Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Von Braun Mars Expedition - 1952

Mars 1946

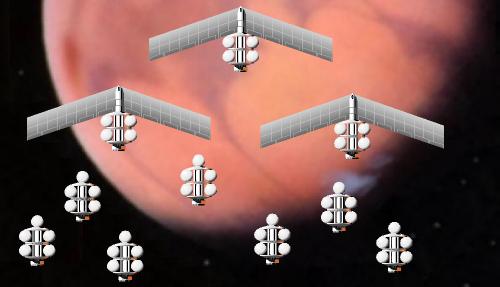

Von Braun's enormous 1946 expedition approaches Mars. The three winged landing boats are accompanied by seven cargo/passenger ships.

Credit: © Mark Wade

Status: Study 1952. Gross mass: 37,200,000 kg (82,000,000 lb).

He published his calculations in 1952, and they subsequently reached a wide audience in Collier's magazine, a series of books, and the Walt Disney television program. What is astonishing is that Von Braun's scenario is still valid today.

In 1948, with the US Army's V-2 test project winding down, Wernher Von Braun was ensconced in isolated Fort Bliss. He had, unusually, some time on his hands. He occupied himself by writing a novel concerning an expedition to Mars, grounded on accurate engineering estimates. As an appendix to the novel he documented his calculations. The novel was reportedly awful (and was not published until 2006). But Von Braun used the calculations as the basis for a lecture at the First Symposium on Spaceflight held at the Hayden Planetarium in New York on Columbus Day, 1951. Von Braun's concepts, illustrated by magnificent Chesley Bonestell paintings, were made available to a large public with the publication of a series of articles in Collier's magazine beginning in February 1952. This was subsequently released as a book, 'Across the Space Frontier', in 1953. The technical appendix was published in German as Das Marsprojekt in 1953 and in English in America in 1962 as The Mars Project. Refined designs were presented in 1956 in 'The Exploration of Mars' and reached an audience of 42 million Americans in a series of programs televised on the Walt Disney show. Von Braun's concepts were known to a wider audience than any other of the period. No other series of articles, books, and programs did more to popularize the idea of manned space travel before Sputnik.

Das Marsprojekt was the first technically comprehensive design for a manned expedition to Mars. Von Braun envisioned not a simple preliminary voyage to Mars, but an enormous scientific expedition modeled on the Antarctic model. His Mars expedition was to consist of 70 crew members aboard ten spacecraft - each spacecraft with a mass of 3720 metric tons! To assemble this armada in earth orbit, Von Braun proposed a fully recoverable, reusable three-stage launch vehicle, which was designed to deliver 25 metric tons of cargo plus 14.5 metric tons of 'excess propellant' for the Mars fleet with each launch. Assembly of the expedition would take 950 launches of 46 these reusable space shuttles over eight months from a very busy base at Johnston Island in the Pacific Ocean. The first and second stages would splash down under parachutes 304 and 1459 km downrange, then be towed back to the launch site by a tug. The winged third stage, after dumping its cargo at the assembly point and pumping its excess propellants to the Mars ships, would glide to a landing on Johnston Island. All three stages would be refurbished at the island, stacked, and reused.

The expedition would use minimum-energy Hohmann trajectories to Mars and return, requiring a long stay at Mars, which was certainly appropriate for an expedition of this scale. The expedition fleet would consist of seven passenger ships and three cargo ships, all of the same starting mass. The passenger ships were equipped with 20-m-diameter habitation spheres for ten men per ship, and an extra 356.5 metric tons of propellant for the return trip home. The three unmanned cargo ships would each carry a 200-metric ton winged lander and 195-metric tons of reserve supplies to Mars orbit, and then be left there. There was no thought of automated precursor missions in the days before solid-state electronics. The mission profile was as follows:

- The ten vessels would fire their 200-metric ton-thrust engines for 66 minutes and set course toward Mars. Delta V for the maneuver was 3960 m/s. The calculated ideal figure was 3310 m/s, but the total requirement was greater, allowing for 10% reserves and 3.5% in losses due to the low thrust/weight and long burning time during the maneuver. This burn, at the very beginning of the mission, would consume 2814 metric tons of propellants - 76% of the ship's starting mass. On the other hand Von Braun believed that the tanks themselves, basically pressurized bags of reinforced plastic, could be very light. He estimated that the four tanks jettisoned at the end of the maneuver, including their helium pressurant tanks, would have a mass of only 4 metric tons! Following this maneuver the crews would settle in for the 260 day coast to Mars. Small 3500 kg space boats would shuttle crew members and supplies between the ships of the expedition during the cruise.

