suddenly a cloud of particles flew past the window. He yawed right to investigate, noting that the particles traveled across the front of the window from right to left. Another tap of the hand on the hatch sent off a second shower; a tap on the wall produced another. Since the exterior of the spacecraft evidently was covered with frost, Glenn's "fireflies" became Carpenter's "frostflies."

Until Aurora 7 reached the communication range of the Hawaiian station on the third pass, Christopher Kraft, directing the flight from the Florida control center, considered this mission the most successful to date; everything had gone perfectly except for some overexpenditure of hydrogen peroxide fuel. Carpenter had exercised his manual controls with ease in a number of spacecraft maneuvers and had made numerous and valuable observations in the interest of space science. Even though the control fuel usage had been excessive in the first two orbits, by the time he drifted near Hawaii on the third pass Carpenter had successfully maintained more than 40 percent of his fuel in both the automatic and the manual tanks. According to the mission rules, this ought to be quite enough hydrogen peroxide, reckoned Kraft, to thrust the capsule into the retrofire attitude, hold it, and then to reenter the atmosphere using either the automatic or the manual control system.

The tracking site at Hawaii instructed Carpenter to start his preretrofire countdown and to shift from manual control to the automatic stabilization and control system. He explained to the ground station over which he was passing at five miles per second that he had gotten somewhat behind on the preretro checkoff list while verifying his hypothesis about the snowflake-like particles outside his window. Then as Carpenter began aligning the spacecraft and shifting control to the automatic mode, he suddenly found himself to be in trouble. The automatic stabilization system would not hold the 34- degree pitch and zero-degree yaw attitude. As he tried to determine what was wrong, he fell behind in his check of other items. When he hurriedly switched to the fly-by-wire control mode, he forgot to switch off the manual system. For about 10 minutes fuel from both systems was being used redundantly.

Finally, Carpenter felt that he had managed to align the spacecraft for the retrofire sequence. The Hawaiian communicator urged him to complete as much of the checklist as possible before he passed out of that site's communications range. Now Alan Shepard's voice from the Arguello, California, station came in loud and clear, asking whether the Aurora 7 pilot had bypassed the automatic retroattitude switch. Carpenter quickly acted on this timely reminder. Then the countdown for retrofire began. Because the automatic system was misbehaving, Carpenter was to push the button to ignite the solid-fuel retrorockets strapped to the heatshield. About three seconds after Shepard's call of "Mark! Fire One," the first rocket ignited and blew. Then the second and the third followed in reassuring succession. Carpenter saw wisps of smoke inside his cabin as the rockets braked him out of orbit.

Carpenter's attitude error was more than he estimated when he reported his attitude nearly correct. Actually Aurora 7 was canted at retrofire about 25 degrees to the right, and thus the reverse thrust vector was not in line with the flight path vector. This misalignment alone would have caused the spacecraft to overshoot the planned impact point by about 175 miles. But the retrorockets began firing three seconds late, adding another 15 miles or so to the trajectory error. Later analyses also revealed a thrust decrement in the retrorockets that was about three percent below nominal, contributing 60 more miles to the overshoot. If Carpenter had not bypassed the automatic retroattitude switch and manually ignited the retrorockets he could have overshot his pickup point in the Atlantic by an even greater distance.

Unlike Glenn, Carpenter had no illusion that he was being driven back to Hawaii at retrofire. Instead he had the feeling that Aurora 7 had simply stopped and that if he looked toward Earth he would see it coming straight up. One glance out the window, however, and the "impression was washed away." The completion of retrofire produced no changes the pilot could feel until his reentry began in earnest about 10 minutes later.

After the retrorockets had fired, Carpenter realized that the manual control system was still on. Quickly he turned off the fly-by-wire system, intending to check the manual controls.Although the manual fuel gauge read six percent left, there was, in fact, no fuel and consequently no manual control. So Carpenter switched back to fly-by-wire. At that time the automatic system supply read 15 percent, but the astronaut wondered how much really remained. Could it be only about 10 percent? With this gnawing doubt and realizing that it was still 10 minutes before .05-g time, Carpenter kept hands strictly off for most of his drifting glide. Whatever fuel there was left must be saved for the critical tumble. This 10-minute interval seemed like eternity to the pilot. The attitude indicators appeared to be useless, and there was little fuel to control attitude anyway. The only thing he trusted for reference was the view out of the window; using fly-by-wire sparingly he tried to keep the horizon in view. Although concerned about the fuel conservation problem, Carpenter gained some momentary relief from the fascinating vistas below: "I can make out very, very small - farm land, pasture land below. I see individual fields, rivers, lakes, roads, I think. I'll get back to reentry attitude."

