Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Chinese Manned Space Program: Behind Closed Doors

Recovery of FSW

Recovery of FSW unmanned reconnaissance satellite capsule.

by E. P. Grondine

Recent press reports indicate that China intends to launch its first man into space by October 1999. Work on a Dynasoar-like manned spaceplane has also been revealed. But these are not news to veteran space reporter E.P. Grondine, who shares this overview of the early Chinese manned space program.

Many space enthusiasts in the United States have watched in frustration for the last twenty years as funding for NASA has declined. They have watched the indecision of Presidents faced with ever tightening budgets, and the constant "downsizing" and "reconfigurations" of NASA administrators as programs are not abandoned but instead forced to fit into those budgets. Supporters of space development have also watched "political engineering" constantly take place as members of the House and the Senate fight to make sure that the remaining space jobs are in their home districts.

Before complaining too much, U.S. space enthusiasts might pause to consider how they would feel if decisions about space were made behind closed doors by the country's leaders. The citizens in such a country could wake up one morning and be told that they now have a space station, which has been successfully launched and is now in orbit. Incredible as it might seem, this is exactly what happened to the citizens of the Soviet Union in April of 1971.

A similar event happened in China in March 1995. The people of China were told that China would launch a manned capsule into orbit by the year 2002. They were told that their government had entered into a contract with Russia for the purchase of the technology for escape systems, heat shields, and docking systems that would be necessary for the manned spaceship, and that the government intended to pay the Russians for them with hard currency and consumer items such as radios, televisions, stereo systems, and other electronic goods.

While this is similar to what happened in the old Soviet Union, the situation in China today is not quite as bad as that. While the leaders of China have decided that attempting to set up democratic institutions in a country with a population 4 times as large as that of the United States, one fifth the agricultural land, and which has been devastated by several hundred years of civil war and political upheaval, would only lead to chaos, nonetheless they have begun to conduct debates about how the country is to be run. While these debates are no longer restricted just to the top leaders, but now include hundreds of specialists, the general public is told little about them except that they are taking place. Among the topics debated in recent years was China's future space program, including its manned program, and the only way that anyone outside the debate (including western observers) could guess what was going on was to combine information from many sources, taking a sentence here and a sentence there from different articles, adding them together with off hand reports, official statements, and contract negotiations with Russia, shaking them altogether, and reasoning out an estimate of the Chinese program.

EARLY FAILURE?

The first Chinese and Russian announcements were met with scepticism by western analysts. They had heard statements many times before by the Chinese that they intended to launch a man into space, and these statements had always come to nothing.

The first time the analysts had heard these statements was back in the late 1970's. In February, 1978 an article in the Chinese technical journal Navigation Knowledge first publicly announced that the Chinese were working on the technology necessary for manned spaceflight. In November of that year Jen Hsin-Min, the head of the Chinese Space Agency, confirmed to Dr. Edward Ezell, a western analyst, that China was indeed not only working on a manned space capsule but on a space station as well.

The United States was curious as to what was going on, and in 1979 arranged for a NASA team to visit the Chinese facilities in order to explore the possibilities of co-operation in space exploration. Jen Hsi-Min confirmed to the NASA team that China was working on not only a manned capsule but also on a "Skylab" as well, and the NASA team was shown everything but the manned space development centre itself.

In January, 1980 Chinese journalist Xiao Yong reported in the journal Science Life about a visit with the Chinese astronaut trainees at the Chinese manned spaceflight training centre. Xiao described the trainees' physical training and described them getting into their spacesuits for pressure tests. It would not be until 1988 that the Chinese would admit that the Space Flight Medical Research Centre for the cosmonauts had been under development since 1968 under the direction of the founder of the Chinese rocket program, the famed scientist Qian Xuesheng, (Tsien Hsue-shen) who had fled from Cal Tech and the United States during the McCarthy era.

According to a recent report in Renmin Ribao by reporters Jia Yurong and Guo, in May, 1980 the newly constructed Chinese recovery fleet retrieved their first capsule from the South Pacific. The capsule launched on 18 May, 1980 was observed by the Australians and reported by them to have been a warhead, but the new report shows that it was designed as a recoverable capsule.

