Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

L1: The Podsadka Problem

L! Podsadka

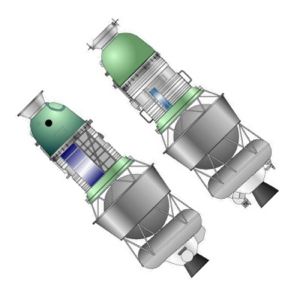

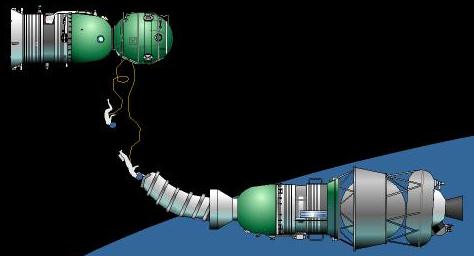

Concept of L1 Podsadka, after the concept of Vick for a curved inflatable airlock and free-space crew transfer.

Credit: © Mark Wade

In 1965 Korolev finally had his N1/L3 moon landing project, but it galled him that his rival, Chelomei, was forging ahead with a completely separate Proton/LK-1 manned circumlunar project. At that time it looked like the Americans would start Apollo flights by 1966, and possibly accomplish a manned lunar orbit mission by 1967. Chelomei's new Proton booster had passed its first tests, but development of his LK-1 manned spacecraft was lagging, especially the development of the re-entry capsule. Korolev had in hand his Soyuz spacecraft, due to start flight test in a few months, The Soyuz re-entry capsule had been designed from the beginning for re-entry from lunar distances. Korolev also had the Block D lunar crasher stage in development for the N1/L3. This was a restartable, liquid oxygen/kerosene stage that was based on both the existing Molniya-L upper stage and several years of design and development work on the cancelled Soyuz B circumlunar stage.

It occurred to Korolev that he could use Chelomei's Proton booster to launch a Block D + Soyuz combination in low earth orbit, then have the Block D rocket the Soyuz toward the moon. From the standpoint of the Soviet state, this would give them a good chance to beat the Americans around the moon, and eliminate duplication in manned spacecraft development. From the standpoint of Korolev, it would allow the re-entry capsule, Block D stage, and translunar navigation, guidance, and communications systems to be tested in advance of the first N1/L3 flights. From a purely personal standpoint, it would allow Korolev to get back at the hated Chelomei and allow him to take control of the entire manned civilian space program.

The devil, as they say, was in the details. At that time Chelomei's UR-500K booster (later dubbed Proton) had a payload mass of 18.5 metric tons into a low-earth orbit. Using a Block D with less-than-full tanks, this would allow a 5 metric ton Soyuz to be launched toward the moon. The problem was this was just not in the cards. The Soyuz was in an advanced stage of development, and the total weight was 6.6 metric tons. For the translunar mission the rendezvous and docking electronics and orbital module could be deleted, but this would still leave the spacecraft at 5.5 metric tons. And the lunar version would require extra mass for thicker heat shielding (at least 300 kg, based on US figures), plus the circumlunar navigation electronics.

Korolev had already got himself deep in trouble with the N1/L3. He had sold the moon-landing project to the leadership as requiring only a single N1 launch when he knew the numbers didn't add up. There was no way to build the lunar orbiter and lunar lander spacecraft within any likely payload the N1 could deliver. Korolev wanted the N1 to be built at any cost - it had been stalled for four years, and the Americans were forging ahead with their Saturn V. He probably had confidence in his abilities to work the problems out in development. Failing that, he probably planned to sell the leadership on a two-launch scenario once he had his booster and spacecraft in hand. Perhaps he felt his mortality, that he had to get something going before he died, before it was too late. In any case, he had been in the Siberian gulag in the death camps of Kolyma -- what else could the regime punish him with if he failed?

It seems almost inexplicable that Korolev had put himself in the same bind regarding payload for the L1 program, but there it was. There were three solutions to the L1 weight problem:

- The safest solution would be to simply use Chelomei's booster to deliver a Block D stage fully fuelled into orbit. The stage would be equipped with the Igla automatic rendezvous and docking system from the Soyuz. A 6.6 metric ton Soyuz could be launched separately on an R-7 based booster. The Soyuz would dock with the Block D, which would rocket the combination toward the moon. This solution had the advantage of good mass margins all around. Its drawback was that there was no way Korolev could sell it to the leadership. Why should they cancel Chelomei's project, which promised to send a man around the moon in a single Proton launch, with a more expensive and complex two-launch solution? Furthermore, this made the whole project reliant on the success of development of the Igla automated system in Soyuz earth-orbit trials. This was far from a sure thing, and would leave the Soviet Union with no means of answering the Americans in the moon race.