Finally, Aurora 7 reached the .05-g acceleration point about 500 miles off the coast of Florida. As he began to feel his weight once again, Carpenter noted that the automatic fuel needle still read 15 percent. Within seconds the capsule began to oscillate badly. A quick switch to the auxiliary damping mode steadied the spacecraft. Grissom, the Cape communicator, reminded him to close his faceplate.

Aurora 7 was now in the midst of its blazing return to Earth. Carpenter heard the hissing sounds reported by Glenn, the cues that his ship was running into aerodynamic resistance. Immediately the capsule began to roll slowly, as programmed, to minimize the landing point dispersion. Carpenter looked out the window for the bright orange glow, the "fireball," as Glenn had described it, but there was only a moderate increase in light intensity. Rather than an orange glow, Carpenter saw a light-green glow apparently surrounding the cylindrical section. Was this radiant portion of the spacecraft ablating? Was the trim angle correct? The evenness of the oscillations argued to Carpenter that the trim angle was good. All the way through this zone Carpenter kept talking. Gradually it became difficult to squeeze the words out; the heaviest deceleration load was coming. The peak g period lasted longer than he had expected, and it took forceful breath control to utter anything.

The automatic fuel tank on Aurora 7 was emptied between 80,000 and 70,000 feet. As the plasma sheath of ionized air enveloped his spacecraft, communication efforts with Carpenter became useless, but the telemetered signals received by the radar stations at the Cape and on San Salvador predicted a successful reentry. The oscillations were increasing as the capsule approached the 50,000-foot level. Aurora 7 was swinging beyond the 10-degree "tolerable" limits. Carpenter strained upward to arm the drogue at 45,000 feet, but he forced himself to ride out still more severe oscillations before he fired the drogue parachute mortar at 25,000 feet. The chute pulsed out and vibrated like thin, quivering sheets of metal. At 15,000 feet Carpenter armed the main parachute switch, and at 9,500 feet he deployed the chute manually. The fabric quivered, but the giant umbrella streamed, reefed, and unfurled as it should. The rate of descent was 30 feet per second, the exact design specification. The spacecraft landing bag deploy was on automatic. Carpenter listened for the "clunk," heard the heatshield fall into position, and waited to hit the water. Aurora 7 seemed to be ready for the landing, and the recovery forces knew within a few miles the location of the spacecraft as radar tracking after retrofire had given and confirmed the landing point.

Splashdown was noisy but less of a jolt than the spaceman had expected. The capsule, however, did not right itself within a minute as it was supposed to do. Carpenter, noticing some drops of water on his tape recorder, wondered if Aurora 7 was about to meet the fate of Liberty Bell 7, and then sighed in relief when he could find no evidence of a leak. He waited a little longer for the spacecraft to straighten up, but it continued to list to his left. Grissom's last transmission from Mercury Control had told Carpenter that it would take the pararescue men about an hour to reach him, and the astronaut realized that he had evidently overshot the planned landing zone. When he failed to raise a response on his radio, he decided to get out of the cramped capsule. Then he saw that the capsule was floating rather deeply, which meant that it might be dangerous to remove the hatch. Sweating profusely in the 101-degree temperature of the cabin, he pulled off his helmet and began the job of egress as it had been originally planned. Carpenter wormed his way upward through the throat of the spacecraft, a hard, hot job made bearable by his leaving the suit circuit hose attached and not unrolling the neck dam. He struggled with the camera, packaged life raft, survival kit, and kinky hose before he finally got his head outside.

Half out of the top hatch, Carpenter rested on his elbows momentarily, released the suit hose but failed to deploy the neck dam and lock the hose inlet, and surveyed the sea. Lazy swells, some as high as six feet, did not look too forbidding. So he carefully laid his hand camera on top of the recovery compartment, squeezed out of the top, and carefully lowered himself into the water, tipping the listing spacecraft slightly in the process. Holding onto the capsule, he was able to easily inflate the life raft - upside down. By this time, feeling some water in his boots, he secured the hose inlet to the suit. He then held on to the spacecraft's side and managed to flip the raft upright. After crawling onto the yellow raft, he retrieved the camera, unrolled the suit neck dam, and prepared to wait for as long as it took the recovery searchers to find him. The recovery beacon was operating and the green dye pervaded the sea all around him.