The Chinese had launched recoverable capsules in 1974, 1975, 1976 and 1978, but the capsule that the recovery fleet was sent to pick up in May, 1980 was not a member of this series of satellites, known as the Recoverable Test Satellites or Fanhui Shi Weixing, which were recovered on land. The first of a second generation of unmanned recoverable spacecraft would be launched two years later in 1982, but these spacecraft would be similar in design to the first series of Recoverable Test Satellites and not of a new design.

In December, 1980 Wang Zhuanshan, the Secretary General of the New China Space Research Society and Chief Engineer of the Space Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, announced that while the launch and recovery of astronauts was no longer a problem, manned flight was being postponed because of its cost and the lack of a pressing need to have it.

Immediately thereafter, and in direct contradiction to this, in January, 1981 the Chinese released photos of the astronaut trainees training at the centre and a sketch of the manned rocket. The rocket is similar in size to the US's Mercury/Redstone, and while the drawing is crude, the rocket is most likely a member of the Feng Bao family of launch vehicles produced in Shanghai. The payload may be clearly identified as being manned because the capsule is equipped with an escape tower, a piece of equipment not necessary for unmanned flight.

For several years following there were no further reports from China on manned space flight.

WHAT HAPPENED?

All of Chinese society had been rocked by the chaos of Mao's Cultural Revolution and the struggles for leadership following Mao's death, and despite Chou Enlai's attempts to protect it, the Chinese rocket industry had been hurt as well. The effects of this chaos had showed up in repeated launch failures of Chinese rockets. There have been rumours in the west that the Chinese lost their first cosmonaut, and given the large number of failures that the Chinese civilian booster the Feng Bao ("Strong Wind" or "Storm") had, it seems increasingly likely that these rumours may be true. To my knowledge to this day the identities and the ultimate fates of the astronaut trainees shown in the Chinese publications remain unknown.

CHINA'S NEXT ATTEMPT

Talk of manned space flight died down for a while, and even a diplomatic initiative in 1984 by President Reagan to fly a Chinese cosmonaut on the U.S. shuttle went nowhere. In September, 1986 the Peoples' Daily reported that China was selecting a team of astronauts who were starting training, but at the same time there were statements made that manned spaceflight was still too expensive.

This state of affairs lasted until 1990, when Wang Shuanglin, Deputy Chief of the United States Division of the China's Department of American and Oceanic Affairs, told western participants at a conference that China was studying the development of a four man capsule to be launched by China's Long March 2-E Rocket. A paper to the International Astronautical Federation in 1992 by the scientist Xiandong Bao of the Electromechanical Equipment Research Institute of the Shanghai Astronautics Bureau set out what the studies ultimately led to.

Xiandong's paper gave a detailed description for a new rocket which used liquid oxygen and kerosene for its fuels, instead of the hypergolic nitrogen tetroxide and un-symmetrical dimethyl hydrazine traditionally used by China for its rocket fleet. The Shanghai Astronautics Bureau set out a proposal similar to one that Japanese scientists have only recently discussed for their H-2, a proposal for clustering together a number of the basic rockets to form a rocket capable of placing very heavy payloads into orbit. They also proposed a liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen fuelled stage which could be used as an upper stage for the rocket, increasing its payload even further.

In addition to describing this rocket, Xiandong discussed adopting the new rocket for manned spaceflight, and in doing so he showed China's then current design for a manned spacecraft. Xiandong's diagram clearly showed a manned capsule which the Shanghai Astronautics Bureau had designed for use with an improved versions of China's Long March commercial launcher, and this could be determined by examining the proposed spacecraft's diameter and mass.

In April, 1992, by the time of Xiandong's paper's appearance, the leaders of China's State Science and Technology Commission announced their intention to develop manned spacecraft by the year 2000, as well as a space station, and a "state of the art space-Earth transportation system" by the year 2020. They also opened the Space Flight Medical Program Research Centre to the press.

In August, 1992 China successfully flew Recoverable Test Satellite Number 13. In a report by the official Chinese news agency Xinhua the satellite was identified as being of a new design and it was stated that it had "major significance for expediting China's scientific exploration and technological experimentation, as well as for developing the technology of carrying people into space".