- The intermediate solution would be to use a single Proton launch, but to fully fuel the Block D stage. The Proton would not be able to lift the L1/Block D all the way into orbit. A burn of the Block D stage would be needed to put the stack into an earth parking orbit. At the right moment the Block D would fire again and put the L1 on a translunar trajectory. Using this approach, Korolev could get an L1 spacecraft with a total mass of up to 5.5 metric tons -- less than 10% more than the completely unfeasible 5.0 metric ton spacecraft scenario, but (barely) within the realm of possibility.

- A third variant was the 'podsadka' or 'mount-up' approach. This would put the unmanned L1 and Block D into low earth orbit. A separately-launched three-man Soyuz spacecraft would rendezvous with the L1. Two members of the crew would transfer to the L1, which would then continue on toward the moon. This scenario was sold to the leadership as a means of ensuring the crew could get into space if Chelomei's 'unreliable' Proton rocket could not be man-rated in time to beat the Americans. Unspoken was the fact that Korolev could use this alternative in case it proved just impossible to get the mass of the L1 down to accommodate a single-launch possibility. The crew and their spacesuits would represent 200 kg of mass that the Proton would not have to bring to orbit.

The safest solution was not approved, and the both of the alternate 'direct flight' and 'podsadka' variants became the program baseline. The initial estimate, depending on performance parameters of the Proton launch vehicle and Block D stage, were that the L1 spacecraft would have a mass of 5,200 to 5,700 kg when it entered low earth orbit. After entering earth orbit, but before translunar injection, unneeded equipment (for the SAS abort system or podsadka mission) could be jettisoned prior to trans-earth injection. This would leave a spacecraft mass sent towards the moon of 5,000 to 5,550 kg.

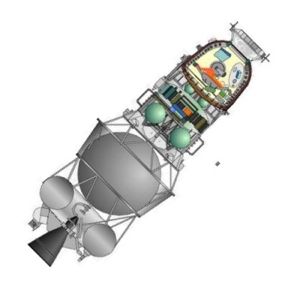

The Cold Equations

The marginal nature of the L1 calculations meant that every kilogram aboard the spacecraft had to be fought over. The spacecraft had to carry additional payload in terms of a thicker heat shield and star sensors and a digital computer for navigation. To save weight in the SA re-entry vehicle, amazingly, the reserve parachute in the re-entry capsule had to be deleted, saving 200 kg. The load of hydrogen peroxide in the orientation thrusters was cut from 40 kg in the standard Soyuz to 30 kg, even though one would expect even more propellant to be used in a lunar return re-entry. In the PAO service module, the hydrogen peroxide thrusters and propellant used for the translation system (required only for docking operations) was deleted. The main propulsion system (consisting of a main engine and two independent back-up engines in Soyuz) was replaced by a lighter single-engine system. The propellant load was cut from 500 kg to 400 kg. Still, with all of the these drastic changes, the L1 could only barely be got under the 5700 kg maximum low earth orbit payload:

| Item | Soyuz 7K-OK | Delta to L1 | L1 |

| BO Living Module | 1,100 | -1,100 | 0 |

| KOS Conical Section | 0 | 180 | 180 |

| SA Re-entry Capsule | 2,810 | 90 | 2,900 |

| of which: | |||

| H2O2 Propellant | 40 | -10 | 30 |

| Heat Shield | 300 | 300 | 600 |

| Reserve Parachute | 200 | -200 | 0 |

| PAO Service Module | 2,650 | -50 | 2,600 |

| of which: | |||

| Avionics/Electrical | 580 | 350 | 930 |

| H2O2 Translation Propellant/Thrusters | 250 | -250 | 0 |

| Engine Assembly | 305 | -50 | 255 |

| Main Engine Propellant | 500 | -100 | 400 |

| Total in Low Earth Orbit | 6,560 | -1,060 | 5,680 |

| TLI Mass | 5,500 |

There was no margin here whatsoever. Even late in the program, the use of 6 kg personal parachutes to give the crew some kind of way of cheating death if the main parachute failed (as on Soyuz 1) was controversial.

In the design mission profile, the L1 plus Block D had a total mass of 22,900 kg after separating from the third stage of the Proton. The SOZ thruster package on the Block D fired briefly to settle the propellants in the stack, then the RD-58 main engine of the Block D fired for 140 seconds to place the whole assembly into a parking orbit (200 km altitude, 51.6 deg inclination). The forward SOK jettisonable support cone was blown off once the spacecraft was in orbit. When the proper moment was reached in parking orbit, the SOZ fired again to settle the propellants in the tanks. Once the RD-58 ignited, the SOZ thruster and propellant tank package separated and was left behind.