The status of Carpenter and Aurora 7 was unknown to the public. Everyone following the flight by radio or television knew that the spacecraft must be down. But was the pilot safe? What the public did not know was that one P2V airplane had received the spacecraft's beacon signal from a distance of only 50 miles, while another plane had picked up the signal from 250 miles. Aurora 7's position was well known to the recovery forces in the area. About eight minutes before the spacecraft landed, an SA-16 seaplane of the Air Force Air Rescue Service had taken off from Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, for the radar-predicted landing point. Three ships - a Coast Guard cutter at St. Thomas Island, a merchantman 31 miles from the plotted point, and the destroyer Farragut about 75 miles away to the southwest - were in the vicinity of the impact point. But it would certainly take longer than an hour for any recovery unit to reach the site. Since Carpenter's raft had no radio, the drama was heightened. What exactly had happened to Carpenter after his landing was known only to the astronaut and perhaps to a few sea gulls and sea bass.

Carpenter settled down on his raft and waited patiently for his rescuers. He mused over some seaweed floating nearby and "a black fish that was just as friendly as he could be - right down by the raft." In time, 36 minutes after splashdown, he saw two aircraft, a P2V and, unexpectedly, a Piper Apache. The astronaut watched the planes circle, saw that the Apache pilot was photographing the area, and knew that he had been found. Twenty minutes later several SC-54 aircraft arrived, and one dropped two frogmen, but Carpenter, watching other planes, did not see them bail out.

Airman First Class John F. Heitsch, dropping from the SC-54 transport about an hour and seven minutes after Carpenter had first hit the water, missed the life raft by a considerable distance. Releasing his chute harness, he dove under the waves and swam the distance to the side of Carpenter's raft. "Hey!" called the frogman to the spaceman. Carpenter turned and with complete surprise asked, "How did you get here?" Shortly thereafter a second pararescue man, Sergeant Ray McClure, swam alongside and clutched the astronaut's raft. The two frogmen quickly inflated two other rafts and locked them to the spacecraft. McClure and Heitsch later described the astronaut as smiling, happy, and not at all tired. The pilot broke out his survival rations and offered some to the two Air Force swimmers, who declined the space food but drank some space water.

The three men, still without radio contact, perched on the three rafts and watched the planes circling above. One plane dropped the spacecraft flotation collar, which hit the water with a loud bang, breaking one of its compressed-air bottles. The swimmers retrieved and attached the flotation collar with only its top loop inflated and then crawled back onto their rafts. Shortly a parachute with a box at the end came floating lazily down some distance from the spacecraft. The men on the rafts supposed this was the needed radio, and one of the frogmen swam a considerable distance to get it. He returned with the container, opened it, and found that there was no radio inside, only a battery. Later Carpenter laughingly declined to repeat the swimmer's heated remarks.

The Air Force SA-16 seaplane from Roosevelt Roads arrived at the scene about an hour and a half after the spacecraft landed in the Atlantic. To the SA-16 pilot the sea seemed calm enough to set his craft down upon and pick up the astronaut, but the Mercury Control Center directed the seaplane not to land. As later depicted by the news media and thoroughly discussed in Congress, this delay grew out of traditional rivalry between the Air Force and the Navy. Brigadier General Thomas J. Dubose, a former commander of the Air Rescue Service, wrote to Florida's United States Senator Spessard L. Holland, charging that Carpenter floated in the raft an hour and20 minutes longer than was necessary. D. Brainerd Holmes, a NASA official, testified at the hearings that Admiral John L. Chew, commander of the Project Mercury recovery forces, feared the seaplane might break apart if it landed on the choppy waters. Because of this, according to Holmes, the decision had been made to proceed with helicopter and ship pickup as originally planned.

After three hours of sitting on the sea in his raft, Carpenter was picked up by an HSS-2 helicopter, but either the rotorcraft settled as a swell arose or the winch operator accidentally lowered away, and the astronaut was dunked. Up went his arm and the hand holding the camera to keep the precious film dry. With nothing else amiss, Carpenter was hoisted aboard the helicopter, a drenched but happy astronaut. Richard A. Rink, a physician aboard, described Carpenter as exhilarated. The astronaut draped one leg out of the helicopter and, by cutting a hole in his sock, drained most of the water from his pressure suit. He then stood up and proceeded to pace around, sometimes settling in a seat, and intermittently talking about his flight. Carpenter arrived aboard the carrier Intrepid some four hours and 15 minutes after his return to Earth. The medical examinations began immediately but were interrupted when the astronaut was called to the phone to receive what was by now President Kennedy's traditional congratulatory call. The President expressed his relief that Carpenter was safe and well, while Carpenter gave his "apologies for not having aimed a little better on reentry." From the Intrepid the astronaut was flown to Grand Turk Island, where, as Howard A. Minners, an Air Force physician assigned to Mercury, described it, Carpenter wanted to stay up late and talk.