In October, 1993 the Shanghai Astronautics Bureau shipped their whole design proposal to Beijing for the country's leaders to consider as they drew up the science and technology program for inclusion in the Eight and Ninth Five Year Economic Plans. Shanghai proposed to the leadership the development of six large carrier rockets and eight new spacecraft, including a manned one, as part of the Eighth and Ninth Five Year Plans. Things looked good for manned space flight going into the planning sessions.

ANOTHER FAILURE?

In October, 1993, at the same time that the Shanghai Astronautics Bureau submitted their proposal to the leadership, the Chinese had a failure with Recoverable Test Satellite Number 15. The return capsule was misaligned when its de-orbiting rocket engines were fired, and instead of de-orbiting the satellite, their burn placed it into an even higher orbit.

This event would mean little by itself, but the payload of the satellite was somewhat unusual, as it included 1,000 numbered stamps, 3,000 first day covers, credit cards, photos, 194 telephone calling cards (which are coveted by Japanese collectors), and 235 "personal items" such as precious ornaments and a diamond studded Mao pin.

THE DECISIONS

The Shanghai Astronautics Bureau's proposal was carefully evaluated by the Chinese leadership, and while it is not known exactly how they arrived at their decisions, some factors which influenced them are known. First of these were the economic factors. In order to discourage China from pursuing sales of rockets as weapons, as well as to encourage the development of the peaceful use of space by China, the United States had allowed the export to China of satellites built in the United States for launch on Chinese rockets. By the time of the considerations for the Eighth and Ninth Five Year Plans nearly thirty launches of the existing Long March Rockets had already been sold. There was no indication that commercial satellites would get any heavier, and instead there was every indication that a large part of the communications satellite market would be taken over by networks of small satellites in low Earth orbit.

The development of a new, more powerful rocket must not have seemed to the Chinese leaders to be justified on economic grounds, but they did decide to develop the capability to manufacture geosynchronous communications satellites completely independently of the United States, and thus to free their commercial launch industry from dependence on U.S. policy concerns.

Second, just as in the United States, Europe, and Russia, in China the technologies used for space launch vehicles are the same technologies used to build intercontinental rockets for the delivery of nuclear explosives. Just as in the United States, Europe, and Russia, the Chinese companies that manufacture rockets for the launch of civilian payloads into space are the same ones that develop and manufacture military rockets. The Chinese military had already had under development more powerful rockets with longer range than those currently existing, and while the Shanghai Astronautic Bureau's rockets' liquid oxygen and kerosene fuels would give them a greater commercial payload and be less polluting, the poisonous nitrogen tetroxide and un-symmetrical dimethyl hydrazine fuels of the current Chinese military and civilian rockets can be stored in the rocket's own fuel tanks at room temperature. This makes it possible to launch them instantly, and this ability to launch a rocket instantly before an enemy can destroy it makes the requirement for instant launch an essential military requirement. The program for the large liquid oxygen and kerosene rockets was delayed, and resources were put instead into the development of large solid motors for military use. More encouragingly, the Chinese have also recently shown liquid strap on boosters for the Long March series of launch vehicles. These strap on boosters will not only allow these rockets to launch a manned capsule, but they have an advantage for manned flight in that unlike solid boosters they can be shut down should an emergency arise.

Third were the political factors. Because of the government of China's inability to develop China's democratic processes, the leaders of the western democracies have limited their countries' contacts with China. Even if the leaders of China decided to develop a manned spaceflight capability, they knew they might face being snubbed by the countries involved in the International Space Station.

This problem led to efforts on two fronts. While China announced that the primary focus of its space program was going to be the development of communication satellites, work on the development of the liquid boosters for the Long March family of launch vehicles began, and construction was started in the north-east suburbs of Beijing on a new flight control centre capable of handling manned spacecraft.

A NEW DESIGN

In September, 1994 Chinese President Jiang Zemin visited the Russian Flight Control Centre in Kaliningrad, where Space Station Mir is controlled, and he spoke with the cosmonauts onboard Mir. Jiang noted that there were broad prospects for co-operation between the two countries in space, and later he paid a visit to Yekaterinburg, where other Russian space manufacturers are located. Much hard bargaining undoubtedly followed, but the deal with the Russians in March, 1995 made it clear that the leaders of China had decided to pursue manned space flight.

