Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Navaho G-26

Navaho G-26 Launch Navaho G-26 Launch RISE 1 Credit: Tom Johnson |

AKA: Navaho II;W13;XSM-64;XSSM-A-4. Status: Retired 1958. First Launch: 1956-11-06. Last Launch: 1958-11-18. Number: 11 . Payload: 3,150 kg (6,940 lb). Thrust: 1,067.40 kN (239,961 lbf). Gross mass: 71,881 kg (158,470 lb). Height: 28.00 m (91.00 ft). Diameter: 1.76 m (5.77 ft). Span: 8.72 m (28.60 ft). Apogee: 25 km (15 mi).

Development History

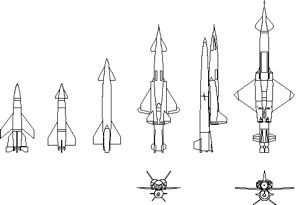

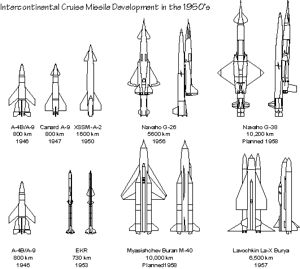

North American had been developing a 1600-km range, Mach 3 missile for the US Air Force since March 1946. The vehicle started out as a derivative of the German A9 boost-glide vehicle, but soon developed completely revised aerodynamics, guidance, and improved propulsion. In February 1948 this project was redefined by the customer as only the first step of a revised three-phase program for a family of vehicles using a rocket booster and ramjet cruise. Track, air, and vertical pad launch were to be studied. Phase two would produce a missile that could carry a 1350 kg warhead to a 3200 to 4800 km range. By July 1948 the preferred long-range Navaho configuration was a delta-winged, recoverable aircraft-type booster looking very much like the B-70 bomber of the 1960's or the reusable boosters of the original space shuttle designs. The cruise stage used a single enormous ramjet engine with a nose intake.

In May 1949 North American settled on a revised design for the long-range versions of the Navaho. It consisted of a tandem in-line boost stage with a single-ramjet cruise stage atop it. In April 1950 the Air Force canceled the 1600-km range Phase I version of the Navaho. Formal redirection of the program came in July 1950. The final missile intercontinental missile would be developed in a new three-phase program. In Phase 2, the G-26 test vehicle, a 2/3 scale version, would test the vertical launch booster, and a steel-structure ramjet-powered cruise vehicle that would reach Mach 2.75 and a range of 2300 km. By March 1951 the development of the 333 kN XLR-43-NA-1 rocket engine for the now-canceled 1600-km range version was completed; but this was just a way-station to the more powerful LR-71-NA-1 530 kN engine required for the Phase II and III missiles.

The course of 1952 saw a wide range of testing activities. A 20-inch diameter ramjet, a subscale version of the 40-inch engine for the Navaho, was flown on Lockheed's X-7 rocket. Of the seven launches, only one was completely successful, and two partially successful. The G-26 version of Navaho reached the mock-up stage. In June a test version of the 540 kN combustion chamber for missile was run. This was the most powerful ever tested, but still used the double-walled combustion chamber design of the LR43 rather than the brazed tubular wall construction planned for the production LR71. But the first complete prototype was first operated on 19 November. By the end of the year the drawings for the G-26 were released to the shop.

On 23 December the USAF released the full-scale development contract for the Navaho G-26, consisting of 10 cruise missiles, 13 boosters, and five N-6 stellar-inertial navigation systems (early flights would be radio-controlled). First delivery was scheduled for 1953 and first launch February 1956.

But early in 1953 another technical improvement was deemed necessary, and this would impact the schedule just agreed. North American's rocket group had begun a Rocket Engine Advancement Program, to identify improved rocket technology. One early conclusion was that the performance and logistics could be significantly improved by shifting from alcohol to kerosene fuel. The decision was made to change the propellants for both the Navaho G-26 test vehicle and the G-38 production booster. The LR71 engine, improved and modified to burn kerosene, would be designated LR83. This meant a delay to Navaho, but would be the basic engine that would power the Thor, Jupiter, Atlas, Saturn I, and Delta rockets into the next century. It should be noted that most references state that the Navaho was flown with the LR71 alcohol engine; but it is quite clear that it flew with the LR83 kerosene engine, or at least with LR71 engines modified to burn kerosene.