- Upon arrival at Mars, the fleet would brake into Mars orbit, entering a circular equatorial orbit 1,000 km over the Martian surface. Delta-V for this maneuver was 2210 m/s, and would require 492 metric tons of propellant. After the burn 2 metric tons of depleted propellant tanks would be jettisoned. The crew would survey the Martian surface from orbit, and pick an appropriate site for the Mars base at the Martian equator.

- One landing boat would separate, deorbit, and glide to a horizontal landing on skis on one of the polar ice caps. It was believed that only the ice caps could certainly provide a flat landing surface (remember that there were no unmanned robot missions to check actual surface conditions before the arrival of the expedition fleet). This was a one-way trip -- the crew had no means of return to Mars orbit. Instead of an ascent stage, the glider's payload was 125 metric tons of pressurized habitat/crawlers.

- The crew of the glider would travel 6500 km in 80 days in their Mars crawlers to the Martian equator, where a base and landing strip were set up. Presumably this was a worst-case scenario - if a suitable landing site nearer the planned base could be found, the first landing boat would be targeted there rather than the ice caps.

- The two remaining landing boats would touch down on wheeled landing gear at the strip. These gliders were equipped with ascent stages that provided the means for return to the expedition's spacecraft in Mars orbit. After the landing, the ascent vehicles would be pivoted upwards, ready to lift-off in case an emergency departure was required. The equatorial orbit of the expedition fleet meant that launch opportunities were available every 2 hours and 26 minutes. 50 of the expedition's 70 crew would be sent to the surface. The other 20 would remain in Mars orbit, keeping the passenger ships in operation and conducting remote surveys of the planet below.

- The reunited expedition members set up inflatable living quarters, and began a 400-day exploration of Mars.

- At the appropriate time, the crew lift-off in the two ascent vehicles and rendezvous with the seven passenger ships in orbit. Transfer of the astronauts and the material they have returned from the surface would be done in free space between the ascent vehicles and the passenger ships.

- Trans-earth injection. Delta-V for this maneuver was 2210 m/s, and would require 222 metric tons of propellant. After the burn 2 metric tons of depleted propellant tanks would be jettisoned.

- 260 days would again be spent on the coast back to earth.

- The seven passenger ships would brake into a 1730 km altitude circular orbit around the earth. Since the vehicle would have a much higher thrust-to-weight now, the burn would take only 163 seconds and the delta-V requirement, absent the losses due to the low acceleration of the departure burn, was 3640 m/s. The crew and their Mars samples would be ferried by their space boats over to shuttles launched from earth or a space station.

Propulsion

For both the launch vehicle and the Mars ships, Von Braun selected nitric acid/hydrazine propellants. These were corrosive and toxic but had the advantage of being storable without refrigeration -- an absolute requirement for the Mars craft, which would spend up to two years in earth orbit during assembly, followed by the three-year trip to Mars and back. Common engines were used in the upper stage of the launch vehicle and the Mars craft. These very conservatively used a combustion chamber pressure of 15 atmospheres (as in the V-2 engine).

Ideal engine performance was based on combustion chemistry and gas dynamics calculations. 'Based on experience', Von Braun expected efficiency losses of 10% for the high-expansion ratio engines. Specific impulse and thrust for the engines was not expressed in common modern terms, which causes some confusion in the literature. The figures given were the specific impulse at the condition of the ambient atmospheric pressure equaling the nozzle exit pressure. The figures adjusted to vacuum specific impulse terms indicate the Mars expedition engines would have a specific impulse of 297 seconds, a very respectable value not achieved in flight for a storable propellant engine until 1962. Von Braun used a constant thrust/weight value of 69:1 in calculating the engine mass for all stages. This again was conservative and in fact would be nearly met on the next US large engine design after the V-2, the Redstone. Von Braun's engine used a separate propellant (hydrogen peroxide) to drive the engine pumps.