Aurora 7, picked up by the destroyer Pierce, was returned to Cape Canaveral the next day. When retrieved, the spacecraft was listing about 45 degrees compared to the normal 15 to 20 degrees, and it contained about 65 gallons of sea water, which would hamper the inspection and postflight analyses. Carpenter recalled two occasions on which the spacecraft had shipped small amounts of water, but he was unable to explain the larger amount found by the pickup crew. The exterior of the spacecraft showed the usual bluish and orange tinges on the shingles, several of which were slightly dented and scratched as after previous missions. Since there was no evidence of inflight damage, these slight scars presumably were the result of postflight handling. The spacecraft heatshield and main pressure bulkhead were in good condition except for a missing shield center plug, which had definitely been in place during reentry. Some of the honeycomb was crushed, resulting in minor deformation of the small tubing in that area. Heitsch and McClure, the pararescue men, had reported the landing bag in good condition, but when it was hauled out of the water most of the straps were broken, probably by wave action. All in all, Aurora 7 was in good shape and had performed well for Project Mercury's second manned orbital flight.

The postflight celebrations and honors followed the precedents and patterns established by Glenn's flight. Administrator Webb presented to Carpenter and Williams NASA Distinguished Service Medals in a ceremony at the Cape. Carpenter also learned of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev's cabled congratulations. Then the astronaut's hometown, Boulder, Colorado, gave him a hero's welcome. After being awarded a degree by the University of Colorado, where he had lacked a credit in a heat-transfer course, the astronaut facetiously commented that the blazing MA-7 reentry surely qualified him as a master in the field of thermodynamics. Memorial Day found the pilot in Denver, where a crowd of 300,000 people cheered and honored him. The next day he returned to work at Langley, where exhaustive technical debriefings were held to glean all the knowledge possible from MA-7.

In these postflight sessions the astronaut insisted that he knew what he wanted to do at all times, but that every task took a little longer than the time allotted by the flight plan. Some of the equipment, he said, was not easy to handle, particularly the special films that he had to load into a camera. As a consequence he had been unable to get all the pictures the Weather Bureau had requested for its satellite photography program. Moreover, the flight plan that had been available during training was only a tentative one, and the final plan had been completed only a short while before he suited up for the launch. Carpenter felt that the completed plan should be in the astronaut's hands at least two months before a scheduled flight and that the flight agenda should allow more time for the pilot to observe, evaluate, and record. When asked about fuel consumption by the high thrusters, Carpenter replied that the 24-pounders were unnecessary for the orbital phase of a flight.

The astronaut recommended that some method be devised for closing off the high thrusters while the automatic control system was in operation. He granted that on the fly-by-wire, low-thruster operation, the spacecraft changed its attitude slowly, as was shown by the needle movement, and that the pilot would have to wait momentarily to pick up the desired attitude change rate. For tracking tasks, however, the manual- proportional mode served well; attitude changes could be made with only a gentle touch of the handcontroller. Talking with newsmen after the flight, Carpenter assumed full responsibility for his high fuel consumption. He pointed out, however, that what he had learned would be valuable for longer Mercury missions.

As mid-year 1962 approached, Project Mercury faced yet another crossroad. Had enough been learned during the two three-orbit flights to justify going on to longer missions? Joe W. Dodson, a Manned Spacecraft Center engineer, speaking before the Exchange Club of Hampton, Virginia, indicated that the MSC designers and planners and the operations team were well pleased with the lessons derived from Glenn, from Carpenter, and from their spacecraft. They were pleased especially at how well the combination of man and machine had worked.

Shortly thereafter, the press began to speculate that NASA might try a one-day orbital flight before 1963. Administrator Webb, however, sought to scotch any premature guesswork until Gilruth and his MSC team could made a firm decision. He stated that there might well be another three-orbit mission, but added that consideration was being given to a flight of as many as six orbits with recovery in the Pacific. Robert C. Seamans, Jr., NASA's "general manager," told congressional leaders that if a decision had to be made on the day on which he was speaking, it would probably be for another flight such as Glenn and Carpenter had made. But many members of Congress wanted to drop a third triple-orbit mission in favor of a flight that would come closer to or even surpass Gherman Titov's 17-orbit experience.

On June 27, 1962, NASA Headquarters ended the speculation by announcing that Walter Schirra would pilot the next mission for as many as six orbits, possibly by the coming September, with L. Gordon Cooper as alternate pilot. The original Mercury objectives had been met and passed; now it was time to proceed to new objectives - longer missions, different in quality as well as quantity of orbits. Project Mercury had twice accomplished the mission for which it was designed, but in so doing its end had become the means for further ends.

More at: Mercury MA-7.