North American also began operations at Cape Canaveral in 1953, building two missile assembly buildings, a vertical launch facility for the G-26 (LC9) and a 70 m x 3000 m landing strip (the 'Skid Strip') to recover the reusable G-26 test vehicles. North American tripled its field office staff at the Cape from 22 to 77 people in 1954. It also began installing equipment in the guidance laboratory, the blockhouse and the Navaho flight control building even before construction of those facilities was completed. N-6 navigation system flight testing began aboard a T-29 in May 1954.

On 11 January 1955 the Air Force expressed its confidence in the missile by placing the second G-26 second production contract. This added 12 more cruise stages, 21 boosters, and 6 N6 navigation systems, bringing the total procured to 22 cruise stages, 34 boosters, and 11 navigation systems. Support facilities were at the Cape were completed in the last half of 1955. By the middle of 1956, North American had 605 people working on the Navaho program at the Cape, but problems with the auxiliary power unit delayed the Navaho G-26's first launch for six months. When the first vehicle finally made it into the air, it exploded 26 seconds into the flight. Three more Navahos were launched over the next seven months with equally dismal results. In addition to those failures, the first in a series of 2,800 km long auto-navigator test flights was attempted ten times in the first three months of 1957 without a single launch.

More promising were successful static tests of the booster rockets and North American's isolation of problem areas revealed in the first four flights. But while the "never-go-Navaho" sat on the pad or failed in flight, the first Jupiter, Thor, and Atlas ballistic missiles began test in the spring of 1957. They were equally unsuccessful at first, but a Jupiter made a full-range 2100-km flight on 31 May. The Army had already demonstrated the necessary re-entry vehicle technology on launches of the 'Jupiter-A' multi-stage versions of the Redstone. It was clear that these ballistic missiles, each little more complex than the booster stage of Navaho alone, could deliver a nuclear warhead over the same ranges - at seven times the speed.

But it was still a surprise when Air Force Headquarters terminated the Navaho development program on 12 July 1957. 4,705 employees were laid off the day the termination notice was received via an announcement over the public address system to "stop what you are doing, proceed to the nearest exit, and deposit your badge in the bin indicated". By the end of the month the total staff laid off at North American alone amounted to 15,600 employees.

Because the auto-navigator showed promise for use on other missiles, the Air Force authorized continuation of flight test of existing assets. Engineering staff was kept on at Cape Canaveral to launch the five completed G-26 missiles, at a total cost of $4.9 million. These were flown through February 1958, and were somewhat more successful than the earlier series, with one missile managing to reach a range of 2000 km before its ramjets failed.

Seven further completed G-26 Navahos were to be tested in support the of North American's B-70 bomber and F-108 long-range interceptor programs. But after two unsuccessful launches in late 1958 that project was completely canceled at the insistence of the B-70 Weapons System Project Office.

