Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Shenzhou - Divine Military Vessel

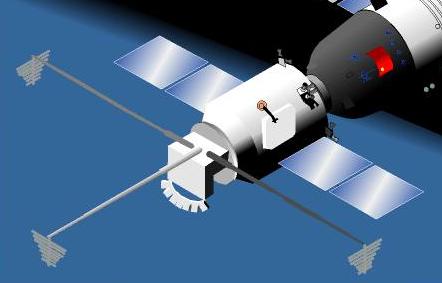

Shenzhou ELINT

Shenzhou with ELINT antennae deployed

Credit: © Mark Wade

The forward, orbital module of the Shenzhou manned spacecraft was designed to accommodate a variety of mission equipment. The orbital module remains in orbit after the service module and re-entry capsule have returned to earth. This means the mission equipment installed correspond in capability to a large unmanned satellite. Shenzhou's two different primary payloads, both of them military, were not discussed by Chinese authorities until early 2003.

Shenzhou 1 and 2 flew with dummy or partial electronic intelligence packages. On those flights three extendible booms were part of an experimental magnetic attitude sensing and control system. Shenzhou 3 and 4 flew with the complete electronic intelligence payload mounted on the nose. As analysed by veteran space-radio expert Sven Grahn, this consisted of two major components. UHF emission direction-finding was accomplished by three earth-pointing television-aerial type antennae deployed on long telescoping booms. These would function in the UHF band between 300 and 1,000 MHz, covering a variety of civilian and military emission sources. They were supplemented by seven horn antennae arranged in an arc. These would detect and localise radar transmissions. This combination would allow coverage of the entire earth below as the orbital module passed over the earth's surface.

Given that China had not previously flown a major ELINT satellite, this was an enormous leap in Chinese military surveillance from space. Each orbital module remains in space as long as eight months after the other modules return to earth. That means the orbital modules of the Shenzhou spacecraft have been scanning the earth 90% of the time, day in and day out, since Shenzhou 3 was launched in March 2002. Data is dumped in ten-minute bursts when the spacecraft pass over Miyun, near Beijing. These missions would have given China's equivalent to the American National Security Agency an excellent introduction into capabilities and problems in flying an operational ELINT satellite over a variety of targets and seasons of the year. The main objective, as was the case for low-altitude Soviet systems, would be to keep track of the US Navy, particularly carrier groups. Observations by Shenzhou 4 during the Iraq War would have been an intelligence windfall for the Chinese.

The second military payload flown aboard Shenzhou is an imaging reconnaissance package. This consisted of two cameras with an aperture of 500 - 600 mm. One is mounted in the equipment package at the nose of the spacecraft, the other below it at what had been earlier thought to be the porthole above the orbital module's main hatch. The use of two differing cameras indicates a hyper-spectral, multi-resolution, combination mapping/close-look system. As reported in Space Daily last March, Zhang Houying of the Chinese Academy of Sciences gave the ground resolution of the close-look CCD camera as 1.6 m.

According to Zhang, the high-resolution imaging payload would first fly on Shenzhou 5. He also reported that Shenzhou 5 would carry a docking system in addition to the camera system. This would seem to be contradictory, since the top camera would have to be mounted over the docking collar.

In any case it may be inferred that the main mission of China's first manned spaceflight will be military imaging reconnaissance. If the pattern of the Shenzhou 3 and 4 flights is followed, the crew will be tasked to identify targets of interest and will fly in a controlled 331 x 337 km orbit for 107 revolutions, or 6.77 days. The orbital module would remain in orbit for up to eight months after the crew returns to earth. Other sources indicate that the manned portion of the flight will be limited to only a single day to minimise risks, after which the orbital module will presumably continue in space on its surveillance mission.

| Shenzhou OM's Shenzhou orbital modules. From left: Shenzhou 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use