Von Braun minimized the scope of the effort, noting that the 5,320,000 metric tons of rocket propellant required for the entire enterprise was only 10% of the amount delivered in the Berlin Airlift and would cost only 4 million dollars. On the other hand, he also noted the many unknowns at the time he was writing. The flux of cosmic rays and meteoroids beyond the earth's surface was completely unknown in 1948. Von Braun recognized the threat of cosmic radiation. But the greater danger of solar radiation was not known. The Van Allen radiation belts, created by the earth's magnetic field which shielded the earth from high energy solar radiation, were not discovered until 1958. So the positioning of the spacecraft assembly at a 1730 km altitude earth orbit, deep in the lower Van Allen belt, would not have been possible. Furthermore, more radiation protection would have to be provided the crew on the journey to Mars and on the Martian surface than Von Braun recognized.

Von Braun did realize that there might be danger of long exposure of humans to zero-G. He suggested that if this was found to be the case, he suggested tethering the passenger ships together, and spinning them with tethers to produce artificial gravity during the coast to Mars and period in Mars orbit. Alternatively, he proposed 'gravity cells', separate dumbbell-shaped spacecraft deployed during the cruise, in which the crew would spend several hours a day under gravity to ensure fitness. It was clear as he thought of his convoy as a community in space, with lots of daily traffic between the spacecraft.

At the time there was no clear technical solution to the problem of interplanetary navigation. Von Braun presumed the crew would take star and planetary sightings during the voyage, calculate their deviation from the planned course, and make appropriate maneuvers. For this purpose a relatively enormous - 10% - propellant reserve was included. This would cover any contingencies, as well as the necessary orbital plane change maneuver required en route and not separately identified by Von Braun.

As contingency against all the unknowns, Von Braun equipped his cargo ships with a 195 metric ton reserve for additional equipment, supplies, and surface probes. This was a huge amount, and certainly enough to build the radiation shelters, gravity cells, and other known dangers.

And finally, like all space visionaries before Mariner 4 in 1965, Von Braun did not know that the Martian atmosphere was only one tenth the density estimated, and that there was not multi-cellular life on the surface, as astronomers were sure they had observed from earth. His graceful long-winged landing boats could not have made a horizontal landing on the surface. But even this was not insurmountable. Von Braun's glider would have had been subsonic at the 47 km altitude of his assumed atmosphere, corresponding to the actual surface pressure of Mars. An alternate landing scenario could have been to jettison the wings just over the surface, deploy a drag chute, and bring the fuselage/ascent stage down to a vertical rocket-powered landing on the surface. Von Braun's design had the margins and flexibility to handle even this worse-case contingency.

Von Braun Mars Expedition - 1952 Mission Summary:

- Summary: First serious design for a manned expedition to Mars

- Propulsion: Nitric acid/Hydrazine

- Braking at Mars: propulsive

- Mission Type: conjunction

- Split or All-Up: all up

- ISRU: no ISRU

- Launch Year: 1965

- Crew: 70

- Mars Surface payload-metric tons: 36

- Outbound time-days: 260

- Mars Stay Time-days: 443

- Return Time-days: 260

- Total Mission Time-days: 963

- Total Payload Required in Low Earth Orbit-metric tons: 37200

- Total Propellant Required-metric tons: 35555.5

- Propellant Fraction: 0.95

- Mass per crew-metric tons: 531

- Launch Vehicle Payload to LEO-metric tons: 39

- Number of Launches Required to Assemble Payload in Low Earth Orbit: 950

- Launch Vehicle: Von Braun 1952

Crew Size: 70.

Family: Mars Expeditions. People: von Braun. Country: USA. Spacecraft: Von Braun Cargo Ship, Von Braun Passenger Ship, Von Braun Landing Boat. Bibliography: 373, 49, 591.

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use