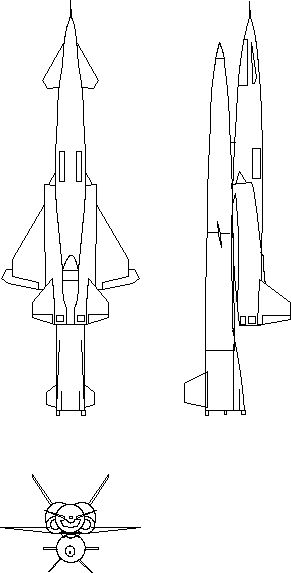

Technical Description

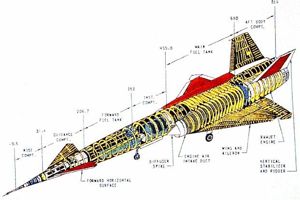

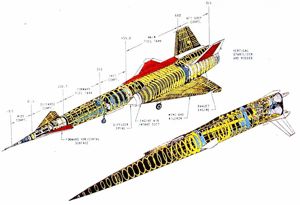

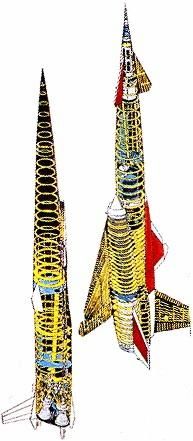

The booster was designed to take the cruise stage to Mach 2.75 at 13 km altitude, at which point it would cut off. It would separate 1.5 seconds later at 14.6 km altitude, then fall back to earth a short distance downrange from the launch site. The complex conical structure was made primarily of 20-24ST aluminum alloy, heliarc-welded and chem-milled to 3 mm thickness between the weld lands. The liquid oxygen tank was forward, a largely monocoque structure with longerons running aft of the forward cruise stage attachment fitting. It had a capacity of 18,090 kg. Tank pressurization was by gaseous oxygen generated by the inevitable boil-off of the cryogenic liquid; but red fiberglass insulation was applied to the external skin of the booster outside of the liquid oxygen tank to minimize this boil-off. Aft of the oxygen tank was the fuel tank, a semi-monocoque structure that carried most of the loads during ascent. This had a capacity of 12,950 kg of fuel. The liquid oxygen line ran through the middle of the tank, from the oxygen tank above to the engines below. Two small fixed separation fins were attached to the intertank structure to ensure the booster would fly away from the cruise stage once released.

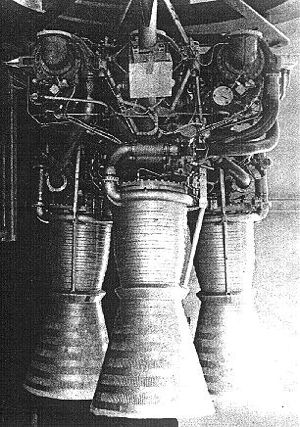

Aft of the fuel tank was the engine bay, with two fixed LR71 engines. Thrust vector control was by V-2-style graphite vanes that were moved into the exhaust. Two large fixed canted fins were attached to the engine bay, providing vehicle stability during ascent. After the decision was made to upgrade the engines from alcohol to kerosene fuel, with a 7% improvement in performance, some detailed design changes had to be made to the design of the fuel tank. This resulted in a delay of final drawing release to June of 1954, and delayed static testing of the modified booster stage to December 1954.

The cruise stage used the same configuration as the turbojet-powered X-10 test vehicle - delta wing, dual engines and vertical stabilizers, forward horizontal control surfaces. Dimensionally it was just 2% larger than the X-10, but differed in detail, reflecting the higher altitude, higher speed, and different type of engines used. The canted twin vertical stabilizers were larger and farther aft. The wings had a notched appearance, with large lobed rudders that extended over the wingtip. An inlet between the vertical stabilizers fed the Auxiliary Power Unit, required since ramjets had no rotating machinery to be used for power generation. From fore to aft the fuselage consisted of a nose compartment; the guidance compartment, which housed the N-6 inertial navigation system and PIX10 autopilot; the forward fuel tank; the instrument compartment, used for test and telemetry equipment in the flight test version but capable of housing a 3150-kg, 2.15-m long W-4 or W-13 nuclear weapon; the main fuel tank; and the aft body compartment, which housed the APU. The cruise stage had a maximum capacity of 24,070 liters of JP-5 kerosene fuel.

The inlets for the engines were substantially larger than the X-10, and used diffuser spikes instead of the X-10's convergent/divergent inlet duct. The fuselage was of predominately aluminum structure, as the X-10, but used titanium in the hotter nose, wing leading engines, and engine exhaust areas. In sustained Mach 2.75 cruise the vehicle would reach temperatures of 270 deg C.

G-26 Navahos would be flown using both a radio-control system and prototypes of the N-6 stellar-inertial system planned for the operational missile. The autopilot and radio-control system and its gyroscopic platform had been proven in tests of the X-10 drone. The XN-6 stellar-inertial navigation system used paired counterrotating gyroscopes to compensate for the precession errors that were seen in the earlier single-gyro-per-axis XN-2 design. It also introduced hydrodynamic bearing gyros in place of the XN-2's air bearings.