The detail of the standard maneuver summary can be reconstructed with good accuracy based on information given in various original documents:

| Maneuver | Starting Mass | Ending Mass | Isp | Burn Time | Delta-V m/s | Comment |

| SOZ DV1 | 22,900 | 22,450 | 250 | 18 | 49 | Block D Ullage |

| Block D DV1 | 22,450 | 19,040 | 349 | 140 | 564 | Place into parking orbit |

| SOZ DV2 | 18,860 | 18,500 | 250 | 15 | 47 | Jettison 180 kg support cone before ignition |

| Block D DV2 | 18,200 | 7,510 | 349 | 439 | 3,028 | Jettison 300 kg SOZ package after ignition |

| L1 Mass | 5,500 | Jettison Block D (1800 kg dry plus residual propellants) |

What made the Podsadka variant possible was that the final mass sent toward the moon was relatively insensitive to any additional mass that was carried into low earth orbit, but jettisoned before translunar injection. The trade-offs were:

- SOK mass: 0 kg = L1 mass 5630 kg

- SOK mass: 180 kg = L1 mass 5575 kg (minimum with SAS electronics as for direct mission)

- SOK mass: 300 kg = L1 mass 5540 kg

- SOK mass: 400 kg = L1 mass 5510 kg

- SOK mass: 430 kg = L1 mass 5500 kg (L1 with two crewmembers)

- SOK mass: 1100 kg = L1 mass 5300 kg

What was the Podsadka transfer mechanism? The most obvious solution would be a female docking collar fitted to the SOK. The crew would transfer from the Soyuz BO orbital cabin to the hatch in the side of the L1 SA capsule. This solution seems to be represented by the L1 drawing at the Kaluga Museum in Russia.

Another solution, for which Charles Vick feels there is clear evidence, would be to fit an inflatable airlock to the SOK. The Soyuz would rendezvous with the L1, but not dock to it. Two cosmonauts would free-float from the Soyuz to the airlock, and then enter the L1 SA through the conventional hatch at the top of the capsule. Some L1 photographs and drawings released seem to show very odd assemblages of equipment in the SOK, not at all like a docking collar or simple SAS electronics.

In favor of the first solution, is the fact that this scenario was being practiced intently by the cosmonauts on the contemporary Soyuz 1-2, 4-5, and 6-7 missions. Why should demonstrating such a docking and EVA be an overriding objective when there was no intention to use it? Furthermore, the same scenario could be used for docking with L1S lunar orbiters launched by N1 (which clearly had no access through the forward hatch since the large lunar orbit maneuvering engine assembly was blocking it).

One objection raised to this scenario is that the SA cabin would have to be depressurized for cosmonauts to enter directly through a side hatch. Russian avionics and electronics were normally placed in a pressurized container in the 1960's. However there are several items of evidence to contradict this:

- Chelomei's competing VA capsule could be depressurized, using controls from the same subcontractor,

- Kamanin's diaries indicate practice by a spacesuited cosmonaut in the SA in getting through the forward hatch to an unpressurised BO aboard the Soyuz. This wouldn't be considered if depressurization of the SA was considered impossible.

- Unmanned L1 Zond 6 actually did partially depressurize due to a failure during its lunar mission. The avionics survived the event for several days of flight. (It was true the capsule was lost due to the parachute release electronics obtaining a static charge build-up in the low pressure cabin -- but Chertok notes that this wouldn't have happened in a pure vacuum. That comment only makes sense if the systems were designed to operate in a vacuum…)

- Soyuz 11 fully depressurized, killing its crew. However the spacecraft's electronics functioned normally through separation from the PAO, re-entry, and landing.

Points in favor of the proposed airlock scenario:

- Use of an inflatable airlock was demonstrated by Voskhod 2 in 1965, at a time when Korolev was surreptitiously considering alternatives to Chelomei's program. The airlock used on that flight makes more sense as a prototype of something being considered for Soyuz / L1 than as a meaningless dead-end.

- The preference displayed in all other Korolev designs (Voskhod, Sever, Soyuz) for an airlock to be provided, keeping one cosmonaut safe in a pressurized cabin to monitor the EVA.

- The argument that the capsule's instruments required pressurization

- Certain other evidence Vick does not want to release yet

A major point contradicting the airlock scenario is that Kamanin, in the tests mentioned above, specifically mentions that the cosmonaut found it virtually impossible to get through the Soyuz forward hatch in a pressurized Yastreb spacesuit.

In any case, it is possible that both solutions were pursued in parallel. Pending any final complete release of information in regard to the Soviet manned lunar programs, the controversy will remain unresolved.

| L1 Podsadka Concept of L1 Podsadka, using Soyuz Igla docking system for crew transfer to hatch in side of L1 capsule. Credit: © Mark Wade |

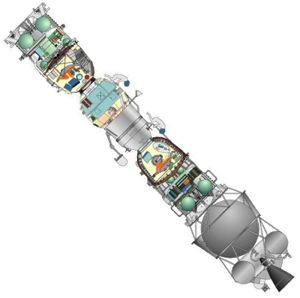

| L1 Cross-section Cross section of L1 spacecraft with Block D stage - after a portrayal in an official RKK History. Credit: © Mark Wade |

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use