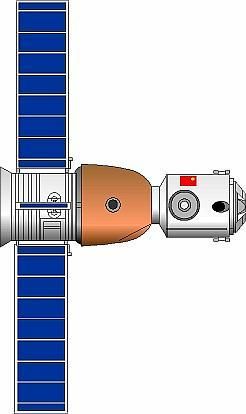

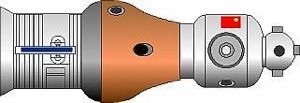

Since that time western analysts have shown drawings for Chinese manned spacecraft that differ markedly from that of the Shanghai Astronautics Bureau, and these illustrations show an adaptation of the manned spacecraft which was developed in the Soviet Union with the intention of launching it onboard the Zenith rocket, which Soviet scientists had also planned to use as a booster for their Energia heavy lift launcher.

The date the Chinese government now announced for manned space flight, 2002, was the same year that had been announced by NASA for the completion of the International Space Station. It appears that viewing the chaos in Russia, the leaders of the government of China may have decided that they would not be able to reform their political process in time for participation in the ISS, and that therefore they would develop their own independent manned space program as a matter of national pride.

A SPACE STATION?

As for a space station, it is possible that the Chinese may acquire from Russia technologies for a space station, just as they are now acquiring the advanced weapons systems developed by the former Soviet Union. A vacuum chamber with a diameter of 7 meters and a height of 12 meters has already been built, and perhaps with the help of the Russians by the time the International Space Station is put into orbit, we will see the Chinese orbit a space station of their own.

A CHINESE SHUTTLE?

Addendum: by Mark Wade and E P Grondine

China has only recently announced work on an indigenous ‘space shuttle', and some photographs have been released of a wind tunnel model and computer simulations of airflow around a delta winged spacecraft. The narrow fuselage and wingtip vertical stabilizers are strongly reminiscent of the United States' X-20 Dynasoar spaceplane of the 1960's.

China published photographs of a two-seat trainer as early as 1980. This was possibly a test cockpit in an aircraft that flew parabolic trajectories to provide brief periods of zero-G. Given Qian Xuesheng's lifelong interest in winged hypersonics, it seems likely that this two seater was indeed the cockpit for a Chinese Dynasoar-type spaceplane. Reports long ago reported the existence of a wind tunnel model and such reports have continued through the years.

The shuttle's layout seems to be based on the US X-20 Dynasoar of the 1960's (rather than the similar Myasishchev VKA-23 Design 2 concept which Chinese scientists may have had unsanctioned access to in the Soviet Union during the late 1950's). Perhaps the design was derived from US drawings which were declassified after Dynasoar was cancelled.

Some reports indicate that a manned shuttle, rather than the Project 921 ballistic spacecraft, will fly before the beginning of the next millennium. Although unlikely, only time will tell which report is correct.

| Chinese Spacesuit Chinese astronaut in spacesuit being prepared for test in altitude chamber, 1980. |

| Chinese Seat Chinese astronaut in spacesuit and high-G spacecraft seat, ca. 1980. |

| Chinese Space Food Chinese astronaut trainees sample space food, ca. 1980. |

| Chinese Astronaut Chinese astronaut in pressure chamber spacesuit test, 1980. |

| Chinese Manned Craft Chinese manned capsule, according to 1992 published drawing. Oddly-shaped re-entry vehicle, very small orbital module forward with orientation thruster package in the nose. |

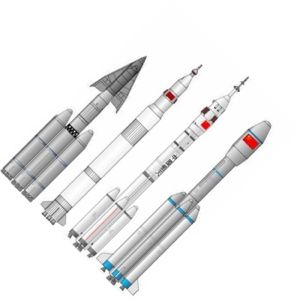

| CZ-2E |

| CZ-2E(A) Booster CZ-2E(A) launch vehicle that will be used for manned missions. |

| Chinese Spaceplane Chinese spaceplane in re-entry attitude. Dynasoar-like configuration based on published photo of wind-tunnel model. |

| Chinese Shuttle Photo published in 1980 of Chinese astronauts training in a shuttle-type cockpit. |

| Chinese Spaceplane Chinese spaceplane on CZ-2E launch vehicle. |

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use