Development Cost $: 679.800 million in 1959 dollars. Flyaway Unit Cost 1985$: 5.000 million in 1956 dollars. Maximum range: 4,900 km (3,000 mi). Number Standard Warheads: 1. Standard warhead: W13. Boost Propulsion: Liquid rocket, 2 x Lox/Kerosene. Cruise Thrust: 66.700 kN (14,995 lbf). Cruise engine: XRJ47-W-5. Maximum speed: 3,100 kph (1,900 mph). Total Number Built: 18.

Stage Data - Navaho G-26

- Stage 1. 1 x G-26 Navaho Booster. Gross Mass: 42,403 kg (93,482 lb). Empty Mass: 11,337 kg (24,993 lb). Thrust (vac): 1,204.119 kN (270,697 lbf). Isp: 273 sec. Burn time: 76 sec. Isp(sl): 242 sec. Diameter: 1.76 m (5.77 ft). Span: 1.76 m (5.77 ft). Length: 23.26 m (76.31 ft). Propellants: Lox/Alcohol. No Engines: 2. Engine: XLR-83-NA-1. Other designations: XB-64, XSM-64. Status: Out of Production. Comments: Burns out at altitude 13,000 m, Mach 3.

- Stage 2. 1 x G-26 Navaho Missile. Gross Mass: 29,478 kg (64,987 lb). Empty Mass: 9,977 kg (21,995 lb). Thrust (vac): 66.704 kN (14,996 lbf). Isp: 1,200 sec. Burn time: 6,500 sec. Diameter: 1.55 m (5.08 ft). Span: 8.71 m (28.57 ft). Length: 20.67 m (67.81 ft). Propellants: Air/Kerosene. No Engines: 2. Engine: XRJ47-W-5. Other designations: XB-64, XSM-64. Status: Out of Production. Comments: Separates from booster at 14,600 m, Mach 3. Mach 2.75 cruise, 5,600 km range, payload 2500 kg in 2.59 m x 1.50 m compartment.

Family: IRCM, US Cruise Missiles. Country: USA. Engines: XLR83-NA-1, XRJ47-W-5. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral, Cape Canaveral LC9, Cape Canaveral LC10. Stages: G-26 Booster, Navaho G-26 AV. Agency: North American.

| Navaho G-38 Engine Navaho G-38 3 Engine Cluster |

| Navaho development Navaho development sequence Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Navaho vs Burya Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Navaho G-26 3 View Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Navaho Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Navaho G-26 Navaho G-26 160 pixel Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Navaho G-26 on Pad 9 Navaho G-26 on Pad 9A Credit: Tom Johnson |

| Navaho G-26 Navaho launch of 22 March 1957 |

| Navaho G-26 Navaho launch of 22 March 1957 |

| Navaho by Night Navaho launch complex at night |

| Navaho G-26 Booster Navaho G-26 Booster Cutaway Credit: Tom Johnson |

| Navaho G-26 Missile Navaho G-26 Missile Cutaway Credit: Tom Johnson |

| Navaho G-26 Cutaway |

| Navaho G-26 Cutaway |

1950 August - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Air-launched Navaho dropped - . Nation: USA. Program: Navaho. All work on the air-launched versions of Navaho was stopped. North American was to concentrate on rocket-boosted missiles..

1950 October - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Wright gets G-26 ramjet contract - . Nation: USA. Program: Navaho. The engine was designated XRJ47-W-1..

1951 December - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

1952 June - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

1952 December - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- G-26 drawing release - . Nation: USA. Program: Navaho. The drawings were released to the shop and fabrication of component parts began..

1952 December 23 - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 contract - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Navaho.

The USAF released the full-scale development contract for the Navaho G-26, consisting of 10 cruise missiles, 13 boosters, and five N-6 stellar-inertial navigation systems (early flights would be radio-controlled). First delivery was scheduled for 1953 and first launch February 1956.

1954 January - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 static tests begin - . Nation: USA. Program: Navaho. Vehicle 3 is placed in a static test fixture at Downey..