Family: Manned spaceflight. People: Carpenter. Country: USA. Spacecraft: Mercury. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral. Agency: NASA.

| Mercury MA-7 Carpenter after his rescue Credit: NASA |

1960 November 1 - .

- Goddard Mercury computing and communications center operational. - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. The Goddard Space Flight Center computing and communications center became operational. . Additional Details: here....

1961 November 15 - .

- Mercury spacecraft No. 18 was delivered to Cape Canaveral - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. Mercury spacecraft No. 18 was delivered to Cape Canaveral for the second manned (Carpenter) orbital flight, Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7)..

1962 February 25 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas D.

- Factory roll-out inspection of Mercury Atlas launch vehicle 107-D. - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. Factory roll-out inspection of Atlas launch vehicle 107-D, designated for the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission, was conducted at Convair..

1962 March 4-5 - .

- Mercury MA-7 water-egress exercises. - .

Nation: USA.

Flight: Mercury MA-7.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

Scott Carpenter and Walter Schirra, designated (but not publicly) as pilot and backup pilot, respectively, for the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission, underwent water-egress exercises. Several side-hatch egresses were made in conjunction with helicopter pickups.

1962 March 15 - . LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas D.

- Carpenter replaces Slayton on Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. NASA Headquarters publicly announced that Scott Carpenter would pilot the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission replacing Donald Slayton. The latter, formerly scheduled for the flight, was disqualified because of a minor erratic heart rate..

1962 March 22 - .

- NASA Project Mercury Advance Recovery Requirements - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. Manned Spacecraft Center personnel briefed the Chief of Naval Operations on the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) flight and ensuing Mercury flights. This material was incorporated in a document entitled, 'NASA Project Mercury Advance Recovery Requirements.'.

1962 April 15 - .

- Mercury MA-7 water exercise training program - .

Nation: USA.

Flight: Mercury MA-7.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

Scott Carpenter and Walter Schirra, designated as pilot and backup pilot, respectively, for the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission, underwent a water exercise training program to review procedures for boarding the life raft and the use of survival packs.

1962 May 4 - .

- Simulated Mercury MA-7 mission exercise. - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. Scott Carpenter, designated as the primary pilot for the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital flight completed a simulated MA-7 mission exercise..

1962 May 7 - .

- Mercury MA-7 delays - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. NASA announced that the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital flight would be delayed several days due to checkout problems with the Atlas launch vehicle..

1962 May 15 - .

- Carpenter named for Mercury MA-7 - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. Scott Carpenter, designated as the primary pilot of the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital flight, flew a simulated mission with the spacecraft mated to the Atlas launch vehicle..

1962 May 17 - .

- Mercury MA-7 postponed a second time - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. The Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission was postponed a second time because of necessary modifications to the altitude-sensing instrumentation in the parachute-deployment system..

1962 May 19 - .

- Mercury MA-7 postponed a third time - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. A third postponement was made for the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) flight mission due to irregularities detected in the temperature control device on a heater in the Atlas flight control system..

1962 May 24 - . 12:45 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC14. LV Family: Atlas. Launch Vehicle: Atlas D.

- Mercury MA-7 - .

Call Sign: Aurora 7. Crew: Carpenter.

Backup Crew: Schirra.

Payload: Mercury SC18. Mass: 1,349 kg (2,974 lb). Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned spacecraft. Flight: Mercury MA-7.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

Duration: 0.21 days. Decay Date: 1962-05-24 . USAF Sat Cat: 295 . COSPAR: 1962-Tau-1. Apogee: 260 km (160 mi). Perigee: 154 km (95 mi). Inclination: 32.50 deg. Period: 88.50 min.

BSD's 6555th Aerospace Test Wing launched Mercury/Atlas 7 (MA-7), "Aurora 7", into orbit carrying Navy Commander M. Scott Carpenter. This was the second U.S. manned orbital flight mission. Scott Carpenter in Aurora 7 is enthralled by his environment but uses too much orientation fuel. Yaw error and late retrofire caused the landing impact point to be over 300 km beyond the intended area and beyond radio range of the recovery forces. Landing occurred 4 hours and 56 minutes after liftoff. Astronaut Carpenter was later picked up safely by a helicopter after a long wait in the ocean and fears for his safety. NASA was not impressed and Carpenter left the agency soon thereafter to become an aquanaut.

1962 August 21 - .

- Technical conference on the Mercury MA-7 mission - . Nation: USA. Flight: Mercury MA-7. Spacecraft: Mercury. A conference was held at the Rice Hotel, Houston, Texas, on the technical aspects of the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission (Carpenter flight)..

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use