1955 January 11 - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 second production contract - . Nation: USA. Program: Navaho. This added 12 more cruise stages, 21 boosters, and 6 N6 navigation systems, bringing the total procured to 22 cruise stages, 34 boosters, and 11 navigation systems..

1955 March - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 static test article ruptures - . Nation: USA. Program: Navaho. During simulated propellant loading (with water) at Downey, a crack opened at one of the cruise stage mounting points. The water drained out of the tank, creating a vacuum, followed by implosion of the oxygen tank..

1955 June - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

1956 March 26 - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

1956 April 7 - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- First Navaho G-26 flight cruise stage delivered to Cape Canaveral - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Navaho.

However continued problems and late delivery of the Auxiliary Power Unit pushed the planned first launch date from May to July. Three APU's were shipped before one was accepted. Attempts for a pad static test of the boost engines began in August. Seven attempts were made through the end of September. The fiberglass liquid oxygen tank insulation delaminated during the first propellant loading; chair springs were used to hold it on in subsequent tests. Helium lines ruptured; the engine was shut off after three seconds due to high gas generator temperatures; the G-26 cruise stage's landing gear deployed internally, cracking the skin; finally at the end of September a 34-second test was completed, but on ground power after the APU failed. The missile was pulled from the flight order and the first Broomstick flight canceled.

1956 November 6 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Pitched up, disintegrated at T+26 seconds - pitch rate gyro installed backwards.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 1 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 2.00 km (1.20 mi).

Continuing problems with APU reliability delayed the launch to November. Various problems extended the countdown from the planned 7 hours 30 minutes to 14 hours 30 minutes. Successful launch, then vehicle pitched up and disintegrated 26 seconds after launch, impacting 4 km down range. It was found the pitch rate gyro had been installed backward.

1957 March 1 - . LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho launch scrub - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Navaho.

There were ten attempts to launch Navaho G-26 vehicle number 4 since the first static firing test on 3 December 1956 had been unsuccessful. The vehicle was plagued with problems with the engines and APU, resulting in engine burn-through, engine non-ignition, as well as other unrelated problems - ramjet engine fires, destruct package failures. The vehicle was pulsed from the launch order.

1957 March 22 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Ground pod failed to jettison; booster damaged and did not achieve speed/altitude required for cruise stage ignition.. Failed Stage: 1.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 2 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 9.00 km (5.50 mi).

G-26 number two / booster 6 lifted off after a 9 hour 48 minute countdown with nearly five hours of holds, on the first attempt after two successful static firings. However failure of a launch lanyard meant the kerosene start-pod on the booster remained attached. This sheared off at 4500 m, causing extensive booster damage. Thrust decayed. The cruise stage separated at Mach 1.3 at 28,300 feet, but this was below ramjet ignition speed. However the pilot on the ground was able to assume radio control of the vehicle, and flew it in a glide over the ocean, even demonstrating landing gear deployment before it pancaked into the water.

1957 April 25 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Booster shut down 1 m over the pad due to incorrect shutdown timer signal - exploded on pad.. Failed Stage: 1.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 3 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 0 km (0 mi).

Vehicle 4 was still not ready for the first Broomstick flight, so vehicle 5 was substituted. It took five attempts before a 15.6 second static test cleared the booster for launch on 29 March. 8 hours and 42 minutes of hold stretched the five-hour countdown out into the evening. The booster ignited, rose 1.3 m, then shut down. The vehicle fell back onto the pad, exploding. Cause was a 15-second timer that was supposed to shut the engines down 15 seconds after the vehicle hold-downs released if a lanyard had not been pulled free of the vehicle as it rose off the ground. The 15 seconds had been reached before the lanyard pulled free, but by then the vehicle had risen off the pad. This made 15 attempts to launch a Navaho, with only two booster ignitions, both resulting in loss of the vehicle. The Northrop crews at the Cape dubbed their competitor the "Never-Go Navaho" to counter jibes directed at them about the "Snark-infested waters" off the launch area. The Air Force was not amused, and had a tiger-team review of the G-26 on a system-basis which recommended several procedures. Meanwhile G-38 launch plans were further delayed over internal USAF wrangles over launch facility construction.

1957 June 26 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: One booster engine failed during ascent; did not achieve speed/altitude required for cruise stage ignition.. Failed Stage: 1.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 4 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 12 km (7 mi).

The missile launched from the repaired LC-9 on the third attempt. At T+42 seconds, Mach 1.63, and 7,000 m altitude, a fire occurred in the engine compartment after a failure of a regenerative cooling valve to the gas generator. The turbopump shut down, and one engine went out. Nevertheless the vehicle continued, first on one engine, then coasting, to 12,000 m altitude, and the booster separated successfully. But the cruise stage was below ramjet ignition velocity. Again ground control could bring the cruise stage under control as a glider, flying it to an impact 87 km downrange

1957 August 12 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC10. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 5 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 25 km (15 mi).

After a 15 hour 18 minute countdown G-26 number four finally left the pad. The boost phase was completed successfully; but then a guidance system malfunction prevented the cruise stage from separating from the booster until an altitude of 25 km was reached. However the autopilot successfully overcome drastic pitch oscillations created by the lofted trajectory, and the ramjets were successfully ignited. The stage cruised at Mach 2.93 for 280 km. However then the vehicle began drifting off course. The ground pilot banked, but the fuselage screened the airflow to the left ramjet intake, resulting in that engine flaming out. The vehicle lost speed and altitude, and the right engine flamed out a minute later. The missile was ordered into a terminal dive, impacting 425 km downrange.

1957 September 18 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 6 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 23 km (14 mi).

The booster worked well, the cruise stage separated at 23.5 km altitude. The ramjets ignited, and the cruise stage accelerated to Mach 3.5. After 15 minutes, the missile began drifting off-course, and ground control took over and banked the missile. One of the ramjets flamed out, and the missile was commanded into a terminal dive and impacted 930 km downrange.

1957 November 13 - . 17:28 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Destroyed by range safety after telemetry dropped out at T+75 seconds.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 7 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 20 km (12 mi).

The booster functioned well, and the cruise stage separated at 20.4 km altitude and Mach 3.24. The ramjets ignited, but before the ground knew that, the telemetry dropped out completely due to a faulty voltage regulator on the missile. Range safety ordered the missile's self destruction at T+75 seconds.

1958 January 10 - . 19:38 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 8 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 22 km (13 mi).

The booster functioned well, the cruise stage separated at 22 km and Mach 3.15. The ramjets ignited and the cruise stage flew at a sustained speed of Mach 2.8 for forty minutes over a distance of 2000 km. Then the vehicle began a turn for the return to the Cape for recovery. However it seemed the turn was not fast enough; ground control took over, and yet again the right ramjet flamed out in a ground-piloted bank. The missile was commanded into a terminal dive at sea.

1958 February 26 - . 17:22 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Booster shut down at T+20 seconds.. Failed Stage: 1.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 9 - . Nation: USA. Agency: USAF. Apogee: 2.00 km (1.20 mi). The booster shut down at T+20 seconds in the flight. The vehicle was self-destructed by range safety before separation of the cruise stage had occurred..

1958 September 11 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Booster performed well, but cruise stage never ignited due to fuel system failure..

- Navaho G-26 Flight 10 RISE-1 - .

Nation: USA.

Agency: USAF.

Apogee: 25 km (15 mi).

North American had received funding to fly seven surplus G-26 missiles in a program dubbed RISE (Research Into Supersonic Environment), ostensibly to obtain real-world data on Mach 3 flight for the F-108 interceptor and B-70 bomber that they were developing for the USAF. On this first attempt, the booster performed well, but after separation the cruise stage fuel system failed, and ramjet ignition never occurred. The cruise stage impacted 150 km downrange.

1958 November 18 - . 21:03 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC9. LV Family: Navaho. Launch Vehicle: Navaho G-26. FAILURE: Disintegrated at moment of booster shutdown.. Failed Stage: 1.

- Navaho G-26 Flight 11 RISE-2 - . Nation: USA. Agency: USAF. Apogee: 23 km (14 mi). The vehicle disintegrated at 23.5 km altitude at the time of booster shutdown and cruse stage separation. The USAF canceled further RISE flights and this definitively marked the end of the Navaho..

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use